Politics

The Good Death—Cancel Culture and the Logic of Torture

It is unsettling to consider how similar today’s public cancellations are to those public executions.

Cancellation is a public execution, during which a person is pilloried and destroyed. But while we have become used to the cycle of manufactured outrage that preludes every cancellation, the desperate public apologies, and the devastating consequences for the people whose lives are ruined, we are often at a loss to know what we could do to stop this type of serial assault. Part of the solution is to gain as clear an understanding of the phenomenon as possible by probing its structure. Philosophical and historical scholarship on public executions and torture can help to illuminate the moral logic that drives the cycle of abuse. For both public shaming and cancellation are structured like public acts of torture, and their aims are disturbingly similar means of enforcing political or cultural conformity.

A public execution

In The Spectacle of Suffering, a wide-ranging study of public executions in preindustrial Europe, Pieter Spierenburg points out that “execution originally meant the carrying out of any sentence, not only death sentences.” What emerges from Spierenburg’s discussion is that public executions were to some extent scripted and required the convicted or condemned to play a part. This was connected to the exemplary function of the execution as a deterrent: “The edifying aspect then lies in a punishment suffered humbly and dutifully. All this of course presupposes a society which tolerates the open infliction of pain. Only then can the authorities hope that the example will be effective.”

It is unsettling to consider how similar today’s public cancellations are to those public executions. Of the three elements listed by Spierenburg, the complicity of the condemned is the most fascinating. As Spierenburg argues, “In the eyes of the authorities the staging of executions achieved its most beautiful form of ultimate success” when the criminal repented and embraced his punishment. “For this his co-operation was required. He had to be convinced of the righteousness of his punishment … Notably those who were going to die were expected to be penitent and convinced of the wrongness of their own acts and the righteousness of their death.” The absence of such co-operation not only made the execution less perfect, but it also rendered it potentially counter-productive: a condemned man who refused to play the role of penitent might engage the sympathy of the public, especially if there were doubts surrounding their alleged guilt, and the whole spectacle might then turn against the executioners and the authorities, and trigger riots, as sometimes happened.

In our current climate of cancellation, the submissive assumption of guilt is performed through the humiliation of the public apology. This is not a coincidence: an apology functions like a confession—it implies acknowledgement of wrongdoing. Even (and especially) if the shamed or cancelled person is innocent of any wrongdoing, the apology is the sacrament that makes the accusation real after the fact. It is the seal that retrospectively authenticates the righteousness of the punitive process. It is the moment when the victim of the cancellation plays his part and willingly goes to his death. To apologize is to die the good death—the accused gives his persecutors the performance they want and need, and validates their worldview.

Yet the display of voluntary humiliation is not enough to make a good execution. The public spectacle of pain (which in cancellations is primarily the psychological pain of humiliation and ostracization), its toleration by society (indicated by the gleeful dissemination of the images of public humiliation), and the exemplary nature of the execution also play their part. To understand the full scope of the impact, we need to expand our frame of reference and approach cancellations as public executions of a very specific kind—they are a public form of torture. It is only when we look at cancellation as a form of torture that the full force of its violence becomes apparent.

Destroying the body

In The Body in Pain, an investigation of pain as a destructive force in human experience, Elaine Scarry argues that “torture consists of a primary physical act, the infliction of pain, and a primary verbal act, the interrogation. The first rarely occurs without the second.” This means that in torture, pain is typically inflicted with the aim of extorting information from the victim, who is made to say things he does not want to say, whether it is a confession of guilt or intelligence that the torturers wish to obtain. On the one hand, the physical body is made to suffer. But torture also attacks the mind. Because thoughts cannot be grasped or put to the rack, physical pain is used to coerce the spirit of the victim. The body is the means to get to the soul.

Torture takes aim at the physical body because the flesh mediates the mind’s contact with the world. In normal life, we tend to rely on surrounding objects and environments almost as if they were extensions of our body. “Humans and their world,” writes Scarry in Resisting Representation, “are coextensive.” Chairs relieve some of the supporting work of our spine and legs. Bicycles and cars are extensions of our legs and feet, which cannot move that fast on their own. Houses and clothes envelop us like extra layers of skin, protecting us from the elements. This prosthetic-like feature of our immediate surroundings is especially noticeable in people with a disability. A wheelchair or crutches or a hearing aid replace the functions of certain body parts. But even for able-bodied people, the world as it is immediately present to us is rarely experienced as completely external.

