History

The Philologist, the Iraqi Girl, and Me

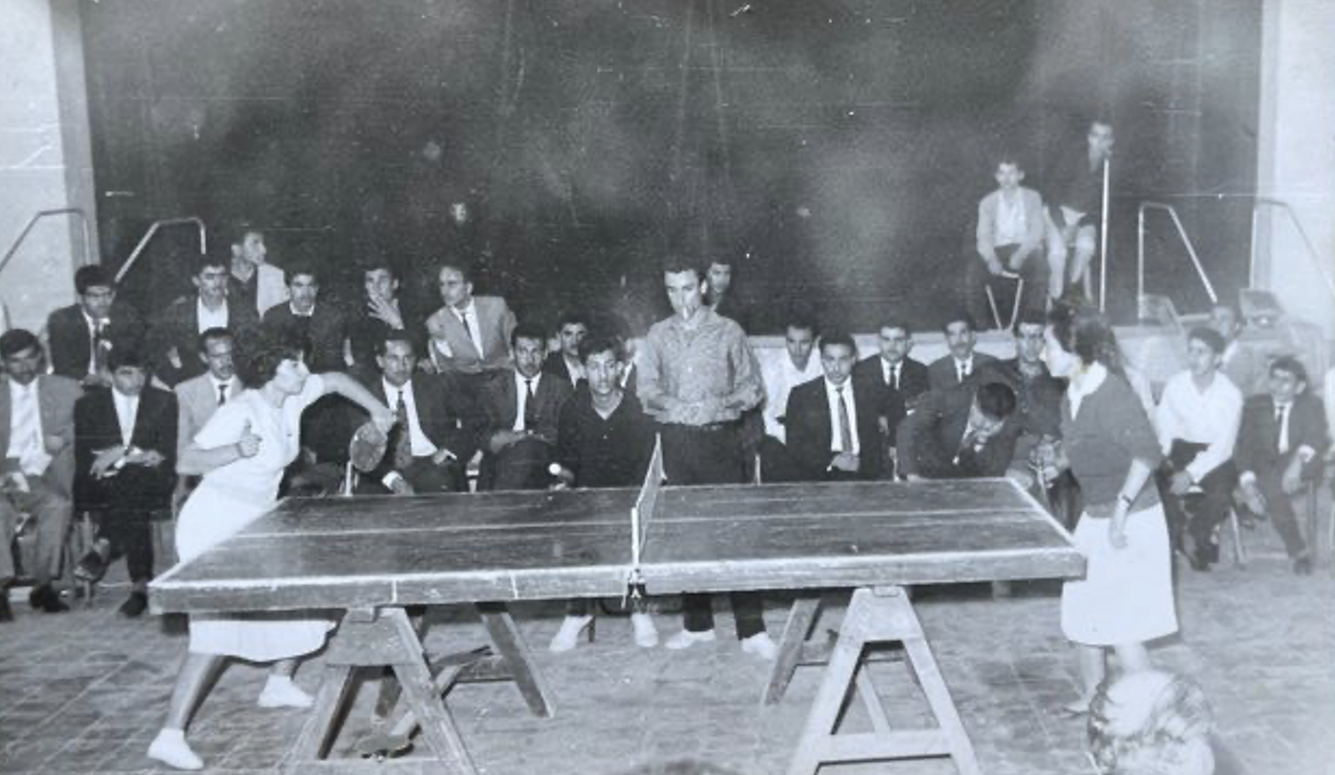

The comrades worked together, ate together, read together, showered together, used the latrine together, sang together to the sound of accordions late into the night.

I hadn’t bargained on the climate, especially not in the summer and especially not on the coast. That didn’t stop me from going ahead and doing what every self-respecting American college kid visiting Israel, such as Bernie Sanders, did back then—a stint of physical labor on a kibbutz.

We’re speaking of June 1962. Eichmann’s ashes had just been dumped in the Mediterranean. Aware of this but not of a lot of other things, sporting horn-rimmed glasses, khakis, loafers, and button-down shirt, I washed ashore at a left-wing settlement halfway between Haifa and Tel Aviv where the comrades worked at their own tile factory, in a banana plantation, and on the trawlers of quite an unpretentious little fishing fleet.

