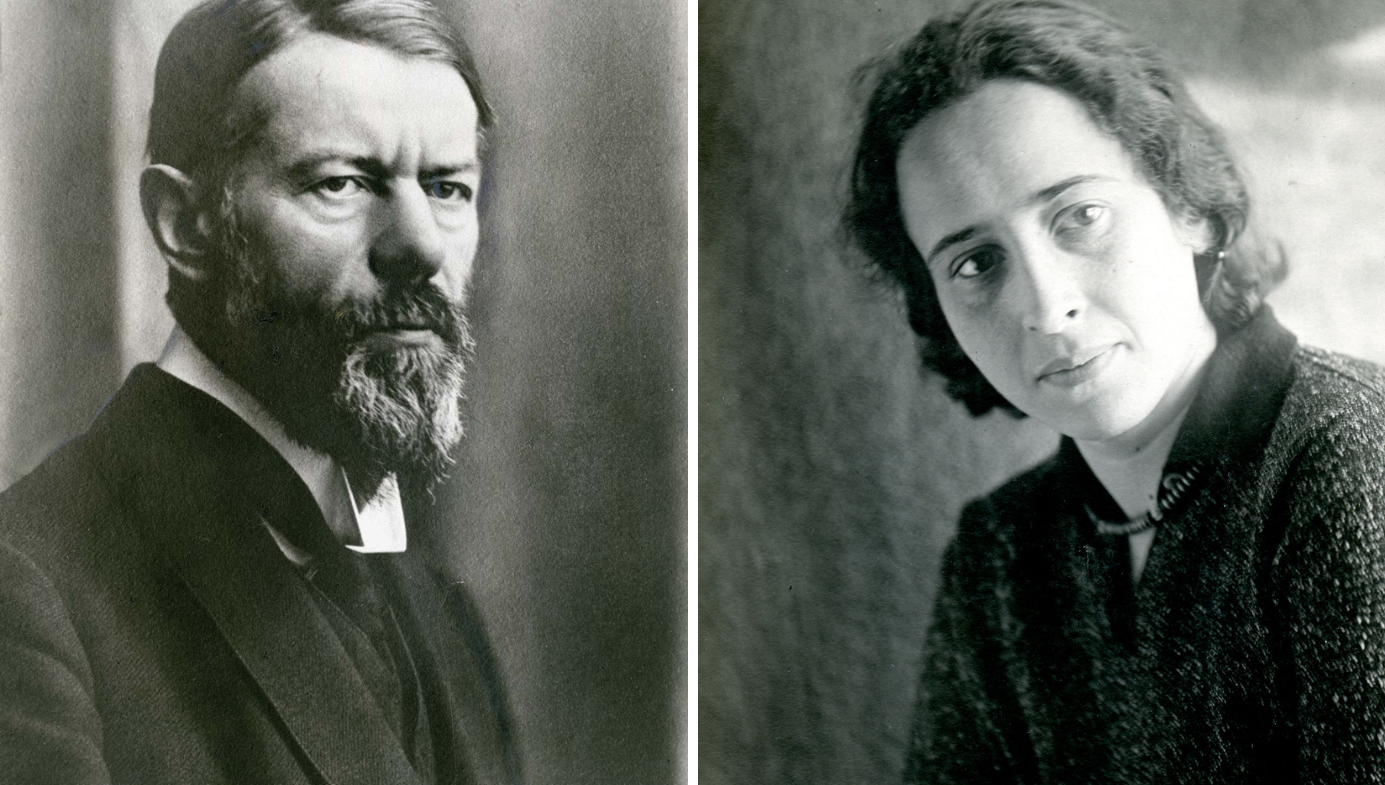

Hannah Arendt

Lessons from Hannah Arendt on Arresting Our ‘Flight From Reality’

Fascism, communism, and transhumanism all lure us into rejecting the real human condition in favor of ideological constructs.

In 1949, when Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) went to Germany as part of the New York-based Jewish Cultural Reconstruction Commission, she was struck by the way the Germans showed an “at times vicious refusal to face and come to terms with what really happened.” This “escape from reality,” as Arendt named it, meant that the reality of the Holocaust and the death factories was spoken of as a hypothetical. And when the truth of the Holocaust was admitted, it was diminished: “The Germans did only what others are capable of doing.”

