Tech

Lessons for Big Tech from Ralph Nader’s ‘Sack of Detroit’

Tech giants were slow to confront the regrettable purposes to which their platforms and systems were being put, preferring to single-mindedly pursue growth and profits.

Until recently, Silicon Valley enjoyed a relatively high degree of freedom from US government regulation. That was a deliberate policy choice. Responding to public enthusiasm for the possibilities of global interconnectedness and an endless stream of easily accessible information, Congress decreed early that online platforms would have no liability for third-party content flowing through their pipes. As a tool of progress, the Internet would be free.

Tech companies harnessed the massive energy exerted by billions of people eager to gain a presence online, to share, to learn, to be entertained, to work, to shop. The web remade the United States physically, economically, and socially. Web culture became American culture and, increasingly, global culture.

It was only when the wonders of the Internet grew familiar, and tech companies became huge and powerful, that the adverse consequences of connecting everyone without appropriate oversight became glaringly apparent. The Internet was used for pornography, sex trafficking, terrorist recruiting, an infinite variety of scams, the evasion of laws and regulations, the invasion of privacy, harassment and defamation, foreign propaganda, and fake news.

Tech giants were slow to confront the regrettable purposes to which their platforms and systems were being put, preferring to single-mindedly pursue growth and profits. This was predictable. That capitalists will “esteem [their] immediate interests … to be the common Measure of Good and Evil” was a truism remarked by Restoration-era English economist Dudley North a century before the American Revolution.

The government response, too, has been predictable. Never mind that massive subsidies from the defense establishment have been critical to tech’s progress. Never mind that Congress’s hands-off policy was instrumental in helping Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, and other online giants scale up massively. Politicians are now tripping over one another in a race to investigate, indict, regulate, and dismember tech companies, as if they were solely responsible for the Internet’s ills.

The Justice Department, the Federal Trade Commission, and other agencies at the federal and state levels are pursing big tech for anti-competitive activity, abuse of dominance, promoting hate speech, ruining conventional media, labor abuses, invading the privacy of users, and generally poisoning the public sphere. President Joe Biden has “stacked his administration with trustbusters,” as the New York Times puts it. Other nations, including China, Australia, and members of the European Union, are also on the attack, and sometimes leading it. These governments, reports the Times, are moving “to limit the power of tech companies with an urgency and breadth that no single industry had experienced before.”

Where does it end? Maybe these investigators and regulators will be reasonable, and even prudent. Certainly, it ought to be possible to balance the need to curb tech’s excesses with concern for the finances, reputations, and future prospects of the companies targeted, the welfare of their investors and employees, and the growth and competitiveness of the American economy. And it would be advisable to do so as well, given that what’s happened to the Internet does not solely implicate Silicon Valley, but rather is part of a general social problem for which companies, governments, and individual users all bear some responsibility.

But don’t count on authorities taking the correct course of action. After all, we’ve been here before.

The last great tsunami of corporate regulation struck America a half-century ago. In 1965, regulated industries in the United States represented seven percent of America’s GNP; by 1978, it was 30 percent. Twenty-five substantive consumer and environmental regulatory bills were passed in that time, and hundreds more were considered. The victimized consumer was all the rage. Activists and politicians faced American capitalism in an adversarial pose, armed with shocking facts and moral indignation. Said actor Betty Furness (of Swing Time fame), who’d become Lyndon Johnson’s special assistant for consumer affairs:

You gave us nylon but didn’t tell us it melts. You gave us insect spray, but you didn’t tell us it would kill the cat. You gave us plastic bags, but didn’t warn us that it could, and has, killed babies. You gave us detergents, but didn’t tell us they were polluting our rivers and streams. And you gave us the pill, but didn’t tell us we were guinea pigs.

All of this activity, concluded Lizabeth Cohen, the leading historian of American consumer activism, can be traced to Ralph Nader’s two-year battle with General Motors in the mid-'60s over the issue of auto safety. Nader’s success was “just the spark needed” to produce “a major conflagration” for more regulation and government intervention in the commercial economy.

There is a cloak of mythology around Nader, supposedly a lone author-activist who took on the giants of Detroit, demonstrated that their cars were death traps, and convinced Washington to regulate the automotive sector. Nader is credited with saving hundreds of thousands of lives with his auto-safety campaign. And there is some truth to the legend: He did embarrass GM and he did encourage the federal government to regulate Detroit. But that’s as far as it goes.

Nader was a product of his times, educated at Princeton and Harvard Law School in the 1950s, and influenced by an array of writers and thinkers who chafed at the economic orthodoxies of the Eisenhower years. Ike’s highest priority was economic growth, maintained by constant stoking of the consumer economy. The more people bought and sold, the stronger the economy, and the better America’s chances of out-pacing its global rival, the Soviet Union: that, in a nutshell, was the so-called Cold War Consensus, and not only Republicans but most Democrats embraced it. Every red-blooded American was said to owe it to his countrymen to double what he ate, double what he smoked, and wear three shoes.

Sociologist C. Wright Mills was one opponent of that consensus. He considered it a self-serving invention of America’s “power elites” in government and business, who were enriching themselves by enslaving people to consumerism. Economist John Kenneth Galbraith shared Mills’s skepticism. Why, he asked, should economic growth be Washington’s highest priority when people were already rich enough? Americans enjoyed a material standard of living unexampled in history. If they actually needed more consumer goods, barrages of advertising would not be necessary to convince them.

To Galbraith’s mind, America had solved the age-old problems of economic scarcity and insecurity. It was time to shift its attention from economic growth to better governance, from commercial production of alcohol, comic books, mouthwash, narcotics, pornography, and automobiles, to public goods such as schools, hospitals, urban redevelopment, sanitation, parks, and playgrounds.

Automobiles, then the hottest commodities in the consumer economy, accounting for one in five retail dollars and the largest share of the nation’s advertising, provided critics with their best illustrations of America’s material excesses and social ills. It was not lost on Mills that three positions in Eisenhower’s cabinet were filled by former General Motors men. Galbraith thought it crazy for Washington to worry about private-sector growth when a company such as General Motors, the world’s largest and most admired industrial enterprise, enjoying record profits and funding enormous advertising budgets, was unassailable and in all probability immortal.

