Conspiracy Theories

An Outback Conspiracy

Misinformation results from the toxic combination of these two defining features, a lack of proximity to the Territory, and viewing the world through the lens of oppression.

We knew that it was probably inevitable. The coronavirus has leapt out of its urban cage into remote indigenous communities in Australia’s Northern Territory. Within the last fortnight, the virus emerged first in the small township of Katherine, then in the Aboriginal camps of Robinson River, Binjari, and Rockhole. Perched in the lightly treed country between the sets of classic films like Crocodile Dundee and We of the Never Never, these communities barely contain more than a few hundred people each and are as unknown to most Australians as they are to most Americans. How strange it is then that these small geographically isolated communities should be the center of social media conspiracy theories across the oceans.

The context is essential. Indigenous people suffer a significantly higher degree of many diseases that make comorbidity with COVID-19 much more than flu. The social environment of indigenous people is often extremely communal and mobile, with intermingling occurring all day across homes and camps. To compound matters, these communities have lower than average vaccination rates against the virus. This is why the Jawoyn, Wardaman, Mialli, and other indigenous groups that converge in the Katherine region have been among Australia’s most protected groups throughout the pandemic. Strict border controls to the Territory have up until now prevented transmission. Despite these stringent precautions, the Territory government has long presided over what it knows to be a powder keg, watching and waiting for the first spark to ignite. The spark has now been lit. Scrambling to lock down these communities, provide food, test for COVID, and vaccinate is now the Territory’s mission. Its goal: drive the virus back down to non-existence until vaccination rates increase. To bolster the Territory’s efforts, the Australian Defence Force has put members at their disposal to help with the food and transport logistics.

