media

The Vox Formula: Telling Privileged People What They Already Believe

The confusion of having an elite, educated status with having information, facts, and knowledge should by now be familiar—it is a move that journalists have made repeatedly to capture a high-end market and then clothe that market-driven decision as a journalistic value.

In 2014, Ezra Klein, a 29-year-old journalist known for his Washington Post articles breaking down the thorny ins and outs of complex government policy, left the Washington Post for Vox, a website whose “mission is simple: Explain the news.” Vox would soon become famous for a style of journalism known as the “explainer”—an article that takes advantage of the Internet’s limitless space to give readers the expansive backstory behind whatever news topic is trending that day.

If you’ve never heard of Vox, that’s probably because it’s not for you; from its inception, the site had a very specific audience in mind: young, affluent, and highly educated. Klein and his coeditors were writing for urban millennials under 35 heading highly educated households that made over $100,000 a year, the New York Times reported.

Vox’s trademark style would be a cheeky, barely concealed smugness that flatters its readers into believing that by reading the website—which, not coincidentally, would sustain all of the liberal opinions that young, affluent, educated people already hold—they can rest assured that they are among the ranks of the correct, the informed, rather than one of the stupids.

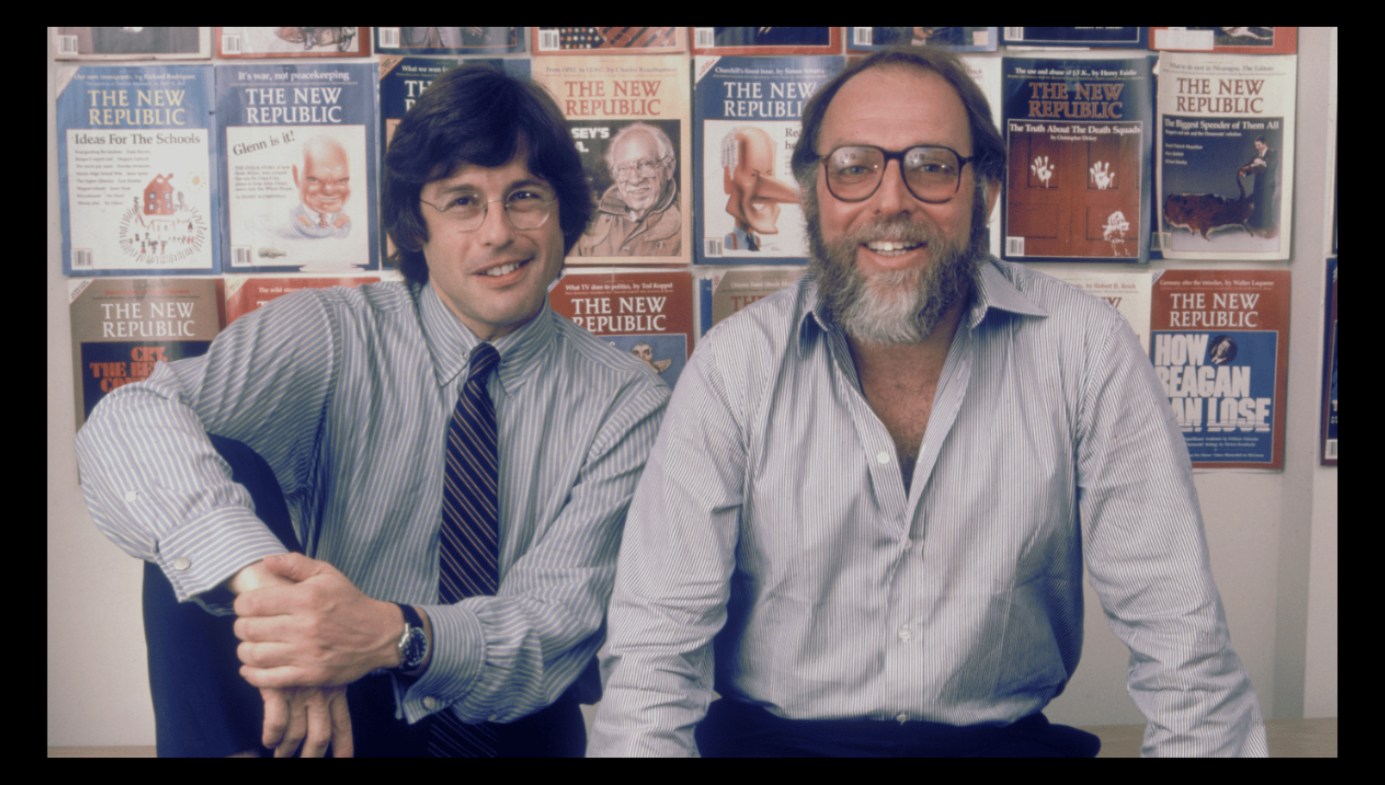

In combining that smugness with a youthful, Whiggish optimism that equates information with progress, Klein figured out how to commodify being in the know in the social media age. After all, the point is not to know things so much as it is to broadcast that you know them. And the folks at Vox realized there was a goldmine to be had if they could turn sharing a Vox article on social media into the method whereby someone signaled their identity, the way a certain kind of person used to walk around with a New Yorker magazine peeking out of her handbag. In other words, Vox capitalized on one of the mainstays of the journalism status revolution: the anxiety members of broader elite classes have about whether they are elite enough.

The confusion of having an elite, educated status with having information, facts, and knowledge should by now be familiar—it is a move that journalists have made repeatedly to capture a high-end market and then clothe that market-driven decision as a journalistic value. But Vox took things one step further, leaning deeply into the view that reality itself has a liberal bias—one that incidentally appeals to and protects the status of progressive elites.