Both saw an obsession with automobiles (there were 1.4 in every garage by this time, and consumers were always looking to trade up) as symptomatic of America’s backward priorities. Wrote Galbraith: “The family which takes its mauve and cerise, air-conditioned, power-steered and power-braked automobile out for a tour passes through cities that are badly paved, made hideous by litter, blighted buildings, billboards, and posts for wires that should long since have been put underground ... they may reflect vaguely on the curious unevenness of their blessings.”

Nader had studied Mills at Princeton and was familiar with the works of Galbraith. He and many other young intellectuals and activists shared their rejection of the Cold War Consensus and their anti-corporate worldview. He also shared their intuition that any effort to reduce the influence of consumerism in American life, and forge a new American agenda concerned primarily with public welfare, would benefit from putting a big dent in Detroit. The issue of automobile safety was the instrument Nader would use to make that dent.

The consensus around safety through most of automobile history had been that the car itself was harmless, and that the best way to keep drivers and their passengers from being maimed or killed was to engineer better roads, enforce the laws, and preach driver education—the so-called Three-E approach. Between the early 1920s, when mass-produced cars made their first appearance, and the late 1950s, this method had been sufficient to reduce annual American road fatalities per miles driven by 80 percent.

But because America was growing, and people were driving more, the absolute number of traffic fatalities remained in the range of 34,000 to 39,000 throughout the 1950s, much to the frustration of the medical community, which dealt with a heavy flow of injured, crippled, paralyzed, brain-damaged, and dead victims of automobile crashes through its emergency rooms and operating theaters.

It was American physicians who brought the first real challenge to the Triple-E approach in the mid-1950s. Following the example of pioneering safety researchers, they divided their analysis of every auto crash into two parts: an initial collision, when a vehicle hits a ditch or another vehicle or a moose, and a second collision, when the occupants of the crashing vehicle are thrown into its dashboard, windshield, steering wheel, or some other unforgiving part of its interior, or flung onto the road. From this perspective, it was not the driver’s initial mistake or misfortune that caused injury or death; it was the so-called second collision of human against steel, glass, or pavement. It followed that if vehicle interiors could be designed to better protect people in crashes, road carnage could be reduced.

The appeal of this approach to doctors was obvious. When faced with a body on a stretcher, they usually had no idea what had happened on the road, and did not much care. Rather, they dealt entirely with the consequences of the second collision. They began demanding car manufacturers make the interiors of automobiles safer, or crashworthy. Among their recommendations: pad the dashboards, eliminate finely beveled metal edges, install collapsible steering wheel columns and safety glass, and improve door latches.

With the medical community’s help, second-collision theory caught the attention of a handful of media outlets, the odd congressman, and a Chicago lawyer named Harold Katz. His specialty was torts, the branch of law dealing with personal injuries resulting from wrongful acts that do not necessarily amount to crimes. He read what physicians were saying about second collisions, and wrote a piece of his own on the subject for the Harvard Law Review in 1956, entitled "Liability of Automobile Manufacturers for Unsafe Design of Passenger Cars."

It had occurred to Katz that the legal implications of second-collision theory were immense. If putting humans in cars was like shipping teacups loose in a barrel, as doctors maintained, weren’t automobile manufacturers negligent in failing to better protect occupants from unreasonable risk of injury and death? Surely auto engineers and designers, who had more safety expertise than anyone else, had a duty to build the safest practicable products for their consumers. It seemed clear to Katz that with almost 40,000 Americans dying on the roads every year, automakers were a sitting duck: lawyers should be suing them for the lethal designs of their vehicles.

Katz’s article, implicating the largest, richest companies in America in tens of thousands of annual deaths, was catnip to the personal-injury bar and also to then-law student Ralph Nader. “I got a call from this fellow, I’d never heard of him, but he was quite ecstatic,” said Katz of Nader. “He told me that he was utterly astonished and absolutely delighted by my article. He didn’t have any prior notion of using tort law to reform the auto industry. The idea captivated him.”

Soon after graduating from Harvard, Nader placed an article in the Nation building on Katz’s insights. He not only saw the Triple-E approach to auto safety as wrong-headed, but described it as a plot, led by Detroit, to detract attention from its negligently-designed product. He claimed that automakers had the knowledge and technological means to “make accidents safe,” but were too callous and cheap to do it—far easier to blame drivers for accidents.

Nader outpaced Katz by suggesting that automobiles “are so designed as to be dangerous at any speed,” and suggested a conspiracy of silence around the fact that so many people were dying annually on the roads. Newspapers and broadcasters dared not discuss this “national health emergency” for fear of losing their car advertising. Universities were uninterested in researching the subject due to “widespread amorality among our scholarly elite.” Politicians were timid, and the people needed to be protected from the “indiscretion and vanity” that made them susceptible to Detroit’s sparkling, roaring “death-traps.”

Nader was keen to see tort lawyers attack automakers with second-collision arguments, but he was even more interested in the political implications of Katz’s claims. He believed second-collision theory gave Washington permission to regulate Detroit.

Within a couple of weeks of Nader’s article landing in the Nation, young Daniel Patrick Moynihan, then an academic, placed a similar piece in the April 30th, 1959 edition of a magazine called the Reporter. Moynihan had learned about second-collision theory during his years as an aide to New York governor Averell Harriman. A PhD in history, he was more careful with data than Nader, but just as excited about the prospects for regulating Detroit:

If the industry cannot rise to its responsibilities, the entire matter should be removed from its jurisdiction and be solved by methods employed in any other urgent public health problem … If any automobile magnate wonders what that can mean, he would do well to run over to Chicago to watch government officials in white coats giving their safety ratings to the sides of beef as they roll off packing-house production lines.

Moynihan’s article caused more of a stir than Nader’s, and he signed a contract with Knopf to write a book about auto safety. His self-described goal was to write “descriptions of pain and loss so powerful as to not only advance vehicle safety, but also “impair if not in fact destroy the personal and social symbolism of the American automobile which is as precious to those who manufacture them as to those who buy them.”

