Art and Culture

Does Christine Brown Deserve to Burn in Hell?

In the pitiless moral universe of writer-director Sam Raimi’s 2009 horror film ‘Drag Me to Hell,’ guilt isn’t easily absolved and debts must always be paid in the end.

NOTE: To mark Halloween, Quillette editor Jamie Palmer writes about one of his favourite modern horror films. Please be aware that this essay discusses the plot in its entirety and contains spoilers from the start.

A clever modern parable of guilt and retribution, Sam Raimi’s 2009 horror carnival Drag Me to Hell confronts its heroine with a moral dilemma and then charts her increasingly frantic attempts to escape the consequences of her choice. Country girl Christine Brown leaves the unhappy circumstances of her upbringing for what she hopes will be a better life in California. There she meets her devoted boyfriend, a handsome young college professor named Clay, and secures a steady job as a loan officer in a Pasadena bank, where she is competing with an obsequious colleague for promotion. When Christine refuses an ancient gypsy woman an extension on her mortgage repayment, the wretched crone confronts her in the parking garage and curses a button she seizes from Christine’s coat. Pursued by phantoms and vivid hallucinations, Christine discovers she has three days to remove the curse before a demon arrives to carry her into hell.

Drag Me to Hell was Raimi’s 13th feature and his first horror film since 1992. It was also the first film since the postmodern Western The Quick and the Dead in 1995 that really felt like a Sam Raimi picture. Raimi had first attracted attention in 1981 with his low-budget horror classic The Evil Dead, which announced the 22-year-old director as an unusually precocious and imaginative talent. The movies he made subsequently during the ‘80s and early ‘90s, including his two Evil Dead sequels, are readily identifiable by his idiosyncratic style—the hectic pacing, a fondness for wide lenses and extravagant camera pyrotechnics, abrupt spasms of ultra-violence and gallows humour, and an exhilarating sense that the director didn’t have everything entirely under control. They’re somewhat uneven but they fizz with energy and ideas and they’re great fun.

After The Quick and the Dead, however, Raimi adopted a more restrained and classical approach that dispensed with his signature style entirely. This change of pace resulted in his most rewarding film to date, the riveting psychodrama A Simple Plan, which suggested that he might be about to embark on a more subdued but no less rewarding creative phase. But his next two features—a sentimental baseball movie starring Kevin Costner (who else?) and a supernatural murder mystery starring Cate Blanchett—were disappointing. Switching gears again, he followed these with his three mega-budget Spider-Man spectaculars, which brought him box office success and returned him to an idiom in which he was clearly more comfortable. The vibrancy was back, and all three films included dazzling sequences reminiscent of their director’s best early work. Still, they were super-expensive studio projects, so it wasn’t quite the same. Given the amount of money involved, everything was now completely under control, and Raimi moderated some of his more abrasive proclivities—the black comedy wasn’t as pronounced, the violence wasn’t as graphic or grotesque, and the moral universe in which the stories unfolded was rather more forgiving and just than that against which Raimi’s early protagonists were forced to struggle.

The third Spider-Man film also marked Raimi’s return to screenwriting with his elder brother Ivan after a lengthy stretch directing other people’s material. At some point during its production, they evidently decided that it was time for another change, and returned to a short story they had written together in 1992 during production of the third Evil Dead film, Army of Darkness. This project would provide Raimi with an opportunity to direct the kind of picture he hadn’t made since the mid-‘90s. It would be a return to a more modest budget, a return to the horror genre, and a return to a world in which Raimi’s characters become the terrified playthings of a sadistic ringmaster. Stories of this kind often unfold as morality plays, in which the writer and director subject an unsympathetic man (it’s usually a man) to an ordeal to teach him a lesson. By the end, he is broken and humbled, attains self-awareness, and emerges the other side a better person—the cynical TV weatherman in Groundhog Day; the cold-hearted banker in The Game, the philandering publicist in Phone Booth.

