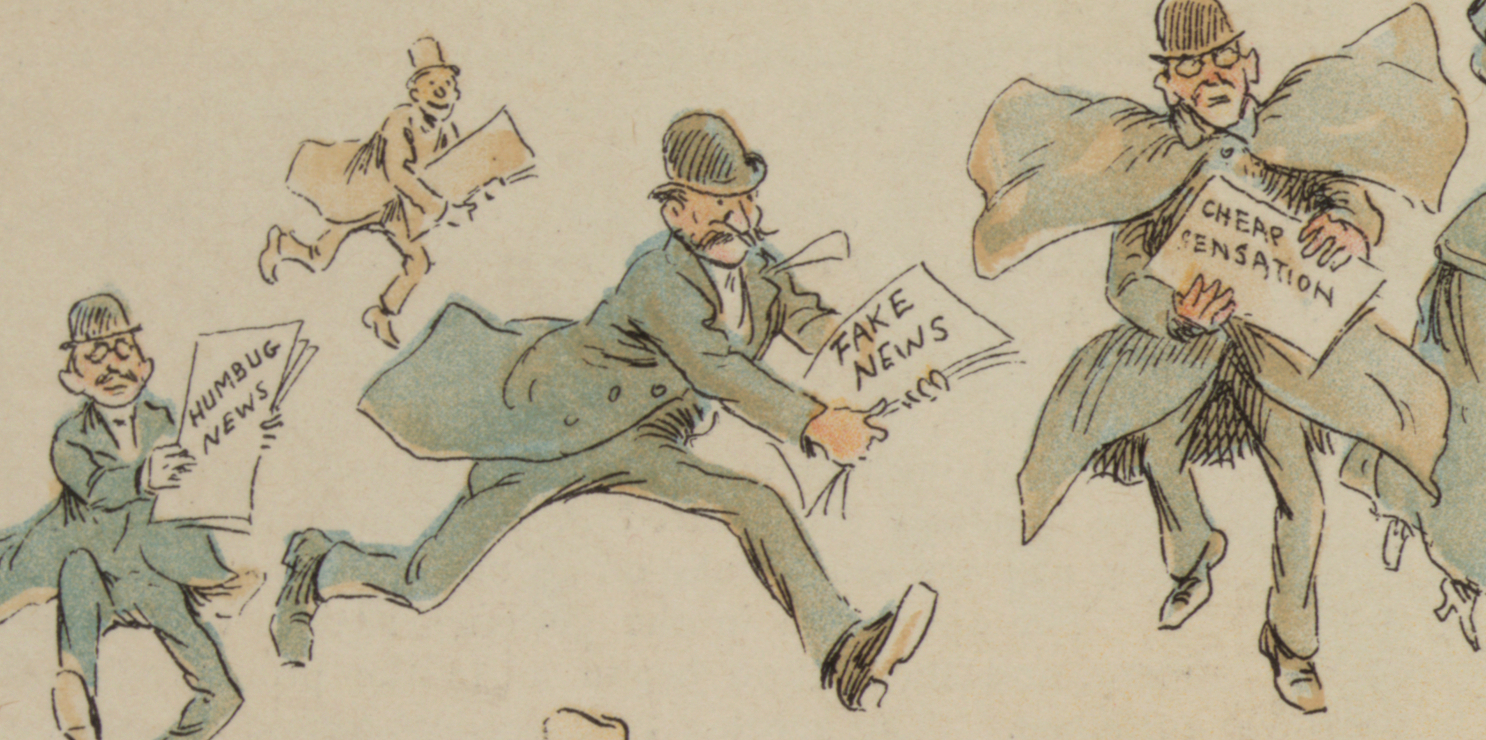

Bitter Fruit: Marshall McLuhan and the Rise of Fake News

McLuhan’s phenomenal success stemmed from being in the right place at the right time.

In Orson Welles’s classic movie Citizen Kane, the eponymous hero publishes a statement of principles on the front page of his newspaper, “I’ll provide the people of this city with a daily paper that will tell all the news honestly. ... They're going to get the truth from the Enquirer, quickly and simply and entertainingly and no special interests are going to be allowed to interfere with that truth.” It is a promise that Kane, a character loosely based on the press baron William Randolph Hearst, ultimately breaks. Today, the point Welles was trying to make is easily misunderstood. The movie is not being cynical about journalism, nor about the goal of searching for truth. Kane's tragedy is that he falls short of his noble ideals. The movie was therefore acknowledging the contract that existed between journalists and their audiences during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was the expectation that journalists ought to search for, and report, the truth.