Of course, I knew from reading that kibbutzim were socialist successes. But as I got up at the crack of that first dawn to ride a manure-spreader out to the bananas I had no idea that various parties and sects of Zionist socialists bickered over who was the most successful at making the vision come true, over what keeping the faith entailed, over whether Joseph Stalin, in spite of everything, had been on the side of the angels, and most of all over whether babies and children should sleep in a dorm or at home with their parents. I knew nothing of any of this, nor, in my time on the kibbutz, would I have the strength to care.

Very soon I was scratching mosquito bites until they bled. Savage blisters flowered on my soft hands, and I drooped from harvesting bananas from dawn to early afternoon. This wouldn’t have been so bad if the kibbutznikim had been welcoming. But most ignored me, and those who didn’t hazed me. To be a lone volunteer on that kibbutz was to know again some of the joys of being a new boy at prep school, a Jew among WASPs. Here, as there, the old boys radiated self-confidence. And the self-confidence of these Hebrew-speaking farmers and fishermen, like that of the WASPs, seemed theirs exclusively—a state of grace no outsider or latecomer could achieve.

Granted, these people were Jews, and I was a Jew. Yet their pride didn’t seem to be something I could hope to share. It was foreign to this college kid who wasn’t all that self-respecting, this American out to find himself. Dressed in sandals, shorts, faded shirts, and floppy caps, the kibbutznikim tacitly, convincingly believed themselves to be nobility; supermen. They were as obviously the creators and possessors of their country’s past and present, and the heirs to its future, as the button-down WASPs were of America’s past, present, and future. I was too young and tired, and I stayed too briefly in Israel that summer, to find out that, like the New England prep schools and the WASPs, the kibbutzim and kibbutznikim had their glory days behind them.

I was assigned to work in the banana plantation. This was the hardest physical labor I’d ever done—far harder than earning a few dollars mowing suburban lawns in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. Bananas, it turned out, grow in bunches much larger than those you find in the supermarket. Each bunch weighed something like 90 pounds. You cut them down with a machete and wrestled them onto a trailer in the wet heat as the flies and other insects frolicked over your face, your arms, your chest, your legs. From the stumps of the stalks a clear liquid seeped, which in contact with your skin turned as black and sticky as pitch.

By 6am, having worked a full hour, and the Middle Eastern sun just beginning to do what it does, I’d be ready to return to my cot. The work was boring and hellish. Where was the ecstasy I’d read about in the translated essays of A.D. Gordon, the Zionist mystic who preached and practiced redemption through manual labor in the ancient Jewish homeland? This work, far from uplifting and redeeming me, was torturing me. How I hated those stupid, evil, endless bananas! And at 6am there’d still be another eight hours of work ahead.

My distress was noticed by the foreman. “You are an American weakling,” I was informed in English in the man’s exacting German accent. This comrade, this straw boss, managed to supervise a team of harvesters, haze me, and cut his own quota of bananas, all at once. Talkative, he let it be known that he was the last Jew to win a degree in philology or anything else from Heidelberg in 1932, which, if true, would’ve made him at least 50 years old.

“American gangsters,” he said. “Chicago is ruled by gangsters, and the rest of America also.”

“Oh? How do you know?”

“This is well known.”

“Have you been there?”

“This is well known. Therefore, one does not have to have been there.”

Was this philologist putting me on, or what? Hacking with the machete, I decided he was serious, yet couldn’t call up the strength to argue with him. Besides, it was disorienting for a lad who’d donated his dollar to the Students’ Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to hear America attacked and want to leap to its defense. I wouldn’t have known how to do it. Here I was abroad in Zion, and this philologist-foreman, who without a doubt had led a very interesting life, was baiting me by dumping on the only country of which I was a citizen. This was confusing. I bit my tongue and let him go on until I heard him say one day, “You know, Jews are not permitted into university in America.”

“That isn’t so. I go to university. I’m on summer vacation from university now.”

“Which?”

“Harvard.”

“You are lying. Jews are not permitted into Harvard.”

Following which our Harvard boy disputed not a word the marvelous German said. I found some added strength by imagining that the banana stalks were this Jew’s neck, but for the most part I’d get through the nine hours on will-power alone. Maybe I hoped that after a brief initiation, two weeks say, my body would get accustomed and I’d know something of Gordon’s joy.

