Violence

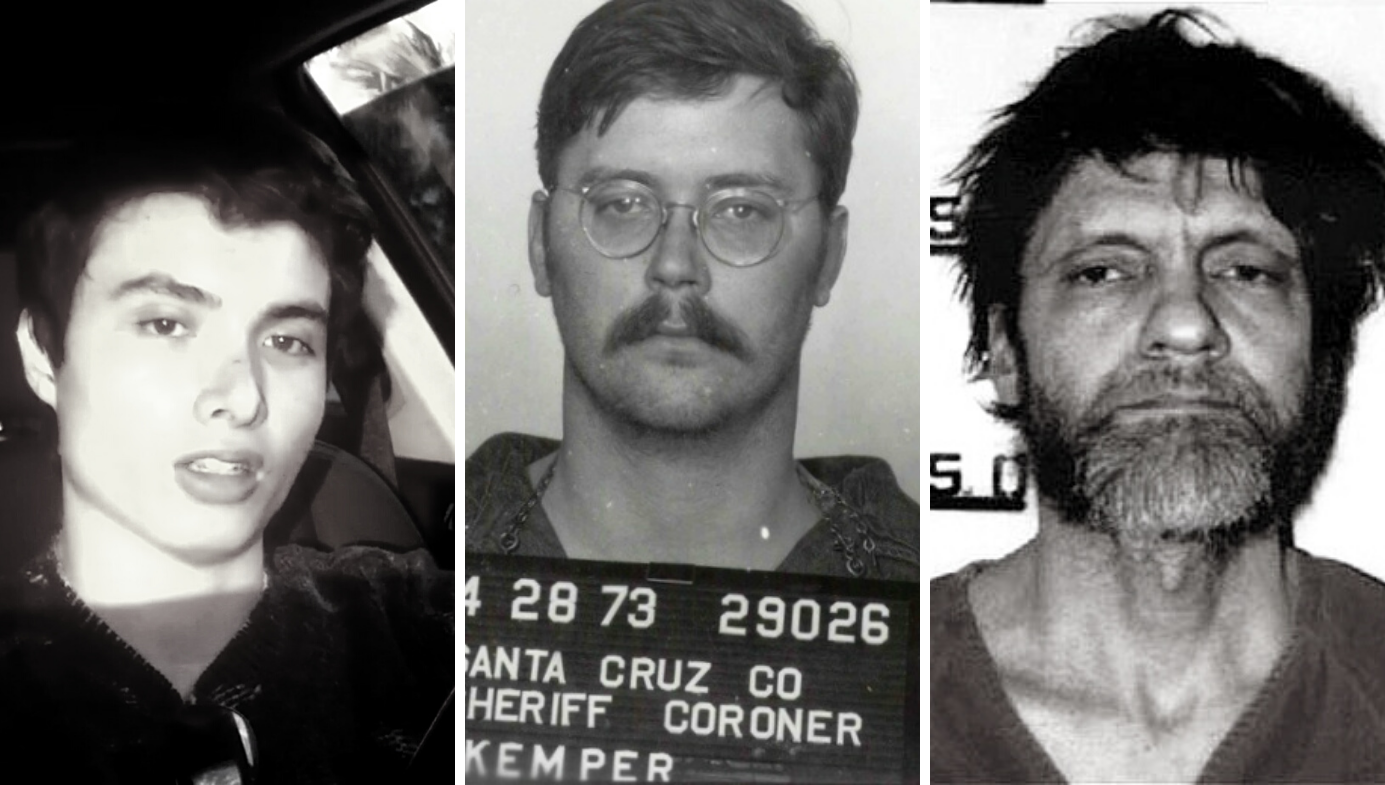

The Status Game: Male, Grandiose, Humiliated

The logic of the status game dictates that humiliation must be uniquely catastrophic.

Elliot was 11 years old and playing happily at summer camp when he accidentally bumped into a pretty and popular girl. “She got very angry,” he recounted later. “She cursed at me and pushed me.” He froze, shocked, completely lost as to how to respond. Everybody was watching. “Are you okay?” asked one of his friends. Elliot couldn’t speak or move. He felt humiliated. He barely talked for the rest of the day. “I couldn’t believe what had happened.” The experience made him feel like an “insignificant, unworthy little mouse. I felt so small and vulnerable. I couldn’t believe this girl was so horrible to me, and I thought it was because she viewed me as a loser.” As he grew into his teens, continually rejected and bullied by the cool school elites, Elliot never forgot the incident. “It would scar me for life.”