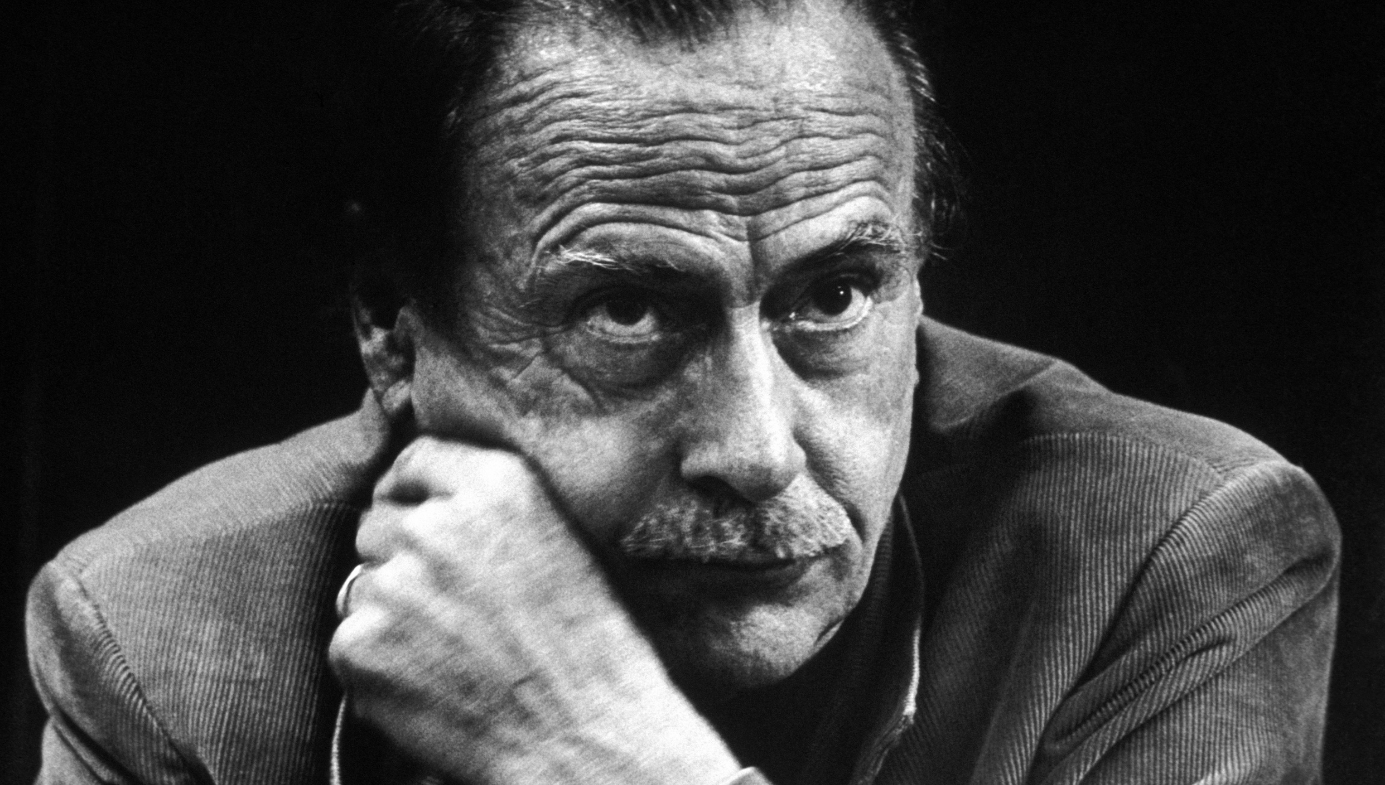

We have travelled a long way since then. The media ecosystem of the early 21st century is marked by a collapse of trust in journalism. How did we get here? As we look back, like a detective searching for clues, one moment stands out as significant; the publication on March 1st, 1962, of The Gutenberg Galaxy, written by a then-obscure Canadian academic named Marshall McLuhan. This book set in motion a line of falling dominoes, the consequences of which continue to affect us profoundly today.

