Arts and Culture

Lost Soul Behind Bars

The untold story of Upheaval, a prison band that recorded one of the most sought-after soul singles of the 1970s.

To most people, the words “Paradise Lost” will conjure repressed memories of 10th grade English and compulsory subjection to literary poetry. Only a very select few will know that it is also the title of one of the most sought-after 45s in existence—a five-and-a-half-minute horn-laden soul epic. It is said that only 25 copies of this percussive masterpiece were ever pressed. The musicians who composed, performed, and recorded it 50 years ago called themselves “Upheaval,” and they were all inmates at the Waupun Correctional Institution (WCI) in Wisconsin, a maximum-security facility then known as the Wisconsin State Prison. Their origins have never been documented until now. This is their story.

I. The Teacher

The common denominator behind Upheaval was Dave Bultman, although if asked, he would likely downplay his contribution. Bultman left his teaching job at a nearby high school in Oshkosh to become director of the WCI’s music program in June of 1973. In his memoir, Crowbar Tech, he recalls that he saw an advertisement for the position in the local paper and figured if he wasn’t cut out for it he could always return to the classroom. Back then, the music options available to inmates were dismal—a fire in January 1971 had reduced resources and space to a corner of the gymnasium. The prison had lacked a music director for nearly a year, and Bultman’s predecessor reportedly had a fairly narrow preference for marching band music. Through a combination of insurance money collected after the fire and some reshuffling of taxpayer dollars, the WCI built a new music facility with numerous soundproofed practice rooms and a variety of quality instruments, including a Fender Rhodes piano and a Gibson ES-335 guitar.

Bultman required prisoners to write about what they’d learned from his music theory class if they wished to remain in his course and have access to instruments. Given his academic background, he was not especially interested in wasting time defusing aggression or babysitting idle minds; he wanted to teach composition and arrangement because he knew that inmates who sought studio work on the outside would need to be musically literate. The members of Upheaval took this requirement a step further, demanding that all band members be able to play at least one instrument, vocalists included.

