Politics

Privilege-Checking in a World on Fire

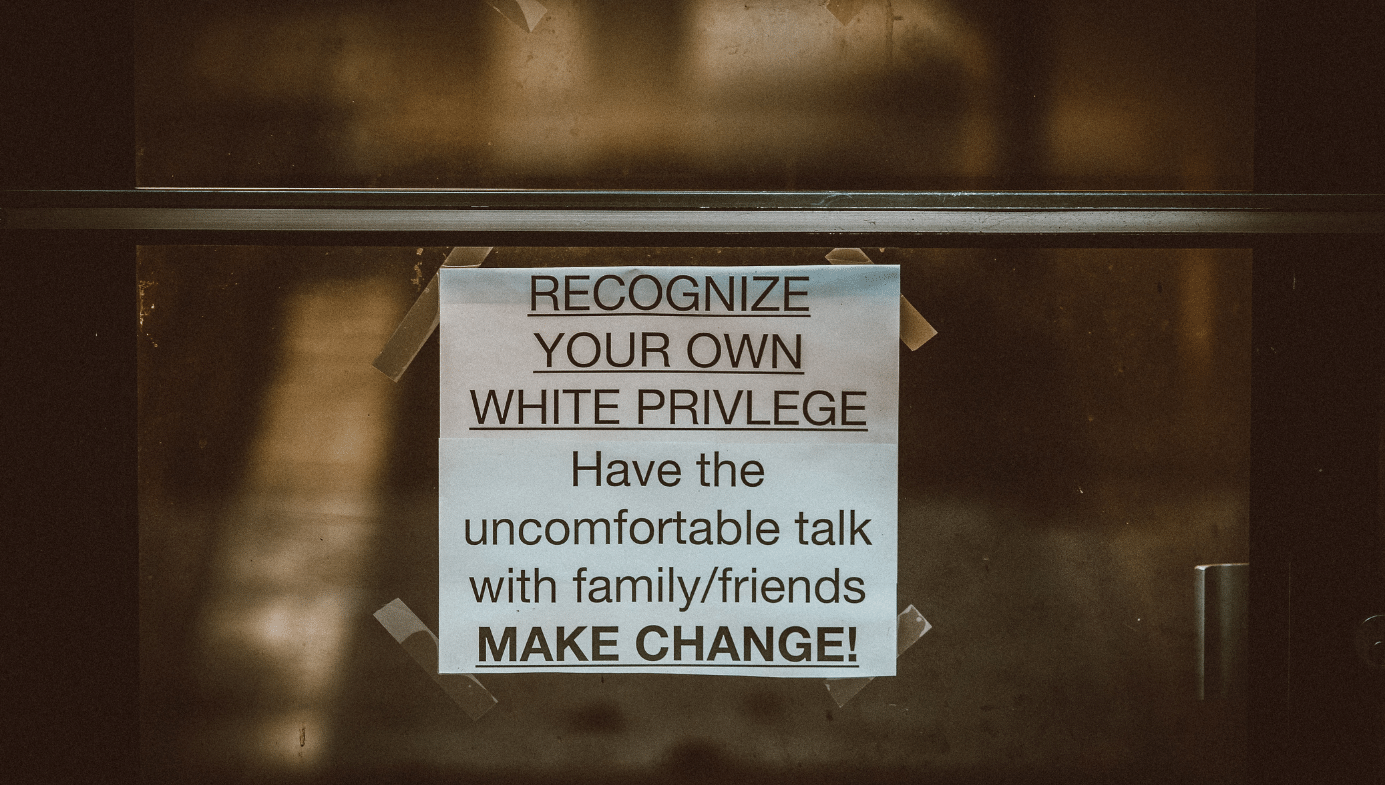

Privilege is a sham mark of opprobrium—those who decry the privilege of others tend to want more of it for themselves. The dissemblance is all the more distasteful given that the detractors of privilege typically possess, comparatively speaking, an abundance of it. One need not be conversant in history to realize as much. It is enough to simply survey the present. To deplore the unearned structural advantages maintained by white males at a time when Ukrainian cities fall and casualties rise reflects not only poor taste, but poor judgement. It bespeaks an insensitivity or obtuseness that today’s self-designated and self-righteous victims routinely ascribe to those the system is reputed to benefit.

No doubt there are beneficiaries. All societies are comprised of those who are advantaged and those who are not—an enduring reality of human existence, as the egregious inequalities that persisted in every society devoted to stamping them out attest. But to suggest that in America, privilege is parceled out neatly on the basis of skin color and chromosomal composition is ill-considered at best. It ought to suffice to allude to Appalachian whites, Indian Americans, and a growing gender gap favoring women in higher education to give the lie to the duplicitous platitudes that masquerade as incontrovertible truths in the present day.