The Germans, at times, simply denied the facts of what had happened. One woman told Arendt that the “Russians had begun the war with an attack on Danzig.” What Arendt encountered was a “kind of gentleman’s agreement by which everyone has a right to his ignorance under the pretext that everyone has a right to his opinion.” The underlying assumption for such a right is the “tacit assumption that opinions really do not matter.” Opinions are just that, mere opinions. And facts, once they are reduced to opinions, also don’t matter. Taken together, this led to a “flight from reality.”

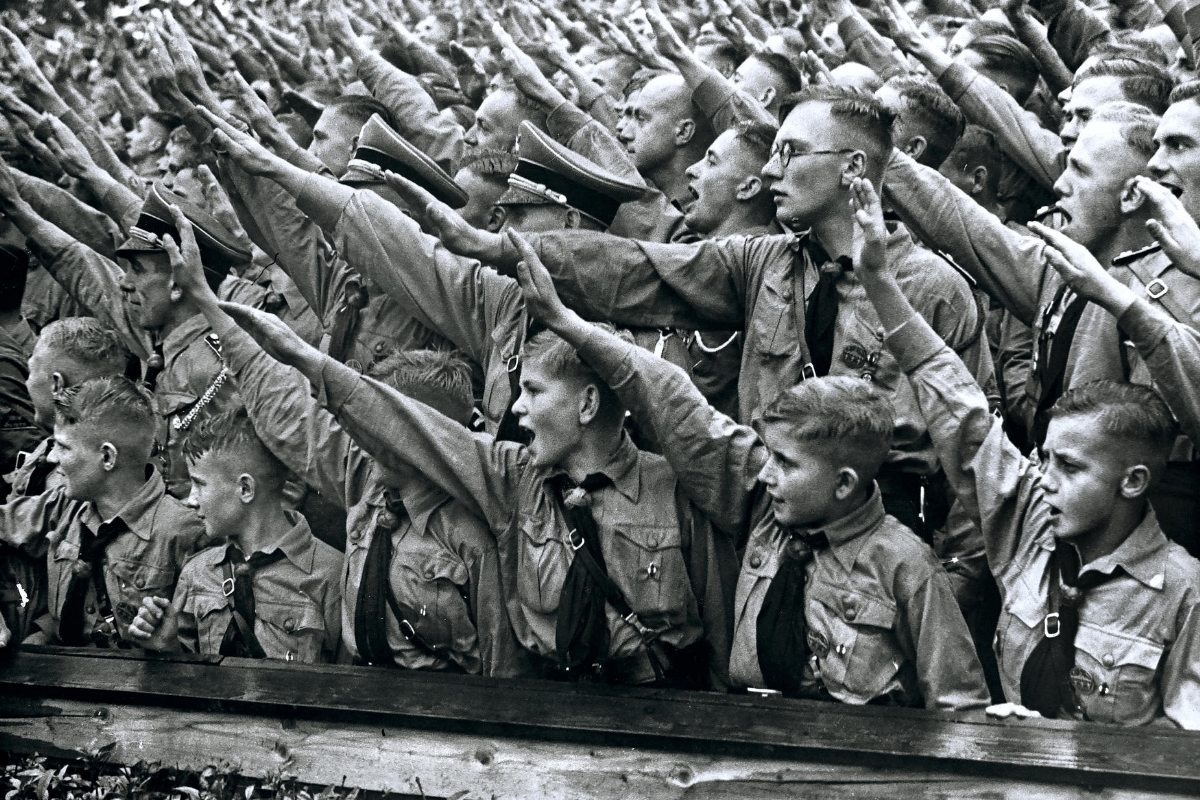

The focus of Arendt’s lifelong engagement with the human flight from reality was her encounter with ideologies, specifically Nazism and Bolshevism. In The Origins of Totalitarianism and other texts (especially her essay, On the Nature of Totalitarianism), Arendt defines an ideology as a system that seeks to explain “all the mysteries of life and the world” according to one idea. Nazism is an ideology that blames economic disaster, political loss, and the evils of modernity on the Jews—inhuman flotsam who must be exterminated to allow a master race to flourish. Bolshevism, on the other hand, “pretends that all history is a struggle of classes, that the proletariat is bound by eternal laws to win this struggle, that a classless society will then come about, and that the state, finally, will wither away.” The bourgeoisie are not simply class traitors, they are a dying class, and killing them only supports a law of history. As ideologies, both Nazism and Bolshevism insist on explaining the events of the world according to theories “without further concurrence with actual experience.” The result, Arendt argues, is that such ideologies bring about an “arrogant emancipation from reality.”