It wasn’t to be. The weeks passed, and though my hands grew callused, the sun only grew hotter. I’d drag myself up the stairs of the communal dining hall for lunch, pick at the flyblown cucumbers and white cheese served from trolleys by sweating female comrades who didn’t shave their legs or armpits, and return to drop like a stone on my cot. There I’d lie in my work-clothes, my aching arms and legs spotted with banana sap, debating with myself whether it was worth taking a shower, knowing that 10 minutes after showering I’d be effortlessly sweating and the flies would be at me again. Only the half-hour before sunset was insect-free, as the flies knocked off and the mosquitos waited to clock in. All this, plus a lack of Hebrew, almost blinded me to the interesting details of kibbutz life—almost, but not quite.

There were female comrades, but somehow no sexy young women. I remembered that at the end of Justine, the author, Lawrence Durrell, punishes his heroine by sending her to lose her beauty on a kibbutz. Also I noticed that everyone in the dining hall read his or her copy of the same newspaper, the logo of which I had just enough Hebrew to decipher—it was LaMerhav, that is, “The Region,” the daily of Achdut Ha’avodah, the Unity of Labor party. I managed a smile remembering an American ad—“In Philadelphia, everybody reads the Enquirer.” Well, here everybody read LaMerhav.

At least they did in public, and all of life seemed to be in public. The comrades worked together, ate together, read together, showered together, used the latrine together, sang together to the sound of accordions late into the night. Their children, to top it off, slept and were raised together from day one, in their big house, the kibbutz’s most nearly comfortable and spacious structure. They also threw tantrums and talked back less often, I was to learn, than their age-mates in the cities. But like their age-mates in Tel Aviv or divided Jerusalem, the kids seemed to take it for granted that the world existed for them. In that respect they were American—which isn’t to say that these New Jews with their milk teeth, these little princes and princesses singing their songs in unison and raising dust, weren’t already tougher than any American Jew would ever be unless he was a new Louis “Lepke” Buchalter.

For three hours late every afternoon, and for most of the day Saturday, parents could be with their children. They met under the shade trees beside the adults’ bungalows. To the American looking on from a distance and never invited to come closer or take part, nothing on this intense commune seemed more intense than these family reunions. As for the philologist and his wife, they seemed to have no children. I’d glance at the forearms of every adult comrade. The philologist’s were unmarked, but the philologist’s wife was tattooed with a set of blue numerals, the sevens crossed. Not a few others were also numbered. I’d glance as I sat beside them in the dining hall, and then, surreptitiously, at their eyes, fascinated, nauseated, ashamed of myself for having looked down on or presumed to judge this community or anybody belonging to it.

These Jewish eyes, I’d thought, were the hardest I’d ever seen. But now I wondered if they were hard, or if they’d just seen too much. What were my bites and blisters compared with the scars these sweating, unsmiling, intolerant people—these fellow Jews of mine—would carry to their graves? What right did I have to mutter to myself about any of them? Though young and worn out from the bananas, I understood that I should be trying my best to be merciful.

As it was, during the rest of my stay I mainly succeeded in swinging between a feeling of superiority and its opposite. It was obvious, I decided, that my sympathies were wider than those of any of these farmers, graduates of Heidelberg or not. On the other hand, I was obviously no match in toughness, staying-power, endurance. It was all very well to be capable of empathy, but I already suspected that without toughness, empathy can be fatal. I was, in some ways, precocious, and was an inferior Jew to these Jews who covered their heads only to protect themselves from the sun and who did nothing to observe the Sabbath except work four-and-a-half hours instead of nine.

The kibbutznikim went to their tractors and manure-spreaders at dawn, seven days a week, like Harvard boys heading to Radcliffe. What I’d read in Gordon really seemed to apply. I was impressed. I was bored. I was in pain. I was determined not to cut and run too soon—I didn’t want to give the philologist the satisfaction.

So, for the first 40 out of my total of 80 days in the resurrected Jewish state I’d sway and be jolted on the dusty track out to the bananas. The sun’s disc would just be peeking over the hills to the east. I’d lift my eyes, and grit my teeth, and I never gave much thought to what or who was up in those hills. They were there, all right, the hills were, but it was as if they weren’t—or as if they were uninhabited. It was as if the country were an island. Of course, if I twirled the dial of the old Phillips in the kibbutz cultural center when no one was there to object—the Voice of America was what I was looking for—one station after another would come on broadcasting gibberish and wailing in a language even stranger than Hebrew. The comrades never tuned in these stations, nor VOA or the BBC, sticking instead to the campfire songs and Verdi of Radio Israel.

