Bioethics

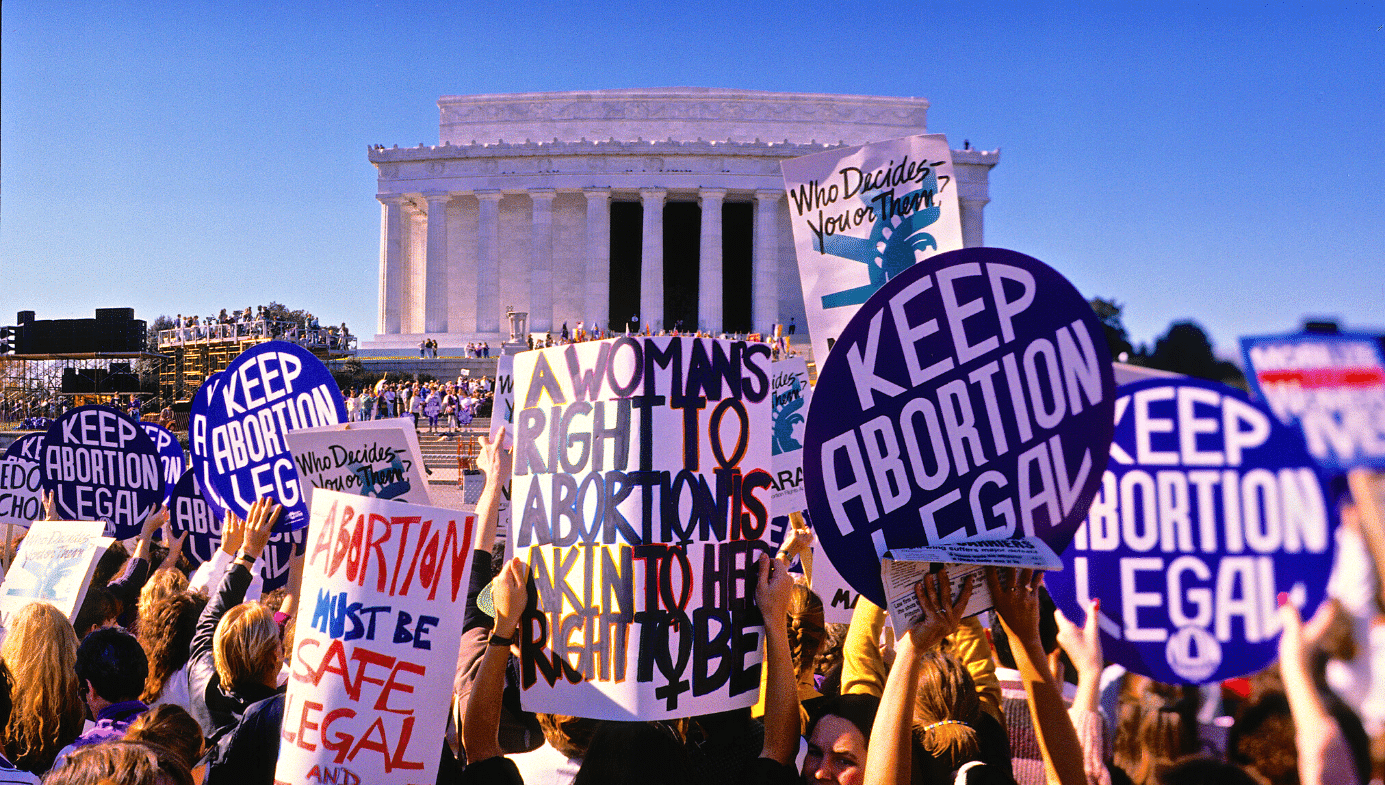

The Moral Panic about Eugenics Poses a Threat to Abortion Rights

One of the reasons abortion bans on the basis of prenatal diagnoses may have received relatively little attention is because they leave the pro-choice Left in an uncomfortable ethical position.