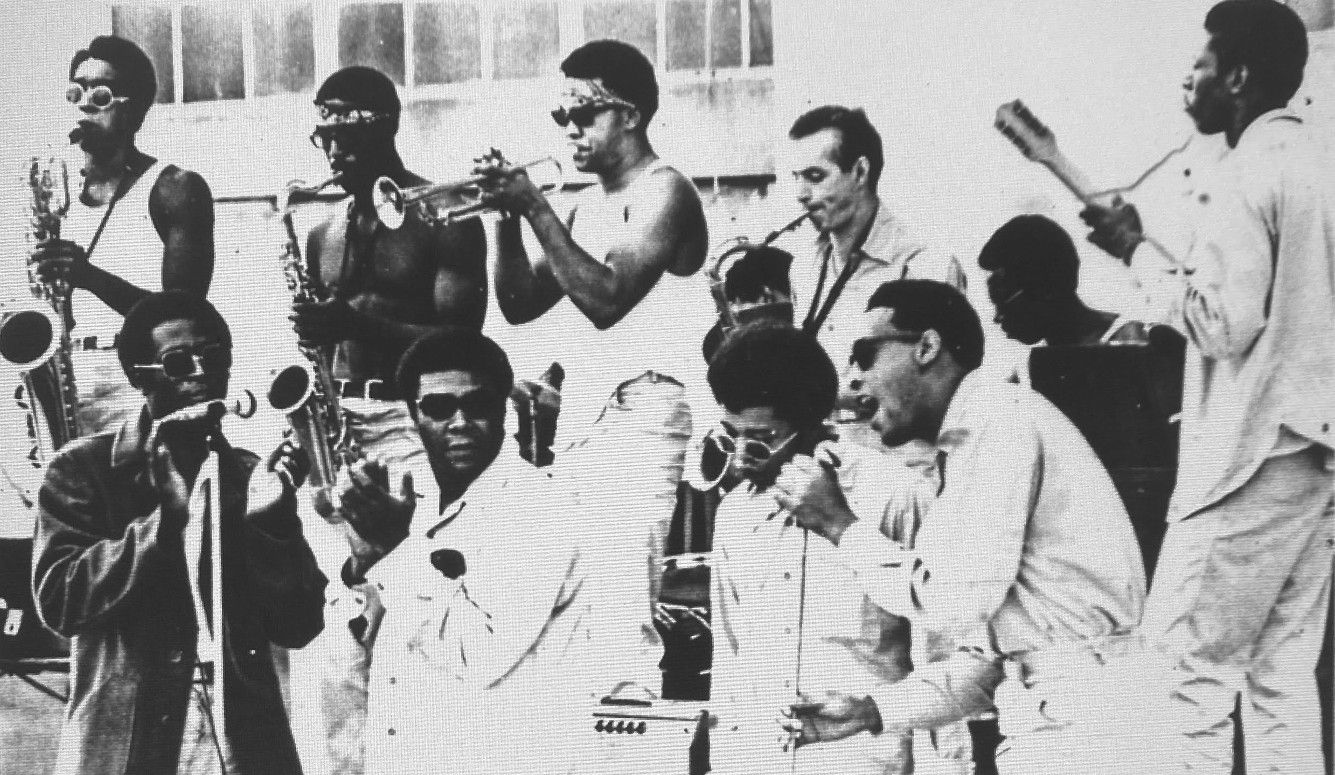

Eventually, Bultman was managing 100 students a day, and outsourcing some of the teaching to the more accomplished inmates while he helped others rehearse. Their competence ranged from crude ability to those who, in Bultman’s estimation, could “compete with the best professionals.” His pride is palpable in a 1974 interview he gave to the Madison-based Capital Times, “These guys are good. They sound like something.” Increased demand for the course meant that prisoners were soon required to take musical aptitude tests, and if they passed, they would have to wait for a spot to open. They painted the walls of the music facility with psychedelic colors and patterns, chords, and portraits of jazz greats, transforming it into the most inviting part of the entire prison. The wide variety of ethnicities and heritages represented at the WCI was reflected in the diversity of sounds. In additional to Upheaval’s nine-piece soul band, which regularly headlined inmate concerts (referred to as “banquets”), there were also blues trios, jazz quartets, Latin ensembles, rock bands, and country & western groups.

Teaching in a maximum-security prison was not without its challenges. In 1975, an inmate named Leon Irby drove a welding rod through his attacker’s eye and into his brain, purportedly to defend himself from an attempted rape. For this he pled guilty to second-degree murder and part of his sentence included six months of solitary confinement. Before being sent to “The Greenhouse” (the WCI name for solitary confinement due to the unit’s verdant paint job), he begged Bultman to teach him the piano. Since inmates were not allowed to have musical instruments in solitary, Bultman drew two-dimensional diagrams of keyboards, supplemented with finger positions, assignments, and music theory books. Six months later, Irby was able to apply what he learned on a real piano. “It took him a while for his fingers to adjust from the flat surface of the sheets of paper he used before to the three dimensional form of the piano in front of him,” Bultman recalls. “We were both amazed when he started playing arpeggios up and down the keyboard.” The educational experiment was short-lived, however. Irby was quickly transferred to a different prison after his release from solitary to protect him from retribution.

Similar disciplinary issues plagued Upheaval and made it hard to keep a regular band in rotation. Joe Hayes, now 75 years old and the last known surviving member of Upheaval, tells me that they “would not even consider any guys that were not doing hard time”—if you were going to be transferred or paroled in a year or two, the return on investment to train and rehearse with them was simply not worth it. Indeed, the criminal records listed on Upheaval members’ prisoner security cards include charges such as armed robbery, sale of heroin, attempted murder, and first-degree murder.

On the other hand, membership of the band incentivized inmates to stay out of trouble while incarcerated, so they would have more time to play, sing, and create together. The studio served as a sanctuary where they would practice eight hours a day, Monday to Friday. Mutual protection became a byproduct of the amount of time the men spent together. Despite the huge demand for access to the music rooms’ limited space and instruments, Bultman guarded Upheaval’s ability to practice more than any other group, and this protection was reciprocated. “Bultman knew we had his back,” Hayes recalls. “Nobody would fuck with him.”

The success of the music program even led to Bultman being offered the job of main warden, a career move he declined because his music gig “was too gratifying to give up.” The satisfaction he got from working with people who wanted to be there made all the difference. The band certainly benefitted from his lessons on technique and chord structure. “The discipline required to practice and make progress was built into their minds,” he said, “because competition among inmates is far greater on the inside than for musicians on the outside. If you can’t hold up and prove yourself, trouble is going to come your way.”