There was, indeed, someone up in those hills. But the noise on the radio was almost all a visitor to Israel in 1962 might hear from and about the Arabs, either on this side of the armistice line—the so-called Green Line—or the other. Did I as much as lay eyes on an Arab that summer? Certainly not on the kibbutz. I must have seen some, however, in my 80 days—I visited Haifa, from where not all the Arabs had run away in 1948, and after all, there were big Arab Israeli villages, kept in line by military government, only a few minutes’ ride from the bananas.

Probably I saw Israeli Arabs, and took them for Jews from Morocco or Iraq. I got into the habit late every afternoon of walking out along the rocky shore beyond where the surf beat at a Roman ruin to buy the Jerusalem Post at a combination kiosk and falafel stand. Possibly the brown-skinned man with the mustache who saved me a copy of the paper and on whom I practiced my scant Hebrew wasn’t one of the Afro-Asian Jews, as I assumed, but an Arab citizen of the Jewish state.

It wasn’t entirely my fault that I was so out of it, for I’d come to visit Israel right in the middle of the quietest decade it had known so far. This was a time when people weren’t pricking up their ears at the hourly news bulletin. The 1956 war in the Sinai was history, the Six Day War was buried in the future. In the meantime, the Green Line was comparatively quiet. There was as yet no Palestine Liberation Organization. According to the Post, the various Arabs were busy fighting among themselves—in Yemen, for instance, where Nasser of Egypt would use poison gas—and granting Israel a respite which some people thought would last forever.

True, in the Post that summer I read three or four stories about Israeli soldiers or civilians who had been sniped at, either in Jerusalem or on the far side of the Sea of Galilee. But nothing came of these incidents—they were on the front page for a day, then gone. The Israel Defense Forces didn’t strike back. It was as if the brave, successful new state accepted this level of violence against it as normal, tolerable, and got on with the job, which was to get up early in the morning and build all day.

It was, by Israeli standards, peace indeed. There weren’t any weapons in sight on the kibbutz, no army patrols, and if guards were posted at night I either didn’t notice or forgot them soon after leaving—what I did remember was the damned accordion music going on half the night. It was as if, 10 miles from where I loaded bananas, worried my bites, and slept the fitful sleep of the dead, there weren’t minefields, and, on the other side, up in the hills, no towns and refugee camps jammed with unhappy Palestinians and policed by the Beduin troopers of young King Hussein’s Arab Legion. I didn’t understand or sense that all this was just a lull. It was as if history for my cousins, my people, whatever it had been in the past, had come to a pretty happy ending.

To read the Post—there was nothing else I could read—was to have this illusion fortified daily. It was a cross between Pravda and a normal paper—a mouthpiece for Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion’s party, that is, the Workers of the Land of Israel Party. It was the establishment and the government and ruled in tandem with the rabbis to the right of it and some of the ex-Stalinists to the left of it, plus just one Achdut Ha’avodah minister. The Post was upbeat, it gave its readers only the news it thought they should have, it was confident about things, and as far as I could see it had every reason to be.

Things were all right. The borders were quiet, people were in work, Romanian and Moroccan immigrants were sailing in, new towns and factories were going up, and both the Moroccan Jews and the Israeli Arabs were behaving themselves. No news was good news—most of the front page that summer was given over to faraway happenings, especially the troubles experienced by the French in Algeria. The Jews in their very own country produced only two decent scandals while I was battling the bananas—the Yosselle Schumacher affair and the Robert Soblen affair.

Yosselle was a child kidnapped from one Hasidic sect by another, who was smuggled out of the country to Brooklyn, located by the Mossad, and returned to Israel. Soblen was an American Jew convicted of spying for the Soviets, who jumped bail and arrived in Israel. The US asked for his extradition, Ben-Gurion and his justice minister acceded, and on the plane back Soblen slashed his wrists. There were only two such stories in an entire 80 days. A quiet time.