Part of the aim of physical torture is to make this surrounding world alien and hostile. Victims of torture are typically deprived of basic comfort. They must sleep on dirty floors or on dirty mattresses. They are given spoiled food to eat or dirty water to drink, which causes them to be sick. During interrogation, their chair is kicked out from under them. In this way, elements of the world that are usually familiar, intimate, and comforting are made unreliable and hostile. This has the effect of reducing the victim’s world to their own physical body. The longer and the more extensively this process is sustained, the more the torture victim will find their world shrinking.

But the infliction of physical pain also alienates the victim from their own body, which is equally turned into an enemy. As Scarry puts it, “The prisoner’s body [is made into] an active agent, an actual cause of his pain.” To inflict pain is to make the body hurt itself because pain is always situated upon or inside one’s body. But while one might potentially or theoretically run away from an external agent of pain or discomfort, the pain inflicted by one’s own body is inescapable. This pain need not even be severe to be engulfing. Just consider the extent to which a sore tooth can compromise one’s functioning. A headache can be debilitating. As the pain inflicted by one’s own body increases, so, too, does the sense of being engulfed by it.

Of course, instances of public shaming or cancellation do not involve the infliction of physical pain—the physical body of the victim is not destroyed (although some shaming and cancellation certainly includes the threat of physical violence). Nevertheless, a very similar effect is obtained by destroying the victim’s social world. This explains why it is important for shaming and cancellation to be public events—they are meant to isolate the accused from the community. This isolation is experienced as physical as much as spiritual. The destruction of the world that is achieved in torture by the destruction of the body and its relationship to its immediate physical surroundings is achieved in cancel culture by the infliction of an abject state of loneliness, which equally cuts the victim off from the world.

This experience has been most eloquently described by Hannah Arendt in her analysis of The Origins of Totalitarianism. Arendt argues that inducing a state of loneliness in people has the effect of destroying all sense of community, reducing individuals to isolated atoms, and thereby preparing them, through abject fear, for totalitarian rule. As Arendt explains, “Totalitarian domination … bases itself on loneliness, on the experience of not belonging to the world at all, which is among the most radical and desperate experiences of man.” As Arendt points out, “Loneliness is not solitude. Solitude requires being alone whereas loneliness shows itself most sharply in company with others.” A lonely man “finds himself surrounded by others with whom he cannot establish contact or to whose hostility he is exposed … In solitude, in other words, I am 'by myself,' … whereas in loneliness I am actually one, deserted by all others.” Solitude can be enjoyed—it is often even a luxury—whereas loneliness is terror.

The function of public shaming and cancellation is to inflict loneliness—it cuts the victim off from the family of man. It makes him an abject untouchable and has as its only aim his total removal from society. This is achieved by publicizing the cancellation, which ensures that this person will lose his job, his livelihood, his social circle, and will almost certainly not find another job in the foreseeable future. In close analogy to physical torture, where everyday objects (a chair, the food one eats) and even the body itself are turned into hostile weapons, the shared world is turned into a hostile environment for the publicly shamed person, who is now shunned by everyone. The very people who were only recently friends and colleagues are now the weapons that inflict pain through their absence, confirming the victim’s isolation.

In this way, the security a person feels within the human community is destroyed and the world is made hostile. It effectively reduces the limits of one’s being to the limits of the body. Any person who has ever suffered severe public shame will acknowledge that the limits of one’s body are a thin shell between oneself and a hostile environment.

Destroying the voice

The destruction of the body of the torture victim typically entails the destruction of their voice, which is the second act of destruction Scarry identifies in her analysis of torture. As Scarry explains, the voice of the torture victim is present in screams of pain and in coerced speech. In torture, the victim’s screams are “made the property of the torturers in one of two ways. They will, first of all, be used as the occasion for … another act of punishment. As the torturer displays his control of the other’s voice by first inducing screams, he now displays that same control by stopping them: a pillow or a pistol or an iron ball or a soiled rag or a paper packet of excrement is shoved into the person’s mouth … Secondly, in many countries these screams are, like the words of the confession, tape-recorded and then played where they can be heard by fellow prisoners, close friends, and relatives.”