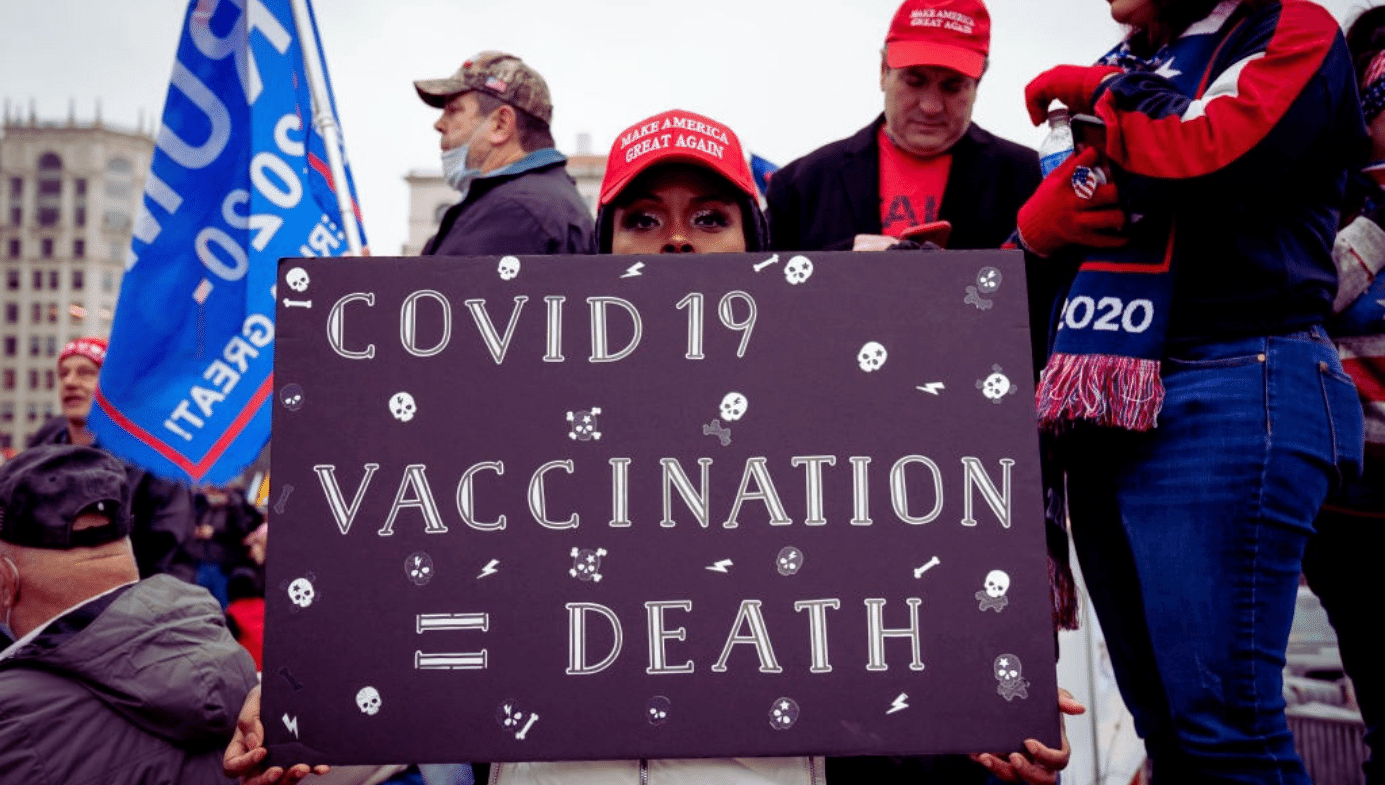

The lockdown of these communities in the past weeks hasn’t been without its hiccups. Some homes running on prepaid power cards have run out of credit, leaving homes temporarily without power before the government could resupply them with more power cards. But if we are to believe a sleuth of social media and YouTube commentary, things are a lot worse than that. “There are all kinds of reports all over the internet of Aboriginal people being chased down, hunted down like wild animals by their own government, by their military,” beams American commentator Stew Peters on his online Stew Peters Show, “Kids are being chased by the military personnel, tackled to the ground, pinned down and forced jabbed with syringes … They’re being chased down in the bush in the wild there like animals and injected.” American YouTube personality Tim Pool has taken to Twitter to raise specters of the Holocaust. Over a series of tweets this past week, Pool has blamed military trucks in Katherine for “shipping” people to “concentration camps,” referring to Howard Springs Quarantine Facility where some people have been isolated.

"authorities had identified 38 close contacts in Binjari — a number he said was likely to rise — who were transported to Howard Springs on Sunday."

— Tim Pool (@Timcast) November 22, 2021

So, the Asutralian army is now shipping people to concentration camps for contact with someone with COVID?https://t.co/CCr1AwB9vB

He has blamed Australians for their acquiescence in “forcefully relocating” indigenous people and has stamped one online magazine editor (I won’t say which one) a “Nazi” for not speaking out. Thousands of social media commentators decry “crimes against humanity” in the Territory, calling for “foreign intervention.” Some have even drawn allusions to the Stolen Generation, the forced removal of children from their Aboriginal parents in Australia’s past, and have suggested the same is happening now.

Dealing with conspiracy theorists can be frustrating at the best of times. But there’s a special kind of provocation experienced when you have insider knowledge that puts you in a different epistemic position altogether from the conspiracist. As an Australian, I don’t know what to make of the conspiracy theory that Australia doesn’t exist and that tourists journeying to Australia are just taken to “parts of South America, where they have cleared space and hired actors to act out as real Australians.” If this is true, I need to speak to someone because I haven’t seen a dime of that acting money yet. From the inside, some conspiracy theories look very stupid. So for me, a social welfare worker living in the Katherine area in an organization assisting indigenous clients, this is one of those rare times that a conspiracy theory debunks itself.

There’s no army here holding people down and vaccinating them against their will. Nobody is being rounded up at the point of a gun. The army is not even carrying guns. If my word alone isn’t good enough, you’ll have to go quite deep down the rabbit hole to deny what Aboriginal leaders themselves have come forward to tell the media in the past few days.

“The Covid team working in my community at the moment is best for my community, my people,” indigenous Garawa leader Dickie Dixon said a few days back about Robinson River. However, it’s true that the indigenous community didn’t simply roll up their sleeves at the sight of health workers. “We sat down with the health team that came around and gave us the info of what’s coming and how you can get the vaccine,” said Dixon, “We questioned everything, but we still got it.”

“We are very pleased with how the Northern Territory Government has reacted to the outbreaks in Katherine and Robinson River,” confirms a press release of the Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance Northern Territory, an Aboriginal controlled body seeking to improve culturally appropriate medical care for indigenous people in the Territory. “Northern Territory Government staff have gone above and beyond to protect our people and we thank them all sincerely.”

Some people here in the Katherine area aren’t even aware of the conspiracy theories taking shape on social media overseas about our communities. “This is the first time I heard that, when I happened to be watching TikTok this morning,” the Kunwinjku man Andy Garnarrandj told Australia’s National Indigenous Television network. “It’s not happening here.” Residents of Binjari troubled with social media hysteria have spoken through the Wurli-Wurlinjang Aboriginal Health Service to the media from their locked-down community. In the words of one Binjari woman, “I wanna say after seeing all the social media stories saying things about Binjari communities and the lockdown … The army and police are not removing anyone against their will. There are no children getting forcibly vaccinated.” “We are being looked after and have a voice to people that can answer our issues,” another Binjari woman says in admiration for health workers, “All the workers are working hard in the heat in their suits and we know it’s not easy.”