American partisan politics has just been inflamed by implementation of a Texas ban on abortions once an embryo’s heartbeat is detected, usually after the sixth week of pregnancy. The new law gets around Roe v Wade by making it possible for anyone to charge a person who helps a woman terminate her pregnancy, from Uber drivers to doctors. But it’s unclear if the Texas abortion ban will stick, and bans on the basis of “anti-eugenic” rhetoric may be more likely to pose a risk to abortion rights. “Prenatal Nondiscrimination Acts” (PRENDA) and other bans which prevent women from getting abortions on the basis of a prenatal diagnosis of disability have been gaining traction throughout the United States. As Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas has said, the States might not be allowed to lawfully protect “eugenic abortions,” which Harvard scholar Michael Stokes Paulsen has described as “the deliberate killing of children with a disability because of their disability.”

Fundamentally, eugenics is any intervention, whether chosen by the individual or by the state, which aims to decrease the number of people with disabilities and increase the number of people with qualities that are generally considered valuable, like health, intelligence, and attractiveness. Scholars have distinguished between “old eugenics”—interventions like state-sponsored sterilization and banning relatives from marrying—and “contemporary eugenics” or “velvet eugenics.” These new forms of eugenics represent the commercialization of eugenic ideas, which are then implemented by individuals rather than enacted by the state or another authoritative body.

One of the reasons abortion bans on the basis of prenatal diagnoses may have received relatively little attention is because they leave the pro-choice Left in an uncomfortable ethical position. The view that a woman has a right to an abortion for any reason is fundamentally at odds with an anti-eugenic stance. For 40 years, the Left has waged a war against eugenics which has now given ammunition to those who want to restrict or criminalize abortion. The conversation about eugenics itself has been hopelessly muddled by the constant accusation of eugenics against people, technologies, and policies, making clear thinking on this important ethical issue in the public sphere nearly impossible.

How widespread are bans against women aborting on the basis of genetic or congenital disability? Six states—Mississippi, Missouri, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Tennessee—have prohibited abortion on the grounds of a genetic diagnosis of disability, although others like Florida have attempted to implement such bans. Bans are only one way of preventing these kinds of abortions. In states like Arizona, Minnesota, and Oklahoma, women who seek an abortion because their baby will die within hours or days of birth are required to be notified of the availability of perinatal hospice, which may nudge women to deliver a baby with a lethal abnormality. Other states require women to be counseled on the medical condition or disability of their fetus. And in a few states, doctors are prevented from mentioning abortion as an option when women are informed their fetus is likely to have a severe disability. These laws will be difficult to enforce because, for instance, they require abortion providers to ask women why they wish to terminate their pregnancies or impose on otherwise private conversations. But as one conservative activist said, “Even if it’s hard to enforce, it’s worth being passed. It’s important for a state to show they are not supporting eugenics.”

Many progressives have objected that the choices individual women make about whether or not to have an abortion do not constitute eugenics. But these bans and the moral confusion surrounding abortion are among the many troubling outcomes of the Left’s moral panic about eugenics. In the 1970s, the sociobiologist E.O. Wilson suggested that, in the future, “greater knowledge of human heredity” could provide us with “democratically contrived eugenics.” Wilson was probably right. However, this sentence, along with his biological view of human nature, have made him an extraordinarily controversial figure to this day.

Forty years later, we are still having the same conversations about what is and what is not eugenics. Forty years later, scientists continually feel the need to defend themselves against charges of eugenics from the Left while they themselves use eugenics to discredit ideas and scientists they find problematic. Fields and concepts as disparate as IQ, BMI, behavioral genetics, and even statistical analysis itself have been labeled as eugenics. Anecdotally, when I co-authored a paper that attempted to clarify the conversation around eugenics, it was attacked as immoral and beneath consideration. In an environment where many of the intelligentsia are attempting to avoid charges of eugenics and lob charges of eugenics at others, it’s no wonder these conversations have become so incendiary and pointlessly confusing.