Ted was a gifted scholar, arriving at Harvard University at age 16. One day, he applied to take part in an experiment led by the prestigious psychologist Professor Henry Murray. Ted was instructed to spend a month writing an “exposition of your personal philosophy of life, an affirmation of the major guiding principles in accord with which you live or hope to live” and an autobiography containing deeply personal information about subjects including toilet training, thumb sucking, and masturbation. What Ted didn’t know was that Murray had a history of working on behalf of secretive government agencies. This would be a study of harsh interrogation techniques, specifically the “effects of emotional and psychological trauma on unwitting human subjects.” Once he’d detailed his secrets and philosophies, Ted was led into a brightly lit room, had wires and probes attached to him, and was sat in front of a one way mirror. There began a series of what Murray called “vehement, sweeping, and personally abusive” attacks on his personal history and the rules and symbols by which he lived and hoped to live. “Every week for three years, someone met with him to verbally abuse him and humiliate him,” Ted’s brother said. “He never told us about the experiments, but we noticed how he changed.” Ted himself described the humiliation experiments as “the worst experience of my life.”

Ed grew up with an abusive mother. She was an alcoholic and paranoid and “extremely domineering.” She’d berate him in public and refuse him affection for fear it would turn him gay. Large for his age, when Ed was 10 she became obsessed with the idea he’d molest his sister, so she locked him in the basement to sleep. He spent months down there, the only exit a trapdoor under the space where the kitchen table usually stood. She’d frequently belittle him, telling him none of the smart, beautiful young women at the university where she worked would go near him. His was a childhood of rejection and humiliation. “I had this love hate complex with my mother that was very hard for me to handle,” he said. This “hassle” with his mother made him feel “very inadequate around women, because they posed a threat to me. Inside I blew them up very large. You know, the little games women play, I couldn’t play [or] meet their demands. So I backslid.”

Ed backslid. He really did. He killed his grandmother, “because I wanted to kill my mother.” Then he killed his mother. He cut off her head and had sex with it, then buried it in the garden, eyes facing upwards because she always wanted people to “look up to her.” He also killed eight other women, having sex with some of their corpses and eating others. Ed Kemper remains one of America’s most notorious serial killers. Elliot Rodger, meanwhile, became a spree killer, killing six young people and then himself at the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 2014. And Ted? That’s Ted Kaczynski. The Unabomber.

If life is a status game, what happens when all our status is taken from us? What happens when we’re made to feel like nothing, again and again and again? Humiliation can be seen as the opposite of status, the hell to its heaven. Like status, humiliation comes from other people. Like status, it involves their judgement of our place in the social rankings. Like status, the higher they sit in the rankings, and the more of them there are, the more powerful their judgement. And, like status, it matters. Humiliation has been described by researchers as “the nuclear bomb of the emotions” and has been shown to cause major depressions, suicidal states, psychosis, extreme rage, and severe anxiety, “including ones characteristic of post traumatic stress disorder.” Criminal violence expert Professor James Gilligan describes the experience of humiliation as an “annihilation of the self.” His decades of research in prisons and prison hospitals, seeking the causes of violence, led him to “a psychological truth exemplified by the fact that one after another of the most violent men I have worked with over the years have described to me how they had been humiliated repeatedly throughout their childhoods.”

The logic of the status game dictates that humiliation must be uniquely catastrophic. For psychologists Professor Raymond Bergner and Dr Walter Torres humiliation is an absolute purging of status and the ability to claim it. They propose four preconditions for an episode to count as humiliating. Firstly, we should believe, as most of us do, that we’re deserving of status. Secondly, humiliating incidents are public. Thirdly, the person doing the degrading must themselves have some modicum of status. And finally, the stinger: the “rejection of the status to claim status.” Or, from our perspective, rejection from the status game entirely.