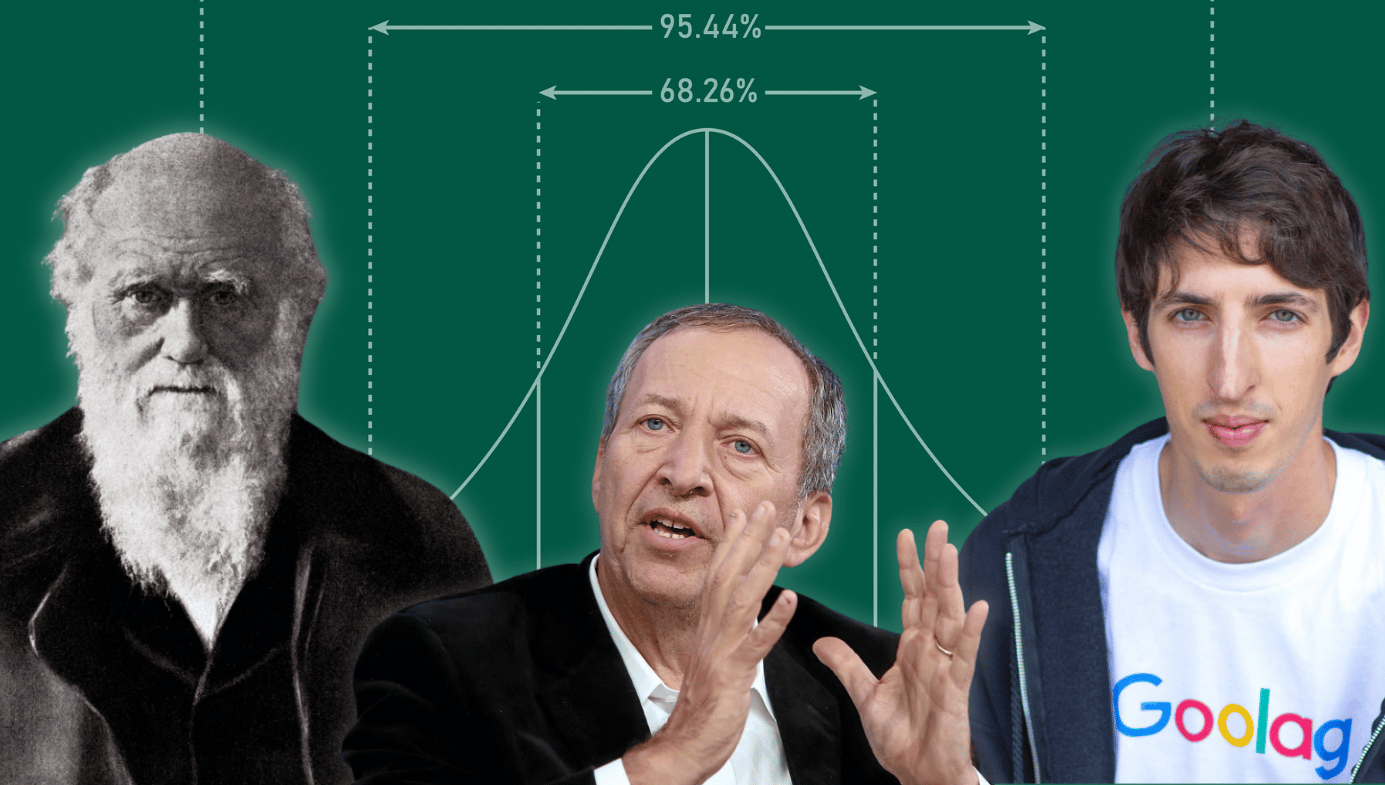

McLuhan came to be regarded by the Baby Boomer generation as a guru and prophet; a visionary who had discovered something profound, not merely about the media, but about life and the universe. During the 1960s, he became a major celebrity, especially in the US. He featured on the cover of Newsweek magazine, was frequently interviewed on TV, and made a cameo appearance in Woody Allen’s 1977 movie Annie Hall. There was even a prog rock band named in his honor. The American media historian Aniko Bodroghkozy writes that “no other figure who was not of the movement itself received so much positive notice in the alternative newspapers that served dissident youth communities.” In 1965, the celebrity journalist Tom Wolfe asked breathlessly, “Suppose he is what he sounds like, the most important thinker since Newton, Darwin, Freud, Einstein, Pavlov?” Wolfe described McLuhan as an almost Christ-like figure:

A lot of McLuhanites have started speaking of him as a prophet. It is only partly his visions of the future. It is more his extraordinary attitude, his demeanor, his qualities of monomania, of mission. He doesn't debate other scholars, much less TV executives. He is not competing for status; he is alone on a vast unseen terrain, the walker through walls, the X-ray eye.

