Education

The Maus That Roared

Maus was important to my life, but there's nothing wrong with protecting kids from encountering the world’s worst horrors before they are old enough to understand them.

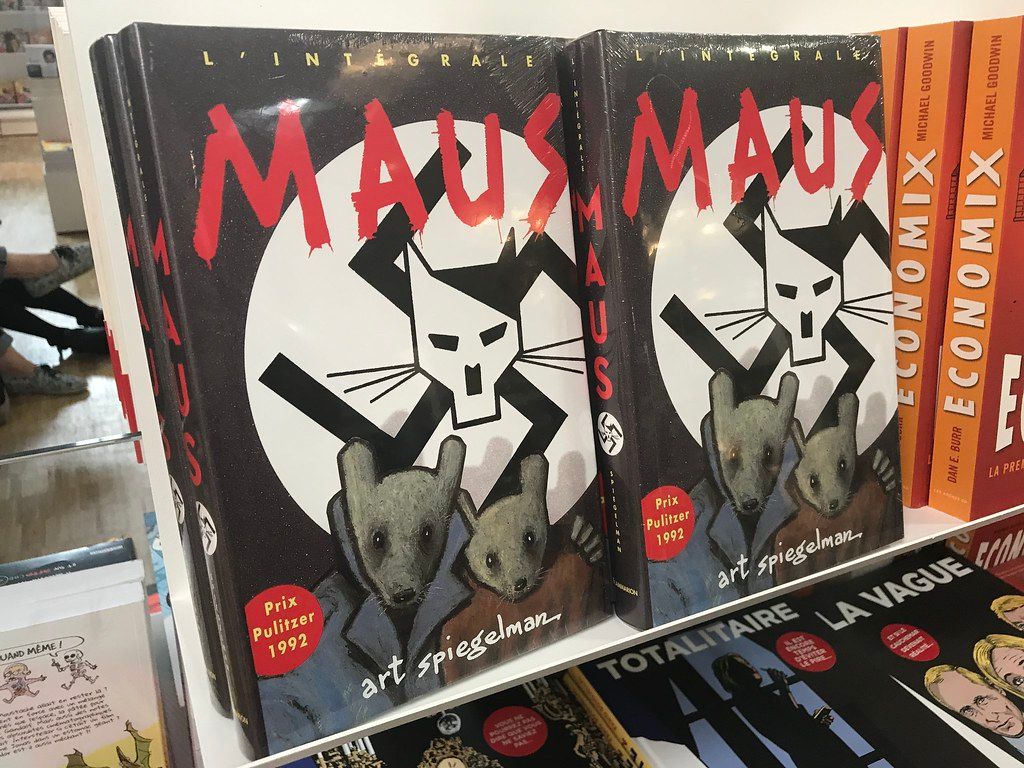

A lot of foolishness has been written about McMinn County’s decision to remove Maus from the middle-school Holocaust curriculum. Headlines from across the political spectrum bellowed that Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel had been “banned” and outraged commentary duly followed:

“There’s only one kind of people who would vote to ban Maus,” tweeted writer Neil Gaiman, “whatever they are calling themselves these days.”

“You can’t just swap out ‘Maus’ for another Holocaust book,” declared Jennifer Caplan in an op-ed for the Jewish Telegraph Agency. “It’s special.”

“I can virtually guarantee,” wrote Gregory Paul Silber in an open letter at comic culture webzine, the Beat, “that the vast majority of your 8th grade students have already heard worse than ‘goddamn’ and seen worse than nude cartoon mice.”

Even Spiegelman got in on the act. “The problem, of course,” he told CNN, “is that [this decision] has the breath of autocracy and fascism about it”:

“It has the breath of autocracy and fascism about it... I think of it as a harbinger of things to come.”

— Nora Neus (@noraneus) January 27, 2022

-Art Spiegelman, Pulitzer prize-winning author and illustrator of Maus, on a TN school district banning his book pic.twitter.com/C4IA7yQKFA

And so on.

