Science

Science and Civil Liberties: The Lost ACLU Lecture of Carl Sagan

Around 1987, Sagan gave an uncannily prescient lecture to the Illinois state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

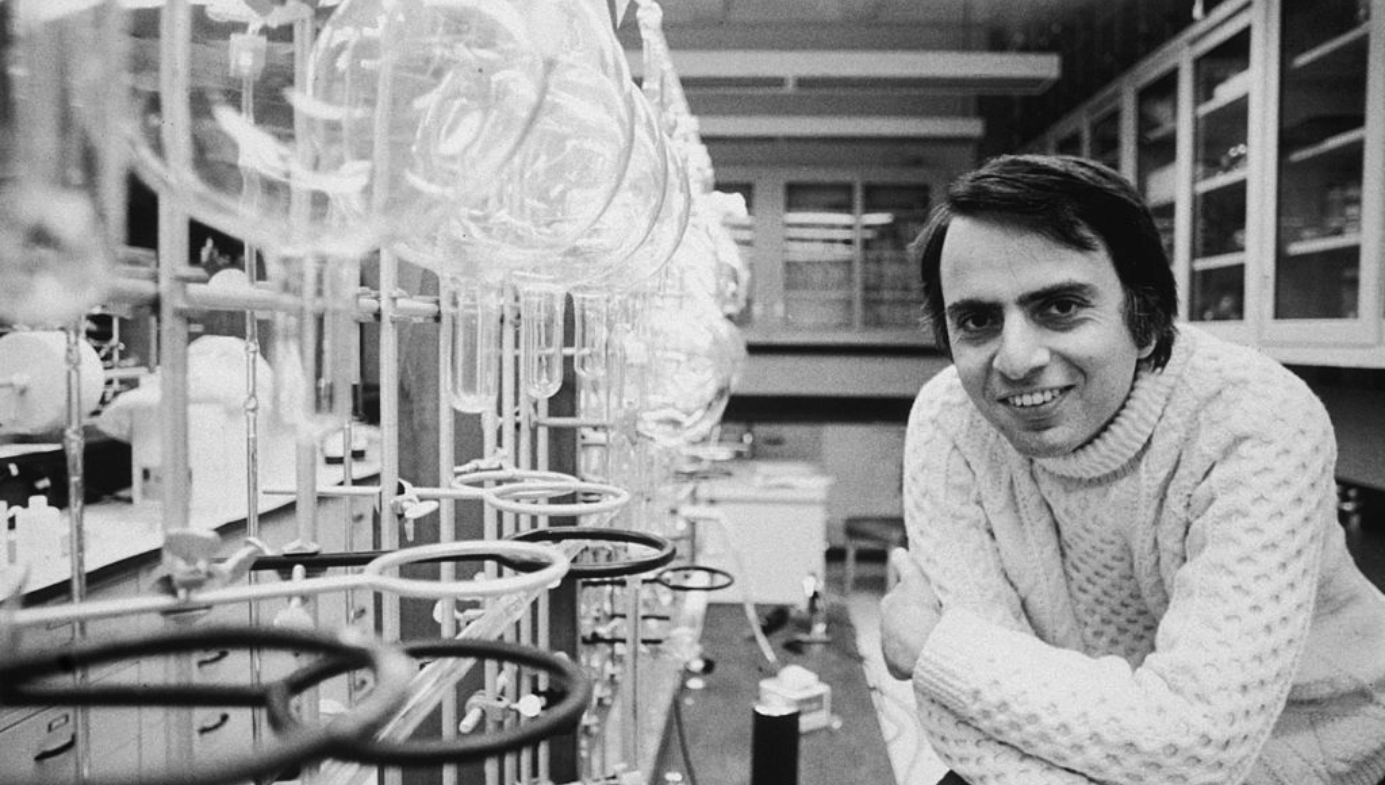

The astronomer, science communicator, thinker, writer, and teacher Carl Sagan (1934–1996) had an influence as a scientist that is almost unimaginable today. Together with his many scientific contributions (including his analyses of the origins of life, his discovery of the temperature of Venus and its connection to the greenhouse effect, and his work on nuclear winter), Sagan played a leading role in every NASA spacecraft mission of exploration until his death, designed the first physical messages sent into space, co-wrote with Ann Druyan and starred in Cosmos, a television documentary series watched by half a billion people worldwide, wrote the sci-fi novel Contact, which became a major film, and made frequent appearances on The Tonight Show and in essays for Parade magazine, the weekend supplement to hundreds of American newspapers.