Writing in 1967, John Quirk agreed that McLuhan was a “savant and prophet” and explained that, “McLuhanites hold that the new technologies will lend men the awareness and instruments necessary to solve contemporary problems and inaugurate a bright new era.” McLuhan was a master of the catchy one-liner and the original source of Timothy Leary’s famous counterculture catchphrase, “Turn on, tune in, drop out.” Writing in the underground paper the Spectator in 1969, Ken Rogers described McLuhan as “one of the twentieth century’s most important thinkers,” whose ideas would help the Boomer generation change the world and make it a better place:

It is only by rejecting the conventional wisdom, to the extent of at least opening our minds to radically different possibilities, that we are going to effect any lasting beneficial change in our circumstances. To think freely, imaginatively, change-fully, we must willingly suspend our “common-sense,” and seriously play with new ways of looking at things. ... McLuhan's book provides such an opportunity for expanded awareness.

Another underground paper, IKON, went further. Its October 1967 edition announced that McLuhan’s theories justified the belief that the Boomers were the first of a higher type of being capable of bringing about a new Utopian age:

Djwhal Khul states that telepathy will become normal in 500 years while McLuhan discusses the total extension of consciousness to be brought about by the use of electric technology. The Aquarian Age is an era of peace and brotherhood; McLuhan foresees through electricity; global unity, universal understanding, collective peace and harmony.

McLuhan’s impact on journalism was significant. His message was that all the techniques and values of Victorian liberal journalism should be discarded. The old-fashioned search for truth, using the tools of balance, objectivity, and impartiality, no longer applied. Although greeted with indifference or derision by older journalists, McLuhan's insight was a Damascene moment for many young writers. As one underground journalist explained in 1966:

One year ago, in the first issue of The Paper, I discussed the loyalty I felt I had to the traditional ideals of journalism. ... In the year since we began publishing, a very significant evolution has taken place in and around the American press.

The writer adds that he attributes “a great deal of importance to McLuhan” who had been his guide on a journey of transformation and enabled him to abandon the old journalism: “[W]e really didn't have the slightest idea what we were getting into last year, when we thought we cared mainly about journalistic ideals.” Having abandoned impartiality, the writer describes how he embraced “the tendency to enlightened and interpretative subjectivity.” By being less accurate and more subjective, the writer concludes that his journalism is now successfully “portraying a more accurate, objective picture of the action of our time than can be given through the use of linear-objective, formula journalism.” What would have seemed ridiculous and irrational only a year earlier, had become legitimate thanks in no small part to McLuhan’s theories.

McLuhan's doctrine was attractive to the Boomers because it explained that everything the older generation knew, or thought they knew, was an illusion. Everything the Boomer tribe intuitively felt, on the other hand, was real. It was a doctrine of fantasy and truthophobia consciously designed to appeal to the Boomers’ generational vanity. As Bodroghkozy remarks, McLuhan enjoyed his celebrity status and played to the gallery:

McLuhan was a weapon. An establishment-sanctioned and respected professor, McLuhan’s theories—as mobilized by the youth movement—damned their elders and the entire established social system while praising insurgent youth culture and youth values as the inevitable wave of the future.

Yet, McLuhan was an unlikely hero for the swinging ‘60s. He was brought up a Baptist before converting to Catholicism. The result was a form of religious belief which combined an intense personal faith with a longing for harmony and order. As McLuhan’s biographer Douglas Coupland explains:

He went to Mass almost daily every day for the rest of his life. He recited the rosary. He was a firm believer in Hell. He was disgusted that other Catholics weren’t Catholic enough.

McLuhan longed for the certainty that only faith can bring. He once told a friend he could know things with certitude and without recourse to evidence. When asked how this was possible, he replied matter-of-factly, “I know this because the Blessed Virgin Mary told me.” McLuhan also had a rare cerebrovascular disorder which affected his brain function and his perception of material reality. According to Coupland, he “exhibited throughout his life a certain sense of obliviousness about the physical world.” His condition also left him susceptible to blackouts and strokes. In 1967, he underwent brain surgery and suffered “countless small strokes during his lifetime—sometimes in front of a classroom of students, where he’d suddenly gap out for a few minutes and then return to the world.”