You can see this slippage everywhere in the site’s branding. Vox calls its articles explainers, as though these explanations are happening in a political vacuum instead of confirming the biases of affluent liberals. The Vox gambit was to bet that there were millions of readers like Klein, part of an educated meritocratic elite, who liked intricate policy discussions so long as everything they encountered confirmed their previously held beliefs.

But the Vox explainer was designed to appeal to an even smaller set than simply highly educated people; it was designed for people nostalgic for school.

The site was visually crafted to evoke a sentimental response to the gear of the nerd: Its main focus was initially going to be “Vox Cards”—explainers that were “inspired by the highlighters and index cards that some of us used in school to remember important information,” as Klein and the other founders described them in a post introducing the concept of the site. The Vox reader would be thrilled to see the hallmarks of their schooldays so deployed, thrilled to eat the “vegetables or spinach” of the news and be inside “the club,” as Klein put it, taken there by the bright young editors of Vox who love being “in the weeds.”

The idea of the cards was eventually abandoned for the lengthy explainers that are now Vox’s bread and butter, tagged to the news of the day and formatted to pick up Google traffic with techniques like repeating words, listing questions in boldface that people have plugged into search engines, and other tricks of the trade. It was a nimble pivot to sit better athwart the feedback loop between the tools of digital media and the audience they sought to capture.

And capture Vox did. In the past seven years, the site has amassed tens of millions of unique visitors every month. Flush on success, Vox Media, Vox’s parent company, has been swallowing up other media companies and publications—most recently, New York magazine, another publication designed to profit off of the class anxieties of the meritocratic elite. In 2015, after raising more than $300 million in funding, including $200 million from NBCUniversal, the company was valued at $1 billion. And despite the pandemic woes that afflicted many in the news industry, Vox Media Studios is planning to bring in $100 million in revenue in 2021.

Vox has become the reference point for other media companies trying—or failing—to make it in the digital age. It is the model that everyone else is aspiring to. Recently, the New York Times itself poached Klein.

So what’s the secret sauce behind Vox? Klein divulges some of it in his book Why We’re Polarized, where he discusses how tracking readers’ behavior in real time with digital analytics has turned media companies into purveyors of identity rather than information. As we have seen, the current business model of digital media is less about selling ads, whose online prices could never compete with those of print, than it is about selling reader engagement, which means that the incentive is to produce work that will get shared online, widening its impact in the hopes that it will go viral.