First things first: Maus is not being “banned.” The McMinn County school board simply voted to remove it from the middle-school Holocaust curriculum. That’s not a ban, it’s a routine curriculum change. The Holocaust will continue to be taught, and Maus will be replaced with another text. Even if McMinn County removes Maus from the middle-school library (and it’s not clear they plan to do so), that still wouldn’t constitute a ban. They’re not saying kids can’t read it or that bookstores can’t sell it. They don’t have the power to ban Maus even if they wanted to. It’s freely available on the Internet to those who know where to look and can be found in nearly every library and bookstore in the country. No kid who wants a copy of Maus will have any problem getting their hands on it—even without the help of the great Maus giveaway this hysteria has inspired.

Caplan’s claim that the book deserves special treatment is also unpersuasive. It’s certainly true that Maus is a great book and that it was the first graphic novel ever to win a Pulitzer Prize. But that doesn’t mean it has to be in every middle-school classroom in the country. Madame Bovary is also a great book, but I wouldn’t include it on a list of required reading for teenagers. Other opponents of the decision argue that it’s just a comic book and that this medium has a unique appeal to kids. Well, I’ve taught comic books, including Maus, at the college level, and they are certainly not all suitable for children. Consider the work of Robert Crumb. Or Chester Brown’s controversial 2011 work, Paying for It: A Comic-Strip Memoir About Being a John. This is the genre of adult graphic novels and comics (sometimes called “comix”) from which Maus arose.

Early versions of Maus appeared in underground and alternative publications such as Funny Animals (1972), printed alongside stories like “Trots and Bonnie”—a tale “almost entirely about Bonnie's dog Trots fucking a poodle whore.” An early draft also appeared in Raw, a comic that billed itself as a “Graphix Magazine for damned intellectuals.” I’m doubtful there are many damned intellectuals in the McMinn County middle school, and I don’t mean that as a criticism. Raw, which was co-founded by Spiegelman, was clearly not intended for kids. Gregory Silber says he read Maus when he was 13 years old; Jennifer Caplan says she read it when she was 12. But that doesn’t necessarily make it suitable for all middle-schoolers in McMinn County. I didn’t read Maus until I was in my 20s, by which point I was mature enough to appreciate it. Had I encountered it a decade earlier, much of what makes it such a richly powerful work would have been lost on me.

More from the author.

There’s been a lot of eye-rolling about the board’s objections to the novel’s smattering of profanity (“damn” and “shit” both make an appearance) and its portrayal of “nude mice.” The latter point is particularly disingenuous for several reasons. First, Maus’s success and much of its power derive precisely from its depiction of Jews as “mice.” One can’t praise the ingenuity of that decision and trivialize it at the same time. Second, the drawings aren’t of mice, but of humans with mouse heads. Third, there are no “nudes” in Maus. There are, however, drawings of naked people with mouse heads being flogged across concentration camps and gassed to death. These drawings are neither aesthetic (in the manner of a classical sculpture or painting) nor prurient, they are meant to disturb. And, finally, there is at least one panel in Maus of a naked person who is not mouse-headed at all. That panel shows Spiegelman’s dead mother lying in a bathtub after she has overdosed on drugs and slit her wrists.

That harrowing image is included in the four-page insert “Prison on the Hell Planet” in volume I of Maus, and it is probably the strongest argument for questioning the age-appropriateness of the novel for middle school. In what one Goodreads reviewer calls a “claustrophobic, alienating and painful piece of graphic work,” Spiegelman relates how his mother committed suicide three months after he was released from a mental institution. Both the content and artwork in this section are difficult to absorb, not just because of the bathtub scene, but also because the expressionist illustrations are distorted and sometimes grotesque. At a time when teen suicide is at an all-time high, this section alone may have caused some parents and board members understandable concern.

And then, of course, there’s the devastating Holocaust imagery that includes piles of dead bodies, hanged men, and a child being smashed to death against a wall by a Nazi soldier. Whether it’s the murder of Jews, the death of his mother, the story of an affair Spiegelman’s father conducted before the war, the resentment the artist expresses toward his parents, his father’s toxic second marriage, or the stark black-and-white drawings, the whole tone and tenor of the novel is adult. Does this mean young teenagers shouldn’t be allowed to read Maus? No, of course not. It does mean, however, that it’s not completely unreasonable for a parent or educator to reserve this book for older readers who will be better placed to understand and appreciate its importance and value.