In severe states of humiliation, we tumble so spectacularly down the rankings that we’re no longer considered a useful co-player. So we’re gone, exiled, cancelled. Connection to our kin is severed. “The critical nature of this element is hard to overstate,” they write. “When humiliation annuls the status of individuals to claim status, they are in essence denied eligibility to recover the status they have lost.” If humans are players, programmed to seek connection and status, humiliation insults both our deepest needs. And there’s nothing we can do about it. “They have effectively lost the voice to make claims within the relevant community and especially to make counterclaims on their own behalf to remove their humiliation.” The only way to recover is to find a new game even if that means rebuilding an entire life and self. “Many humiliated individuals find it necessary to move to another community to recover their status, or more broadly, to reconstruct their lives.”

But there is one other option. An African proverb says, “the child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.” If the game rejects you, you can return in dominance as a vengeful god, using deadly violence to force the game to attend to you in humility. The life’s work of Professor Gilligan led him to conclude the fundamental cause of most human violence is the “wish to ward off or eliminate the feeling of shame and humiliation and replace it with its opposite, the feeling of pride.”

Of course, it would be naive to claim Ed, Ted, and Elliot were triggered solely as a response to humiliation. If the cauterisation of status was a simple mass killing switch, such crimes would be common. Various further contributory factors are possible. All three were men, which dramatically increases the likelihood they’d seek to restore their lost status with violence. Elliot Rodger was said to be on the autism spectrum, which might’ve impacted his ability to make friends and girlfriends; a court psychiatrist claimed Ed Kemper had paranoid schizophrenia (although this remains contested); and Kaczynski’s brother said Ted once “showed indications of schizophrenia.” But none of these conditions are answers in themselves, because the vast majority of those that have them don’t burn down their villages.

And that’s what happened. All three attacked the status games from which they felt rejected, asserting their dominance over their degraders. Ed Kemper’s mother would taunt her son with her belief that the high status co ed girls at her university would never date him. He began killing those girls, becoming the “Co Ed Killer,” before finishing with his mother: “I cut off her head and I humiliated her corpse.” He then pushed her voice box into the food disposal unit. “It seemed appropriate as much as she’d bitched and screamed and yelled at me over so many years.” Kemper’s psychological profiler at the FBI, John Douglas, writes: “He was a man on a mission who’d had humiliating experiences with women and was now out to punish as many as he could,” adding he was “someone not born a serial killer but manufactured as one.”

Ted Kaczynski, who’d been humiliated by a prestigious scientist at Harvard, became the “Unabomber,” the “un” standing for the universities that were partly his target. His brain took his feelings of debasement and resentment and magicked them into a story in which he was the hero. He went to war against smart people and the world they’d made, writing that the technological age and its consequences have “been a disaster for the human race” and have “made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering.” His bombing campaign was the start of a revolution, aimed at freeing the masses from slavery by “the system.” He sought and received, in return for a promissory cessation of violence, the extraordinarily statusful experience of having his 35,000 word exposition on modernity’s evils published by the Washington Post.

And Elliot Rodger? This is what he had to say in the novel length autobiography he distributed prior to his spree: “All those popular kids who live such lives of hedonistic pleasure while I’ve had to rot in loneliness all these years. They all looked down upon me every time I tried to join them. They’ve all treated me like a mouse ... If humanity will not give me a worthy place among them, then I will destroy them all. I am better than all of them. I am a god. Exacting my retribution is my way of proving my true worth to the world.” Acute or chronic social rejection has been found to be a major contributory factor in 87 percent of all school shootings between 1995 and 2003.

But there’s one final factor that ties together this triumvirate of destroyers. Not only did Rodger, Kemper, and Kaczynski experience severe humiliation, they also had an immense psychological height from which to fall. All were intelligent—Kemper had an IQ of 145, near genius level—and all were markedly grandiose, with Kaczynski hoping to spearhead a global revolution and Rodger’s autobiography greasy with entitlement and narcissism, including descriptions of himself as a “beautiful, magnificent gentleman.” Kemper gloried in his notoriety: during a long drive with police officers following his arrest he paraded himself at rest stops, showing his handcuffs, and speculated excitedly about press coverage. It’s even been suggested his confessions of cannibalism and necrophilia were status seeking untruths. All three had a need for status that was unusually, perhaps pathologically fierce, and so the humiliations they suffered would’ve been all the more agonising. Writes mental health expert Professor Marit Svindseth, “even the slightest disagreement or slur from a person of similar or higher status rank might be enough to humiliate the narcissist.” Feeling entitled to a place at the top of the game, they were driven to depravity by life at the bottom.

