Diversity Debate

Silicon Valley’s Cynical Treatment of Asian Engineers

Asian Americans have become an unfun topic in Silicon Valley corporate life. Certainly, they embarrass the diversity-obsessed gurus at Google and Facebook.

Silicon Valley runs on Asians. This is a well-known aspect of the tech world in general, but it’s especially apparent in elite sub-sectors. Even by 2010, Asian Americans already had become a majority (50.1 percent) of all tech workers in the Bay Area: software engineers, data engineers, programmers, systems analysts, admins, and developers. Census Bureau statistics from the same year put white tech workers at 40.1 percent. Other races made up, in total, slightly less than 10 percent.

I interviewed a Facebook product manager fresh out of university. He interacts daily with teams of software engineers at Facebook, coordinating and leading projects, and getting them in line. Among the four teams of five or so software engineers he works with on a daily basis, he told me, 15 out of the 20 are Chinese. “I don’t mean Chinese-American,” he clarified. “I mean Chinese-Chinese, like from China.” These Chinese engineers largely speak Mandarin during work, making the company billions as they write code with machine-gun efficiency. Or, as he puts it: “We’re at an American social media company surrounded by Chinese [speaking people].” (In case you were wondering about the other five out of the 20, they were Asian American. “I think I might see one or two white software engineers here and there,” he added. “Not a single black or Hispanic [engineer].”)

Where else in America, besides NBA basketball maybe, are you going to find an elite field so dominated by one minority race? And just as basketball players are the core of the NBA business, software engineers are the core of Facebook. The company can survive without marketing managers or HR staff, but not engineers. Big Tech rises and falls with the quality of its technicians.

At surface level, you could spin this as a triumph of diversity: Attracting the best of the world’s talent, the American system welcomes people of different races to contribute to American business and society. The narrative of Asians making a difference at a huge American company such as Google or Facebook could be portrayed as a great feat, a demonstration of the American Dream at work.

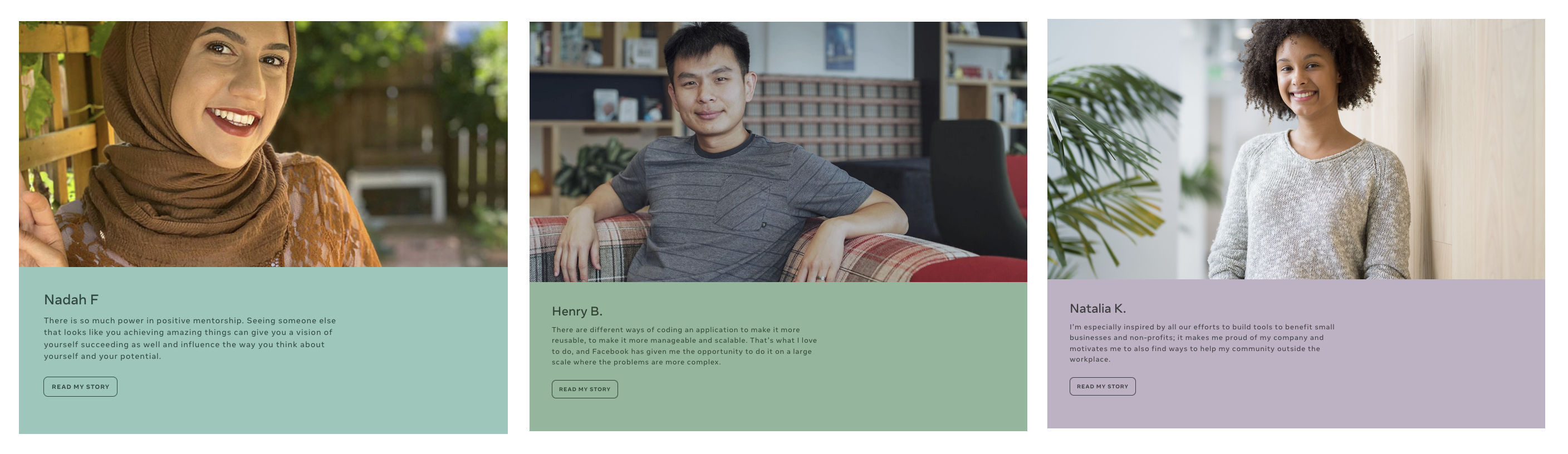

But that is not what happens. In press briefs and company images, we tend not to be treated to profiles of tech-team members—the core of these companies’ sky-high profits and market dominance. Facebook’s online diversity portal features nine stories. There are three people who appear to be black, and two who look distinctly Latino. Only one looks to be an East Asian person. His name is presented as Henry B.