Because an ideology “looks upon all factuality as fabricated,” it “no longer knows any reliable criterion for distinguishing truth from falsehood.” As reality recedes, ideologies organize society to transform their ideas into living reality. If antisemitism as an ideology says that all Jews are beggars without passports, the fact of wealthy and established Jews must be eliminated. If Bolshevism says that the bourgeoisie are corrupt, they must admit their corruption or be killed. The realization of such ideological realities can be accomplished, of course, through terror.

But even before a totalitarian movement takes power and mobilizes the secret police in the machinery of terror, ideological movements can employ propaganda to deny and nullify facts, or change them. The Nazis, she writes, “did not so much believe in the truth of racism as desire to change the world into a race reality.” Similarly, the Bolshevist ideology that classes were dying was not something real, but something that had to be made real. The purges and terror that Stalin unleashed were supposed to “establish a classless society” by exterminating all social groups that might develop into classes. In both instances, the purpose of the ideology was to transform a mere opinion—race consciousness or class consciousness—into the “the lived content of reality.”

The point, as Arendt concludes, is that “ideological consistency reducing everything to one all-dominating factor is always in conflict with the inconsistency of the world, on the one hand, and the unpredictability of human actions, on the other.” What ideology demands is that man—an unpredictable and spontaneous being—cease to exist as such, that all humans be subjected to laws of development that follow ideological truth. That is why the turn from an unreliable reality to coherent fantasy requires an absolute elimination of human spontaneity and freedom.

What distinguishes the modern lie from the long history of human mendacity is its capacity to deny and replace reality. The modern lie is ideological in that it rejects all contrary evidence and all inconvenient facts. It involves, as Arendt writes, the “mass manipulation of fact and opinion” toward the totalizing end of “rewriting history” and the present to fit one idea. Traditional lies sought to hide the truth; the modern lie “deals efficiently with things that are not secrets at all but are known to practically everybody.” It seeks to deny facts that are obvious and present and replace them with an alternate image that, though obviously unreal, is accepted as real because it is seen and felt to be more true and more palatable.

The modern lie can succeed because, when faced with the anarchy, loneliness, and senselessness of modern life, “the masses probably will always choose” the consistent and logical certainty of an ideology. The choice of a coherent fiction over the messiness of reality is “not because they are stupid or wicked, but because in the general disaster, this escape grants them a minimum of self-respect.”

The burgeoning field of research into “motivated reasoning” confirms that the desire to find meaning in membership in a group will lead adherents to hold onto the tenets of a collective ideology, even in the face of clear factual evidence to the contrary. Human thinking, as Arendt argues, is concerned not with truth, but with meaning, which Arendt holds to be the basic human need. That is why, for Arendt, the most fundamental of human rights is the right to have rights, the right to speak and act in a political world so that one is meaningful. But being part of a group, a people, a nation, or even a political party is often more humanly significant than the truth. We are all motivated to believe facts selectively in line with our political and social needs.

The root of our susceptibility to the modern lie is the rise of what Arendt calls mass loneliness. While loneliness is not a new phenomenon, it has transformed itself in the modern age. Throughout human history, Arendt observes, loneliness was a “borderline experience usually suffered in certain marginal social conditions like old age.” But it has now “become an everyday experience of the ever-growing masses of our century.”

Loneliness has become a mass phenomenon with a metaphysical dimension. Increasingly, people feel adrift amidst the purposeless of life, amidst the death of God, and amidst the break in tradition. “The Foundational experience on which terror rests as the essence of totalitarian domination and ideological-logical thinking as the principal of its action is abandonment” (in German, verlassenheit).

Modern loneliness begins in the shattering of collective dreams and common hope. Hope gives life purpose and shape. In this sense, hope is a story that one sees oneself within. It can be the story of religious salvation or the story of a family tradition. It can be a national story or the story of a clan or tribe. Or it can be a cosmopolitan story in which one imagines oneself a part of a world community. It is this hopeful story that is the breath of life. The loss of hope is like the loss of dreams—an abandonment that sets the foundation for the rise of the modern lie that rejects reality and invents a new and more palatable world.