Around 1987, Sagan gave an uncannily prescient lecture to the Illinois state chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union on the intersection between his area of expertise and theirs. We were fortunate to obtain a recording of that lecture, which we have transcribed, lightly edited, and annotated to update its historical allusions and contemporary relevance. Sagan spoke prophetically of the irrationality that plagued public discourse, the imperative of international cooperation, the dangers posed by advances in technology, and the threats to free speech and democracy in the United States. A 35-year retrospective

reveals both increments of progress (some owing to Sagan’s own efforts) and

continuing menaces.

Most importantly, he highlighted the virtues common to science and civil liberties that are needed to deal with these challenges: freedom of speech, skepticism, constraints on authority, openness to opposing arguments, and an acknowledgment of one’s own fallibility.

The two of us, a cognitive scientist and a civil liberties lawyer, are presenting this lecture to the public at a time when Sagan’s insights are needed even more urgently than they were when originally expressed. We do so with the kind permission of Ann Druyan, Sagan’s widow and longtime collaborator.

Steven Pinker, Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology, Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts

Harvey Silverglate, Criminal Defense and Civil Liberties Lawyer and Writer Cambridge, Massachusetts

Earlier this month I was in Moscow, and in a lovely long dinner, a prominent Soviet intellectual gave a toast. It went something like this. “To the Americans,” he said. “They have some freedoms.” He paused and then said, “And they know how to keep them.”

Is this true? Technology is rushing on apace, and there are propagating consequences of new technologies which put us in directions that are sometimes wholly unexpected.

The first consequence of this is that we must have a broadly diffused understanding of science and technology—otherwise, how will we possibly reach rational adjustments and accommodations to these new technologies? For example, there is a category of technological developments which are already knocking on the door which have serious negative consequences, and which have solutions that can only be transnational. They therefore have implications about national sovereignty and the ways that nations interact among themselves that are in many respects new.

For example, the chlorofluorocarbons, which threaten the protective ozone layer, are wholly ignorant of national boundaries. They have no idea what supreme national interest means. Chlorofluorocarbon that is generated in the Soviet Union destroys ozone in the United States and vice versa.[1]

The same is true for carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases produced by the burning of fossil fuels. Those gases are distributed worldwide. It is no good for just a few nations to decide not to burn fossil fuels because of concern about the Earth’s climate. The entire fossil fuel–burning community of nations must do so for it to be effective.[2]

A leak in a Soviet nuclear reactor threatens the economy and well-being in Lapland—dozens of nations are affected.[3] The same thing is true for many other inadvertent consequences of modern technology, acid rain for example.[4] It’s true also for AIDS because of the fact that the planet is a sexually inter-communicating whole.[5] The only solutions to these sorts of problems are on a global scale.

There are certainly many other obvious civil liberties–technology interactions, ranging from mercury in the drinking water,[6] to how do we guarantee a diversity of views expressed in media which are owned by the very wealthy,[7] to issues of population and birth control,[8] genetic engineering, biotechnology,[9] and so on.

The area which is perhaps most interesting, most perilous, and most significant in this respect is the issue of the global nuclear arms race—the United States and the Soviet Union having rigged the planet with 60,000 nuclear weapons—and tremulously we are exploring a new kind of regime of massive bilateral and intrusively verified arms reduction. That intrusive verification—that onsite inspection—has a very large number of civil liberties questions attached to it, which I believe we will have to deal with if the trend continues, as I hope it will.[10]

Another aspect of this is the clear fact that while the Constitution specifies that only Congress can declare a war. The technology of nuclear weapon delivery systems is such that nuclear weapons can be delivered halfway across the planet in 20 minutes or less, and, therefore, Congress cannot even be convened, much less consulted, on urgent issues connected with nuclear war. And this demonstrates—and there are other kinds of demonstrations—that you can design a technology that subverts the Constitution.

And I believe that we will see many other such places where technologies that were wholly unimagined by the founding fathers make serious problems for the Constitution. On the issue of technology, I just want to continue for a moment. The incidents at Chernobyl [April 1986] and the catastrophic failure of the space shuttle Challenger [January 1986] are reminders that high technology in which enormous amounts of national prestige have been invested can, nevertheless, fail spectacularly. They are, in turn, reminders that pervasive human and machine errors exist—that there is an institutional fallibility even where you would think the best effort had been made to avoid such failures, in areas in which the stakes are extremely high.