The picture on the front page of the Post was usually of an astronaut or cosmonaut, or of Golda Meir the foreign minister or Ben-Gurion himself greeting Idi Amin or some other African guest at the airport. Ben-Gurion’s speeches, wherever he delivered them, were reported nearly word for word. Menachem Begin, whose book on the pre-state underground I’d read as a teenager and who, if I wasn’t mistaken, was the leader of the largest opposition party, was unmentionable in the pages of the only paper I could read. The Arabs of Israel never came in for notice except in sketchy reports of their blood feuds and in-house crimes of passion.

The rate of violent crime among Jews was or seemed to be more or less zero. Granted, once I saw a story in the Post headed “DETAINED FOR HITTING SOCIAL WORKER” and another reporting “HAIFA MEAT SKINNER KILLS COLLEAGUE, TAKES OWN LIFE,” the background to which was the protection racket in the abattoirs, which the Post editorially deplored. But such items were infrequent and didn’t complicate my impression of the country, its people, or the state of its soul.

As for politics, whatever LaMerhav was publishing and the kibbutz comrades were reading there was no hint in the Post that Ben-Gurion, the George Washington of his country, was still obsessed by the Lavon Affair, the so-called esek bish—“rotten business” in Hebrew. This clueless American would learn of it only the following year when Ben-Gurion quit over it and the New York Times reported why. It had to do with a bungled scheme years before to pit the Americans against the Egyptians by bombing US cultural centers in Cairo and Alexandria, and Ben-Gurion wanted those responsible punished though the heavens fall. “BEN-GURION WELCOMED TO STOCKHOLM AS SWEDEN ENJOYS SUNNIEST DAY” ran the Post’s top headline one day.

The philologist gave me his unsolicited views on the Soblen affair which the Post did cover. This man, he said, should certainly not have been handed over to the Americans, but he, the philologist, certainly wasn’t surprised that Ben-Gurion had done it. There was a Law of Return on the books—any and all Jews had the right to come to Israel and remain. Ben-Gurion, however, was opportunistic, slippery, not a man of principle—he sucked up to the Americans, the Rockefeller brothers, the capitalists. The boy from the Ivy League hacked away. His left-wing straw boss had a sense of Jewish solidarity. Or did he?

One night in 1947, the Heidelberg grad recalled, three men showed up at the kibbutz gate. They were Irgun people, terrorists, Begin’s boys, and they said the British were on their heels. This, the philologist said, was right after the Irgun had answered the execution of three of its own by kidnapping two British sergeants, hanging them in an orange grove and booby-trapping their bodies. The British were turning Palestine upside-down, a state of siege was in force, and now the fugitives showed up and asked to be hidden. Opinions were divided. A general meeting was called. Some comrades were for handing over the fascists on the spot. Others said that Jews shouldn’t turn Jews over to goyim. A vote was taken. The men, by a narrow majority, were allowed to stay the night.

A fishy story. The monolingual American remembered the hanging of the sergeants from Begin’s thrilling, self-righteous book, The Revolt, but he didn’t remember any such twist. And how, I asked the philologist, had he voted? “To hand them over immediately.” I didn’t necessarily believe the story, but I could believe that in such a situation the talkative Teuton could’ve done what he said he did, and heaving another load of bananas onto the trailer I decided that if Begin was disliked so much by him, the leader of the opposition couldn’t be all bad.

And so I permitted myself to leave the kibbutz after 40 days. My tormentor waved goodbye, confirmed in the knowledge that Americans are sissies, but I didn’t mind—I hadn’t signed on for life and I had to have a look at the rest of the country and its people, including its young women. It turned out that this kibbutz wasn’t a microcosm of Israel.

There were, to be sure, men and women in the streets of Haifa, Tel Aviv, and Jerusalem with tattooed forearms. But they weren’t such a big proportion of the population. The sun drummed down, and the flies and mosquitos buzzed and bit elsewhere too, but in the cities, and along the two-lane highways connecting them, there were consolations. The most encouraging thing was that people in the Jewish state could take notice of you and actually be friendly. They not only could work, and brag, but joke, laugh, and make a fellow Jew—even one from America—feel not unwelcome.