The Left’s tendency to call so many things they don’t like eugenics, combined with the taboo against discussing eugenics in any meaningful way, has made the public conversation about the topic incoherent. Even as progressives maintain that abortion on the basis of disability is not eugenics, they have criticized many other individual choices as eugenics. For example, in 2019 George Church discussed his plans to make a genetic matchmaking app, digid8, which would prevent people with rare genetic diseases from meeting each other. This would diminish the risk of passing a disability onto their offspring (a similar approach to that used by Dor Yeshorim). This private company’s service—which people would have to opt into and pay for—caused huge controversy over its eugenic implications. Another individual choice, using genetic screening to choose an embryo to implant during invitro fertilization (IVF), is also widely associated with eugenics, especially if parents select for cosmetic features like eye color. If the individual choice of using a dating app or engaging in embryo selection is eugenics, certainly the individual choice to terminate a pregnancy on the basis of disability also fits this definition.

Although the majority of abortions are chosen due to the financial, social, and other burdens of an unplanned pregnancy, eugenic abortions are not uncommon. Around two to three percent of pregnancies in industrialized countries like the US are affected by a birth defect or congenital abnormality. Of these, a significant number result in abortion. For example, when parents are carriers for cystic fibrosis, they terminate pregnancies screened positive for this disease 95 percent of the time. In the developed world, fetuses diagnosed with spina bifida are terminated 63 percent of the time, and 83 percent of fetuses diagnosed with anencephaly are aborted. In the case of Down syndrome, the US has one of the lowest rates of termination at 67 percent. But in other developed countries, the rate is 90 percent or higher. Even in the case of unplanned pregnancies, usually terminated without prenatal screening, five percent of women chose abortion citing concerns about the health of the fetus. According to one woman who sought an abortion, “The medication I’m on for bipolar disorder is known to cause birth defects and we decided it’s akin to child abuse if you know you’re bringing your child into the world with a higher risk for things.”

To add to the confusion about the term, many on the Left have embraced the idea that some forms of discrimination against black people and women is eugenic because some of the eugenics interventions of the 20th century targeted black women for sterilization. This is another domain in which the label of eugenics is being incoherently applied. For example, Project Prevention is an organization that pays women who are addicted to drugs and alcohol $300, plus medical fees and follow up visits, to go on long-term birth control. These women can choose whether to get an IUD, a hormonal implant, or surgical sterilization. One of the main reasons critics have called Project Prevention eugenic is that 20 percent of Project Prevention clients are black. But black women choose abortion even more disproportionately. More than a third of all abortions are among black women. Does the chance to get $300 and free medical care really make only one of these choices eugenics? According to Michael Stokes Paulsen:

Does unrestricted legal abortion-choice produce a disparate impact resulting in disproportionate numbers of abortions ending the lives of minority, female, and disabled fetuses? Undeniably. The aborted are disproportionately Black, female, and disabled. Is the right to abortion sometimes used, by those exercising the abortion-choice, for eugenics purposes—specifically for the purpose of aborting on the basis of race, sex, or disability? Unquestionably. [Emphasis in original.]

By the same anti-eugenics logic of disparate impact on minorities and women, abortion is eugenic. Furthermore, an intervention that could reduce the number of black women seeking abortions, providing them incentives or free contraception, would be a nonstarter on the Right because it would offer free birth control, and a nonstarter on the Left because it would be considered racist and eugenics.

Although old eugenics is thought to be wildly unpopular (but may not be), the evidence of the popularity of contemporary eugenics is evident from how readily the public have taken it up. Many of eugenics’s staunchest opponents on the Left not only don’t appreciate the extent to which abortion is eugenic, they also don’t realize the extent to which the standard of prenatal care in the developed world is transparently eugenic in its aims. Routine prenatal care in the United States—ultrasounds checking for normal anatomy, recommended genetic screening for women with a family history of specific heritable disorders and women over 35 and so on—are, to a great extent, intended to demonstrate that the unborn child is free from abnormality, malformation, or disability.