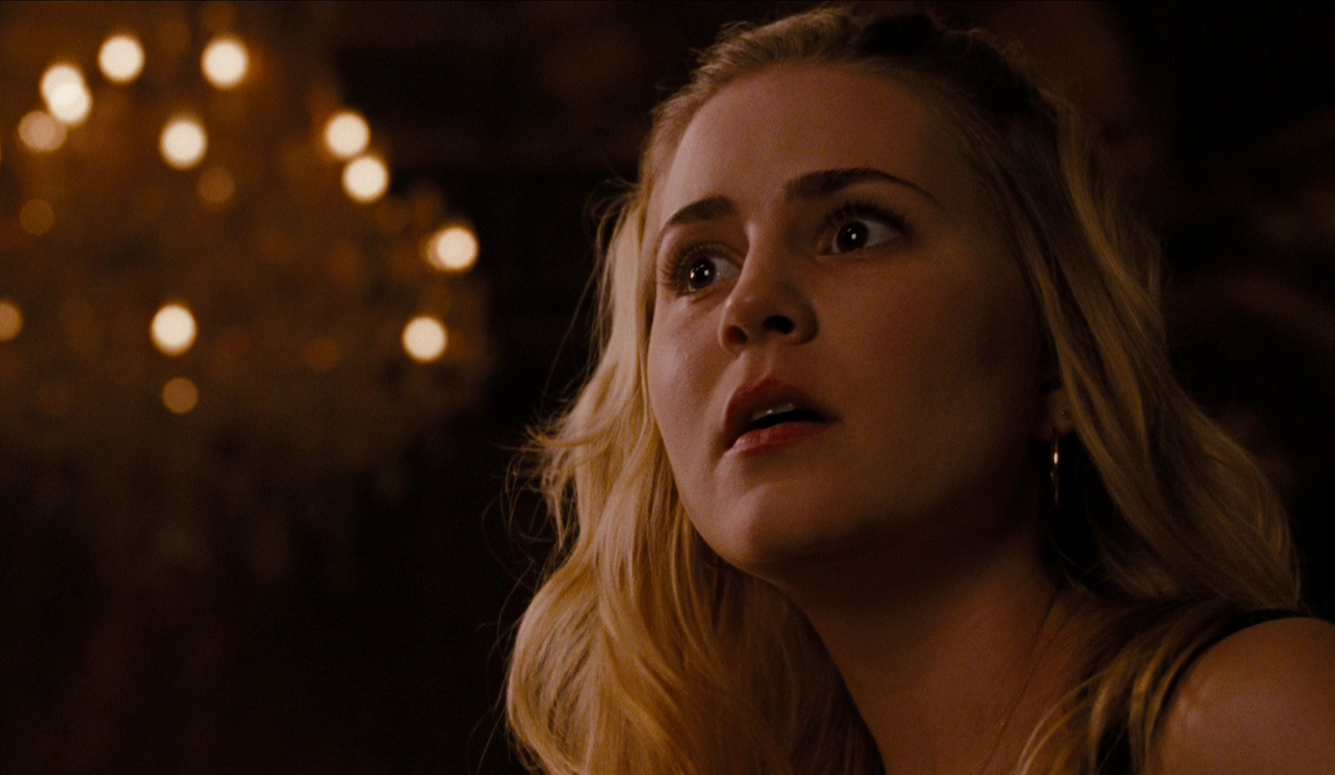

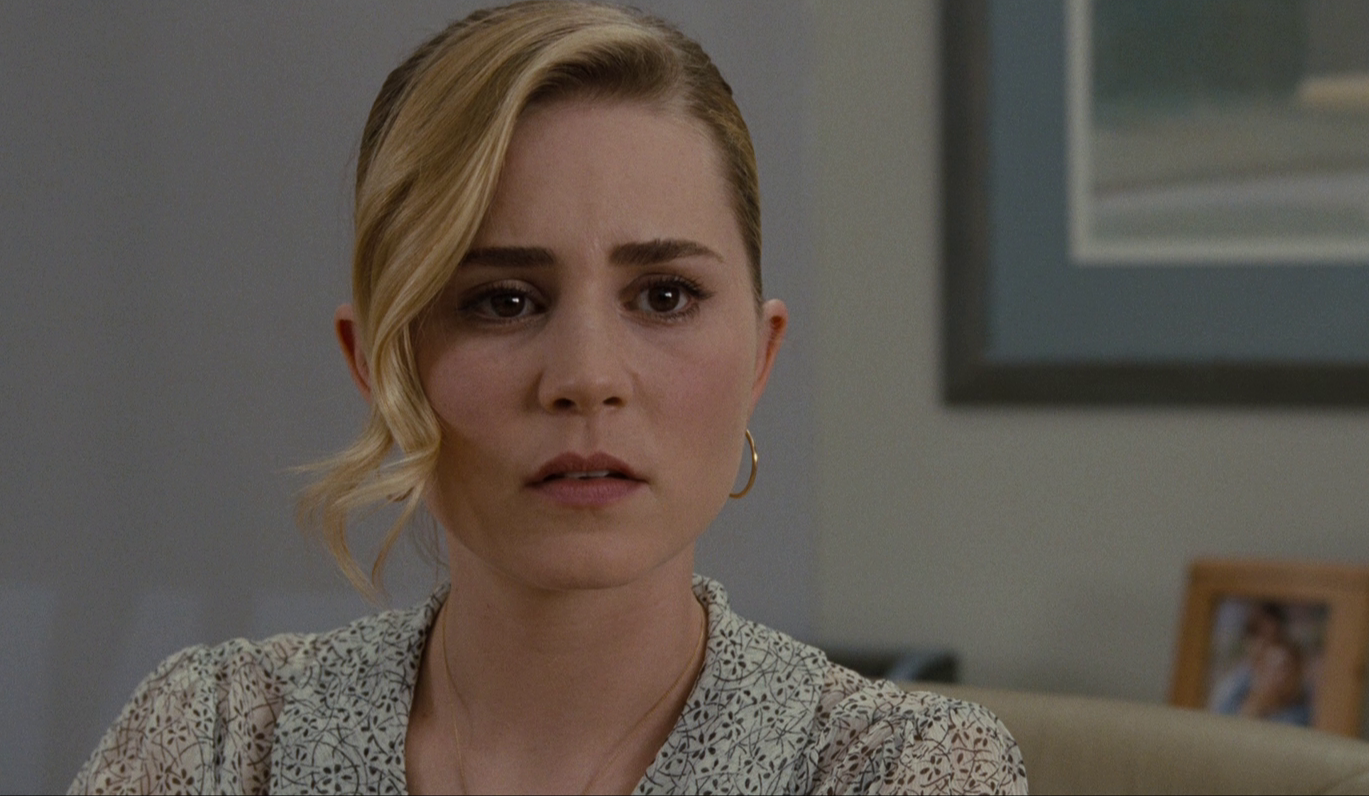

But Christine Brown is not at all like these men. She’s a callow farm girl in a strange city, unsure of herself, patronised at work, and fearful of losing the lover she adores. Nor is she unsympathetic. On the contrary, Raimi is at pains to stress that she is sensitive, compassionate, and charming—exactly the kind of person who does not generally need to be taught a life lesson. Elliot Page was initially selected for the role (before his transition) but dropped out at the last minute to star in Drew Barrymore’s film Whip It. This turned out to be a stroke of luck, because Page’s replacement Alison Lohman is perfect in the role. Her expressive, guileless face radiates warmth, and her delicate features register every flicker of emotion and each successive blow to her hopes. Raimi has cited Lohman’s likeability as the reason he cast her, and this characteristic is critical to his schema for a couple of reasons.

Most obviously, it aggravates our sense of injustice as Raimi gleefully heaps misfortune and humiliation over her. As the vindictive conductor of the havoc consuming Christine’s life, Raimi has a lot of fun at his protagonist’s expense, most of which is played as Grand Guignol comedy. The elderly and frail gypsy woman, Sylvia Ganush, is a pitiable figure in many respects, but she’s also physically repulsive. Her hands are gnarled, her nails and dentures are rotten, she has a milky eye, and she hacks thick phlegm into a filthy handkerchief which she then drapes across Christine’s desk. Raimi invites us to share in Christine’s reflexive disgust, and then ruthlessly punishes her for it at every opportunity.