Like torture, public shaming and cancellation also appropriate the voice of their victim. Once accused, the victim has no verbal recourse. Any denial of the charge is perceived as further evidence of intransigence—all protest becomes a case of protesting too much. Only confession and contrition will do. Here, the victim’s voice, and their very words, are used against them as weapons. To speak at all is to be guilty, unless one agrees to speak as a ventriloquist’s dummy, proclaiming the confession that one’s torturers (or one’s employer, eager to please the mob) have drafted.

This is why, in cases of cancellation, it is not the initial accusation or calling-out but the apology (which amounts to an admission of moral guilt) that is lethal. By apologizing to your tormentors, you surrender your voice and indicate that you will not bite the hand that throttles you. You have become docile. Furthermore, the public spectacle of humiliation and confession demonstrates to one’s allies, close friends, and relatives what is in store for them should they incur the mob’s wrath. Like the recorded screams of the tortured mentioned by Scarry or the public executions mentioned by Spierenburg, this is the violence of intimidation by example.

There is a bitter but valuable lesson here for those who face public shaming or cancellation. Whatever you do, and however tempting it may be, you should never, ever apologize. The only sensible response is defiance. This takes courage, and it may seem painful and torturous, but the situation is already painful and torturous, and apologies are unlikely to change that. The victim can at least reclaim or maintain some self-worth by biting back.

Of course, it makes perfect sense to apologize if you have committed an actual crime or offence. But in that case, a sincere apology almost always has restorative force. It will help a perpetrator to come to terms with what they have done and begin to make amends. And for the victims and their families, even if they cannot (yet) bring themselves to forgive, a sincere apology at least entails an acknowledgement of wrongdoing and relieves them of the burden of having to insist that a wrong was done. It ends a fight for recognition and allows a healing process to begin.

But in cases of shaming and cancellation, the apology never makes any difference at all: it is simply part of the punishment. Where restorative justice sees apologies as part of a constructive process towards rehabilitation, mobs use apologies as an instrument with which to inflict more pain. There is absolutely no sense of reciprocity, forgiveness, or closure.

Cancellation and shaming are insidious because they rob their victims of their proper voice. To have one’s voice stolen in this way is a deeply traumatizing experience: it makes clear that nothing one says, not even speaking the obvious truth, will make any difference at all. This is perhaps the moment when the sense of loneliness is most profound and the victim feels most desperately lost.

Destroying truth

A significant consequence of these torture tactics is their contribution to the destruction of truth, which is part and parcel of the destruction of the social world, and which is to a considerable extent achieved by robbing victims of their voice. One of the reasons shamed victims are coerced into false or self-incriminating speech is that the mob needs to maintain a view of reality that is impervious to empirical testing. Reality and truth are decreed by ideology rather than established through the conventions of empirical research and a rational exchange of views. This is nowhere clearer than in debates about race (where the new-fangled and luridly racist concepts of “white supremacy” and “structural racism” trump all empirical evidence about the true and complex causes of racial inequality) and gender (where the concept of gender has swallowed up biological sex to the extent that even sexual dimorphism in humans is now dismissed as a mere social construct rather than a basic empirical fact).

This process has been successful at universities, where even tenured professors are now sufficiently scared of saying anything that might offend, even if it is established science or demonstrable fact. But when the voices of science and reason are silenced, totalitarian rule is in the ascendant. As Arendt explains, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.” Even those who privately know that they are professing ideological untruths also know that they ought not to say so out of fear for their livelihoods. It is not even clear anymore whom amongst one’s colleagues and friends one can trust. The new truths are centrally dictated and the options are: conform or perish.

This is the human condition in a world of absolute relativity of facts and values (except its own, of course). It is a world in which nothing is certain (except the diktats of the mob), and where anything is possible (except the commonsensical and the empirically testable). It is a world in which lonely people (teachers, students, writers, and basically anyone who is terrified of the consequences of dissent or perceived “insensitivity”) are made to live in an alternative reality where there is no more recourse to facts. It is a world governed by the only thing that remains when objective truth falls away: power.