Were they angling for a handout? I saw that half the buildings, trees, and water coolers in the country were there thanks to the generosity of married couples from Great Neck. Did I look like a philanthropist? Not much. Yet strangers were ready to put themselves out to help this kid who spoke neither Hebrew nor Yiddish. They didn’t do it because I was someone special or privileged, I thought. They did it because, as it seemed to me, all of society here formed one all-embracing family, a network of mutual assistance and obligation. Anyone—even a Jew passing through on summer vacation—was apt to be treated with instant familiarity and could count on friendly help whenever he asked for it and also when he didn’t.

The rudeness and nosiness were hard to get used to. People jumped queues, told each other off, smoked under No Smoking signs, asked personal questions in megaphone voices. Everyone called everyone by his or her first name, and often by a nickname, a diminutive. Yet the familiarity saturating the air seemed to betoken respect and concern rather more than contempt. Here, if democracy was your pleasure, and if democracy consists of democratic manners, respect for your fellow citizens, modest possessions for all, luxury for none, and a sense of a common destiny, then this was democracy for you. If those were the hallmarks, Israel was more democratic than the USA. That was admirable, wasn’t it?

Here was a good society, where front doors need not be locked. A country without TV—a novelty, a delicious novelty for a young American snob. Here were bus drivers who took home as much, if not more, than professors—and neither muscle-workers nor brain-workers took home much. Here were men who collected the garbage, and tarred the roads, bantering and laughing all the way, shouting at each other and at me in Yiddish. Here were bookstores peddling the flotsam and jetsam and jewels of European culture, the remnants of libraries washed up on the rim of Asia, the shores of the Land of Israel.

Also here were people working hard for the common good who seemed to like it. Here were men and women, grocers and clerks and housewives, who looked out for one another. Here were Jews, especially young Jews born in the country and never out of it, who were square, all right, who drank soda pop and listened to Elvis when they wanted to anger their parents, but were easier in their skins than I was or any Jews known to me in the States were. Here was energy and optimism, solidarity and success, confidence and competence and toughness. They were individually and collectively winners, these Israeli cousins of mine.

Traveling up and down the country in buses and on the train, I no longer felt superior and/or inferior, and began to draw steadiness from the place. It was as if I could finally share, was sharing, the success, optimism, confidence, heroism, and normality of the Israelis, simply by virtue of being among them. A Jewish tourist in the Jewish state, I was finally getting out of it only what I wanted and needed.

A temporary stage, enjoyable while it lasted. I took the train up to Jerusalem and wondered whether (as I’d been informed) there was really a sign in the car asking passengers not to lean out of the country. Jerusalem was still, dry, spooky, truncated. In the evening it was best to go out with a sweater. The super-pious in their black hats struck a bareheaded tourist as quaint, and the sky all day was deep blue from horizon to horizon, as in a painting by a child.

I took the bus to far-off Eilat. I relaxed, watching the reclaimed desert rush by, inhaling the aroma of fertilizer, then the unreclaimed, the lunar desert, and caught myself thinking, for the first time, This is mine. Eilat was the end of the world. The chick at a grilled fish joint was born in Baghdad in 1942, the same year as me, brought to the Jewish state at the age of eight, and had just finished her military service. She lifted her skirt for a quickie on the pebble beach of the Red Sea in the starlight, but wouldn’t take it off.

“Do all Americans wear glasses?” she wanted to know. And had I come to Israel to stay? Perish the thought. Israel was a nice country to visit, but who’d want to live there? That high point on the bus, that emotion of possession, of nearly belonging, was fleeting. If I’d come to find myself, then I could have no complaints—by the end of August, I had realized that, in the final analysis, as much as I admired my cousins, I wasn’t one of them and didn’t want to be. They were—how would I put it?—too different. I understood this when, on the bus back from Eilat, the radio blared a tune I could understand—it was Pete Seeger strumming his Communist banjo and singing, “This land is your land/This land is my land/From California/To the New York island…” I was pierced by homesickness.

And so it was that I sailed from Haifa with no regrets, and so it was that in May 1967, when the TV news relayed pictures of the mobs in Cairo waving death’s head banners and Arab armies mobilizing, I not only was afraid as I went about my business on the New York island, but could visualize the faces of the people I was afraid for, who had their lives on the line for me—the Yiddish-speaking garbagemen, the Iraqi girl whom I may or may not have knocked up, and, yes, even the philologist.