More ambitiously, Moynihan, like Galbraith and others before him, believed that cutting General Motors down to size would reduce corporate influence in American life, and shift the focus of government from encouraging consumption of private goods to encouraging the development of public goods. He dreamed of a time when “the central concerns of American society are no longer in the hands of free enterprise, and that free enterprise is no longer in the hands of men who expect to lead society.”

Moynihan worked for John F. Kennedy in 1960, and upon his election to the presidency was rewarded with a job as aide to Labor Secretary Arthur Goldberg. The demands of his career in Washington prevented him from delivering his book to Knopf. But Moynihan didn’t drop the issue of auto safety. He’d begun a friendly correspondence with Nader after their articles had been published. After JFK was assassinated and Lyndon Johnson began planning a more aggressively liberal agenda, Moynihan invited his friend to join him in the Labor department and work on a report about auto safety.

Nader, with not much else happening in his life, jumped at the chance, and in his first nine months at Labor, using the full powers of his boss’s office to collect information and conduct interviews, produced a 234-page first draft of the book Moynihan hadn’t found time to write. Only a few copies of A Report on the Context, Condition, and Recommended Direction of Federal Activity in Highway Safety were printed, and Moynihan’s secretary expressed doubt that even he had read the whole document. It was not widely circulated inside government, and it may be that no one read it. Moynihan would later say he commissioned it primarily so that when advocating for federal regulation of automakers, he could say that he had a 234-page report with 99 pages of notes to back him up.

While Nader was toiling on his report, Moynihan learned that second-collision theory was gaining traction in certain congressional offices. Abraham Ribicoff, a liberal Democratic Senator representing Connecticut, and a former governor of that state, had some experience with consumer issues. He’d received generous press as the main congressional champion of author and environmentalist Rachel Carson in 1963. Having won his office by a slim margin of votes, he was eager to build on that momentum.

Perusing the New York Times one morning in December 1964, Ribicoff came across an article on accident research and second-collision theory in which an anonymous researcher was quoted as saying that Detroit had the wherewithal to build a crashproof car, but couldn’t be bothered.

“It was the first time I’d heard of the car as a factor in accidents,” he said. “I was intrigued by the theory of the second collision. This was a new concept to me.”

Ribicoff telephoned an aide, Jerome Sonosky, and asked him to schedule hearings on the role of the vehicle in automobile crashes.

“This means taking on Detroit,” said Sonosky.

“Can you do it?” asked Ribicoff.

Sonosky could. He and Moynihan quickly found each other, and Sonosky was introduced to Nader.

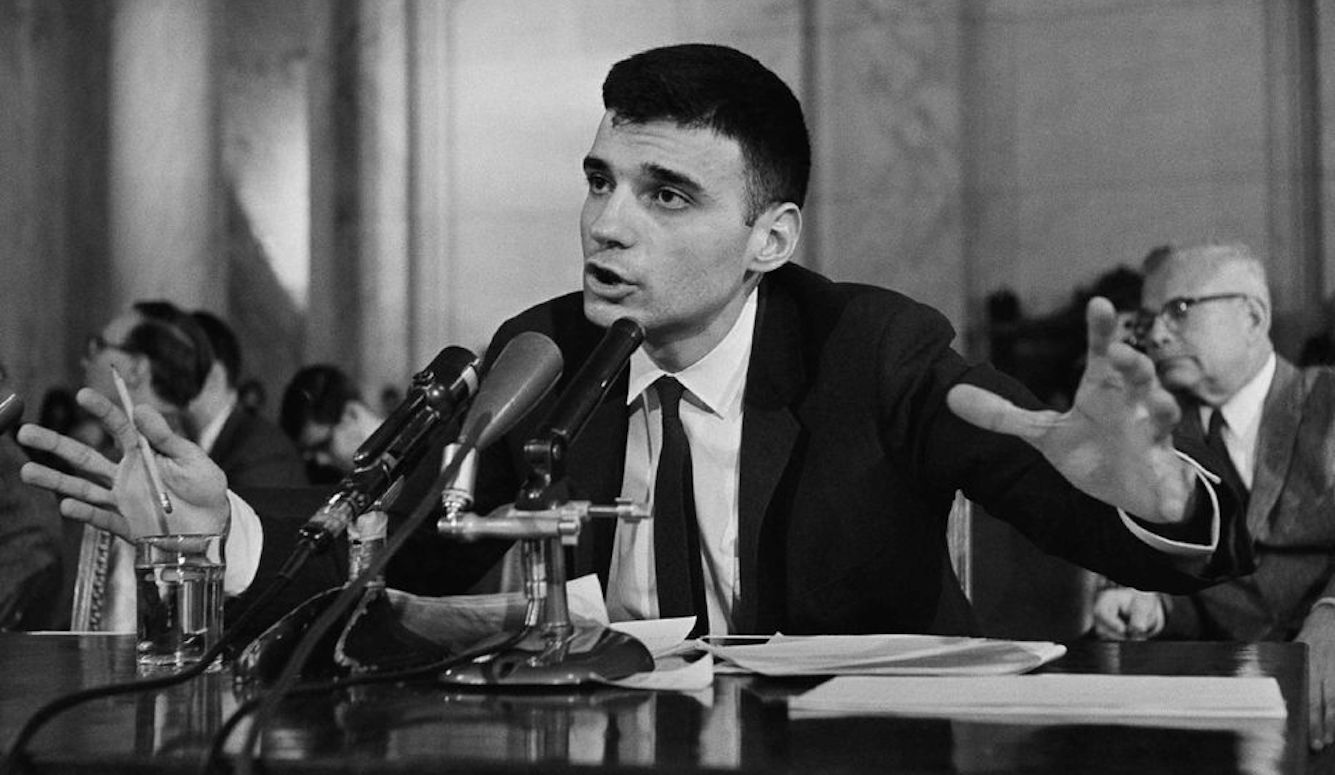

“Nader walked in looking then as he looks now,” said Sonosky later. “Sallow faced. Wearing his long overcoat. Carrying a thousand pieces of paper under his arm. His message was that the auto industry has no right to produce unsafe cars. We talked for three hours about various aspects of the issue, and where we should go with it.”