“We don’t just want people to read our work,” writes Klein. “We want people to spread our work—to be so moved by what we wrote or said that they log on to Facebook and share it with their friends or head over to Reddit and try to tell the world.” The thing is, people don’t share articles that don’t produce some kind of big emotion within them, he explains. “They share loud voices. They share work that moves them, that helps them express to their friends who they are and how they feel. Social platforms are about curating and expressing a public-facing identity,” Klein goes on. “They’re about saying I’m a person who cares about this, likes that, and loathes this other thing. They are about signaling the groups you belong to and, just as important, the groups you don’t belong to.”

To exemplify his point, Klein lists headlines from BuzzFeed like 53 Things Only ’80s Girls Can Understand and 19 Comics Only Night Owls Will Understand, which Klein sees as evidence of “identity media.” “When you share 38 Things Only Someone Who Was a Scout Would Know, you’re saying you were a Scout and you were a serious enough Scout to understand the signifiers and experiences that only Scouts had,” writes Klein. “To post that article on Facebook is to make a statement about who you are, who your group is, and, just as important, who is excluded.”

Vox, of course, is playing the same game, though Klein’s articles don’t appeal to the identities of night owls or ’80s girls; unstated in Vox’s headlines is a quiet appeal to identity, one that does not need to be articulated but rather is conveyed to you through the topics, tone, and even appearance of the pages on the site, which all coalesce into a whisper in the reader’s ear: “8,000 words about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict that only a college-educated millennial making more than $100,000 a year can truly understand.” And perhaps even quieter, “Everyone you disagree with is not in this club because they aren’t smart enough.”

Thus. headlines like Toward a Better Theory of Identity Politics and The Radical Idea That Could Shatter the Link between Emissions and Global Warming and How to Solve Climate Change and Make Life More Awesome. It’s smug optimism at its best, animating and reinforcing the select nature of elite group belonging—a magic trick that clothes readers’ affluence and privilege in a flattering façade of intelligence, information, and data, when, in reality, the site is just selling readers their own liberal values back to them at a discount.

The group that Vox signals that its readers belong to is the group of people going to dinner parties in big coastal cities where they are guaranteed to meet no one who disagrees with them. Vox’s explainers are confirmation-bias catnip, fodder for happy hour at a Google campus or in the Flatiron District of New York City, for people who leave that happy hour to go home and watch the Daily Show, the mothership of smug privilege masquerading as outrage at injustice. The smugness isn’t a bug of Vox; it’s one of its main features—a signal that its content belongs on the carefully curated social media page of an urban millennial.

People have criticized Vox for its left-wing bias, which, coupled with the heavy emphasis on data and “explaining,” gives the impression that “liberal political values are implicitly assumed to be factually correct,” one critic suggests. Others point out that for a website focused on information, Vox has published quite a few major errors. But what Vox has done is actually much more interesting—and much more common: It has taken a question of class—a certain level of affluence, educational achievement, and discursive style—and sold it as truth, information, data. It sells being “informed” as belonging to a certain class and having a certain kind of identity, which was created by excluding anyone without a college degree, or anyone whom the sight of a highlighter might cause to sweat.

In this, Vox is not unusual, though it has been unusually successful at what BuzzFeed CEO Jonah Peretti called the “Bored at Work Network”—“all those alienated office workers worldwide who had time to kill during the workday while staring at their desktop computers and trying to look busy.”

Think about it: A day laborer may have time to enjoy one photo of a cat who’s having a worse day than he is, but only a college-educated millennial bored at their office job has time for a listicle of 29 cats having a worse day than he is. What Peretti inadvertently exposed was the hidden class story of the national digital media industry.

And if BuzzFeed and Vox were once the digital frontier, no less august an institution than the New York Times has made a habit of poaching talent from the two outlets and copying their digital strategy in recent years. Indeed, the Times’s pivot to digital was one of the most surprising success stories in the industry—even if it wouldn’t have been possible without the assistance of Donald Trump.

Excerpted, with permission, from Bad News: How Woke Media Is Undermining Democracy, by Batya Ungar-Sargon. © 2021 by Batya Ungar-Sargon. Published by Encounter Books.