For example, the nuchal translucency scan, provided to nearly every pregnant woman in the developed world regardless of risk, measures fluid buildup in the fetus which can indicate whether the child will have congenital heart defects, Down syndrome, or other impairments. Some parents who receive these tests simply want to be prepared for any possible health conditions or disabilities in the child. But most parents receive these screenings with the intention of terminating the pregnancy of a child that is likely to have cognitive, physical, or other disabilities. Because of the bioethical implications, disability activist Rosemarie Garland-Thomson has endorsed the idea that we should stop engaging in routine prenatal testing “for any conditions, except very, very carefully identified and adjudicated conditions that really are terrible, that really are incompatible with life.” Finally, a 2019 study found that 22.6 percent of women who were against abortion changed their minds when faced with medical complications. So, the judgement against abortion on the basis of fetal disability comes down, to some extent, to good luck.

The view that a woman has an a priori right to an abortion results in some strange bioethical consequences. Even though it doesn’t really fit the actual definition of eugenics, choosing the sex of a child—either by picking a male or female embryo or by sperm sorting—has been associated with eugenics and banned in countries like the UK, Australia, and Canada. Ironically, in some countries, sex selection is only allowed if a disability, like muscular dystrophy, is sex-linked, which means you’re only allowed to practice sex selection in the name of eugenics. A woman in Canada, meanwhile, would not be allowed to choose an embryo of a particular sex to implant using IVF, but would be allowed to have an abortion because she didn’t want to have a girl.

Something similar could happen with a new technique called polygenic screening (PGS), a way of screening embryos for characteristics determined by multiple genes. Polygenic screening, you guessed it, has been widely attacked as eugenic. At the moment, a woman using in vitro fertilization can screen her embryos with PGS and pick the embryo with the lowest risk of schizophrenia or diabetes. But it’s possible that in the future, women in many countries might not be allowed to use PGS to select an embryo with specific characteristics they desire, but they might be able to undergo prenatal tests that would provide them with the same information (see here for an example of using prenatal testing to sequence an embryo’s whole genome). That means a woman might not be permitted to select an embryo without diabetes using PGS, but would be allowed to have an abortion if prenatal testing reveals that her child is likely to have diabetes.

Many of the arguments against eugenics rest on the claim that exceptions are a slippery slope—that classifying some personal attributes and disorders as desirable or undesirable, respectively, will inevitably lead to the mistreatment of disabled people or genocide. But this hasn’t been the case in countries like Denmark and Israel, where the state pays for prenatal testing, abortions in the case of fetal abnormality, and generous benefits for their disabled citizens. And if eugenics truly is a slippery slope, then the Left should join the Right in enforcing bans on abortion in the case of fetal disability and abnormality.

In particular, a coherent anti-eugenic stance would require the Left to align themselves with the Right’s intention to limit the number of weeks a woman is allowed to terminate a pregnancy. Bans on abortion after 10 or 20 weeks disproportionately impact women who seek to terminate a pregnancy because of fetal abnormalities, as testing usually occurs between weeks 10 and 15 of pregnancy. As Garland-Thomson argues, abortion without any information about the fetus is less ethically problematic. Those who are consistently anti-eugenics should endorse bans after week 10 of pregnancy, because it ensures that women are terminating their pregnancy for reasons that are unlikely to be related to fetal disorder.

It is ethically incoherent to be against all forms of eugenics and also allow a woman to choose to terminate a pregnancy for any reason, including the discovery of genetic abnormality. But the Left has become entangled in a contradiction of its own making. It created a moral panic and used denunciation to shut down discussion of what forms of eugenics may or may not be permissible. This tars many different forms of voluntary reproductive intervention with the same brush as state-mandated sterilization and genocide. Ultimately, the dismal state of progressive discourse about eugenics may produce regressive outcomes—it is already being used to prevent the implementation of new reproductive technologies, and it may end up further costing women their reproductive freedom.