Said a journalist who knew Nader: “This town is full of guys who wander around with stacks of paper under their arms trying to see senators or bust into magazine offices. Ralph is one who got through the guards.”

Sonosky left his meeting with Nader and immediately called Ribicoff.

“We just struck gold,” he said.

“What do you mean?”

“I just met somebody who knows more about auto safety than anybody I’ve ever come across. I don’t have to run around town gathering up various experts. I just found him.”

Nader, already on the Department of Labor payroll, was also hired as an unpaid advisor to Ribicoff’s subcommittee on the federal role in traffic safety, which would begin hearings early in 1965. In practice, that meant that Moynihan would keep Nader on the Labor payroll for a half year after his report was produced so he could volunteer for Ribicoff.

“Nader was my prime resource, period,” said Sonosky. “I didn’t need anyone else. He had everything.” The pair would meet and talk for hours about the issues, what questions to ask witnesses, and how to handle technical material. “Sometimes I had to shut him up,” said Sonosky. “He was fixated.” Information and tactics they developed circulated among the offices of Ribicoff, Moynihan, and freshman senator Robert F. Kennedy, who was expected to participate in the proceedings.

Several important things happened before Ribicoff’s hearings could get underway. One was that Washington’s General Services Administration (GSA), responsible for procurement of the federal fleet, had been authorized by Congress to require the hundreds of thousands of automobiles it purchased to include padded dashboards, stronger windshields, and other safety equipment. Another was that this application of federal purchasing power, the inspiration of a little-known but effective Alabama congressman named Kenneth Roberts, prompted Detroit, after some grumbling, to adopt for all its cars virtually the whole slate of changes to automobile interiors requested by the American medical community.

This development did not slow Ribicoff in the least. He began his hearings on March 22nd, 1965, and made two important arguments off the top. He claimed there existed in America a “traffic safety establishment,” including police forces, state traffic commissions, and the National Safety Council, among other organizations. Under the influence of Detroit, which provided funding to these organizations and sometimes had representation on their boards, the establishment was misleading the nation by blaming drivers for road carnage when second-collision theory proved that the real problem was negligently designed American automobiles.

Ribicoff’s second argument was that Detroit knew how to make cars crashproof but couldn’t be bothered, and that the public interest required Washington to step in and impose automobile safety standards.

His first three days of hearings didn’t go as planned. The other eight senators who’d agreed to sit on Ribicoff’s panel were largely absent, as was the media. Witnesses from such federal departments as Commerce and Health, Education, and Welfare testified that they saw no need for further federal involvement in auto safety, and praised the automakers, and General Motors in particular, for their leadership on the issue.

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, representing the department of Labor, was a notable exception. He expressed the view that America “had done almost nothing about the problem of traffic safety.” The Triple-E approach, he said, was nonsense. Instead of trying to reform 80 million Americans drivers who were incorrigibly reckless behind the wheel, better to concentrate on a handful of automobile executives in Detroit. In their “considerable obtuseness,” these executives believed safety didn’t sell cars, so they plied an unwitting public with bloated, overpowered, dangerous models rather than crashproof vehicles that would save lives. The federal hammer was required to force a change.

An otherwise dispirited Ribicoff was overjoyed by this testimony: “You make a lot of sense in almost everything you do, Mr. Moynihan. I appreciate your coming here.”

While there had been almost no one in the room to hear any of this testimony, that changed in the second round of Ribicoff’s hearings. He was joined on the rostrum by three Senate colleagues, and the room was abuzz with spectators, photographers, and reporters. The excitement was due to the scheduled appearances of two witnesses from Detroit, Frederic G. Donner, chairman of the board of General Motors, and James M. Roche, president of the company. These barely distinguishable eminences sat side by side at the witness table. When they put their gray heads together to whisper, news photographs made them appear conjoined.

Some at GM thought it a mistake for the executives to dignify Ribicoff’s hearings with their presence. Better to send some engineers and lawyers who would draw no crowds and say nothing intelligible to the general public. But chairman Donner was anxious to put his best foot forward on auto safety. He and Roche prepared and rehearsed for their appearance, and GM made what was intended as a good-faith donation of $1 million to traffic safety research at MIT.

In their opening statements, the GM men professed themselves concerned with the number of traffic deaths in America. They spoke of improvements made in safety glass, door latches, steel roofs, and other equipment; their use of crash sleds and crash dummies and high-speed photography to better understand the dynamics of collisions; and their participation in crash-injury research projects conducted with recognized experts at Cornell University, among other parties. They boasted that they would be meeting most of the GSA’s imposed safety requirements ahead of schedule.

To pre-empt questions about why GM hadn’t rushed to install each new safety technology at the moment it became available, Donner explained that his company operated in “a climate of public acceptance.” People were only willing to pay for so much safety, and would balk if it was forced on them at increased cost. Thus, new safety features tended to be available first as options, and later, once they’d proved themselves, as standard equipment. They pointed out that no one had been willing to pay for turn signals when they were first introduced, but over time consumers were sold on their utility and they became standard equipment on cars even before states, which had primary responsibility for regulating commerce, began to mandate them.

As for building crashproof vehicles, the GM honchos were skeptical. More improvements could be made, they said, but there were limits to technology. A crashproof vehicle was not within the realm of possibility. Driver education, law enforcement, and road engineering were also important.

While the GM men laid down their case, Nader, the Ribicoff panel’s expert-in-chief, sat behind a door in the chamber passing slips of paper to the Senator’s aide inside, supplying information and ideas for lines of attack.

The executives were having a rather easy time of it until New York Senator Robert Kennedy joined the proceedings late. It had been the better part of a decade since Kennedy, as a young Senate aide to Joseph McCarthy, had badgered suspected communists in hearing rooms, but he had not lost a step. He proceeded to steal Ribicoff’s show, describing GM’s gift to MIT as a publicity stunt, and asking chairman Donner how much the company spent annually on safety research.