During the struggle for the button in the parking garage, Mrs. Ganush’s dentures are knocked out, and as she falls forward, her drooling gums fasten around Christine’s chin. During a vivid nightmare, Mrs. Ganush appears in Christine’s bedroom and vomits soil and maggots into her face. When Christine calls on Mrs. Ganush to beg her to lift the curse, she finds herself at the old woman’s wake and accidentally knocks her body out of the coffin. The corpse falls on top of her and expels a quart of embalming fluid into her shrieking mouth. When she drops an anvil on the head of an apparition in her garage, its eyes and brains are splattered across her face. And the more of these comical indignities Christine suffers, the more sympathetic she becomes. We will her on, hoping that her resilience in the face of such monstrous adversity is eventually rewarded.

But Christine’s congeniality also helps to obscure her stubborn refusal to acknowledge her part in what is happening to her. In fact, when identified by Mrs. Ganush’s daughter as the woman who took her grandmother’s house, she explicitly denies it: “Actually, it was the bank who took her house,” Christine replies without much conviction. “I mean, I just work there. In fact, I tried to help your grandma get the house back, but my boss wouldn’t let me.”

That’s not really true. Christine does tell Mrs. Ganush that she will consult her boss, and she does make it clear to her boss that she doesn’t want to throw the old woman out of her home. But while her boss is unsympathetic, he leaves the final decision up to her. And so, caught between her conscience and her professional aspirations, she hardens her heart and sternly informs Mrs. Ganush that “another extension on the loan is out of the question.”

Christine learns of the price she must pay for this decision from Rham Jas, a psychic she visits. He informs her that a malevolent spirit known as the lamia will haunt the owner of the cursed button for three days before dragging her into hell. Will burning the button lift the curse? “I’m afraid not,” Rham replies. “No matter what condition the button is in, you would still be the owner.” He offers her three possible options: the first is an animal sacrifice to the lamia, a suggestion Christine adamantly refuses (“I’m a vegetarian”) until a poltergeist attacks her, at which point she immediately butchers her house cat and slings its corpse into a shallow grave at the bottom of her garden. That doesn’t work.

Following a catastrophic dinner with Clay’s appalled parents on day two, during which Christine coughs up a live fly and shrieks at hallucinations, Rham suggests a séance. In 1969, a local medium watched a small child who had stolen a gypsy necklace being dragged into hell in front of his terrified parents (a scene dramatized in the film’s pre-title sequence), and vowed to confront the lamia again. She offers to summon the demon and cast it into a goat which they will then slaughter. During the séance Christine again tries to blame her boss (“It wasn’t me! It was my manager, Jim Jacks!”), but the séance goes badly awry—the lamia escapes and the medium suffers a fatal coronary.

As day three draws to a close, Rham tells her that only one possibility remains. He takes the button and places it in a small white envelope. If she makes a gift of it, he tells her, she will no longer be the owner. The only problem is that the person to whom she passes the button will then be dragged to hell instead. Later that evening, Christine gazes around at the customers in a diner as the minutes tick away. She briefly considers passing it to a very elderly man at a table on the other side of the restaurant. Then she decides to pass it to her work rival. But in both cases she takes pity on the intended recipient and relents.

