Modern politics has always been replete with issues about which people feel passionate, sometimes aggressively so. But the culture wars currently raging in the US, Canada, and across much of the industrialized West seem to be particularly fraught. In my 50-plus years, I have never seen so much anger and hostility among citizens of otherwise stable countries. Some of these people will participate in protests or engage in civil disobedience, but many more will employ the political meme to express their discontent. Given how widespread the phenomenon has become, it’s worth asking whether political memes actually advance advocacy goals and our knowledge of important issues, or if they simply feed an unconstructive cycle of anger, misinformation, and polarization.

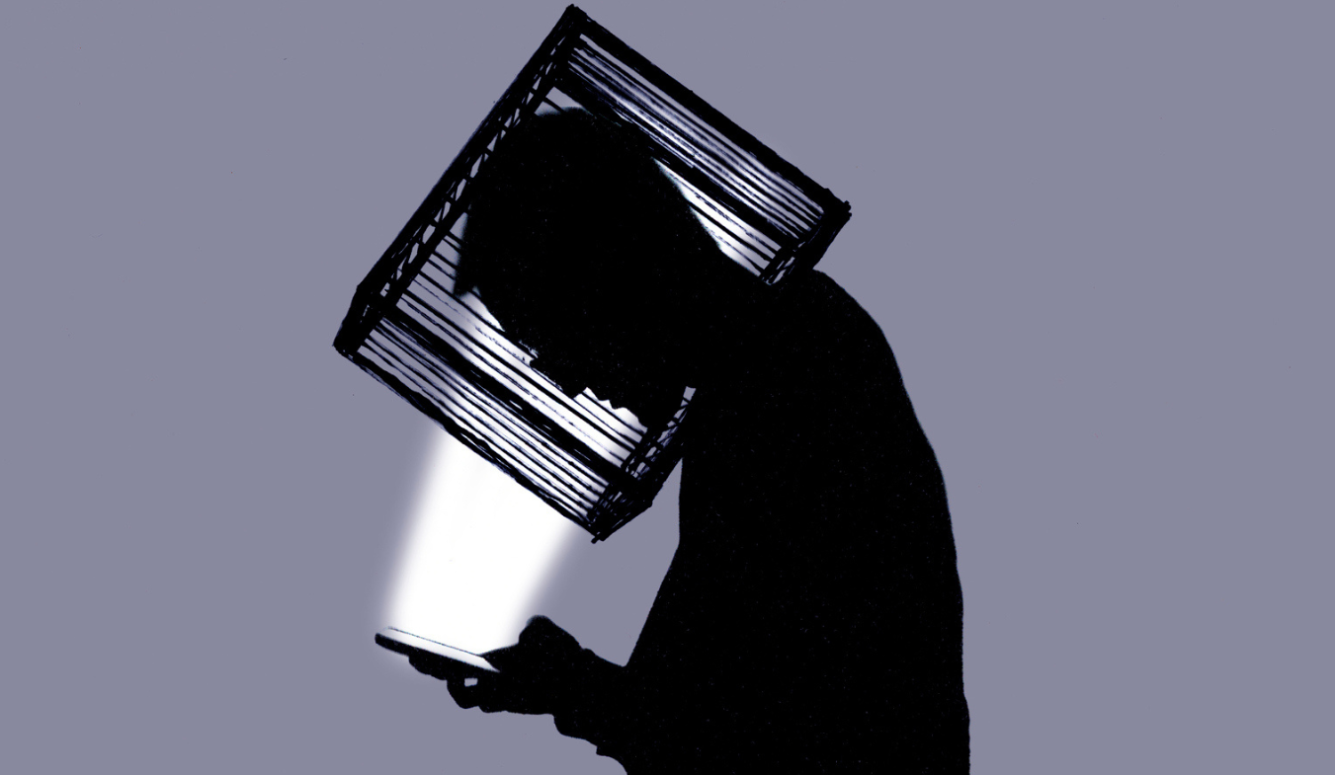

The term “meme” was coined by Richard Dawkins, who used it to describe units of culture, socially transmitted and imitated across generations in ways synonymous with genes—adaptive ideas survive, while maladaptive ideas perish. But in the social media age, the word usually refers to “an image, video, piece of text, etc., that is copied and spread rapidly by Internet users often with slight variations.” The subset of memes that focus on politics are generally designed to boil complex issues down to a digestible combination of emotive image and sloganeering text that flatters those who agree with its message and provokes those who do not.