“Sir, I don’t believe it is a matter of what we have spent,” said Donner.

“Well, I am interested in it. You might not be, but I am, and I am just asking you.”

“We don’t know, Senator, how to add all these things up.”

“You don’t?”

“Because they are scattered all over …”

“General Motors doesn’t know how to add them up?”

Donner tried to explain that some money was spent in research, more through the Automobile Manufacturers Association, and in other directions. He asked if Kennedy wanted to know about pure research, or development and testing, or reliability, or other matters.

“I will ask you some specifics about it,” said Kennedy, confident he had the witnesses on the run. “How much money have you spent to find out how many children … fell out of the back of an automobile because of a faulty latch or lock?”

The executives had no answer.

“How many children have fallen out of General Motors cars?” asked Kennedy. “Last year?”

“I don’t quite know how you would find that out,” said Donner.

Kennedy toyed with the executives, asking more questions he knew they would be unable to answer about their safety spending, and taunting them for their failure. When Roche finally coughed up a hard number, estimating that the company spent $1.25 million in the previous year on external safety research, Kennedy went for blood.

“What was the profit of General Motors last year?”

Roche answered, “I don’t think that has anything to do …”

“I would like to have that answer if I may. I think I am entitled to know that figure ... You spent $1.25 million, as I understand it, on this aspect of safety. I would like to know what your profit is.”

Donner tried to brush Kennedy back, saying that he was in attendance to discuss safety not finances.

“What was the profit of General Motors last year?” repeated the Senator.

“I will have to ask one of my associates,” said Donner.

“Could you, please?”

“$1,700 million,” replied Roche.

“What?” asked Kennedy.

“About $1.5 billion, I think.”

“One billion?” asked Kennedy.

“$1.7 billion,” said Donner.

“About $1.5 billon?”

“Yes.”

“You made $1.7 billion last year?”

“That is correct.”

“And you spent $1 million on this?”

The juxtaposition was fatal. Kennedy berated the executives for making so much and spending so little on safety when there were, by now, more than 40,000 Americans dying on the road every year. Donner and Roche tried to explain that the $1.25 million figure was for external safety spending, not the sum total of the company’s safety expenditures, but the fact that they could not specify the sum total negated their point and brought more abuse from Kennedy: “I cannot believe General Motors does not have this information.”

Ribicoff and Kennedy brought the proceedings to a close by congratulating one another on their commitment to improving traffic safety when so many of the individuals and organizations nominally responsible for safety were sitting on their hands.

Even GM insiders acknowledged that the executives were clobbered at their appearance. The Wall Street Journal reported on July 20th, 1965 that they were “astonishingly ill-prepared,” and declared their performance “dismal.” The newspaper quoted a congressman as saying, “I really wouldn’t have believed they could be so bad.” GM later tallied all of its spending on safety research, testing, engineering and driver training at $193 million annually, but by this time the damage was done.

It was only after they’d been beaten up by RFK that it became clear to GM officials what they were up against. As one executive put it, automakers were now “targets of a disturbing, rapidly growing, and often fact-distorting campaign to indict motor vehicle design as the major contributor to traffic deaths and injuries.”

This was new territory for GM. In 1953, the company’s former president Charles E Wilson, nominated as Eisenhower’s secretary of defense, told his confirmation hearing: “For years I thought what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa. The difference did not exist. Our company is too big. It goes with the welfare of the country. Our contribution to the nation is quite considerable.”

A lot of interpretations have been offered for Wilson’s statement, but what he thought he was saying was that America and General Motors were on the same team, and should be looking out for each other’s interests. It was a single restatement of the Cold War consensus: a thriving commercial economy, centered around the automobile industry, would sustain America’s unsurpassed standards of living and geopolitical leadership. That commonality of interests no longer held.

General Motors stepped up its safety efforts, and its publicity of them, in the months following the hearings, and waited for the nation’s attention to shift back from highway death tolls to the gleaming new automobiles rolling off Detroit’s assembly lines. They were disappointed. Senators Kennedy and Ribicoff spent the rest of 1965 making speeches and writing articles on traffic safety and the failure of Detroit to produce a crashproof car.

The Senators’ criticisms were echoed by a growing chorus of tort lawyers. They’d filed over 100 suits alleging that the Chevrolet Corvair, General Motors’s innovative rear-engine compact, was so negligently designed that a gust of wind, a tight curve, or a bump in the road could cause a driver to lose control at speeds as low as 22 mph, resulting in severe injury or death. The lawyers were testifying at state legislatures that the Corvair was symptomatic of Detroit’s indifference to auto safety, and its willingness to sacrifice human life to pad its profits, and planting stories in tabloids about Chevrolet’s rear-engine “death trap.”

Amidst all this came the first notices of Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile. The book opened with gory details of Corvair traffic road accidents, and repeated arguments against the car used by lawyers suing GM. Nader called the Corvair one of the century’s “greatest acts of industrial irresponsibility,” and claimed GM could easily have made the car safe with a few dollars’ worth of safety improvements but was too greedy to pay for them.

The author went on to present Detroit’s executives as amoral and even sociopathic, determined to dazzle car buyers with expensive new paint colors and gadgets while installing weak brakes, fragile glass, unpadded dashboards, defective hood latches, sticky accelerators, inferior tires, and other faulty equipment. They got away with this, he maintained, because the auto industry operated outside the law, by which he meant free of federal regulation.

Kennedy’s attack on GM executives over safety spending got lengthy treatment. Like Ribicoff, Nader excoriated the “closely knit traffic safety establishment” for its close ties to the automakers. He even suggested an alarming conspiracy among medical professionals, police chiefs, insurance agents, auto-repair shops, funeral homes, and others whose financial interest is dependent on a steady supply of highway injuries and fatalities. Thousands of jobs depend on the death toll, said Nader: “[This] is where the remuneration lies and this is where the talent and energies go.”

