Comedy

Dave Chappelle vs. the New Puritans

As the legendary comedian chalks up prestigious awards and plays to packed houses, his progressive critics look increasingly ridiculous.

On July 20th, First Avenue, a venue that describes itself as “the epicentre of music and entertainment in Minneapolis,” broke its booking contract with Dave Chappelle, one of America’s most popular stand-up comics. As noted in First Avenue’s own promotional materials, Chappelle is “the 2019 recipient of the prestigious Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, has earned more than 30 nominations and awards in television and film … has received five Emmy awards [and] has won the Grammy Award for Best Comedy Album three years in a row, 2018 through 2020.” Indeed, First Avenue itself gave Chappelle a star on its Wall of Fame in 2013. But as Chappelle’s performance date approached, none of that was enough to save him from the mob.

Trans-rights activists have had Chappelle in their cross-hairs for several years now—most recently alleging that he made transphobic jokes in his massively popular Netflix special, The Closer (which, to add insult to injury, has earned Chappelle yet another Emmy nomination). And First Avenue felt their wrath. A mighty handful signed a petition demanding the show’s cancellation, claiming that “Dave Chappelle has a record of being dangerous to trans people, and First Avenue has a duty to protect the community. Chappelle’s actions uphold a violent heteronormative culture and directly violate First Avenue’s code of conduct.” This—along with a few upset staff who reportedly threatened to call in sick—led First Avenue to cancel the show and apologize to its critics thusly:

To staff, artists, and our community, we hear you and we are sorry. We know we must hold ourselves to the highest standards, and we know we let you down. We are not just a black box with people in it, and we understand that First Ave is not just a room, but meaningful beyond our walls. The First Avenue team and you have worked hard to make our venues the safest spaces in the country, and we will continue with that mission. We believe in diverse voices and the freedom of artistic expression, but in honoring that, we lost sight of the impact this would have.