Although McLuhan rarely discussed his political views in any detail, one of his early works expressed admiration for Mussolini’s fascist regime. His 1934 article “Is Fascism the Answer?” describes fascism as the “common recognition of human brotherhood,” and favorably contrasts it with the mere “parliamentarism” of Victorian liberal democracy which, he complains, has become “a mass of nonsense” and a mess of “confusing issues and party politics.” He wonders whether “parliamentarism might be purged and saved,” but rejects this in favor of fascism, which encourages citizens to “unselfishness, honor and efficiency.” McLuhan ends his article by praising fascism’s clarity, purity, and efficiency: “[T]he amazing thing about a system that looks so good on paper is that it has produced results that are entirely amazing.”

By the 1960s, McLuhan had perfected a highly eccentric style of writing. He referred to it as a “mosaic,” and to his paragraphs as “probes.” Instead of trying to produce a coherent, rational thesis, he aimed to produce works that were low in reasoned argument, but capable of influencing and persuading through rhetorical and poetic devices. Abstruse, gnomic sentences, rich in puns, ambiguities, and paradoxes, invited readers to endlessly interpret and add their own meanings. His style became known as “McLuhanese” and attracted much wry comment from critics. As the American author Sidney Finkelstein quipped in 1967, “A magazine cartoon shows a store with a sign in the window, ‘McLuhanese spoken here.’”

In The Gutenberg Galaxy, McLuhan observed that the decline of Catholicism, the rise of Protestantism, and the drift towards secularism all coincided with the development of printing. He hypothesized that the invention of printing had produced the European Enlightenment and Victorian liberal democracy. It was not what was printed, but printing itself that was responsible. McLuhan classified all media into two types: “hot” and “cool.” Printed books and newspapers, he suggested, were “hot” because they were bursting with information. Pre-Renaissance forms of communication, on the other hand, like the spoken Catholic Mass, were “cool.” This was because the Mass was spoken in Latin and hence contained little or no information that ordinary people could understand. Handwritten books were also categorized as “cool.”

Print, therefore, according to McLuhan, was an unnatural, alien invader: “Print was, that is to say, a very ‘hot’ medium coming into a world that for thousands of years had been served by the ‘cool’ medium of script.” TV, said McLuhan, was a “cool” medium which meant that humanity was today returning to a more natural and familiar epoch:

[The] human family now exists under conditions of a “global village.” We live in a single constricted space resonant with tribal drums … once more any Western child today grows up in this kind of magical repetitive world as he hears advertisements on radio and TV.

McLuhan argued that the Boomers were the first generation since the 16th century whose worldview and way of knowing were shaped by a cool medium. This explained why they rejected the worldview of their parents. Suckled on cool media, they were innately hostile to reason, logic, and fact, and predisposed to medieval, religious ways of knowing based on emotion and shared tribal intuition. From this, McLuhan concludes that the informational content of a message should be disregarded because it was an illusion. Like the indistinct chant of a Latin Mass in a 14th century cathedral, it was not the individual words that had meaning, but the totality of the experience that mattered—the noise, the smell of incense, the desire to believe. What presented itself as factual content was merely a theatrical flourish, a dramatic sound effect or a puff of smoke in a magician's performance.

McLuhan used The Gutenberg Galaxy to test his ideas, but its numerous references to Catholicism and theology prevented it from becoming a bestseller. It was McLuhan's next book, Understanding Media, that catapulted him to fame. In it, he restated his original thesis, that the factual content of a message was like “the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind,” but this time he shrewdly removed all mention of the Church.

What remained was a secular-mystical account of media with numerous oblique spiritual and metaphysical allusions. He had produced a Boomer-friendly, sanitized version of his thesis in which magic and fantasy replaced religion. He also took care to flatter his Boomer audience by telling them that they were uniquely in tune with a deeper reality their parents could not see or understand. “We of the TV age,” he wrote, “are cool. The waltz was a hot, fast mechanical dance suited to the industrial time in its moods of pomp and circumstance. In contrast, the Twist is a cool, involved and chatty form of improvised gesture.”

McLuhan told the Boomers that they might appear irrational to their parents, but this was simply because the old generation was raised on obsolete “hot” media. As a result, he said, they had lost touch with their emotional side and become unnaturally rational and impartial: “Phonetic culture endows men with the means of repressing their feelings and emotions when engaged in action. To act without reacting, without involvement, is the peculiar advantage of Western literate man.”