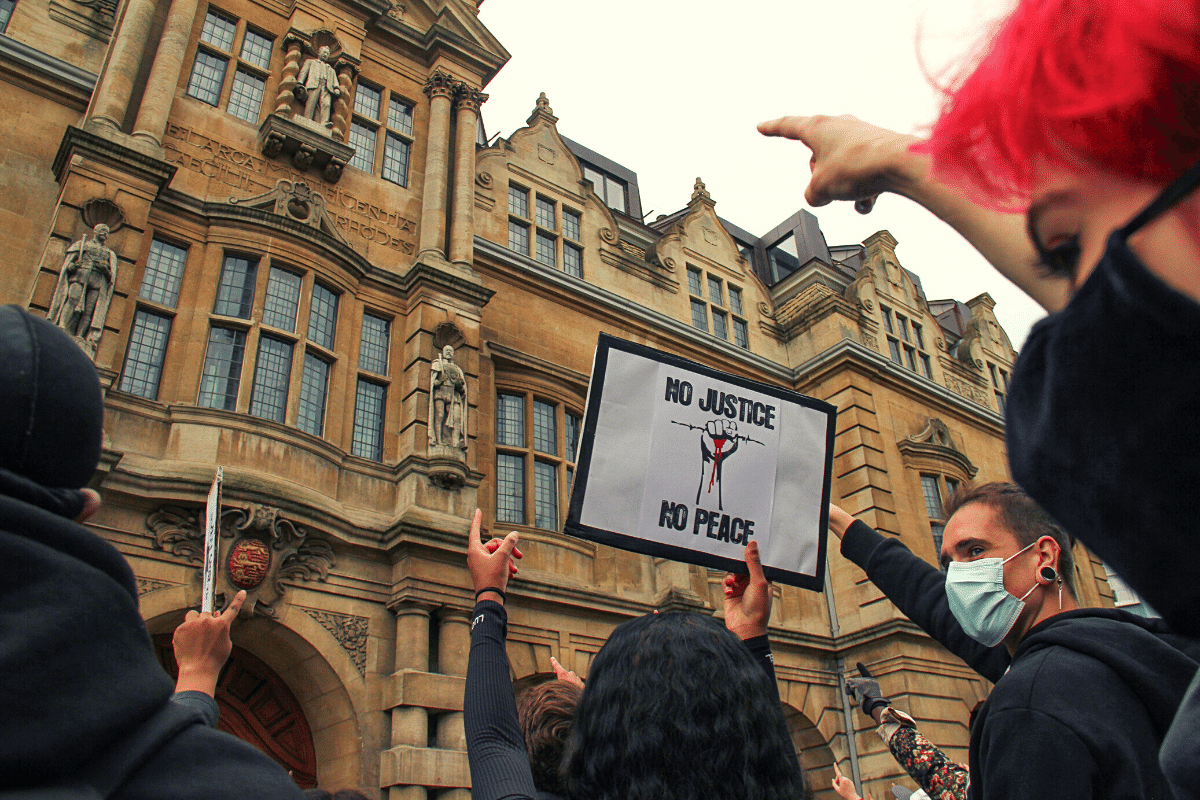

The loneliness induced by the spectacle of public shaming and cancellation is central to establishing this ideologically determined universe. “What prepares men for totalitarian domination in the non-totalitarian world,” writes Arendt, “is the fact that loneliness, once a borderline experience usually suffered in certain marginal social conditions like old age, has become an everyday experience.” The spectacle of shaming is meant to strike fear in the hearts of the public and induce it to conform rather than say aloud what we know to be true. Like the bodies broken on the wheel or dangling from the gallows in preindustrial times, the faces and names of the shamed on social media are exposed as deterrents. This is what happens if you disobey, and it could happen to anyone at any time.

Destroying society

And it does. Many commentators have noted the apparently arbitrary selection of victims for cancellation and shaming. Why person X and not person Y? This, too, is a feature of the totalitarian moral logic at play. Like Kafka’s K, we all might wake up one morning and find that we have been accused without having done anything wrong. But when the victims are arbitrarily selected, loneliness becomes an everyday experience because we soon learn that we must be extremely careful about anything we say or do. We become each other’s gaolers even while we inflict the most stringent surveillance upon our own thoughts and speech. The walls have ears, and the social world is hostile. In this sense, arbitrariness is central to the tactic of destroying the social world. Everyone is a suspect and therefore a potential victim. Anyone could destroy anyone at any time with a tweet. Trust no one.