“We are in the biggest fight of our lives,” community leaders in Binjari and Rockhole camps announced. In an expression of their gratefulness to health workers, the leaders said, “We have been treated with a lot of respect and appreciate all the support being given by these support personnel people.”

Please share. From the Traditional Owners of Binajri and Rockhole#covid #nt #aboriginal #katherine #binjari #rockhole pic.twitter.com/xBvRmBx4EB

— Luke Ellis (@lukeae88) November 24, 2021

“People are being treated with respect and nobody is being held down and forced to be given the COVID-19 vaccination,” the well-known Aboriginal town councillor Jacinta Nampijinpa Price said in a recent Facebook video. Known as a conservative voice in Australian politics and an opponent of vaccine mandates, Price has nonetheless ridiculed the claims made as deeply disrespectful, “Likening it to Stolen Generations is an insult.” Wurli-Wurlinjang Aboriginal Health Service’s Luke Ellis tweets from quarantine, “My grandmother was stolen generation. To compare what I’m going though in this camp to what she and her generation went through is disgusting.”

The camp Ellis speaks of is the Howard Springs Quarantine Facility, where he and 39 other indigenous people from these areas have been taken to isolate for two weeks. This is Tim Pool’s “concentration camp,” the same one that interns international arrivals including our National Olympians.

This is not America. I want you to understand that. In communities like Binjari there are upwards of thirty people living under a single house roof. That makes a mockery of the idea of self-isolation at home. So when the government realized that 39 people were probable infections, they were transferred, without protest, to Howard Springs. Of these, all 39 have tested positive, meaning that hundreds of indigenous people in their households have been spared infection.

Now, think what you will about the defining criteria of a concentration camp, but my reading of Viktor Frankl’s description of his time in Auschwitz and other camps in Man’s Search for Meaning leaves a somewhat different impression. Let Frankl tell you what a concentration camp is. It’s being stripped naked. It’s taking beatings for no good reason at all. It’s trying not to make eye contact with guards. It’s being crammed together and forced to sit on feces and urine. It’s endless forced labor in snow. It’s the sound of sulking from a grown man whose swollen feet won’t fit into his shoes. It’s the slow, drawn-out process of starvation. It’s the moral dilemma of cannibalism. It’s talking to a man and staring into the eyes of his corpse barely an hour later. It’s knowing that it’s your wife’s birthday, staring out into the stars, and wondering where she is and if she’s alive anymore.

“I’m in a nice room with my own aircon,” tweets a contented Luke Ellis from Howard Springs, “I’m sitting back watching Netflix on free Wi-Fi. I had barra with garlic butter and broccolini for dinner. I’m in constant contact with loved ones.” “The food is amazing.” But Ellis’s best observation? “If it’s a ‘genocide’ it’s a pretty shit planned one.”

Howard Springs is not a concentration camp. To say so is to do violence to the English language. Its builders were probably closer to the mark when they described it as “a stylish, innovative and sustainable accommodation village” that can house 850 people. In the Northern Territory, known for its rough edges, the accommodation at Howard Springs is the equivalent of a five-star resort for some people. For people from outside the Territory, it would inevitably fall short. But as a sprawling complex that affords exercise and a large pool during the day, even people from outside the Territory have preferred the facility to other quarantine arrangements in Australia. “We thoroughly enjoyed it,” reported one person out of Howard Springs to Australian news media. Another said, “I couldn’t ask for anything better than this. There’s so much freedom here compared to the Sydney hotel.”

There’s no point pretending that anybody in the Howard Springs accommodation village is going to walk away with the memory of a lifetime. Quarantine is a boring and frustrating experience. More than one person has absconded quarantine from Howard Springs over its tiny fence. I merely mean to point out the drivel here—and it is drivel—to equivalate a two-week stay in air-conditioning, with freshly cooked meals, pool, high speed internet, and Netflix, with the worst horrors of the 20th century.