Although much of Unsafe at Any Speed was generally tendentious, Nader did make valid points about Detroit’s methods and products. But in media appearances, and in his own star appearance before Ribicoff’s panel, Nader would occasionally go further than he had in the book, comparing American-built cars to sitting (as he told CBS, in 1966) “in a roomful of knives.” He would also present himself as a romantic figure, a lone wolf with few material possessions who lived in a cheap rooming house and did nothing but work. His ascetic lifestyle was accepted as proof of his devotion to the public good. His annual salary at Labor had been $15,000 (the national household income at the time was $6,590).

Weeks after the release of Nader’s book, tort lawyers brought the safety crusade to a new pitch with their Stop Murder by Motor publicity campaign. Their use of the word “murder” echoed Nader’s oft-made suggestion that there had to be something deliberate about Detroit’s creation of such lethal vehicles. Ribicoff, Moynihan, Kennedy, and even President Johnson all endorsed the campaign.

GM officials were bewildered at the animus now directed toward their company, and alarmed that Senators Ribicoff, Kennedy, and Moynihan, Nader, the Corvair plaintiffs, and the defense bar were apparently sharing information and arguments, and collaborating on tactics.

Nader, who worked for Ribicoff and Moynihan, and who was known to share his research with tort lawyers, seemed to be at the center of the cabal, but no one knew much about him. He claimed to be a lone wolf but he was employed inside the government, and had better connections in many quarters than GM itself. He was trained as a lawyer but he’d apparently abandoned the practice. He’d written a book but did not present as a journalist. Was he a political actor? A consultant? Was he setting himself up as an expert witness?

He was all around GM but the company couldn’t get a bead on him. “Who the hell is this guy?” one GM attorney asked his colleagues.

No one individual at General Motors would ever claim credit for the idea, but by the end of 1965, the company had laid plans to hire an investigator. The brief was to discover Nader’s angle, and dig up any available dirt on him. It was a stupid move.

GM’s investigators did some legitimate work, turning up solid information about Nader’s connection to the tort lawyers, his handsome salary at Labor, his purchase of Ford stock previous to GM’s appearance before Ribicoff, and that he was playing both sides of the table for the Senator, posing as an independent witness before the Senate subcommittee while also helping to direct the hearings. They also came close to learning that Nader had written his book on the public payroll, and that Moynihan and the Labor department were effectively paying him, long after his original report had been filed, to support the Senate subcommittee.

But the investigators, pretending to be checking Nader out for a prospective employer, also asked friends and acquaintances about his personal life and habits. This and other missteps raised suspicions, causing the detectives to be outed. GM’s executives were called back before the Ribicoff panel. They issued a humiliating apology and lost whatever support remained for the company in Washington.

The Johnson administration proposed to create a new department of transportation, and bring General Motors and the rest of Detroit under federal regulation to set standards for auto safety. Something had to be done, he said, echoing Nader’s arguments with the statement that “there is no single statistic of American life more shocking than the toll of dead and injured on our highways.”

Senators and congressmen fought with one another to make Johnson’s two pieces of auto safety legislation as stringent as possible, and to pass them before the November 1966 midterm elections.

Elizabeth Drew, writing in the Atlantic Monthly, was stunned by the “radical departure from the government’s traditional, respectful hands-off approach” to the auto industry. She attributed the change not to any deep concern with auto safety, but rather to the realization that “automobile safety was good politics.” People loved their cars but nobody really loved an automobile company and the result had been “a political car-safety derby, with politicians jockeying for the position out in front.”

Congressmen interviewed by Dan Cordtz, who covered the story for Fortune, showed little interest in the complicated problem of traffic safety or the merits of second-collision theory. They voted not to address a public-policy problem but to punish GM for its poor performance before Ribicoff’s committee and spying on Nader. Wrote Cordtz, “Many strong supporters of auto safety legislation agree that G.M.’s conduct … was the most important single factor in establishing a congressional climate conducive to the passage of a tough safety bill.”

None of what I write here is intended to whitewash or excuse GM’s behavior, or that of the corporate sector more generally. General Motors had a history of bullying and predatory behavior. Its definition of the public good, while broader than recognized at the time, was too narrow for its own good. And it deserved to get slapped around in the public sphere for using private investigators to seek personal dirt on Nader.

But that is no alibi for Congress to approve hasty, sweeping, punitive and counterproductive regulations of America’s most important industry. Any decision on federal involvement in the auto industry should have been made on the merits of the proposed legislation. Yet the legislators displayed minimal curiosity about safety issues. They were primarily interested in taking down a corporate giant and the fight for legislative credit. They were as reckless in their treatment of Detroit as Nader and friends imagined automakers to be in their treatment of consumers.

Johnson’s National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act of 1966 was deliberately conceived so as to shift the focus of America’s concern for road safety from drivers to vehicles. As directed, the newly formed National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) was primarily concerned with the crashworthiness of automobiles, and soon imposed more than 50 vehicle safety standards on automakers. It also won the ability to force recalls on automakers. The focus of the NHTSA became even narrower when President Jimmy Carter appointed Nader’s colleague Joan Claybrook as its head. Air bags, the holy grail of those bent on crashproof vehicles, became the overwhelming focus of the agency’s efforts, though the technology was still not ready and claims for their efficacy were still being exaggerated.

Nader and the safety crusaders opened the floodgates for other enterprising congressmen to campaign against corporate recklessness. The 25 consumer and environmental regulatory bills passed in the wake of the traffic safety bills expanded the regulatory state into food, cosmetics, credit instruments, packaging and advertising, monopolies and pricing practices, and air and water pollution. The number of people staffing federal regulatory agencies tripled, and government spending on regulatory enforcement increased by a factor of nine over roughly the same period. Additionally, by 1975, all 50 states had created their own consumer-protection agencies and 39 had passed consumer protection statutes.

These congressmen were joined in Washington by a new generation of activists. By 1977, 83 public interest groups were operating in the capital, more than half of them arriving after Nader’s triumph.