If the human capacity for inventing fictional worlds turns man against reality, so, too, does the drive to invent ever newer and more powerful technologies that alter our world and even ourselves. The rise of automation, the yearning for intelligent machines, the ability to create life in a test tube, and the desire to augment human potential through artificial intelligence all promise to free humanity from the real limitations that have till now been part of the human condition. We humans are mortal; we are fallible; and we are prone to exhaustion and irrational outbursts. Technology offers a path beyond our weaknesses and the potential of an alternate reality, one in which we merge with machines and artificial enhancements to cure us of human deficiencies.

The promise of modern science addresses an ever-present-but-only-now-realizable drive to make life and man artificial; to cut, as Arendt put it, “the last tie through which even man belongs among the children of nature.” We will soon “produce superior human beings.” We will be able “to alter [their] size, shape and function.” The desire and the imminent possibility of making life itself artificial is indicative of a profound “wish to escape the human condition”—one expressed in the “hope to extend man’s life-span far beyond the hundred-year limit”:

This Future man, whom the scientists tell us they will produce in no more than a hundred years, seems to be possessed by a rebellion against human existence as it has been given, a free gift from nowhere (secularly speaking), which he wishes to exchange, as it were, for something he has made himself.

Human existence, at least as it was for thousands of years, is not something humans make or control. Unlike the artificial worlds we create, we ourselves are a free gift. In a religious register, that gift can come from God. In a secular world, the free gift of human existence is a matter of fate, chance, or fortuna. In religious or secular terms, however, the human condition is one of finitude and mortality. It is this aspect of our humanity that science threatens, insofar as science internalizes a way of thinking that yearns to fully master all elements of the earth, including humans themselves.

The earth, then, is Arendt’s name for that one aspect of man’s reality—his mortal finitude—that must remain if man is to remain subject to the traditionally conceived human condition. While humans may cultivate crops and domesticate animals, while we may build dams and form polities, we cannot shed our mortal coil. To be alive, man, just as animals and plants, must be born and he must die—an organic and natural process that must remain free from the artifice and fabrication that humans bring to all other aspects of earthly existence.

And so our ideological flight from reality is simultaneously met by our desire to master that reality through technological means—with both of these forces causing a rejection of reality’s power. The tree in the forest, and with it the real world, dissolves “into subjective mental processes.” Common sense retreats, and the commonality we experience—what we all share by being part of a real world common to all—comes to be replaced by our “faculty of reasoning.” Arendt calls this “the playing of the mind with itself, which comes to pass when the mind is shut off from all reality, and ‘senses’ only itself.”

A political choice is presented: Are we so alienated from the world in which we have lived that we are willing to remake it—ourselves included—to conform to perfectionist desires?

There may be nothing more terrifying to the human mind than reality, what Nietzsche called the stone of the past. The past is the one thing that human invention can’t change. It is a reality that the will cannot master. When the past is horrific or simply oppressive, it stands against us and over us.

In the face of the past, Nietzsche counsels reconciliation with what is. What is best, the Nietzschean prophet figure Zarathustra says, is that one love even what he most despises. To unlearn the spirit of revenge—the gnashing of teeth at the “it was” of the past—is to learn “reconciliation with time and something higher than reconciliation.” For Nietzsche, the love of what is requires us to “see as beautiful what is necessary in things,” and thus to elevate the natural to the beautiful. Where loving affirmation of what is real remains impossible—when one is not yet strong enough to be merciful to oneself or to others—then one should pass by.

Following Nietzsche, Arendt understands reconciliation and “passing by” to be closely connected. As she writes, “in reconciliation or passing by, what another has done is made into what is fated to me, that which I can either accept or that I can, as with everything that is sent to me, move out of its way.” Faced with a wrong or an unwelcome reality, Arendt suggests that we have the choice of either reconciliation—affirming one’s acceptance of the existence of a world that includes such a wrong—or at least passing by—silently allowing the wrong to exist. In either case, the judgment is made that reconciles oneself to the existence of the wrong and persistence of the wrongdoer.

But a third choice is available as well: namely, in the face of that irreconcilable reality, to deny reconciliation. “Reconciliation has a merciless boundary, which forgiveness and revenge don’t recognize—namely, at that about which one must say: This ought not to have happened.”