But this is real life, people say, and kids have to learn that this is the way the world is. As a second-generation Holocaust survivor myself, this is an impulse I understand. I, too, have experienced periods when I wanted to wreck the world’s innocence because of what my family went through. But it is also an impulse to which Spiegelman himself offers a subtle rebuke in the very first pages of Maus. As a young boy, Spiegelman runs home in tears when his friends abandon him after a skating accident. “Friends? Your Friends?” his father says bitterly when confronted with his distraught son. “If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week ... then you could see what is friends!” This vignette illustrates how survivors’ trauma can be passed from one generation to the next.

It’s the only explanation I can think of for Spiegelman’s apoplectic loss of perspective on this issue: You want to protect kids from the world? Let me tell you something about the world. But it’s not wise or fair, as Spiegelman himself implies in his own novel, to force others to confront the horrors we have experienced before they are ready. I find Spiegelman’s lack of self-awareness on this point disturbing. “I also understand that Tennessee is obviously demented,” he has said in an interview. What sort of writer accuses people of being demented for not compelling their children to read his book?

And “compelling,” by the way, is what curricula do. A more honest headline than “School Board bans Maus” would be “School Board will no longer force students to read Maus.” Maus is an important book. It was important in my life. But it is not the sine qua non of Holocaust literature. You can’t say that of any single book with the possible exception of The Diary of Anne Frank. Even if Maus were indispensable, there’s no reasonable way to argue that it must be taught before kids get to high school.

Yes, it is true, as Silber and others have pointed out, that kids see and hear profanity all the time on social media and elsewhere. Most of them already have access to pornography. But that doesn’t mean that schools have to welcome TikTok or profanity (or pornography, for that matter) into their middle-school classrooms. On the contrary, maybe schools should be a sanctuary from such influences for that very reason. My son is 13, and we don’t let him listen to explicit songs on Spotify even though we know he can hear them elsewhere. We can’t protect him from all exposure, but we can at least create a space in our home where he is free from such things. A school board may, likewise, decide to circumscribe the content that kids encounter in school. Which is not to say that Maus is pornographic. It clearly isn’t. But the fact that kids are already exposed to pornography doesn’t mean we have to expose them to less graphic but still potentially disturbing content, even in the name of Holocaust education.

I’m a writer. I’m an English Professor. I’m a comic-book lover. I’m a Jew and a second-generation Holocaust survivor. I understand perfectly why Maus is great. It was important in my life. It helped me to understand my father, who was a lot like Spiegelman’s. That doesn’t mean I get to insist that every county in the country include the book in their eighth-grade Holocaust program. I don’t know the kids in McMinn County, but I doubt they’ll become Nazis because they didn’t get to read Maus until ninth grade. Nor will they become degenerates if they read it in seventh grade. But it’s not my call (or yours) unless you live in that county, and it’s certainly not antisemitic or book-burning to replace one Holocaust text with another. Even on International Holocaust Day. Even if it’s Maus.

So, why all the weeping and gnashing of teeth? Some elements on the Left clearly want to use this issue in order to discredit recent parental efforts to remove inflammatory texts about race or explicit sex education materials from school curricula. It’s all part of “the right’s obsession with education,” argues Sarah Jones in New York magazine. “Maus is just the tip of the iceberg,” writes Amanda Marcotte in Salon. You can almost hear these writers intoning, First, they came for LGBTQ literature in the schools and I did nothing ... We should be wary of those who use accusations of antisemitism to rally others to their political causes. The debates about CRT and sexually explicit graphic novels have nothing to do with Jews or the Holocaust, and there’s something cynical and exploitative about political attempts to link these controversies.

Would I replace Maus on a middle-school curriculum if it were up to me? At first, I wasn’t sure, but after re-reading the book last night, I think I probably would. I suspect a lot of kids who are not Jewish may be put off by the style and the content, and I’m confident that a lot of it will simply go over their heads. My wife and I haven’t yet given it to our middle-school son to read, and he’s a third-generation Holocaust survivor from both sides. I wouldn’t prevent him from reading it now. And I expect he will read it some day. But he doesn’t have to read it yet.

Even if we disagree with the board’s decision because we believe the book’s power and value outweigh its concerns, that doesn’t mean the board is irrational or hateful or promoting ignorance. They simply want to protect kids from encountering the world’s worst horrors before they are old enough to understand them. And there is nothing sinister or bigoted about that.