In time, the WCI music program progressed to the point that, according to a report in the Milwaukee Sentinel, prison officials decided “the inmates deserve an audience and the public deserve to hear them.” A small Upheaval concert was held on February 21st, 1974. The following Monday, one of the journalists lucky enough to attend that performance for the Sheboygan Press reported, “The two one hour shows drew a standing ovation.” A subsequent experiment—the first of its kind—invited 200 outsiders for a concert within the prison walls, featuring Upheaval and other acts. Between performances, a drummer headed for the bathroom. Since this was a male-only prison, only one male or female was allowed to use the bathroom at a time during the show. The drummer entered the bathroom, found the disguise he had hidden there, and then walked out wearing a skirt, a blouse, a padded bra, women’s shoes, a wig, and make-up.

When the concert ended, the guard monitoring the door didn’t notice the transformation, nor did the staff at the security checkpoint. The only sign that something was amiss before the nightly cell block tally came up a man short was that the drum kit had not been packed away. The escapee was recaptured a year later and returned to the WCI, but this episode led to an indefinite suspension of invitational concerts. Upheaval, however, continued to reign as the de facto “house band” at the Waupun Correctional Institution, headlining shows for their fellow inmates. These were often followed by a separate set just for the prison staff, and some Upheaval members performed double duty in other bands. Depending on which source you lean on, Upheaval’s repertoire of original material included between 100 and 1,000 songs (Hayes’s boastful recollection being the latter).

II. The Music

Given the sheer volume of material Upheaval is said to have produced, only a handful of songs survive in recorded form in varying degrees of audio quality. In addition to the song that prompted this essay, ‘Paradise Lost,’ Hayes has a CD’s worth of Upheaval recordings, including the funky lo-fi offering ‘Come On with the Come On,’ and the irresistibly groovy ‘Vampire Lady,’ a lament (or perhaps a warning) about an exsanguinating relationship. The chorus goes:

You’re more dangerous than sun is to Dracula,

Every time I hear your name,

Blood runs cold in my veins.

But I always (always) come back to you.

Here I come, Vampire Lady.

Only a fraction of Upheaval material was ever recorded, and listening to those remaining recordings, one feels like a paleontologist carefully brushing the sediment from a dinosaur fossil—the experience yields a rarely preserved set of clues from which to extrapolate a larger understanding of the whole. Perhaps the greatest find of all is about an hour’s worth of video shot in 1975 of a prison rehearsal that the Wisconsin Historical Society unearthed and digitized from half-inch tape. Until its discovery, this footage had remained unseen for nearly 50 years. It demonstrates that the group’s range of material spanned the R&B spectrum from sweet soul to uncompromisingly rough funk, but it also hints at what the music meant to Upheaval’s members in a way the audio alone does not. A subtle nod between players, a wry smile, the microphone control, and the overall technical proficiency are all signs of the band’s confidence and professionalism as a musical unit.

‘Broken Down Porch’ is a slow and sensual soul ballad, written by James Harris and infused with an unshackled sense of freedom replete with vocal harmonies. ‘Ready Train’ is a powerhouse that begins with a call-and-response between snare brush and flute, before gradually increasing the tempo until it gathers the momentum of a steam locomotive. The title recalls Curtis Mayfield’s ‘People Get Ready,’ but Upheaval’s ‘Ready Train’ is less concerned with pleas for racial equity than it is with the sonic propulsion of its relentless conga drumming. It continues to pick up steam as the funky chank of the rhythm guitar feeds the groove, and layered harmonies cry “all aboard!” as Upheaval’s conductor of soul guitar licks, James Lampkins, punches your ticket.

One of Joe Hayes’s personal favorites is the song ‘Happy Hooker.’ It’s exceptionally well written and arranged, and he claims it was originally composed for the 1975 film of the same name about the former Dutch madam and call girl Xaviera Hollander. When the film’s producers refused to pay Upheaval for the song, he tells me, the band copyrighted ‘Happy Hooker’ thereby preventing its use in the final cut.