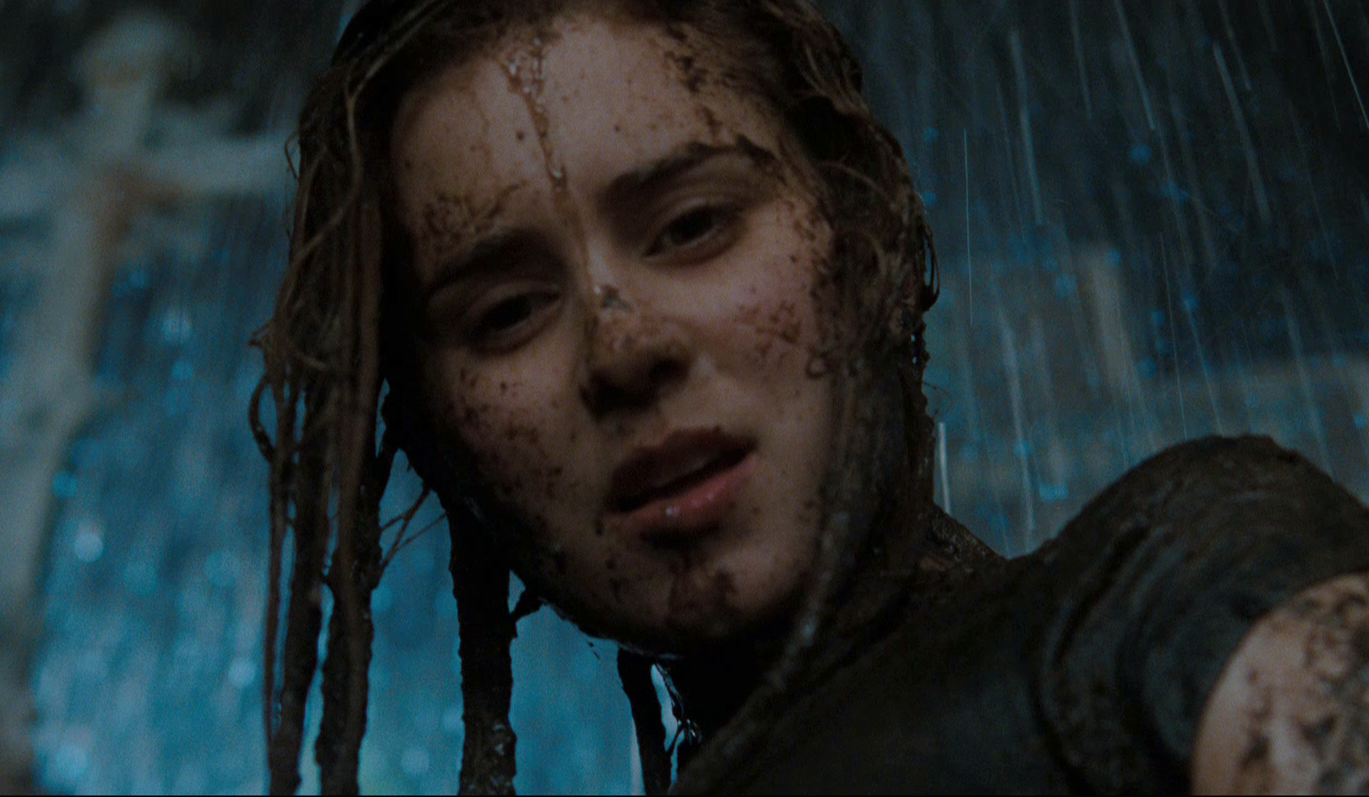

Then she notices Mrs. Ganush’s obituary in the local paper on the countertop. What if she returned the button to the dead gypsy? She calls on Rham Jas who confirms that, yes, the curse can be transferred in this way, provided a formal gift is made of the cursed object. A viable escape hatch! Beneath gathering storm-clouds, Christine drives to the cemetery with a shovel, and as the rain tips down and the thunder crashes, she digs down to the casket and prises open the lid. Forcing open the dead woman’s jaws with her shovel blade, she takes the envelope from her pocket and holds it up to the sky: “I, Christine Brown,” she cries into the howling wind, “do hereby make a formal gift of this button to YOU, Sylvia Ganush!” And with that, she drives the envelope between the cadaver’s rotting gums.

As she scrambles out of the grave, soaked in rainwater and caked in mud, the clouds part and her ordeal finally seems to be over. The next morning, warm sunlight bathes her flat. And as she prepares to leave for the station to meet Clay for a romantic weekend trip, Christine receives a message from her boss informing her that her work rival has been fired, and that the assistant manager position is hers. When she arrives at the station, she spots a coat she likes in a shop window and persuades the owner to open early so she can purchase it for the weekend away.