This pattern—male, grandiose, humiliated—is also evident in those who commit nonviolent acts of destruction against their game. From an early age Robert Hanssen dreamed of being a spy. He loved James Bond and bought himself a Walther PPK pistol, a shortwave radio, and even opened a Swiss bank account. But Hanssen’s father was abusive, belittling him and inflicting strange punishments. “He forced him to sit with his legs spread in some fashion,” his psychiatrist reported. “He was forced to sit in that position and it was humiliating.” Such degradings also happened outside the home. Whenever his best friend’s mother encountered his father, there was “always something belittling about Bob. No matter what Bob did, it wasn’t right. I’ve never seen a father like that. He would never have a kind word to say about his only child.” Even after Hanssen was grown and married, the degrading continued. When his parents came round for dinner, he’d be too frightened to come downstairs. “He would get sick to his stomach and could not face his father at the table. [His wife] Bonnie finally said, ‘If you are under this roof, if you cannot be respectful to Bob, then you are not welcome to come.’”

But Hanssen’s need for status was strong. He became an “ultra-religious, devout, zealous” member of the Catholic Church, a part of the elite group Opus Dei that was the Pope’s personal prelature. He joined the FBI in 1976 where he hoped to live a life of statusful excitement as a counter intelligence operative but was repeatedly turned down for such prestigious roles. According to his biographer, he kept finding himself in back rooms, “watching from afar as others performed more exciting work.” Hanssen was seen as “very, very smart” with strong technical skills, but he came off as superior and difficult, carrying a “wry expression on his face. He just didn’t suffer fools gladly. Why should I have to reduce myself to this level?” In 1979 Hanssen contacted the Soviet Union and offered to spy for them. He wasn’t arrested until 2001, by which time he’d passed thousands of top secret documents to the KGB and compromised many American assets, some of whom were executed. Hanssen is considered the most damaging spy in US history. Following his trial his psychiatrist said, “If I had to pick one core psychological reason for his spying, I would target the experience he had in his relations with his father.”

Humiliation is also a principal cause of honour killings. They involve a family conspiring to murder someone they believe has brought humiliation upon their family by breaking the rules and symbols of their game, usually with behaviours related to sexuality or being “too Western.” In some Muslim, Hindu, and Sikh niches it’s felt the only way to restore the family’s lost status is to kill those perceived to be at fault. Victims might have refused arranged marriage, had premarital sex or an affair, or sought a divorce. They might’ve wanted to renounce their faith entirely. Some killings happen as a result of being a victim of rape or wearing jewellery. The victims are almost always women, sometimes gay men, and the perpetrators surprisingly gender diverse. One albeit small study of 31 killings across Europe and Asia, by Emerita Professor of Psychology Phyllis Chesler, found women were “hands on killers” in 39 percent of cases and co conspirators in 61 percent. The exception was India, where women were the killers in every case. Chesler writes that these families who kill are often viewed in their communities “as heroes.” Statistics vary, but the UN estimate of around five thousand such deaths a year is conservative.

One danger of surveying extreme cases is that us normals can feel exempt from their lessons. But in their looming shadows, thoughtful readers might detect their own silhouettes. Surveys hint at how gruesomely painful episodes of humiliation can be to ordinary people, and are suggestive of their ability to summon demons, with one finding 59 percent of men and 45 percent of women admitting to homicidal fantasies in revenge for them. Others might object entirely to attempts at understanding such reprehensible acts, as if doing so somehow permits them. The language of blame and forgiveness might be suitable for courts, churches, and those directly affected, but by allowing moral talk to arrest our thinking, we become less useful; less able to identify risks and preventatives.

In 2014, in the aftermath of Elliot Rodger’s killing of four men and two women and his injuring of fourteen others, people began looking for the cause of his barbarity. What demonic power could’ve derailed Rodger’s journey of life with such force? Commentators from Glenn Beck on the Right to Vice magazine on the Left soon identified his obsession with the computer game World of Warcraft. “Please listen to me, you’ve got to get the video games out of your child’s hand,” said Beck. “They cannot handle it. This is not the same as Pac-Man. These are virtual worlds where they live.” Similarly, Vice pointed to “the addictive cycle of gaming” that takes players “ever further away from nurturing human contact, love, and social ambition.” But there’s a problem with these stories, evident in Rodger’s 108,000 word autobiography.