The conclusion is that we desperately need error-correcting mechanisms. We are fallible. We’re only human. We make mistakes. We have a set of new technologies that, in many cases, we barely know how to control. Those in charge pretend otherwise. The question is how do we make sure that the most serious sorts of errors do not occur?[11]

Now there is another area of human activity that has to face the same issues, and that’s the area called science. Science has devised a set of rules of thinking, of analysis, which, although there are exceptions in individual cases (scientists being humans just like everybody else), nevertheless, on average, are responsible for the remarkable progress of science.

And you all know, certainly, what these rules are. Things like arguments from authority have little weight. Like contentions have to be demonstrable. Like experiments must be repeatable.[12] Like vigorous substantive debate is encouraged and is considered the lifeblood of science. Like serious critical thinking and skepticism addressed to new and even old claims is not just permissible, but is encouraged, is desirable, is the lifeblood of science.[13] There is a creative tension between openness to new ideas and rigorous skeptical scrutiny.

This set of habits of thought could also, in principle, contribute to the kind of error-correction mechanism that is desperately needed in the society that we are generating. In public affairs, this sort of error-correction machinery in our society is institutionalized in the Constitution. It’s institutionalized, first of all, in the separation of powers, and secondly, in the civil liberties, especially in the first 10 amendments to the Constitution: the Bill of Rights.

The founding fathers mistrusted government power, and they had very good reason to, as do we. This is why they tried to institutionalize the separation of powers, the right to think, the right to speak, to be heard, to assemble, to complain to the government about its abuses, to be able to vote or impeach malefactors out of office.

John Stuart Mill talked eloquently in his essay On Liberty—which, by the way, is an underground bestseller in the Soviet Union these days, which is another good sign coming out of there [14]—on the importance of free speech, of vigorous interaction. Let me just make one quote here from On Liberty:

The peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is that it is robbing the human race; posterity as well as the existing generations, those who dissent from the opinion still more than those who hold it. If the opinion is right, they are deprived of the opportunity of exchanging error for truth. If wrong, they lose what is almost as great a benefit: the clearer perception and livelier impression of truth produced by its collision with error.

Despite our best efforts, some things we believe are probably wrong. We certainly are very keen on recognizing the errors of past times and other nations. Why should our nation, why should our time, be different? If there are things that we believe, if there are institutions in our society that are in error, imperfectly conceived or executed, these are potential impediments to our survival. How do we find the errors? How do we correct them?

I maintain: with courage, the scientific method, and the Constitution. Sooner or later, every abuse of power must confront the Constitution. The only question is how much damage has been done in the interim.

Now, it’s no good to have such rights if they’re not used: a right of free speech when no one challenges the government; a right of assembly when there are no protests; universal suffrage when much less than half the eligible electorate votes, and so on. It is not enough merely to have these rights in principle; we must exercise them in practice. And the Constitution itself is not only a body of knowledge fundamentally about human behavior, but also a continuing and adaptive process. In some sense, the Supreme Court, when it sits, is a continuing Constitutional convention.

Mill said, “If society lets any considerable number of its members grow up as mere children, incapable of being acted on by rational consideration of distant motives, society has itself to blame.” And Thomas Jefferson said the same thing, in somewhat stronger words. He said, “If a nation expects to be ignorant and free in a state of civilization, it expects what never was and never will be.”

Education on the nature of civil liberties, on the need for them, on how to exercise them, is an essential part of the democratic process, and it seems to me almost pointless to have these rights without their exercise. Now, in every nation—certainly in ours; certainly in the Soviet Union—there are a set of forbidden thoughts, which its citizenry and adherents are, at any cost, not to be permitted to think seriously about. (By the way, Mill’s book On Liberty itself was in that category in many places in many times and was denounced and banned as “dangerous thoughts” by, of all people, the Emperor Hirohito on the eve of the Second World War—one of many indications that it’s a good book to read.)