But it is when one turns one’s gaze from America to the so-called global community that the narrow-mindedness of those who obsess about privilege becomes most glaring. Anyone with the luxury to fret about microaggressions in a world riven by macroaggressions is privileged. Anyone with the liberty to assign himself idiosyncratic pronouns, oblige others to adopt them, and punish those who do not comply knows a good deal of privilege. Everyone who has never had his city shelled; never been forcibly displaced from his home; never had to take up arms to defend his life against an invading army is, as current events make plain, tremendously privileged.

It is an especially blinkered and self-absorbed individual who fails to appreciate as much; the sort of person who petulantly demands that his views not only be heard but validated. (Another privilege retained by those who stridently lament their lack of it: the license to expunge from history those deemed to be on the wrong side of it. The power to rewrite the past and the rules of grammar with it! Have underprivileged people with so much privilege ever before roamed the earth?) That education in America is bent on breeding such minds—minds ill-equipped to contemplate the human condition and comprehend the complexities (moral, political, material, etc.) that attend life in every era—must be ranked one of its greatest failings. If only minds so ill-prepared to judge were not so quick to do so. Alas…

To be fair, the widespread myopia that afflicts so many today appears to be congenital and what is worse, degenerative—a condition endemic to an age of universal haste and distraction. The declining attention span of the digital denizen ought to dispel the conceit that human sapience accrues generationally. To make matters worse, it is not just that attention spans are in decline, but that what people devote their limited attention to is subject to shameless manipulation. At a time when individuals—the ostensibly underprivileged not least among them—incessantly boast about their agency and autonomy and intentionality, it is painfully obvious that what preoccupies them is not self-determined.

Following two years of around-the-clock coverage of COVID, during which time people were impelled to agonize about the virus, the news suddenly stopped. Or rather, it shifted focus. And in lockstep, the American people shifted theirs too. Obsession with COVID has given way to obsession with Ukraine. The transition was made so seamlessly and with such celerity that one wonders what the talking heads would be droning on about had Putin decided not to launch an invasion. Whatever might have been pronounced newsworthy, there can be no doubt that the ongoing hostilities and resulting humanitarian crises in Myanmar, Yemen, Syria, Sudan, Ethiopia, Mali, the Central African Republic, Burkina Faso (where?), or any of the scores of other war-torn and neglected corners of the globe would remain news-unworthy.

Of course, the geopolitical consequences of the conflict in Ukraine are disproportionately portentous, but the fact remains that before a laser pointer was shone on Ukraine, most Americans would have been hard-pressed to locate it on a map. This is not to suggest that one should be unmoved by the plight of the Ukrainian people; only that from a humanitarian perspective, one should be no less concerned about the plight of Myanmarese, Yemeni, Syrian, and Central African people. (Indeed, given the preponderately pale complexions of the Ukrainian people, they—per the scales of social justice—deserve less consideration and compassion. Unlike Lady Justice, social justice is not blind, and emphatically not colorblind.) Furthermore, their plights should highlight the privilege of those who do not share them. If you find yourself safely removed from a conflict zone, so safely that there is no credible prospect of suddenly finding yourself in one, you’ve got privilege and you might want to check yours (whatever that means) before you castigate others for theirs.

Of course, to (re)draw attention to the vacuity of contemporary privilege-talk, the unearned privilege that comes with being born in America amounts to much more than finding yourself far and safely removed from the many theaters of war that riddle the world at every moment. In terms of wealth, comfort, and freedom, Americans enjoy privileges the vast majority of people the world over will never know. Whatever their gender or race may be, Americans are, in an impolitic manner of speaking, the white males of the global village.

Such gross generalizations are intended less to offend than to encourage those who make commensurately gross generalizations (about whites in America, for instance) to reexamine their rhetoric. It is not just that this contemporary fixation with privilege is hollow; it is pernicious. Privilege, however one wishes to characterize it, does not immunize those who possess it from misfortune. When pricked, they too bleed. The regressive tendency to categorize people on the basis of their skin color, class, gender, sexual orientation, and so forth, and then to intersectionally assess their merit, is dehumanizing. It forestalls sympathy, fosters resentment, and promotes an endless cycle of recrimination that precludes reconciliation and incites people to tear one another apart.

For much of history, the ability to see the humanity of others—of those removed from and foreign to oneself—was uncommon; a capacity reserved for elevated and enlightened souls sparsely dispersed across the ages. As the distance between man and man has diminished over time, that capacity has become more and more accessible; a virtue no longer reserved for saints and sages, but within the reach of everyone. It is a precious gift—a privilege, one dare say—one that ironically is in jeopardy of being squandered by those who prattle unceasingly about privilege and in so doing, cannot see past the privileges of others nor apprehend their own.