Arendt explains what she means by reference to Kant’s discussion of the rules of war, wherein Kant says that actions in war that might make a subsequent peace impossible are not permitted. Such acts, whether in war or peace, are examples of “radical evil”; they are “what ought not to have come to pass.” Such acts are also those that cannot be reconciled, “what cannot be accepted under any circumstances as our fate.” Nor can one simply silently pass by in the face of radical evil. Thus, Arendt’s judgment to accept a fateful wrong will differ meaningfully from Nietzsche’s fatalism. For both, reconciliation with what is—wrong or right—is to be affirmed or accepted. For Arendt, however, there is a limit to reconciliation that Nietzsche does not seem to recognize.

For Arendt, reconciliation is a political act of solidarity with the existence of others. When I decide to reconcile with the world as it is, I affirm my love for the world, and thus my solidarity with the world and those who live in it. In this sense, reconciliation is the precondition for the being of a polis: It is the judgment that, in spite of our plurality and differences, we share a common world. To reconcile with a wrong is to affirm one’s solidarity with the world as it is—and is, therefore, to help bring into being a common world. Arendt thus turns to reconciliation as “a new concept of solidarity.”

Arendt’s most famous example of a judgment of reconciliation is her judgment not to reconcile with Adolf Eichmann. Faced with an epic wrong and a wrongdoer who refuses to repent, reconciliation would affirm a world in which something like the Holocaust could happen. Reconciliation, therefore, would be powerless to remake the human community shattered by the Holocaust. For Arendt, reconciliation with Eichmann is impossible.

When Arendt turns to reconciliation, her touchstone is Hegel: “The task of the mind is to understand what happened, and this understanding, according to Hegel, is man’s way of reconciling himself with reality; its actual end is to be at peace with the world.” In Truth and Politics, Arendt raises the problem of a thoughtful reconciliation to reality alongside a reference to Hegel: “Who says what is always tells a story. To the extent that the teller of factual truth is also a storyteller, he brings about that ‘reconciliation with reality,’ which Hegel, the philosopher of history par excellence, understood as the ultimate goal of all philosophical thought.” Reconciliation, she writes in The Life of the Mind, affirms that “the course of history would no longer be haphazard and the realm of human affairs no longer devoid of meaning.” There is a basic truth to Hegel’s idealism: that the real world is for humans only insofar as we humans understand that world and reconcile ourselves to it.

Hegel’s view of reconciliation is, however, in need of revision. He argues that reconciliation allows us to make peace with the world as it is. But peace may not be the adequate response to the world, Arendt writes: “The trouble is that if the mind is unable to bring peace and to induce reconciliation, it finds itself immediately engaged in its own kind of warfare.” Arendt questions whether reconciliation and the peace it would bring are possible. Against Hegel, she asks: What happens when reconciliation fails?

In asking after reconciliation, Arendt is raising the problem of how to approach reality when amidst the “break in tradition” and the “death of God.” The Marxian response—to force reality into a new progressive reason guided by science—goes down the path of totalitarianism. Instead, Arendt councils a new idea of reconciliation: reconciliation to a world without political truths, one in which politics is closer to a kind of unwinnable warfare—one specifically suited to the human mind.

Against “Hegel’s gigantic enterprise to reconcile spirit with reality,” Arendt reimagines reconciliation as a facing up to the basic fact of the modern world. We must reconcile ourselves to the fact that there is no truth in politics, and all politics is a struggle among opposing opinions. This does not mean there are no political facts, or that truth is politically irrelevant, but there are fewer political facts than most people think. Further, such facts as there may be are themselves cemented only by persuasion and opinion. They are settled political facts that come, by weight of overwhelming persuasiveness, to be part of the shared common world. We must reconcile ourselves, she argues, to a world of plurality absent authority and absent all but the most foundational truths.

Arendt’s rethinking of reconciliation follows her conviction that sometime in the early part of the 20th century, philosophy and thinking ceased to be able “to perform the task assigned to it by Hegel and the philosophy of history, that is, to understand and grasp conceptually historical reality and the events that made the modern world what it is.” A gap emerges between reality and thinking. This gap between thinking and reality is not new, and it is even “coeval with the existence of man on earth.” But for centuries and millennia, the gap was bridged over by tradition. Reconciliation demands that we forgo the will to absolute knowledge or scientific mastery of the world. We must instead reconcile ourselves to the reality of the gap between thinking and acting. We must, in other words, reconcile ourselves to our irreconcilability to the world.

Adapted, with permission, from The Perils of Invention: Lying, Technology, and the Human Condition, edited by Roger Berkowitz, published by Black Rose Books, Copyright @ 2022.