Meanwhile, the courts curtailed legal defenses available to manufacturers while expanding liability standards to cover almost any product malfunction. They also allowed greater scope for recovery of non-economic damages such as pain and suffering, and permitted class-action procedures by which private law claims could be aggregated by the hundreds of thousands, effectively industrialized torts. All of these measures were a boon to entrepreneurial attorneys arguing harms on behalf of the victimized American consumer. From 1950 to 1990, direct tort costs grew at an astonishing average annual rate of 11.3 percent, from $1.8 billion a year to $130.2 billion, more than three times the rate of growth in the economy.

Altogether, these congressmen, lawyers, and activists represented an enormous shift in America’s entrepreneurial energies, from economic growth to identifying and combatting growth’s negative consequences. Or, as author Robert Gordon put it, from creating goods to fighting bads. This was the end of American enterprise in the form it had taken for the first 200 years of the country’s history.

It happened with breathtaking speed. In 1964, historian Richard Hofstadter had written that “the existence and workings of the corporations are largely accepted, and in the main they are assumed to be fundamentally benign.” Public approval of business peaked in 1966, when 55 percent of surveyed Americans expressed “a great deal of confidence“ in the leaders of major corporations, and 96 percent agreed that free enterprise had made America great. By 1971, only 27 percent of Americans expressed a great deal of confidence in business leadership. And by 1974, the figure was just 16 percent.

Sales of the Corvair collapsed by two-thirds, even before GM’s private eyes were discovered. It was out of production entirely within two years, despite the fact that the suits against the Corvair were either lost, dropped, or settled out of court for low amounts.

Nader has never admitted that his characterization of the car was uniquely dangerous and negligently designed was wrong, even after a court case vindicated the car’s design. The NHTSA, under pressure from Nader, subjected the car to intensive testing and found “the handling and stability performance of the … Corvair does not result in an abnormal potential for loss of control or rollover and it is at least as good as the performance of some contemporary vehicles both foreign and domestic.”

And while the fate of this single rear-engine compact car alone was insufficient to change the future of GM, the safety crusade did severe damage to the company’s overall brand. In 1965, GM was comfortably atop the Fortune 500 rankings, and its new model year had broken all records for sales volume, revenue, and profits. Independent consumer surveys showed that GM was considered by Americans the undisputed leader of the auto industry, and easily the most powerful, successful, and admired US corporation. Gallup found GM ahead of every other American firm in terms of products, corporate performance, and contributions to society. Safety was not a serious issue in the public mind. Americans blamed bad drivers for blood on the road and believed their cars were built with their protection in mind.

All that changed with the confluence of Ribicoff’s hearings, the publication of Unsafe at Any Speed, the Stop Murder by Motor campaign, and leaked news that the White House was preparing a bill to regulate automakers. In February 1966 (a month before GM’s detectives were discovered), GM sales dropped precipitously. Nearly every GM nameplate was affected, and the corporation’s reversal was enough to drag the whole industry into a net decline, the first significant break in a remarkable five-year run for Detroit. Despite widespread discounting of GM models, sales were off eight percent by the end of the year.

The damage was reflected in GM’s share price, the most important metric so far as management was concerned. It hit a high of $105 in the first weeks of 1966, dropped to $101 on the release of early February sales data, and fell to $95 after GM’s detectives were exposed. By the end of 1966, it traded at $66, representing a 37 percent loss in shareholder value for the market’s most reliable performer.

The familiar narrative of Detroit’s decline takes the 1973 oil crisis as a critical juncture. A sudden surge in oil prices that year prompted a large number of American car buyers to abandon Detroit’s massive and expensive cars for smaller, more fuel-efficient imports from Japan and Germany. American manufacturers were blind to the inferior quality of their vehicles, failed to meet the challenge, and imports took over the American market.

But imports had begun trending up sharply in 1966, right around the time when Ribicoff and Nader opened their campaign to convince Americans that Detroit was murdering them with unsafe vehicles. This happened despite these imports’ being generally less safe and of poorer quality than American-made cars. (The real advances in Japanese manufacturing, led by Honda, came in the late 1970s.)

Why didn’t Detroit introduce hot new compacts to beat back the foreign invasion? That’s what they’d done in the late 1950s, when the Volkswagen Beetle led an import push that peaked at 12 percent of the US market. GM announced the compact Corvair, while Ford and Chrysler introduced compacts of their own. And imports trended downward in the early 1960s (though the stalwart Beetle did remain popular).

In 1970, US car companies again tried to respond, this time with innovative four-cylinder vehicles, led by Chevrolet’s Vega. But the business environment had changed markedly during the preceding decade. GM, now dealing with slimmer profits and a lower share price, had become risk averse following the relentless attacks on its innovative rear-engine Corvair. Its finances were now so weak that new cars had be designed and built on the cheap, and it showed.

After 1966, General Motors was like an automobile that had been returned to the road after a bad crash. It looked okay from the outside, but never ran properly again. The stability, confidence, and consistent growth it had enjoyed up until 1966 would never return. And because GM comprised half of the domestic auto industry, Detroit was never the same, either.

In 1960, GM had begun investing vast sums of money in overseas expansion, with the underlying goal of dominating world auto markets. Its executives made a series of speeches on the changing nature of global commerce, and about how the United States needed to lift its head from the domestic scene if it was to hold its position of leadership in the markets of tomorrow. Donner, the company chair, wanted his government and international trade bodies to foster a global business environment that encouraged private investment and the free movement of capital, with a reduction in punitive taxation and trade barriers.

Instead of executing this global plan, Donner’s company spent the next decade at war with Washington over safety and environmental standards. Instead of helping automakers with their ambitions, as governments in Japan and Germany were helping their own domestic manufacturers, President Johnson, anxious to reduce a US foreign trade deficit (largely of his own making), signed an executive order prohibiting US investors from acquiring more than 10 percent of foreign businesses. Thus was the world car market cleared for Japan and Germany.

There is no arguing with Ralph Nader, and every other safety crusader, that the 49,163 fatalities on American roads in 1965, the last year before passage of Johnson’s traffic safety legislation, were a public-health catastrophe. Reducing the death toll was a perfectly legitimate goal of public policy. The question remains, did the safety crusaders solve the problem, or at least save more lives than would have been saved without their intervention?

