Politics

PJ O’Rourke—A Tribute

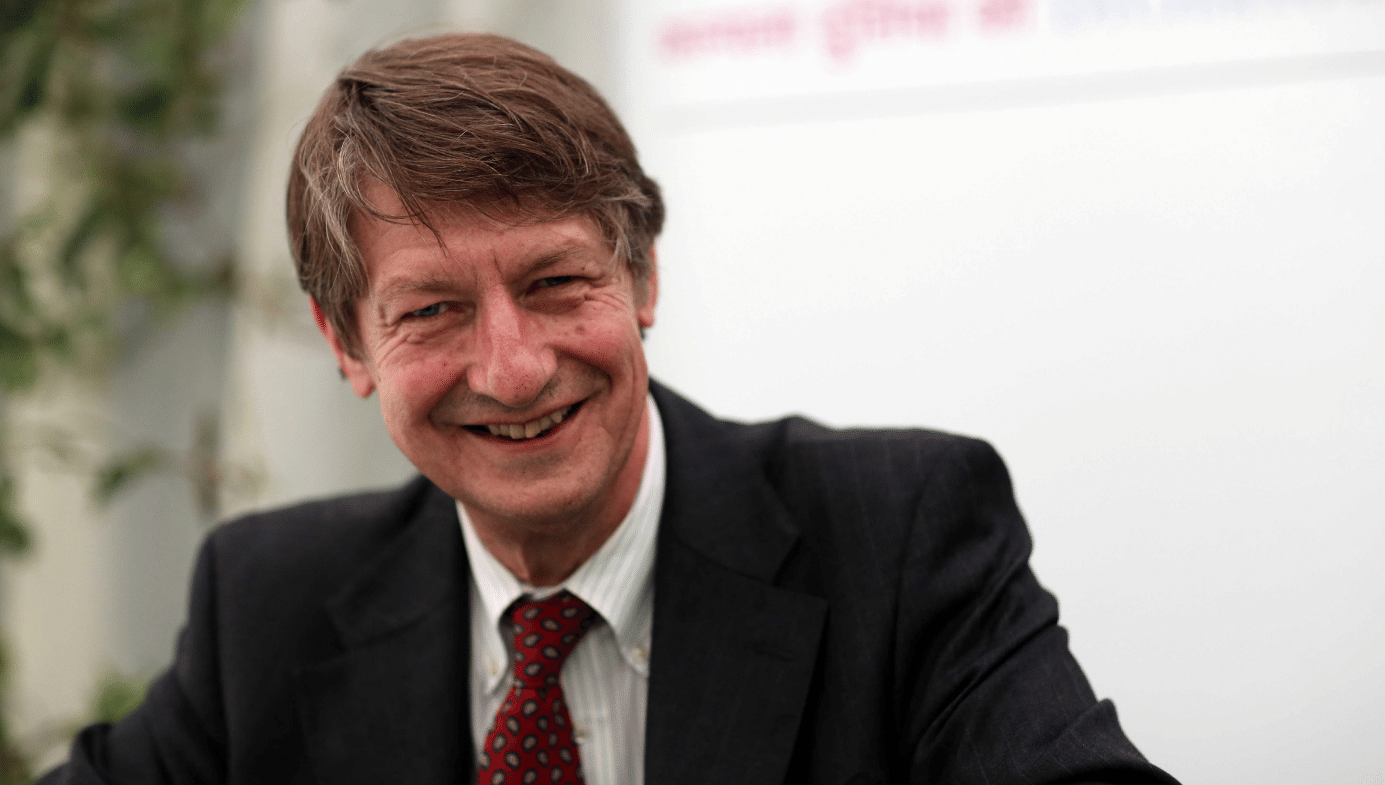

The thing about PJ O’Rourke, who passed away on Tuesday at the age of 74, was that everyone wanted to be around him. By “everyone,” I don’t just mean the right-wingers I hang out with, most of whom share PJ’s classical-liberal politics, but also neoconservatives like Bill Kristol and John Podhoretz, who also loved him, and a number of leftists. PJ wrote much of his best stuff for Jann Wenner at Rolling Stone.

The attraction that PJ had for these disparate people was simple. PJ O’Rourke was an incomparable companion. I looked forward to a dinner with PJ (i.e., an evening of drinking with PJ) with the same anticipation that I long ago looked forward to first dates. I was sad when PJ relocated from Washington to New Hampshire, even though I could still read his writing, because I knew how much I would miss the pleasure of his presence. He could be puckish. He could be delightfully self-deprecatory. His wit could be demurely wicked—comparing Clinton to Trump, PJ observed that while Hillary was wrong about absolutely everything, “she is wrong within normal parameters.” And yet I cannot recall a single instance, no matter how many times the bottle had gone round, when PJ was malicious. The PJ I knew was gentlemanly. It was as much a part of his persona as the humor.

PJ’s wonderful presence obscures how serious and smart his best work was. I’m sure others have their own favorites, but in my opinion Parliament of Whores (1991) is one of the most insightful accounts of America’s dysfunctional federal government, and All the Trouble in the World (1994) is one of the most insightful accounts of the West’s dysfunctional international development policies. Both books are hilarious, but the humor belies the sophistication of his analysis, underwritten by PJ’s mastery of the relevant literature and dogged journalistic reporting.

PJ did not pontificate about world famine from his fashionable Washington apartment or, later, from his home in small-town New Hampshire. He actually went to places like Bangladesh or, even more daringly, to Washington’s regulatory agencies. He actually talked to the people who implemented the policies he criticized and to the people who were affected by them. The upshot was some of the most valuable public policy analysis you can read.

With PJ’s untimely death, those who were lucky enough to know him have lost an irreplaceable friend. Too few people realize it, but America has also lost an important public intellectual.