To write much more about individual songs is difficult because words fail to adequately capture the experience of hearing them. There is a certain ineffability in Upheaval’s sound that, like any great music, defies description. Eddie Quinn, one of Upheaval’s key songwriters, published a short essay in the January 1971 edition of the monthly prison newspaper Waupun World, articulating his definition of soul music for the uninitiated. He wrote:

Soul music is for real. It is raw, angry and mind riveting. It is music to encompass the total Black experience—the field holler, the Baptist shout, the sanctified church, the segregated schools, the hunger and the injustice, the ghetto and the joys and trials of love. This does not exclude white people, though. But if whites are really to be included, they must emerge with a new kind of humility. Some have already done just that. White ‘Blue Eyed’ soul can be heard on almost all radio stations day and night. … Soul has emerged as a dominating part of tomorrow’s pop music. It is essentially the music of a specific time and place. That time is now; the place is America. To listen to soul music hard is to know something about man’s struggle for freedom. So, when you think of soul, soul music, and soul brothers, think of them as interpreters of a conscious people. It is a sense of total music that extends outward to the listeners like an irresistable [sic] magnetic field. At its best, soul is a mysterious and almost spiritual happening that occurs when the musicians are in tune with themselves and their listeners.

III. The Players

As Eddie Quinn pointed out, soul music did originate from a uniquely black experience. When rioting swept the United States after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, black-owned businesses in some areas survived looting and property destruction by spray-painting the words “SOUL BROTHER” on their windows. For Quinn and the vast majority of the Upheaval’s members, their shared experience was of being young incarcerated black Americans during the 1960s and ’70s: their music evoked the freedom of a people, as well as the individual, and this defined their sound, as well as their relationships to one another.

Joe Hayes, who was one of the original members and vocalists (in addition to playing trombone, trumpet, and saxophone), says the foundations for Upheaval were laid in 1963 at the Green Bay Correctional Institution, a separate prison about 80 miles north of the WCI. It was here that Hayes met and formed a vocal group with LaVelle Rudd, Charles May, and James Lampkins. Like many soul singers, Hayes grew up singing in church—the Reformation Church of Christ in Milwaukee—from the age of five. It was not until their incarceration that most of Upheaval’s members learned to play instruments. Perhaps the most astounding example of this was Lampkins, who can be seen in the one of only two surviving Upheaval film recordings from 1975 playing the vibraphone on ‘Happy Hooker’ and the concluding guitar solo in ‘Ready Train.’

Hayes told me that Lampkins was a natural, quickly picking up on music theory and composition. Despite his musical precocity, after his eventual release from prison, Lampkins died homeless in Milwaukee. Tragically, this would be a common theme among other band members. There would have been no Upheaval without imprisonment, which allowed them to train and rehearse for years together, but their incarceration would also prove to be their curse. Finding a steady job and keeping a roof over their heads following release was nearly impossible for many of them due to their criminal histories.

Hayes tells me how much he wanted to continue to sing after he left prison: “I had a God-given talent, I wanted to use it. I just wish I could’ve taken it further.” He says that, after his release, he met with Smokey Robinson who invited him to sing at Motown, but Hayes’s parole officer refused to let him cross state lines and the opportunity slipped away. While incarcerated, Upheaval’s continued dominance of the prison banquets garnered enough attention for their performances to be recorded live on television and local radio. Hayes says these broadcasts even reached the ears of James Brown, who was apparently so impressed that he wanted Upheaval to be his opening act. What might have been their breakthrough fell apart because two band members were serving life sentences (both would be released many years later).

Eddie “Baby Q” Quinn would find his way into the group after his transfer to the WCI, establishing himself as a songwriter and leader. He also contributed several “Music Scene” op-eds to the monthly edition of Waupun World. Upheaval’s progenitor was a band called QCR—the initials of Eddie Quinn, Charles May, and LaVelle Rudd—for which Quinn and Rudd wrote most of the material. Other soul bands in the prison at the time included Yusef & The Fellows, King Thomas and the Blue Flames (a likely nod to James Brown and the Famous Flames), a gospel group called The Spiritual Five, and The Sudanese, which featured Willie “Sheik” Gray who sang professionally in the Milwaukee area prior to his incarceration. Gray was a later addition to Upheaval, his lead singing is captured on film in ‘Happy Hooker,’ and he could also double as a backup vocalist. Although Gray was later released from the WCI, he died trying to rescue his wife from a burning house when the building collapsed on top of them both.