Fortunately, McLuhan says, we have now returned to a “cool” age with a superior way of knowing; “the state of tribal man,” for whom magic rituals are his means of “applied knowledge.” Those who disagree with this thesis are attacked as idiots “no longer relevant to our electric world.” Try as he might, however, McLuhan could not avoid theology. The best he could do was disguise religion by introducing “electric light” as a synonym for God. “The electric light,” he wrote, “is pure information. It is a medium without a message...”:

It is pure information without any content to restrict its transforming and informing power. If the student of media will but meditate on the power of this medium of electric light to transform every structure of time and space and work and society that it penetrates or contacts, he will have the key to the form of the power that is in all media to reshape any lives that they touch.

Electric light, he concludes, has the power to lead us to a “moment of truth and revelation from which new form is born.” According to McLuhan, the truths of journalism are a poor substitute for cosmic Truth. The uncertainties of the material world described by journalists in their impartial reports were feeble, transitory things. Hence, McLuhan’s contempt for Victorian liberal journalism was also an expression of the superiority of God’s way of knowing. As he put it in one of his posthumous works, The Book of Probes, in the merely secular world, “all media exist to invest our lives with artificial perception and arbitrary values.”

Understanding Media contains many scornful and mocking references to traditional journalism, all of which suggest that news is a form of theatre or masquerade that constructs an artificial reality:

Today's press agent regards the newspaper as a ventriloquist does his dummy. He can make it say what he wants. He looks on it as a painter does his palette and tubes of pigment; from the endless resources of available events, an endless variety of managed mosaic effects can be attained.

Journalists, says McLuhan, are incapable of seeing that their techniques of objectivity and impartiality are useless because we have entered the electric age. News reports that “present a fixed point of view on a single plane of perspective, represent a failure to see the form of the press at all. It is as if the public were suddenly to demand that department stores have only one department.” He proclaims that all journalism is, in fact, fiction:

Fairly soon the press began to sense that news was not only to be reported but also gathered, and, indeed, to be made. … Thus “making the news,” like “making good,” implies a world of actions and fictions alike. But the press is a daily action and fiction or thing made.

The consequence of this doctrine for journalism was profound and the Boomers were quick to see it. Journalism was a web of fiction; in the words of Shakespeare, it was a tale “told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.” McLuhan’s doctrine was not merely destructive of the authority of journalism, it also undermined liberal democracy because it preached that the information required by citizens to make rational choices did not exist. If McLuhan longed for a pre-modern spiritual world, he also longed for a pre-democratic political world.

McLuhan is best remembered for his shortest, most visually appealing book, The Medium is the Massage [sic], which appeared in 1967 and sold more than a million copies.

It looked like a comic or graphic novel—a mosaic of McLuhanese textual “probes” inter-cut with surreal images produced by the graphic designer Quentin Fiore. There was nothing new in the book; McLuhan merely recycled his argument that the values of old-school journalism could no longer apply in a cool world of electric media: “Societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media by which men communicate than by the content of the communication … the older training of observation has become quite irrelevant in this new time.”

The book features lavish flattery of the Boomers, whom he portrays as struggling nobly to overcome obstacles imposed on them by an obsolete “hot” worldview. Today’s television child, says McLuhan, is “bewildered when he enters the nineteenth century environment that still characterizes the educational establishment.” And, “The young today live mythically and in depth … many of our institutions suppress all the natural direct experience of youth. … The dropout represents a rejection of nineteenth century technology.”

The book ends with a thinly veiled attack on Protestant theology and the Enlightenment. McLuhan has judged it, pronounced it guilty, and sentenced it to death: “The Newtonian God—the God who made a clock-like universe, wound it and withdrew—died a long time ago … [it is] the Newtonian universe which is dead. The groundrule of that universe, upon which so much of our Western world is built, has dissolved.”

McLuhan's reputation remains high with the Boomer generation, but his arguments have not aged well and do not survive critical scrutiny. McLuhan offers evidence-free explanations that only make sense if one already believes them. The first step must be taken in faith, and after that step is taken, everything that follows falls into place. To paraphrase Saint Augustine, “If you would believe in McLuhan, look within. And the answer comes—McLuhan, I believe.”