At the same time, however, the claim that cancel victims are arbitrarily selected is only partially true. There does seem to be a profile, or a set of profiles. Many victims of cancel culture were not known to the public at large before their public falls from grace. Their shame made them infamous. Furthermore, many victims have been well-meaning liberals who are targeted for what is often a very minor or insignificant pseudo-transgression: a joke that was ill-judged, a hasty tweet that turned out to be an unintended embarrassment, or the use of an innocuous word that only extremely sensitive people might construe as racist or sexist. In fact, many victims of cancellation have not done anything wrong at all.

Cancellation is a cowardly tactic. It is a form of mob justice that likes to prey on easy victims. In this respect, it again follows the structure of torture, which is equally cowardly. The power differential in torture is absolute. Torturers do not risk anything by inflicting torture. They run no risk of retaliation because the victim is helpless. The victims of cancellation and public shaming are similarly selected for their vulnerability. One reason why so few openly racist or sexist persons are ever shamed successfully by progressive mobs is because such people are simply not intimidated by their accusers and usually inhabit social circles beyond their reach. Confirmed white supremacists or Stalinists, for example, already tend to exist on the fringes of society and are hardly embraced by mainstream culture. Their convictions are so strong that, in a sense, they have been happy to cancel themselves and wall themselves up in the fortress of their own ideological bubble.

Mobs therefore select their victims carefully from the ranks of the impressionable—liberal-minded people who are already committed to progressive values, who are terrified of being called racist or sexist, and whose sense of identity to a considerable extent relies on their allegiance to inclusive and tolerant values. But these are the people least likely to be guilty of the moral crimes of which they stand accused. And this in turn explains why they so often have the perfectly understandable but wrong reflex of trying to apologize for any perceived wrongdoing. Even their moral goodness is cynically turned into a weapon of destruction. Being kind becomes painful.

Inscriptions of power

This brings us to the concluding part of the torture cycle: the inscription of the torturer’s truth onto the bodies of their victims. Such inscription is necessary because any truth, to manifest itself, must be inscribed somewhere. This is something that Scarry explains in her discussion of warfare. Wars are ideological contests: two worldviews compete for dominance of the social world and only one can win. This means that, for the duration of the conflict, it is unclear which set of rules and values obtain. Once the conflict has been decided, the winning side needs to reconnect its rules and values to “the force and power of the material world” to establish them as the new reality. Wounded bodies are, in a material sense, undeniable proof of victory, and consequently proof of the reality of the worldview that emerged triumphant.

It is no different in the culture wars. The shamed faces of humiliated cancel victims are ideological truth made manifest. In its ability to inscribe its morals into one’s flesh and soul (one’s social body and one’s voice, both cancelled and appropriated) the mob manifests the reality of its power. Social power is only real to the extent that it can make itself real in its consequences. If you can make others act in the way you want them to act, your power over them is real. You can establish this power either by making people believe that you are right (which is why all totalitarian systems seek to control education, which allows them to indoctrinate the next generation), or through the blunt force of violence and intimidation. But either way, as the Greek-German philosopher Panagiotis Kondylis has argued, he who can dictate binding interpretations of the world will rule the world.

When we act as if the mob is right, if we unconditionally affirm their description of the world, their description becomes real in its consequences. How could you deny its reality if you yourself act according to its principles? If you act as if your oppressor is righteous, you become complicit in your own bondage and effectively prove, through your own actions, that your oppressor is righteous. At which point, you die the good death. This is also why, as Susanne K. Langer wrote in Philosophy in a New Key, “Men fight passionately against being forced to do lip-service, because the enactment of a rite is always, in some measure, assent to its meaning … It is a breach of personality. To be obliged to confess, teach, or acclaim falsehood is always felt as an insult exceeding even ridicule and abuse.”

This, again, is why it is the apology that kills: it is an act of moral self-inscription and, thereby, self-debasement. Like the good convict sticking to the script in a preindustrial execution, the performance of confession and remorse gives those in power what they want and need most: acquiescence. After that, the victim disappears from the social world, used up and discarded while the mob moves on to its next victim. The ideological beast is like Mammon: it continually needs to be fed to sustain itself. And so, one soul at a time, we are to be turned into the armies of the undead.