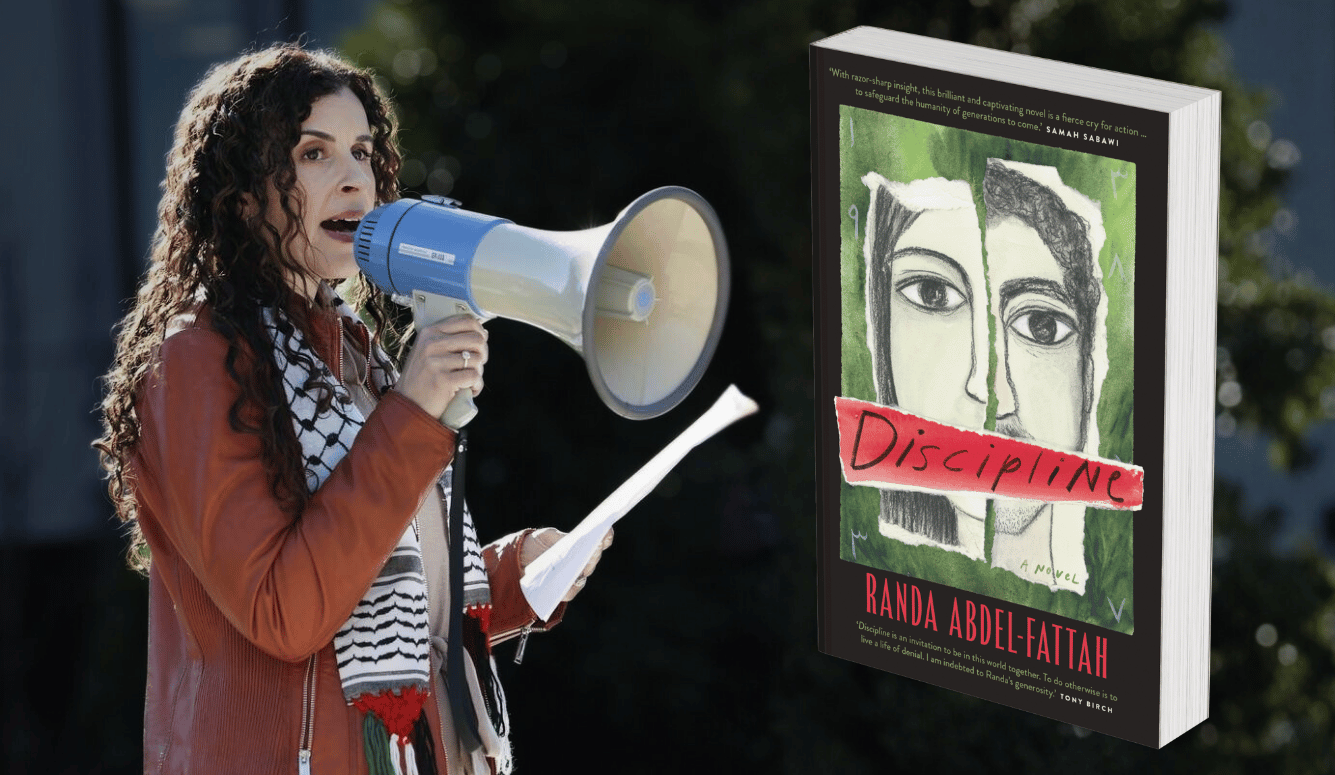

Fortunately, paid up fans were able to redeem their tickets at the nearby Varsity Theater, which had already booked Chappelle for two shows later in the week, and simply added an extra performance. The full house at the Varsity was met by a few dozen protesters with bullhorns, and one of the patrons was hit with an egg. But all that the activist campaign really accomplished was to heave one more garbage bag onto the public-relations dumpster fire currently burning up mainstream support for leftist social causes.

To whom was First Avenue referring with the words “our community”? Evidently, not the crowds of Minneapolis theatre goers that packed Chappelle’s three performances. Rather, I suspect, the term was meant to describe the self-appointed ideological enforcers among the theatre’s own staff, along with their in-group friends within local art and activism subcultures. That’s a rather tiny and insular “community” for a theatre to cater to, especially by comparison to the mass audience served by any real “epicentre of music and entertainment.”

We hear you. Tonight’s show has been cancelled at First Avenue and is moving to the Varsity Theater. See our full statement for more. pic.twitter.com/tkf7rz0cc7

— First Avenue (@FirstAvenue) July 20, 2022

How does honouring diverse voices and freedom of artistic expression create a negative “impact” on anyone? How had First Avenue lowered its “standards” by booking a multiple Grammy and Emmy winner? How would Chappelle’s show have compromised First Avenue’s reputation for safety? And in what way is the venue “meaningful beyond our walls”—a phrase that suggests a priestly mission, or, at the very least, a position of exalted moral leadership (as opposed, to, say, the Varsity, which one presumes to be a refuge for unfeeling heretics)?

For years now, many comedians have been turning down college shows, whose organizers increasingly require performers to explicitly disavow material that might be denounced as offensive. First Avenue’s treatment of Chappelle now raises similar concerns about major music venues. What first-tier act will book a space that cancels shows at the last minute, for nakedly ideological reasons, and then throws in public character assassination (dressed up as apology) for good measure? What agents and managers will contract with theatre operators whose signatures mean nothing, and who’ve now shown themselves ready to buckle in the face of complaints from a few of their own ushers and bartenders?

As anyone who’s followed this sort of cancel-culture drama might have predicted, First Avenue’s act of self-flagellation did little to calm the sort of aggrieved activists who demanded the cancellation of Chappelle’s show—since being aggrieved tends to be their preferred state. Consider this follow-up report in a local media outlet:

Ian Sutherland says their feelings about their employer’s actions haven’t changed since the show got canceled. Sutherland is queer and trans and has worked as a sound engineer and stage manager at First Avenue for three years. Their band Birth Order made an Instagram post Tuesday condemning the decision to host Chappelle, along with musicians Psalm One, New Primals, Gully Boys, Serious Machine and others. ‘Nothing’s been fixed. Nothing feels better,’ Sutherland said Wednesday afternoon.

Needless to say, Sutherland wants First Avenue to engage in what a reporter described as “a meaningful conversation with staff.” Another employee said First Avenue’s “corporate upper management thinks they can get away with a lot and ride off of performative action … If this is the kind of priority that safety takes in their minds, we don’t need them unless they change.” No doubt, much garment rending will be on display during any such “conversations.” But what further substantive “change” could these umbraged souls possibly be demanding now that they’ve proven their de facto veto power over bookings?

Beyond the implications for First Avenue itself, the incident underlines the progressive Left’s boundless capacity for self-sabotage. As has been noted elsewhere in Quillette, Chappelle himself is pretty much a card-carrying believer in the doctrine of intersectional oppression, offering clear dissent only on the narrow issue of gender. And even when it comes to this one topic, he isn’t really a transphobe at all, but rather a humane LGBT “ally” who’s spoken out in the past against anti-trans bathroom bills.

How can the progressive movement remain viable as a mainstream political creed if it’s so brittle as to require the demonization of a true believer over a single ideological deviation? One cannot help but be reminded of the hysteria over “deviationism” that tore apart communist cadres a century ago.

Those who go after left-wing gender dissidents such as Chappelle, Ricky Gervais, and JK Rowling tend to disavow any desire to curtail free speech, claiming that they are merely imposing proper “consequences,” holding wrongdoers to “account,” and protecting the “safety” of this or that community. These euphemisms disguise the same basic authoritarian impulse that, until relatively recently, was associated with the reactionary Right.

Most famously, this impulse took expression in US Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee in the 1950s. But it also contaminated the world of comedy, as with the cancellation of the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in the 1960s following complaints from aggrieved members of the religious and political Right, and the blacklisting of comedy legends such as Lenny Bruce on the basis that their foul language might “harm” the wider community.