Nader and the NHTSA claim that the legislative and regulatory apparatus created in 1966 saved 3.5 million lives during the 50-year period that followed, with the NHTSA calling it “one of the most effective public health and safety efforts of the past century.” But the data does not support this claim. Statistically speaking, there was more safety progress in the half-century before the 1966 legislation than in the half-century that followed. Moreover, that 3.5-million figure includes fatality reductions that are unrelated to vehicle-safety technology, such as those associated with mandatory seatbelt usage and drunk-driving laws.

Seatbelts alone are credited by contemporary researchers with saving more lives than all other vehicle safety technologies put together, between 1960 and 2021. These devices were installed pre-1966 by automakers under pressure from state legislatures (part of the maligned “traffic-safety establishment”). But few people used them. Congress could have made them mandatory, but lacked the courage to impose their use on the nation’s drivers.

This was one of the more invidious effects of second-collision theory: The rush to blame Detroit for traffic deaths gave drivers a free pass. In fact, Nader himself vociferously opposed mandatory seatbelt usage on the grounds that people were incorrigible and behavior-control laws would never work. “We learned that in prohibition,” he told a government hearing in 1983. As for drunk driving, he told a journalist that he was skeptical of prohibiting that, too, because “the culture is deeply embedded. I thought it was too ingrained.”

Of the many new safety standards applied by NHTSA to American cars, in fact, the most effective were instigated before 1966 by the unheralded regulators in the GSA who’d rather quietly used their purchasing power to nudge Detroit to hurry along its improvements. The energy-absorbing steering column (credited with saving 79,989 lives between 1960 and 2012, second only to seat belts on the list of life-saving technologies), upgrades to instrument panels (34,477 lives), modified windshield glass (9,853 lives), and improved door locks (42,135 lives) all predated the legislation.

The NHTSA can legitimately take credit for airbags, which it championed relentlessly. They are estimated to have saved 76,114 lives between 1960 and 2012. That’s progress. But more than 90 percent of accidents are caused by human error of one kind or another. As recently as 1982, more than 60 percent of all US traffic fatalities were alcohol-related, as compared to less than half of that today. And so the beneficial effects of NHTSA regulations arguably have been offset by the number of lives lost thanks to the federal government’s emphasis on the crashworthiness of cars rather than the behavior of drivers.

America once had the safest roads in the world. But in the wake of Unsafe at Any Speed and the passage of the 1966 legislation, countries that moved more quickly toward mandatory seatbelts and against drunk driving, including Canada, Australia, and Great Britain, each reduced their annual fatality counts more quickly. In a 2014 published study of traffic fatality rates in 25 countries between 1972 and 2011, the United States was found to be a “unique outlier,” with by far the lowest rate of traffic-fatality decline among the entire group. In 1972, the United States and the Netherlands both reached their peak traffic fatality rates. Over the next three decades, U.S. deaths declined by 41 percent. In the Netherlands, the corresponding figure was 81 percent.

If, in 1966, Congress had told the driving public to sober up, buckle up, and drive right, rather than pursuing a largely political campaign against Detroit, regulators would have something to boast about. But in truth, Ralph Nader and the federal government actually seem to have harmed the cause of traffic safety.

Regulation has its place, in the economy generally, and in the auto industry particularly. There was a legitimate role for Washington in the field of traffic safety in the 1960s. Manufacturers had done more to make vehicles safe than the likes of Nader would acknowledge, but there were limits to how much safety consumers were willing to buy. This was a market failure, and market failures are where regulators step in. The GSA did step in, with a light-touch and effective regulatory approach that should have been built upon.

The National Safety Council made this point to Ribicoff’s committee, insisting that the federal government already had all the power it needed if its goal was to improve auto safety. With easily the most comprehensive and cogently argued presentation that Ribicoff heard—albeit one delivered to an empty hearing room—the council noted that the traffic-safety establishment had supported the GSA’s intervention on car interiors, while at the same time warning that second-collision theory was not a magic bullet. There was no such thing as a crashproof vehicle. The greatest strides in traffic safety, the council insisted, had been made through road-engineering and driver-behavior measures. The council wanted politicians to move on mandatory seatbelt usage and drunk-driving laws, another form of regulation. But that would have required Congress to impose their will on voters rather than on Detroit; and so Ribicoff wanted nothing to do with the idea.

Quietly enforced, reasonable regulatory measures, were never going to satisfy the crusaders of 1966 because most of them had goals extending beyond the problem of saving lives in traffic. They wanted to stop Americans from caring so much about their damned automobiles and turn their attention to other purposes. They hoped to change minds about how far government should intervene in the economy, and sought to undermine the veneration of business leaders and the gigantic enterprises they’d built. If they could also further their own electoral prospects and the Great Society legislative record, all the better.

What lessons does this have for tech in 2021? Perhaps you have noticed some similarities between the rise of the automobile and the rise of the Internet in American life.

The automobile was largely a product of American commercial genius, wholeheartedly embraced by the American people as a tool for the advancement of personal, social, and economic welfare. Automobile culture quickly became American culture, and it remade the nation top to bottom without any involvement by the federal government beyond cheerleading and roadbuilding.

The automobilization of America continued until the wonders of driving grew familiar, automakers became huge and powerful, and the adverse consequences of car culture and the larger commercial economy to which it was central became more apparent. Critics of the automobile grew in number and eventually focused their criticisms not on the driving public or the national government that had funded the highways (and early in its history refused the role of regulator), but the greedy corporate entities purportedly harming the populace in a profit-driven project.

It echoes, no?

And many of the fundamental elements remain unchanged since 1966. There are plenty of enterprising congressmen, lawyers, and activists anxious to bring big tech to heel, heaping upon it blame for every ill associated with the Internet. As Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg has demonstrated during his visits to Congress, today’s tech executives are often as easily tripped up by grandstanding politicians as were their auto-executive forebears. And in time, the fate of their enterprises may well follow the same downward arc that Ralph Nader and Abraham Ribicoff helped inflict on Detroit.

This essay is adapted in part from the author's newly published book, The Sack of Detroit: General Motors and the End of American Enterprise