Disbelievers, however, accused McLuhan of being a celebrity-seeking charlatan. Sidney Finkelstein described Understanding Media as “generalized nonsense,” full of wild assertions and historical errors:

A perfectly apt foreword to the book would be: “No statements in this book are necessarily to be taken as true. The author is not concerned with whether they are true or not. Any agreement between what this book says about history, and what happened in history, is purely coincidental. The statements are only probes of the reader’s mind.”

Finkelstein also objected to the implication that humans are intellectual zombies whose beliefs are determined by the type of media to which they are exposed. McLuhan, he said, denied individual agency and peddled a depressing doctrine of tribal conformity and collectivism:

He omits entirely the creative human spirit, the great human conquests of obstacles and problems, the visions and bold transformations of the world, the daring explorations of reality, the battles of ideas. In McLuhan’s history, the human being dwindles to almost nothing.

The media critic James Carey was quick to spot the disguised theology, pointing out that, for McLuhan, the medium was a sacred object. He pointed out the obvious longing to return to a simpler, purer age: “[T]he vision of the oral tradition and the tribal society is a substitute Eden, a romantic but unsupportable vision of the past. What McLuhan is constructing, then, is a modern myth.” Carey also attacked McLuhanese, arguing that McLuhan had put himself beyond criticism because “his work does not lend itself to critical commentary. It is a mixture of whimsy, pun, and innuendo. These things are all right in themselves, but unfortunately one cannot tell what he is serious about and what is mere whimsy.”

Trying to deconstruct McLuhan’s arguments reveals glaring absurdities. For example, it is self-defeating to claim that the content of a message is unimportant. On the contrary, all messages must convey information which corresponds with, or claims to correspond with, some state of affairs in the real world if they are to be useful. A news article without news, a weather forecast that does not mention the weather, or a traffic report lacking information about traffic might all be deliciously McLuhanesque, but they are not helpful. Even the Bible, revered by McLuhan, would be meaningless if it were merely a book of random words and blank pages. As Finklestein summarized, McLuhan’s argument is “absurd, when analyzed."

McLuhan's approach is philosophically very similar to that of the French postmodern theorist, Michel Foucault. Foucault, who is better known in the UK and Europe than McLuhan, argued that people from different historical ages have different worldviews, beliefs, and assumptions. Thus, people from different “epistemes” are trapped in different “regimes of truth.” The Foucauldian approach sees human knowledge as constructed by history. McLuhan sees human knowledge as something constructed by the media that history produces. It was to escape this epistemic relativism that the thinkers of the Enlightenment turned to objective notions of scientific truth based on evidence. Thus, to the McLuhanite/Foucauldian assertion that different eras construct different narratives in which they are confined, the empiricist replies, “Yes, but which narrative is true?” Perhaps it is significant that McLuhan and Foucault shared both a Catholic faith and a nostalgia to return to the certainties of the pre-modern, pre-Reformation era.

McLuhan’s way of knowing is truthophobic because it bypasses epistemology entirely. According to McLuhan, the belief that human beings make informed evidence-based judgments about what is true and false is an illusion caused by the invention of printing. But McLuhan was not interested in this sort of truth, nor this sort of reality. What obsessed him was the transcendent, sweeter, more perfect reality to come. As the American cultural critic Nicholas Carr points out, “What lay in store, McLuhan believed, was the timelessness of eternity. The earthly conceptions of past, present, and future were, by comparison, of little consequence.” Or, as McLuhan put it in another posthumously published book, The Medium and the Light, “In Jesus Christ, there is no distance or separation between the medium and the message: it is the one case where we can say that the medium and the message are fully one and the same.”

McLuhan’s phenomenal success stemmed from being in the right place at the right time. His hip, gnomic writing struck a chord with the Baby Boomer generation. He legitimized what the Boomers intuitively felt—that they were morally and intellectually better than their parents. As a bonus, his deterministic doctrine cancelled the notion of personal responsibility. The thoughts and impulses of the Boomers were simply constructs of the electric age. To question them was futile and ignorant. McLuhan offered the children of the TV age an alternative way of knowing and being; one based on intuition and shared tribal fantasy, and the Boomers relished the message.

McLuhan taught the Boomers that journalism was not a source of truth, but an instrument to help them get what they wanted. He preached that young people did not have to accept the reality described by journalists. Instead, they could construct their own. And so, journalism became indistinguishable from propaganda. Danny Goldberg, a fan of McLuhan during the 1960s, interpreted his hero’s message as follows: “The media was an indispensable tool for social change. It was certainly what got to me as a teenager.”