These forbidden thoughts in the Soviet Union—at least until recently—include capitalism, God, and also the surrender of national sovereignty. In the United States, among the forbidden thoughts are socialism, atheism,[15] and also the surrender of national sovereignty—one point of agreement at least.[16]

If we are agreed that there is nothing we can be absolutely sure about, that we have no monopoly on the truth, that there is something to be learned, why is each side so frightened about having the principles of the other expounded? Why, on Soviet television, is there no serious and systematic exposition of the presumptive virtues of free enterprise by someone who holds those views? Why, on American television, is there no consistent exposition of socialism and its purported virtues by people who hold those points of view? What is each side afraid of? What’s wrong with a little understanding of what the other side believes? Maybe there is something that can be understood. Maybe there is something that can be used. The fact that both sides are so reluctant to have the philosophy and theology of the other expounded to its people suggests that neither side is fully confident that it has convinced its own people of the truth of its doctrine. And that, of course, is a dangerous circumstance.

Mill argues in such a case that alternative opinions must be heard from persons who actually believe them, who defend them in earnest, who do their very utmost for them. We must know them in their most plausible and persuasive form, and not by the propagandists for each side talking to its own citizenry. One goal, it seems to me, of each side ought to be, at the very least, to be able to present the point of view of the other side in a form sufficiently coherent for the other side to say “Yes indeed, that is my position.”[17] It seems to me at any summit, the president of the United States ought to be able to make a coherent exposition of what the Soviet point of view is—he doesn’t have to agree with it—and the Soviet general secretary should be able to make a coherent exposition of what the American point of view is. How can they negotiate if they don’t understand each other’s position well enough to state it?

One of the dangers when a democracy is in confrontation with a totalitarian adversary is that the democracy slowly, perhaps unwittingly, becomes more and more like the adversary. Democracies are in danger of losing the very thing that they are ostensibly fighting for—and this is one of many reasons it seems to me why Americans should welcome and support the Gorbachev revolution that is going on—for how long we do not know—in the Soviet Union. If there is any place in the world where an extremely steep gradient, a steep rate of change in the views on the virtues of civil liberties is happening, it’s, astonishingly, in the Soviet Union today.[18]

Well, to conclude about this country: during the last decade, it seems to me there has been a terrible backsliding on Constitutional and democratic issues in this country. I don’t just mean that the regulatory agencies are, by and large, in the hands of those being regulated. I don’t just mean that arms control is in the hands of those who are in favor of the arms race. I don’t just mean that social justice is being administered by the ideologues of privilege. I don’t just mean that government agencies designed to protect people’s rights are in the hands of those who would abolish those agencies. And I don’t even just mean that there is what seems to be a conspiracy of high government officials to subvert the Constitution (I’m referring to Irangate.[19]) It’s not just that.

It’s also that there has been a serious erosion of the tradition of skeptical inquiry, of vigorous challenging of government leaders, of public exposure of what the government is actually doing, rather than mere pomp and rhetoric. And it is in this area—skeptical scrutiny, public exposure—where the largest strides, in my opinion, are needed.

Civil libertarians must do more to explain exactly why civil liberties and their vigorous exercise are essential—essential not just to retain what freedoms we have that are, astonishingly, toasted by leading figures in countries we have been taught to think of as our adversaries, but also an exercise in the application of civil liberties that are necessary for our very survival.

Copyright notice: Druyan-Sagan Associates 2022 All rights reserved

In September 1987, the Montreal Protocol, designed to protect the ozone layer by phasing out chlorofluorocarbons and related hydrocarbons, was signed by several dozen nations, and then ratified by every member of the UN, together with the EU and the Holy See. It has been credited with reversing the process of ozone layer depletion. ↩︎

In 2015, the Paris Agreement, designed to limit global warming to below two degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, was signed, and has been ratified by 192 states and the EU. The United States withdrew from the agreement in November 2020 but rejoined it in February 2021. ↩︎

In the wake of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant accident in 1986, The Convention on Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident was adopted. It “established a notification system for nuclear accidents from which a release of radioactive material occurs or is likely to occur and which has resulted or may result in an international transboundary release that could be of radiological safety significance for another State.” ↩︎

Many domestic regulations and international treaties aimed to reduce acid rain have been implemented, including the Helsinki Protocol in 1985, the Air Quality Agreement of 1991, and agreements among ten Asian countries beginning in 2000. According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, the American Acid Rain Program “has delivered significant reductions of sulfur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOX) emissions from fossil fuel–fired power plants, extensive environmental and human health benefits, and far-lower-than-expected costs.” ↩︎