Strictly speaking, it is absolutely true that mob attacks on Dave Chappelle don’t constitute censorship, a word that indicates the suppression or prohibition of expression by force of law. But this is a dangerous hair for progressives to split. After all, the argument that a private business has the right to shun customers or suppliers at its pleasure is the same one used by conservative printers who refuse to publish LGBT flyers, and bakeries that refuse to provide cakes for gay weddings.

Nor can the activists seeking to shut down Chappelle justify their position on the basis that he’s a bully who “punches down.” All of us in the worlds of L, G, B, and T were vilified once upon a time, and continue to be harassed in certain milieus. But this is far from true in the culture at large, where our civil rights have been secure for years, and where we’ve been fully included in contemporary political and social elites. The trans community includes stars such as Laverne Cox, Eliot Page, and Eddie Izzard who are widely celebrated in popular media. Government forms now ask for gender rather than sex. Corporations push employees to put pronouns in their email signatures. Schools teach that gender non-conforming children may be trans. Hospitals are redefining “maternity wards” and “mothers” as “birthing centres” and “birthing parents,” so as to include the 0.007 percent of babies delivered by trans men. (The number I cite is based on data from Australia, where self-described transgender men accounted for 22 of the country’s 305,832 births in 2019.) Meanwhile, venerable LGBT organizations are telling lesbians that it’s transphobic to refuse “lady dick”; and us gays are told to develop a taste for men’s vaginas. As part of this erasure of sex-based attraction, the Vancouver Pride Society has just blocked the participation of lesbians who refuse to define “woman” as anyone who claims to be one.

Vancouver Pride Society has refused entry to the Pride Parade to lesbians who have a sex-based definition of woman. We refuse this attack on our #sexbasedrights. Check out our campaign https://t.co/EfpajXCpCw #proudtobealesbian #vanpride2022 #bcpoli #sexmatterstolesbians pic.twitter.com/hjYeSmWyYG

— Vancouver Lesbian Collective (@VanLesbians) July 30, 2022

No activist group with that kind of power can claim to be marginalized. Indeed, the demonstrated ability of a handful of Minneapolis stage and service workers to cancel a performance by one of the greatest stand-up comics of all time makes the opposite case: In contemporary, mainstream society, those who challenge trans orthodoxy are punching up.

This isn’t me conjuring arguments on Chappelle’s behalf. He’s made this case explicitly, casting himself as a black underdog, and coding LGBT community activist elites as white. As he says in The Closer, “I’ve never had a problem with transgender people. My problem is with white people.” Or again, “You think I hate gay people and what you’re really seeing is that I’m jealous of gay people. I’m jealous, and I’m not the only black person that feels this way … Gay people are minorities, until they need to be white again.”

I should caution here that this is hardly a uniform position within the black community, as black critics such as Kenyon Farrow and Saeed Jones have noted. (And for what it’s worth, I’ve offered my own critique of Chappelle’s reductionist racial take on LGBT activism here.) But incidents such as the woke tantrum at First Avenue, and the (extremely white) anti-Chappelle protests at Netflix in 2021, should give serious pause to progressives. In these fights, they are centering white woke gender saviours trying to silence a ground-breaking black cultural hero—a particularly bad look in Minneapolis of all places, it being ground zero for the racial-justice protests that rocked the world in 2020.

Not so long ago, Chappelle was a cutting-edge darling of the Left, thanks to his authentically transgressive comedy (which included characters such as black crack addict Tyrone Biggums). He wrote a sendup of ’50s-era family sitcoms called The N*ggars, and walked away from a $50 million contract with Comedy Central out of concern that his white progressive audience was laughing for the wrong reasons. And the woke critics who’ve suddenly turned on Chappelle now that he’s refused to take their ideological marching orders seem to have justified his suspicions about white fandom. As Chappelle said when asked about the trans activists protesting outside the Varsity, “I’d respect them more if there was at least one black person.”

Last year, Chappelle’s former high school, The Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington, DC, announced that it would name a new theatre after its most famous graduate (who is also a generous benefactor). But the naming was postponed for reasons that, at this point, I shouldn’t really need to explain. And when the renaming finally went ahead this year, Chappelle stunned everyone by withdrawing his name from consideration and instead asking that the facility be called the Theatre for Artistic Freedom and Expression.

Chappelle got his wish, cleverly turning what some hoped would be a humiliating act of cancellation into a demonstration of his own commitment to principle. As in Minneapolis, it was a spectacle that invited onlookers to weigh the appeal of a funny, sharp-witted, charismatic social critic versus that of a humorless mob that demands universal adherence to a program of rigid ideological conformity. The culture war around Chappelle isn’t over, and may keep raging on for years. But it isn’t hard to predict which side will eventually have the last laugh.