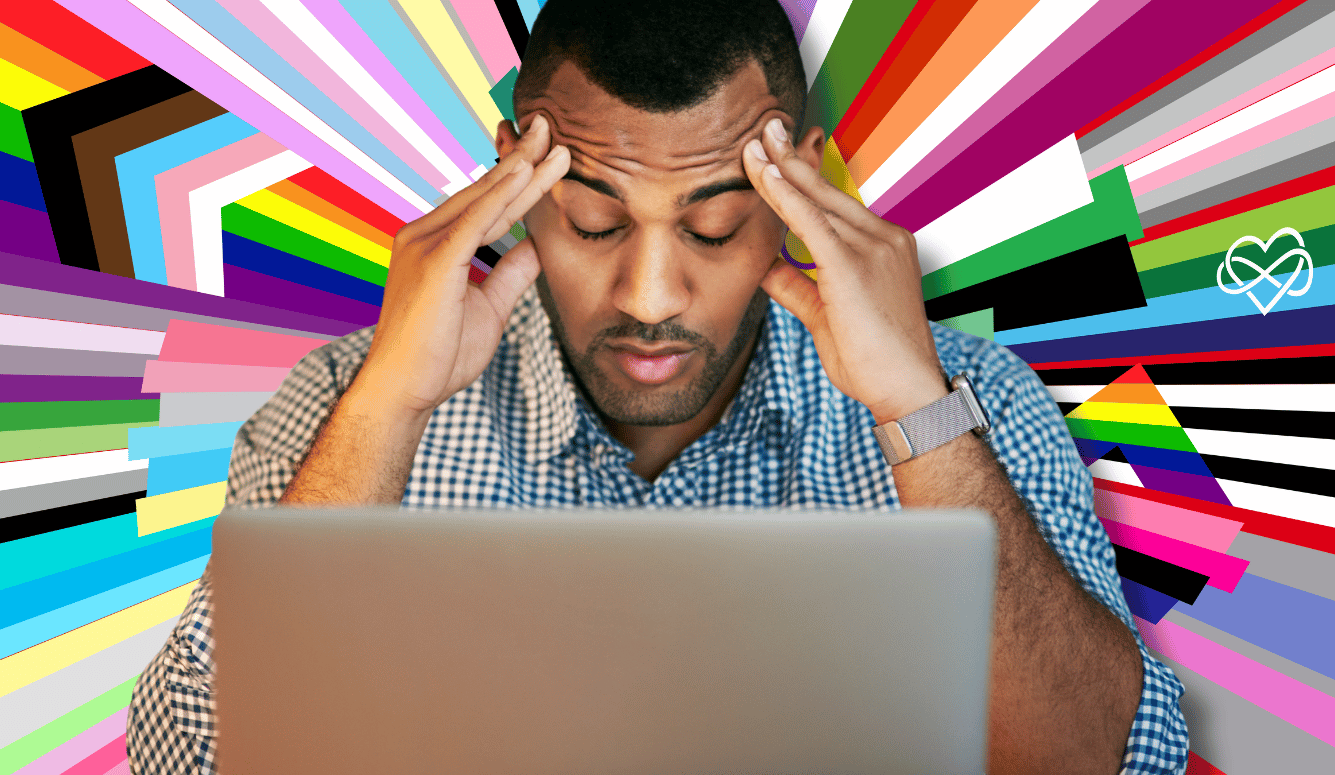

McLuhan shared with the Boomers a longing for something better than the imperfect version of truth found in the newspapers and on the TV screens of the 1950s and ’60s. An unforeseen consequence is that, 60 years later, we live in a divided society. Rival tribes, sealed in their own bubbles of information and certainty, are today unable to talk to each other. Climate change believers and climate change deniers, pro-vaxxers and anti-vaxxers, Democrats and Republicans all trade insults, abuse, and threats on social media. Each tribe has its own journalism and its own preferred set of narratives. Each rejects the journalism of the other as misinformation, fake news, lies, or hate speech. McLuhan’s search for perfection did not turn out quite the way he envisaged. What grew out of the rubble of the old journalism was not a garden of beautiful flowers, but a tangle of thorny weeds bearing a harvest of bitter fruit.