My Twisted World: The Story of Elliot Rodger is an extraordinary document. Gripping and appalling, it recounts in bracing detail his descent from “blissful” early childhood to a young adulthood of rejection, hatred, and homicidal madness. His grandiose need for status is present from the start: we learn his father hails “from the prestigious Rodger family” whilst his mother was “friends with very important individuals from the film industry, including George Lucas and Steven Spielberg.” Life was essentially happy, aside from his parents' divorce, up until he realised he was becoming shorter and weaker than his classmates. “This vexed me no end.”

The ages between nine and 13 were Rodger’s “last period of contentment.” In his social life he began to notice “there were hierarchies, that some people were better than others ... At school, there were always the “cool kids” who seemed to be more admirable than everyone else.” He realised he “wasn’t cool at all. I had a dorky hair style. I wore plain and uncool clothing, and I was shy and unpopular ... on top of this was the feeling that I was different because I am of mixed race.” Following this realisation, nothing would be the same. “The peaceful and innocent environment of childhood where everyone had an equal footing was all over. The time of fair play was at its end.”

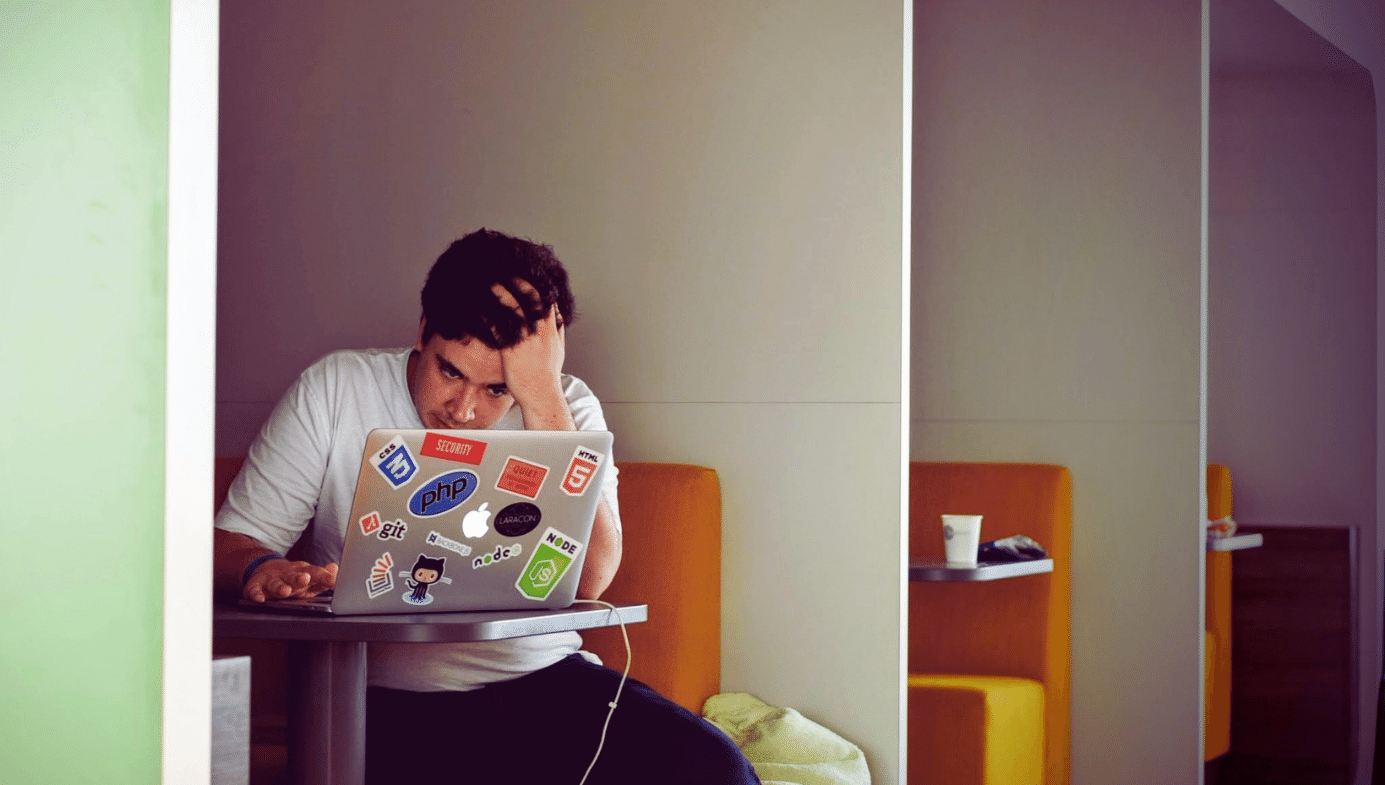

As a boy, he’d practised being “cool” by learning to skateboard. Now he was older, the rules had changed: “The ‘cool’ thing to do now was to be popular with girls. How in the blazes was I going to do that?” Rodger found himself shunned and bullied. “I was extremely unpopular, widely disliked and viewed as the weirdest kid.” But he found succour in the online computer games he’d meet with others to play, sometimes hanging out at an internet cafe until 3am: “I was having so much fun outside of school with my friends at Planet Cyber that I didn’t really care about getting popular or getting attention from girls.” When he discovered World of Warcraft, a game that allows players to team up online and pursue missions, “it really blew my mind. My first experience with WoW was like stepping into another world of excitement and adventure ... it was like living another life.” It became an obsession. “I hid myself away in the online World of Warcraft, a place where I felt comfortable and secure.”

Meanwhile the budding of his sex drive was proving hellish. Terrified of females and yet desirous of their approval, Rodger’s teenage years were spent in rejected, dumbfounded agony. He begged his parents not to send him to a mixed gender school. His peers mocked him, threw food at him and stole his belongings. He spent every possible moment in World of Warcraft, achieving the extraordinary status of its highest level, a “huge and