Three of the nine staff stories contained in Facebook’s diversity portal

Little did Henry B. know that he would be the only East Asian person featured, standing in racially for half of all Facebook technical employees. The other employees’ stories and photos tend to feature bright lighting, full smiles, and gushing reports of how much they care about Facebook’s diversity platform. Henry B. has a dimly lit photo and a story that begins, “There are different ways of coding an application to make it more reusable.”

Asian Americans have become an unfun topic in Silicon Valley corporate life. Certainly, they embarrass the diversity-obsessed gurus at Google and Facebook. That’s because Asians are no longer considered “diverse” in the progressive tech world—despite unequivocally being a racial minority (6 to 8 percent of the total American population). Asian Americans represent 41.8 percent of Google’s workforce. Yet in Google’s 2020 Annual Diversity Report, Asian Americans are barely mentioned. Instead, the report comments on Google’s “increase[d] representation for women globally, and for Black+ and Latinx+ employees … We saw the largest increase in our hiring of Black+ technical employees that we have ever measured,” gushed Melonie Parker, Google’s chief diversity officer. (We are never told what a “Black+” person is.)

Following the document’s release, Forbes diversity writer Ruth Umoh summarized the report’s data as indicating both “modest gains in representation for women and people of color,” and “a disproportionately white, Asian and male workforce.” Since when did Asian people occupy the same space as whites? Many of these people’s parents were penniless immigrants fleeing communism just a few decades ago. On what basis should they be lumped in with white people, as if their historical experiences were similar?

A Facebook software engineer’s average starting salary is about $150,000 a year. That may sound like a lot. But outside of San Francisco, it’s probably equivalent to around $50,000 a year. And it’s pennies compared to how much these people are worth. Consider that there are only about 1,000 engineers at Facebook, yet Facebook’s annual revenue in 2020 was $86 billion.

There are a few reasons why Facebook and Google software engineers are so ignored and underpaid. First of all, Asian software engineers are often imported from other countries—China, in particular—through the H1-B Visa application process, which mandates that they must be sponsored by a US employer. The employer can revoke the sponsorship if and when it feels like it, and then the worker must get another job or leave the country. This means that companies such as Facebook and Google have leverage over their engineers, and can artificially depress their value (as well as the value of other people who work in the field). Secondly, Silicon Valley PR and business execs effectively exploit Asian stereotypes that present Asian software engineers as inherently disposed toward back-office work—the same stereotypes that Harvard University used to mark down Asian applicants on “positive personality,” courage, sociability, and other subjective measures.

There’s a scene in the 2015 film The Big Short in which actor Ryan Gosling, playing fund manager Jared Vennett, introduces an Asian financial analyst into the scene as a means to impress potential buyers. “Look at him,” he says. “That’s my quant” (a slang term to describe someone specialized in quantitative analysis). A greasy-haired Chinese-looking guy is shown with his shoulders hunched and a bewildered look on his face. “His name is Yang!” Ryan Gosling exclaims. “He doesn’t even speak English!”

“Yang” just sits there with a glazed look. And then, while the head honchos continue to talk, “Yang” faces the audience and says, in perfect English, “Actually, my name is Jung, and I do speak English. Jared likes to say I don’t because he thinks it makes me look more authentic.” It’s hilarious, but also a telling view of how elites see themselves in relation to Asian software engineers.

Unfortunately, this strategy of keeping down Asian talent works. By the time these “quants” realize their true value, when they maybe even get enough chutzpah to complain about it, they are fired or on their way out, and a naïve new Asian tech guy comes in to replace them. (The average tenure of a Google employee, remember, is just 3.2 years.)

According to publicly available 2020 data from Facebook itself, Asians make up 44.5 percent of the company’s total positions and 53.4 percent of what Facebook calls “technical roles.” (Technical roles include both the hardcore “software engineer” roles that are almost exclusively Asian-staffed, and the soft-core “data scientist” roles that tend to attract more white people.) But Asians make up just 25.4 percent of what Facebook calls “leadership” positions. That represents a nearly 50 percent cut in terms of Asian employees who start in the company and move up to leadership.

No other race exhibits the same low ratio. Black workers represent 3.9 percent of all roles at Facebook and 3.4 of leadership positions. Hispanic workers represent 6.3 percent of all roles and 4.3 of leadership. White people? Forty-one percent of all roles, and 63 percent of leadership.

When we measure whether a company has an “inclusive” climate, what are the statistics we really should be measuring? The percentage of people of various races who come in and start working for the company? Or the percentage who actually advance, who become leaders, and who drive the company’s focus and culture? Surely, the latter is more revealing.

Adapted, with permission, from An Inconvenient Minority: The Attack on Asian American Excellence and the Fight for Meritocracy, by Kenny Xu. Copyright © 2021 by Kenny Xu. Published by Diversion Books, a division of Diversion Publishing Corp.