During our interview, Joe Hayes absorbed the Upheaval footage with a critical eye and ear. He pointed out the familiar faces of Lampkins, Gray, and Hayes’s good friend and keyboardist, James “Weed” Harris (Harris is credited with guitar and vocals on the 45). Harris and Gray had crossed paths prior to their incarceration in grade school. Hayes’s eyes lit up the moment he recognized early Upheaval songs, and sang along with the harmonies, head tilted upwards, eyes closed. (He also made sure to inform me that the vocals on ‘Happy Hooker’ didn’t sound right and weren’t as good as they were when he was in the group.)

The filmed footage coincided with Hayes’s replacement by James Turner, a broad-chested and powerful presence who can be seen and heard as the lead vocalist on ‘Love Station.’ At Bultman’s suggestion, Turner gave up cigarettes so that his vocal range could improve. His motivation bolstered by the positive changes in his voice, he continued to increase his breathing capacity by running laps of the track in the prison yard. Upheaval secured a fairly regular work release, earning small stipends for their weekend performances outside the prison around the state of Wisconsin for the public. On more than one occasion, Hayes recalled that Turner snuck backstage and attempted to flee during set breaks—behavior that did not sit well with the remainder of the band, who saw their work release program as a welcome change of scenery and an opportunity to make some money.

The percussionist credited on ‘Paradise Lost,’ Melvin Torrence, is featured in the archival footage on congas. A couple of taped fingers indicate how much he practiced, and there is some evidence that he remained in Upheaval at least through August 1976. He hand-wrote an excited letter to the Office of Human Development in Chicago, and another following his release in 1977, offering to send them an Upheaval videotape for review in the hope that their music would yield some financial recompense. He said they had arranged at least a dozen more songs, but unfortunately no record remains of their existence. Eddie Quinn called Ernie Warren, the drummer credited on the Upheaval 45, “among the greatest I’ve heard in the state. He’s as good as Vic Pitts of the Cheaters or Stonewall of the Seven Sounds.”

James Preston was one of the few Upheaval members to arrive at the WCI already able to play an instrument. A horn player of exceptional talent, Bultman’s prison memoir devotes half a chapter to him. Bultman would listen to a CD of Preston’s “Jazz Tune in C” on nearly every long road trip he made, and even went as far as copyrighting the song in the Library of Congress. Bultman sent copies of the song to local radio stations, but to his knowledge, it was never played. Preston claimed to have learned the saxophone with Sonny Rollins when he did time at Rikers Island. Although Rikers does not have records with which to confirm booking dates, Preston’s Waupun security card confirms he was born in 1923, and arrived at the WCI in 1963. Public records show that Rollins served 10 months at Rikers in 1950, and again in 1952 after being arrested for violating the terms of his parole—so, the dates are plausible.

In his “Music Scene” op-eds in Waupun World, Quinn explains what it was like to work with LaVelle Rudd, one of the founding members of Upheaval. A frequent songwriter, Rudd was also a bassist, vocalist, and cowriter of ‘Paradise Lost.’ “LaVelle Rudd is a singer’s singer,” Quinn wrote. “There’s very little he can’t sing. He ranges from low bass to high tenor or fifth with ease. ’Velle has been crooning for years. I’ve had the pleasure of singing with him, off and on, for about nine years. He has an ear for music which makes him a capable arranger.” In addition to his leadership role in Upheaval, Rudd also had a talent for prose. He took over the Waupun World associated editor position in May 1971, and had his own regular column called “LaVelle Raps,” in which he wrote about topics as varied as respecting women, remaining hopeful while incarcerated, and his philosophy of rehabilitation. In one piece, Rudd quipped, “A major decision that each man must make is whether he is going to make his time serve him or allow his bitterness, in whatever form, to cause him to sink deeper into the mire of his own inabilities.”