Most academics who study memes agree that they are poisonous to healthy public discourse (“toxic” is a word that crops up a lot, even in the scholarly literature). One scholar bluntly called them “one of the main vehicles for misinformation,” and they tend to distort reality in several ways. By their very nature, they leave no room for nuance or complexity, and so they are frequently misleading; they tend to lean heavily on scornful condescension and moral sanctimony (usually, the intended takeaway is that anyone who agrees with the point of view being—inaccurately—mocked is an imbecile); they make copious use of ad hominem attacks, straw man fallacies, and motte-and-bailey arguments; they intentionally catastrophize, generalize, personalize, and encourage dichotomous thinking; and they are aggressive and sometimes dehumanizing. They are, in other words, methods of Internet communication that display all the symptoms of a borderline personality type of mental disorder. Of course, it’s possible to construct a meme that is short yet still thoughtful and sophisticated, but these are few and far between.

The best evidence we have today is incomplete and limited, but it suggests that political memes have a net negative effect on society. If the idea is to persuade or advance practical advocacy goals, then there is little evidence that they work. To the contrary, they may be counterproductive—the evidence we do have suggests that they contribute to political polarization, distort issues in the name of political expediency, and provoke indignation, hatred, and intolerance (on both sides of the political spectrum). Yes, the available evidence is fragmentary and would certainly benefit from better and more open science designs. However, it accords with larger observations about social media and political polarization. Perhaps new and better research will reveal that alarm about the negative effects of memes is simply another moral panic comparable to those that arose around video games or smoking in movies. But since memes add almost nothing to public discourse that would offset the risks, it’s probably worth hesitating before sharing them.

During my time on social media, I’ve noticed that many of the people who complain about our political and cultural polarization—and social media’s role in it, specifically—nonetheless gleefully participate in one of the more evident examples of its toxicity. These aren’t random anons on the Internet, but mainly Facebook friends I’ve known and liked for years. Until perhaps five years ago, they seemed like intelligent and rational individuals without melted brains. I’ve sometimes engaged with meme sharers in an attempt to glean a sense of their motivation, but these exchanges are seldom productive. People get strangely protective of memes, and become much more defensive when challenged than if an op-ed they’ve shared is disputed. Longer form communications seem to be open to rigorous but respectful debate in ways that memes are not. It doesn’t appear to matter whether one attempts to debate the content of the meme itself, or the practice of sharing memes—criticizing a meme can feel tantamount to insulting someone’s child.

This may be partly because political memes invariably flatten political and ethical complexity into binary narratives of good and evil. They are cast as profound moral statements signaling allegiance to the in-group, and so they are meant to attract approval (likes, reshares, and praise) not discussion or objections. Certainly, many op-eds are partisan garbage, but political memes are a compact version of all that is wrong with modern discourse. To suggest that someone’s virtuous declaration is actually just the kind of spiteful dishonesty they say they deplore in opponents is likely to produce significant cognitive dissonance. The most common retort—that it’s “just a joke”—is unsatisfactory. Bipartisan memes can also be funny, but the whole point of the political meme is to deride and humiliate. They are bullying dressed as humor.

Another common response is “They did it first” or “They deserve it,” the kind of argument we are taught is irrelevant in kindergarten. If the other side has misbehaved, how does it help to respond with the same kind of misbehavior? “I am playing them at their own game” and “holding them to their own standards” is a poor and self-serving move—once you participate in the game according to those standards, they become your standards too. The upshot is a downward spiral of mutually destructive conduct in which the only motivation is to outdo an opponent. In psychology, blindness to one’s own faults and hypersensitivity to an opponent’s (even when they are identical) is called myside bias. And this is particularly prevalent in the tribal warfare waged on social media.

Political memes are calls-to-action, and they offer a cost-free means of engaging in advocacy that requires very little of the individual in terms of time or resources. But in that sense, they represent a kind of faux-advocacy because there’s little evidence that they do much to effect real-world policy change. If anything, the derision and complacency in which they trade almost certainly turns potential allies off. That just leaves the true believers to like and recirculate such content within an increasingly conformist echo chamber. The incentives are perverse.

Political memes are most likely ignored by most of the populace, or at least those who are not perpetually online. But they serve as a cheap kind of holy writ for the obedient foot-soldier on the Right or the Left, further circumscribing their ability to think critically or acknowledge the possibility of error. You can’t be a good Republican unless you believe Democrats want to steal every election. You can’t be a good Democrat unless you believe Republicans want to create a fascist state modeled on The Handmaid’s Tale (and yes, I know some people reading this are crying “But they do!”).

Political memes are basically a doorway into stupidity and misery. Seeing a fair number of people I know and respect walk through that door has been a depressing but eye-opening experience. But these poor unfortunates are rubes: victims of a business model centered on stoking outrage and conflict. We need to find ways to understand our opponents better. They are, after all, our fellow citizens. We could start by taking a straightforward step in the right direction: Stop sharing political memes.