Now, I do want to talk about a video that some people might consider evidence of misdoings. No, it’s not footage of the army doing anything. Despite nearly ubiquitous smartphone ownership and wide use of YouTube for uploading videos of these communities, by some awful stroke of bad luck, nothing has been captured of this. Rather, the evidence cited online seems to be a video of eight indigenous people standing in front of an Aboriginal flag reiterating many of the claims earlier described about forced vaccinations and the military. The fact that there are Aboriginal people in existence who share these views is decisive evidence for some. One tweet of the video on Twitter with thousands of retweets describes the speakers as “Aboriginal Representatives,” insinuating them to be chosen ambassadors speaking on behalf of the plight of indigenous people in the Katherine area. I can count about a dozen large Twitter accounts that have re-tweeted this description, including the American news anchor Greg Kelly. But the people in this video are not community leaders. They’re not even here in Katherine. They’re no more representative of Aboriginals than if any group of white people were selected at random to speak on behalf of the rest of white people.

Some of the speakers are well known in Darwin as local crackpot conspiracy theorists on the fringes. Every jurisdiction has them. The main speaker in the video, David Cole, believes that COVID vaccines are bio-weapons. When he’s not offering ideology-driven pseudo-legal advice to other indigenous people that lose them their court cases, he’s spending time trying to convince others that vaccines are engineered to kill them. He has made specific claims about vaccines that an NT Health spokesperson has specifically refuted and was recently dressed down in public by one of the most respected indigenous doctors in Northern Territory, Dr. Aleeta Fejo, for spreading misinformation. Community leaders here in the Territory are sick to death of him, as are those who he’s tried to counsel on his sovereign citizenship ideology. As the indigenous leaders of Binjari and Rockhole communities said this week, “We don’t appreciate outside people making comments that are untrue.”

Another Aboriginal commentator to draw attention across social media is

the Larrakia elder June Mills. Like the others, Mills is hundreds of

kilometers away in Darwin. But in a video posted to YouTube four days

ago, Mills screams about the situation here in Katherine and surrounding

areas, reiterating again that the army is force vaccinating people and

killing them. In a show of genuine concern, Mills begs for people in

Binjari and elsewhere to contact her with the truth. A few days later

Mills offered a retraction.

The fact that a bunch of social and ideological outcasts hundreds of kilometers away can cast themselves as spokespeople of indigenous communities, by merely standing in front of an Aboriginal flag, is exactly why proximity to the Northern Territory can be a big help in sobering people to the truth. Two defining features characterize the profile of most people spreading misinformation online about the Territory. The Chief Minister of the Northern Territory, Michael Gunner, identified both this week. “Ninety-nine-point-nine percent of the BS that is flying around on the internet about the Territory is coming from flogs outside the Territory,” the chief minister observed. His second and equally astute observation is that they are “tinfoil hat wearing tossers.” To expand on this eloquent point, they are usually sufferers of a particular brand of victimhood politics that puts them at risk of persecutorial ideation, whether of the traditional left variety concerned for indigenous people, or the anti-vaccine, anti-lockdown right concerned with a slippery slope towards tyranny. Misinformation results from the toxic combination of these two defining features, a lack of proximity to the Territory, and viewing the world through the lens of oppression.

Consider Amnesty International, an organization dedicated to scanning the world for oppression, a noble cause, but one that predisposes them to the risk of identifying false positives. In a twist of events this week, we saw a bizarre show of friction between two different organization branches. The variance within Amnesty began when Amnesty International UK re-issued a statement made by Amnesty International Australia about the situation in the Territory, but altered the Australian message to insinuate that the Australian Defence Forces were causing trauma to indigenous people. In perturbed response, the director of Amnesty International Australia, Sam Klintworth, released a joint statement with John Paterson of the Aboriginal Medical Services Alliance Northern Territory. “I am extremely disappointed that Amnesty International UK has chosen to believe and spread false information about what is happening in the Katherine area of the Northern Territory of Australia with respect to involvement by the Defence Forces and others,” Paterson said in the joint statement. “We’re very disappointed that Amnesty UK re-issued a release that we at Amnesty Australia were very careful to ensure was doing precisely the opposite of feeding the spread of harmful information,” Amnesty Australia’s Klintworth said in the statement. “We are deeply sorry for the distress this has caused.” Amnesty International Australia, observing and working closely with people on the ground here, obviously has a very different picture of what is happening than a branch of Amnesty on the other side of the planet.

The fact that America has over 2,300 coronavirus deaths per million people against Australia’s 77 coronavirus deaths per million permits us to use all kinds of adjectives to describe the success of Australia relative to the United States in saving lives in this pandemic: Astonishing, overwhelming, irreproachable.

It would, you would think, precipitate caution on behalf of any American to make commentary. But if publicly available data offer no antidote to misguided commentary, the fight against misinformation about particular remote communities is all the more difficult to dispel to people on the other side of an ocean. Thankfully, as the late Christopher Hitchens reminded us, “What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.”