The execution has been cancelled

Ideology is callously wasteful of human life. While insistently claiming the safest of safe spaces for their own allies, activists are happy to make life a living hell for everybody else. For people who claim to be supremely concerned about harm, mental health, and the dignity and fragility of humans, they are unsettlingly eager to destroy casually and even gleefully those with whom they do not agree. In doing so, they happily ignore the inconvenient fact that the cancelled and the shamed are also human beings with real lives, real feelings, and real families, who, like the rest of us, only have one shot at life and happiness before disappearing into the eternity of non-existence. What God-like hubris to assume for oneself the right, on the most specious of moral grounds, to cut such lives short.

It is difficult to know how to stop this relentless onslaught of destructive rage. The mob is shapeless and faceless. Although it is spurred on by prominent spokespersons and cheerleading theorists, there is no central agency or group of agitators, let alone a designated leader or official institution, whom one could address as the prime movers or responsible parties for any specific instance of public shame or cancellation. The mob provides perfect cover for individual responsibility, which is another badge of cowardice. Yet the analysis of cancellation and public shaming as a form of public torture does provide at least three suggestions that might help disrupt its destructive force. These three suggestions are not new or original, but they are potentially powerful and therefore useful as forms of resistance.

Since public executions rely on the presence and support of an audience to be successful, a first way of resisting the lethal cultural logic of torture would be to refuse it an audience. Ignore cancellation or make a very public spectacle of your disdain for the process. There is an important role to play here for employers and administrations: do not give in to moral blackmail. Do not fire, silence, or remove colleagues or employees who have been shamed or cancelled for alleged moral offences. Resume business as usual as if nothing has happened. Do not allow the cancellation to be an issue. Ignore calls to boycott stores exposed to shame, continue to attend performances by artists who have been called out, read books considered toxic, socialize with colleagues who have been marked out as falling short of the latest moral standard. Opposition must be public for it to matter. It pays to make a spectacle of one’s dissent.

Since the participation of the victim is crucial to a good execution, we must also, as individuals, resist shame if we become the target of a mob. This is the most difficult form of resistance, as it typically requires tremendous courage. We should therefore not blame victims if they cannot muster the courage to stand up to their persecutors, for that would simply increase their sense of shame and loneliness in a heartless and unspeakably cruel manner. And yet rejecting shame and guilt is central to defeating the psychological torture practices of the cancellation mob. Do not follow the script. Most certainly never apologize. Do not engage: if the mob were susceptible to rational argument or common decency, they would not resort to torture practices in the first place. Remember that those who torture you have no reasonable grounds for appealing to either your kindness or your politeness: that privilege they forfeited when they set about destroying you for sport. Be defiant. Refuse to die the good death. Bullies tend to move on from victims who do not play by their rules.

Finally, we must all publicly speak up against mobbing. The key to breaking the stranglehold of ideological conformity is to keep dissenting speech alive. Raise your voice, for public speech is the power that allows one to break the bonds of loneliness. It tells others, and the victims of cancellation specifically, that they are not alone. Do not allow your colleague or your student or your friend to be the only oppositional or dissenting voice in the room. It is important to declare allegiance, even if only to make clear that you agree to disagree rather than to silence. Stand by people with whom you disagree to show that dissent is the essence of freedom and pluralism. You must show that, whatever threats are issued, the oppressor does not own your mind. And if many demonstrate that the oppressors do not own their minds, the oppressors will soon find they own nothing. In this way, and in this way only, can we oppose tyranny as a community rather than as desperately isolated individuals.

The isolated voice of dissent is easily dismissed as the cry of the insalubrious mind. But if we are to be free, if we are to deserve and earn our freedom (which, as history shows, is never a birth-right but always embattled), we must join other voices that speak truth to power. This is really very simple logic: a single voice is lonely and abject. Two voices are a group. By acting in public, by performing the political act of standing up and speaking for the common good, people can bring about change. For this reason, courage is the highest political virtue. For speaking truth to power doubtless entails grave dangers. But its potential rewards are immense. It may indeed be, as Arendt suggested in The Human Condition, “the miracle that saves the world.”