On the station platform, meanwhile, Clay anxiously awaits her arrival with an engagement ring. She approaches him with a bright smile in her new coat, and they embrace. Then she says this:

There’s something I want to say while I have it straight in my head. You never stopped believing in me. Thank you for that. And there’s something else. Something I couldn’t admit to you before. I could have given Mrs. Ganush another extension on her loan but I didn’t. It was my decision, and it was wrong of me.

Clay rewards her by cupping her face in his palms and kissing her tenderly, as she knows he will. “You have such a good heart,” he tells her. She smiles bashfully and drops her gaze. “You like my new coat?” she asks. “I do, I really do,” he replies. “But what happened to the old one?” “I threw it out,” she says. “And I never want to see it again…”

At this point, we might expect the camera to crane up, the strings to swell, and the credits to roll. Courage and resilience have brought deliverance, good has defeated evil, and the curse has been returned to its malevolent owner. Not only has our heroine won her promotion, but her rival has been sacked, she has rescued her relationship, and she has cleared her conscience with a redemptive confession. All that remains is for the lovely young couple to enjoy the fruits of her triumph in matrimonial bliss.

But according to the medieval sense of justice governing this pitiless moral universe, guilt isn’t absolved and debts are always paid in the end. So, Raimi saves his nastiest surprise for last, with a twist foreshadowed by an apparently innocuous exchange in one of the film’s earliest scenes. The same day Mrs. Ganush visited the bank, Christine dropped in to see Clay at his office during her lunch break and mentioned that she’d brought him a 1929 standing liberty quarter for his coin collection. Cluttered among other expositionary chatter, this detail is easy to miss—the only clue to its significance is that when Clay slips the coin into a small white envelope, the action is covered in a brief close-up. The coin is then only mentioned again in passing during small talk about Clay’s hobbies during the disastrous dinner at his parents’ house.

The trap is finally sprung with only moments of the film remaining. It’s a shame you threw away your old coat, Clay tells her removing a small white envelope from his pocket, “because I think you have my standing liberty quarter.” When Clay picked Christine up in his car after the séance, the envelopes had got mixed up. As he produces her coat button from inside the envelope, Christine reels backwards and falls from the platform into the path of a speeding locomotive. And as the train bears down on her, the earth opens up between the rails and she is dragged screaming and panic-stricken into the inferno below.

Like the protagonist of Stephen King’s novel, Thinner, who also makes the mistake of crossing a vengeful gypsy, Christine finally discovers that there’s no earthbound escape from cosmic condemnation. Raimi isn’t interested in the therapeutic benefits of suffering or the redemptive value of struggle; he’s a dramatic ironist interested in our capacity for moral complacency and self-deception. Most of us think of ourselves as well-meaning and decent people who try to do the right thing, but acts of betrayal and callousness are easily rationalised as expediency or convenience require. “Maybe I could have gotten her another extension on her loan,” Christine tells Clay anxiously the evening after her encounter with Mrs. Ganush, and immediately receives the reassurance she’s after. “You said the bank granted this woman two extensions already, right?” he replies. “I’m sorry, if you don’t pay your mortgage, you lose your house. What does this woman expect? It’s not your fault and you can’t beat yourself up over it.”

Except that was not the reason for Christine’s decision at all. Had Mrs. Ganush’s request not collided with her self-interest, she would have given the gypsy a break, as her first and more generous instinct inclined her to do. She knew her decision would cause the old woman would lose her home, and she knew that was wrong, but she took it anyway because Mrs. Ganush was standing between her and the promotion she wanted. And in her attempts to evade the consequences of that decision, she blamed her boss, slaughtered her cat, indirectly caused the death of an elderly medium, and desecrated Mrs. Ganush’s grave in an attempt to send the old woman to hell in her place. And for all this she is to be rewarded with the full suite of her heart’s desires?

“Who does deserve this?” Christine wonders as she agonises over who she can persuade to accept her button. And the answer is Christine Brown, which is why she is unable to get rid of it. Her eternal punishment may be excessive, but it belongs only to her. And so, likeable or not, down into hell she must go.