LaVelle’s daughter, Hedi Rudd, was kind enough to share some of her father’s romantic poetry. Later in life, he struggled with health issues. A nasty case of Raynaud’s resulted in gangrenous sores that required the amputation of his fingers, robbing him of the ability to play bass guitar. As painful as that loss was, he was finally able to secure a home after going on disability. This home had an open-door policy for Upheaval members and served as a safe haven for Rudd’s enduring friendships with Hayes, Harris, and Quinn. LaVelle’s daughter Hedi fondly remembers listening to records and reel-to-reel tapes with Rudd and Hayes (who she affectionately calls “Uncle Joe”). “I knew these guys did some bad things,” she admits, “but they also were guys you could trust your life with; they took care of me.”

IV. The Legacy

The fact that any public knowledge of Upheaval has survived until now is largely due to the only 45 the band committed to vinyl: ‘Paradise Lost’ b/w ‘Now That You’re Gone’ recorded on August 26th, 1974. ‘Paradise Lost’ was Upheaval’s contribution to the discussion of racism, a common thread woven into the shag carpet of the era’s soul music. The song grieves the loss of an unprejudiced society, the recovery of which is yet to materialize.

‘Paradise Lost’ by Upheaval (recorded in 1974, reissued by NowAgain Records in 2021)

It took nearly three decades of circuitous trades before a single copy of ‘Paradise Lost’ fell into the hands of a Las Vegas disc jockey known as DJ John Doe. What DJs and collectors prize above all else are quality and scarcity. ‘Paradise Lost’ satisfies both. Curious about the record’s origin, Doe sent a label scan to Chicago collector Dante Carfagna. Carfagna, in turn, sought the help of Brent Goodsell, a like-minded aficionado of the abstruse. Like a musical private investigator tasked with chasing down a lead, Goodsell tracked Upheaval’s origins by following what limited information there was available: the location of “Custom Records” (Oshkosh, Wisconsin), and the name of one of the credited songwriters (LaVelle Rudd) which was uncommon enough to be traceable.

The search for Rudd was a success, despite the misspelling of his first name on the record (“LaValle”), and he transmitted the oral history of Upheaval to those interested enough to ask just months before he died. For a while, Goodsell had attempted to compile a compendium of Wisconsin soul music, but later dropped the project after a hard drive got lost in a move and he found a general lack of interest from interviewees. Rudd had tapes of Upheaval, many of which had been recorded on cassette live, but decades of circulation among Upheaval band members had left them in poor shape and of insufficient quality to serve as a vehicle for reissue.

Not long after the initial discovery of the first ‘Paradise Lost’ 45, a second copy found its way into the hands of Goodsell’s friend and occasional DJ partner, Andy Noble, a young Milwaukeean collector obsessed with obscure soul and funk. Noble’s foray into record collecting was an act of necessity, rather than choice. As the leader of his high-school band, he felt he needed to absorb as much information as he could about arranging. Coming of age in the early 1990s coincided with the arrival of CDs, which Noble candidly calls “the height of not giving a fuck about records.” CDs being cost-prohibitive for a teenager’s shoestring budget, Noble quickly found that he could stretch his meager allowance by buying records instead, sometimes at four for a quarter. Gradually, collecting became his education, then his passion. Years later, in Milwaukee, when his collection grew to fill his apartment, his landlord suggested that for $250 a month, he would let Noble open a record shop on the first-floor flat of the building. Noble’s parents were art dealers, so he had a hustler’s pedigree, but fortunately, it was a vocation he enjoyed and was good at.

Often, a collector will buy a cache of vinyl from a seller like a prospector staking a claim in which to pan for gold. To know which repositories of records are worth digging through (let alone purchasing) requires an almost encyclopedic knowledge of published music. Dexterous fingers flick through crate after crate of 45s while the mind catalogues expectations from compartmentalized information. An independent film documentary about Andy and his siblings called The Super Noble Brothers demonstrated this skill for the viewer when Noble pulled a record off a shelf at random, noted the artist, album artwork, year it was recorded, and label, and was able to describe in generalities what he expected the record to sound like.

Since soul and funk music’s most prolific years were during the 1960s and ’70s, a lot of records have been sitting in storage or in the possession of hoarders for years, if not decades. Sometimes they tell a story of the owner’s musical taste, or hint at a history of leftover paraphernalia from long-departed lovers. Large collections may reside in Aunt-So-And-So’s damp basement or cobweb-infested storage locker, and only the hardiest of crate diggers remain undeterred. Long before the world became inured to the sight of N95 masks amid the pandemic, seasoned record collectors like Noble regularly donned them like soldiers going into battle. Their adversary: black mold; their objective: to find records of particular value.