Thanks to the development of antiretroviral drug therapies and programs to promote treatment and prevention globally, including the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, the global number of deaths from HIV/AIDs fell by half in the second decade of the 21st century, though the disease still kills a million people a year. ↩︎

In 1991, the EPA implemented the Safe Drinking Water Act, setting an enforceable regulation for inorganic mercury in public water systems. ↩︎

In a development Sagan could not have foreseen, concerns in the 1980s about wealthy media companies allowing only a narrow range of opinions to be expressed have been supplemented by concerns over wealthy media companies (particularly cable news networks and social media platforms) fostering political polarization, “filter bubbles,” and extremist rabbit holes. ↩︎

Though a runaway population explosion was a major concern of the 20th century, when the world’s population quadrupled, it has recently become apparent that rapid population growth has ended in developed countries, whose populations are set to shrink, and that the population of the world, as a whole, will stabilize by the century’s end. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, in the US, birth rates in 2020 dropped by four percent from 2019 and have been in decline since 2014. In fact, 2020 has had the lowest number of births since 1979. ↩︎

Sagan wrote this well before the announcement of the cloning of Dolly the sheep (1997), the completion of the first draft of the human genome (2000), the widespread use of preimplantation genetic diagnosis (1990s) and invention of the gene-editing technique CRISPR-Cas9 (2012). Concerns about the risks and promises of biotechnology have, accordingly, intensified. ↩︎

It has, at least for now. The estimated number of warheads in the world’s nuclear stockpiles has declined from more than 64,000 in 1986 to 9,400 in 2022. Part of the credit goes to Sagan, whose warnings of nuclear winter were cited by Gorbachev in his discussions with the US on the need for limiting nuclear weapons. The US and USSR/Russa signed several treaties limiting nuclear arms, but only one, New START, remains in force, and it is set to expire in 2026, leading to concerns about a new nuclear arms race. ↩︎

In this passage, Sagan anticipated by three decades the study of “existential risk,” now the focus of several books (such as Toby Ord’s 2020 The Precipice) and research centers (such as the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, the Future of Life Institute, and the Global Catastrophic Risk Institute). Though Sagan does not mention it here, his warning about nuclear winter in 1983 was the first systematic and widely publicized analysis of a manmade human extinction event. ↩︎

The replicability of scientific findings emerged as a major issue in the 21st century; see Stuart Ritchie’s Science Fictions (2021). ↩︎

Arguments from authority and the repression of substantive debate and skepticism have become increasingly serious threats to science. See, for example, Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff’s The Coddling of the American Mind (2018) and the many assaults on debate in science reported on the website of the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (www.thefire.org). ↩︎

Following a period of “glasnost” (openness) and “perestroika” (reorganization) beginning in 1985, when Mikhail Gorbachev came to power, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics collapsed in December 1991, ushering in a period of limited democracy. It was gradually superseded by the electoral autocracy of Vladimir Putin, particularly at the end of Putin’s first term as president in 2008. ↩︎

Since Sagan’s time the taboo against socialism in American politics has been shattered by popular (albeit controversial) politicians who have embraced the once-forbidden label, including Senator (and candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination) Bernie Sanders and Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. ↩︎

Though Putin’s Russian nationalism, culminating in his 2022 invasion of Ukraine, are particularly egregious assertions of national sovereignty in defiance of international law, the United States also has a history of refusing to sign or ratify international treaties, including those establishing the Law of the Sea and the International Criminal Court, and those banning torture, land mines, and cluster munitions. This rejection of international cooperation came to the fore with the rise of Donald Trump’s populist nationalism in 2016, which justified his withdrawing the US from the Paris Climate Agreement. Sagan’s observation that “the surrender of national sovereignty” is a “forbidden thought” in both countries remains relevant. ↩︎

The ability to state opponents’ positions accurately has recently been highlighted as a cardinal virtue of critical thinking and the new “rationality” movement; see, for example, Julia Galef’s 2021 The Scout Mindset. ↩︎

See note 15. ↩︎

Also known as Iran-Contra, the secret program that began in 1981 and was exposed in 1986, in which Reagan administration officials facilitated the sale of weapons to Iran, then the target of an arms embargo, with the proceeds directed to aid the anti-communist Contra insurgents in Nicaragua, also illegal at the time. ↩︎