important accomplishment.” The three local boys with whom he’d play online were “the closest thing I had to a group of friends.” But then Rodger made a grievous discovery. Those friends would often meet up in secret so they could play without him. “Even in World of Warcraft, I was an outcast, alone and unwanted.” He began to feel “lonely even while playing.” He’d break down in tears in the middle of games. “I began to ask myself what the point was in playing it.” So he stopped.

And then something switched. Up until this point, Rodger had presented as confused, miserable, and bitter. He was also hateful: his fear of women had curdled into a powerful misogyny, his loathing extending to the “cool” men they chose to date. But angry misogynists, sadly, aren’t rare. Only when his source of connection and status was lost did absolute pandemonium let loose in his thoughts. “I began to have fantasies of becoming very powerful and stopping everyone from having sex,” he wrote. “This was a major turning point.” On his final day of playing World of Warcraft, he described to his last remaining friend his “newfound views” that “sex must be abolished.”

Rodger’s brain had taken his feelings of debasement and resentment and magicked them into a story in which he was the hero. It said his suffering was the fault of women, who “represent everything that is unfair with this world” and who “control which men get [sex] and which men don’t.” By always choosing “the stupid, degenerate, obnoxious men,” they were going to “hinder the advancement of the human race.” He dreamed up an “ultimate and perfect ideology of how a fair and pure world would work.” Sex would be outlawed. Women would be destroyed, with some remaining to procreate via artificial insemination. He took these hideous visions to be evidence of his superiority. “I see the world differently than anyone else. Because of all the injustices I went through and the worldview I developed because of them, I must be destined for greatness.” In the brain spun dream in which he’d become lost, his misogyny was righteous. “All I ever wanted was to love women, and in turn to be loved by them back. Their behaviour towards me has only earned my hatred, and rightfully so! I am the true victim in all of this. I am the good guy.”

Rodger was 17. For the next five years until his killing spree, besides sporadic returns, his online game playing ceased. At the same time, his misery, loathing, and madness caught fire. World of Warcraft had been the only place he’d felt of value. It was a status game and one he’d excelled at. Far from being the cause of his madness, it was more likely the last thing keeping him sane.

Excerpted from The Status Game: On Social Position and How We Use It by Will Storr, published by William Collins. Copyright © 2021 by Will Storr.