Noble found his first copy of ‘Paradise Lost’ (which he retains to this day) while thumbing through a series of worthless Elvis records on a house call. “I lost my absolute shit,” he tells me. Not too long after that, in 2005, he stumbled upon a second copy. After playing it cool and handing the clueless purveyor five dollars in cash, he flipped open his phone and called every collector he knew. Although the copy Noble found was pretty battered, he was able to sell it for $2,000 (and later heard that the same copy eventually sold for over $4,000). Noble’s discovery of two copies of the record caused him to question the apocryphal claim that only 25 copies were ever pressed, given that the plant minimum is typically 500. Goodsell, on the other hand, says he heard the “only 25 copies ever pressed” claim from multiple unrelated sources, and explained that smaller pressings were not uncommon if bands lacked the requisite funds to take advantage of the economies of scale. In any event, Noble estimates that a clean, pristine copy of ‘Paradise Lost,’ should such a thing still exist, would probably fetch over $10,000.

However, Noble’s goals proved to be more ambitious than exclusive proprietorship or to incorporate ‘Paradise Lost’ into his DJ sets (although he did that too, of course). At the time, Noble was the ringleader for the now defunct 10-piece Milwaukee soul outfit Kings Go Forth, a band that in many ways was a byproduct of his record collecting. The first track on the B side of their one and only LP, The Outsiders Are Back, is a cover of ‘Paradise Lost.’ They played it, in part, to pay homage to where they came from—a larger tradition of pride for local soul and funk in which they were active participants, rather than aspiring observers. But they also just loved ‘Paradise Lost.’ “You just really got in the zone when we played it,” he recalls. It had a simple groove song structure, but five guys singing the harmony gave it a solemn power. In October 2010, Kings Go Forth played the track on Austin City Limits, the longest running concert series on television.

‘Come On with the Come On’ by Upheaval (recorded circa. 1974, reissued by Symphonical Records in 2016)

Years after Kings Go Forth played the song for the last time, the legacy of Upheaval continues to repeat itself, falling dormant for years and then finding a resurgence in the soul and funk community. Most recently, Symphonical Records from the UK reissued a 45 of ‘Come On with the Come On’ b/w ‘T.L.C.’ in 2016 and NowAgain Records released a compilation featuring ‘Paradise Lost’ in 2021. Before LaVelle Rudd passed away, he bequeathed his reel to reels and music tapes to his girlfriend. Any Upheaval material still in her possession remains unverified and its whereabouts unknown.

‘TLC’ by Upheaval (recorded circa. 1974, reissued by Symphonical Records in 2016)

At the time of writing, the Waupun Correctional Institution no longer appears to have a music program, nor access to instruments at the prison. As I wind up my interview with Joe Hayes, I ask him what he would want people to know and remember about Upheaval. Almost immediately, I regret asking the question, worried it would dredge up burdensome memories for a man reflecting on some of the most challenging years of his life. He gazes away, and an involuntary wince deepens the crow’s feet at the corners of his eyes. The impression he gives is one of profound friendship and reliance upon one another: “We had to leave the outside, outside.”

Put another way, surviving prison required an ability to navigate the day-to-day reality of incarceration. The collective struggle that Upheaval experienced allowed them to lean on each other, and this solidarity shines through in their music. Hayes’s words echo those written by his friend and fellow band member Eddie Quinn because Upheaval’s story ultimately parallels that of soul music itself. They made the most of a difficult situation, and captured its tribulation and redemption—it was a genuine expression of who they were. The denouement of Quinn’s 50 year-old musings on soul music ends bluntly: “If you aren’t a bit human, then you were lost from the beginning.”

Members and associates of Upheaval (likely incomplete): Blaine Atkinson, Curtis Bowers, Bruce Brandl, Jesse Edwards, William Gray, James Harris, Joseph Hayes, George Heflin, Everett Helm, Larry Holley, James Lampkins, Charles May, James Preston, Eddie Quinn, LaVelle Rudd, Melvin Torrence, James Turner, Ernie Warren, Ardell Williams, Ronnie Wirth.