Religion

Huxley, Burroughs, and the Church of Scientology

Like it or not, hidden within those influential texts are the bizarre jargon and lunatic assertions of a mendacious madman.

In the 21st century, Scientology has become a synonym for “cult.” Thanks to an array of investigative exposés and testimony from former members, few people in the Western world are unaware of at least some of the Church’s fantastical beliefs and more alarming behaviours. Sixty years ago, however, it was viewed quite differently. Scientology—or dianetics, as it was originally known—was an appealing idea to many intellectuals and creatives at a time when the world was rapidly changing and notions that had once been taken for granted were suddenly being tossed out of the window. In science, art, and philosophy, accepted norms were being turned on their heads, and in the 1950s and ’60s, L. Ron Hubbard’s ideas—peddled as an alternative to psychiatry—fit quite nicely among the emerging doctrines dreamed up by his contemporary thinkers.

Indeed, the original concepts that launched Hubbard’s movement were not as outrageous as those that define it today. Among these, the idea of “engrams” and the “reactive mind” were perhaps the most appealing. Hubbard theorised that humans are marked by unconscious traumas that essentially pre-determine “aberrant” behaviour. Naturally, he claimed that his organisation held the key to removing these traumas and freeing people from a great deal of suffering. Stripped down to its fundamentals, dianetics seemed to be no more implausible than the strange new ideas espoused by Freud and Jung, or even those previously espoused by Nietzsche.

Of course, there were always oddball beliefs bundled in as well, and as the years went by, these became more prominent. Hubbard—a science fiction author prior to his metamorphosis into quasi-religious guru—enjoyed adding new elements of fantasy to his central theories, layering sci-fi storylines on top of one another until his movement had become an extravagant sort of space opera. The more obvious cult-like elements would emerge in due course: charging adherents for advancement in the organisation; trapping them with manipulation and blackmail; the development of esoteric jargon known as “Scientologese” that made it almost impossible for real communication to take place between members and outsiders; and shocking campaigns of harassment against critics and apostates.

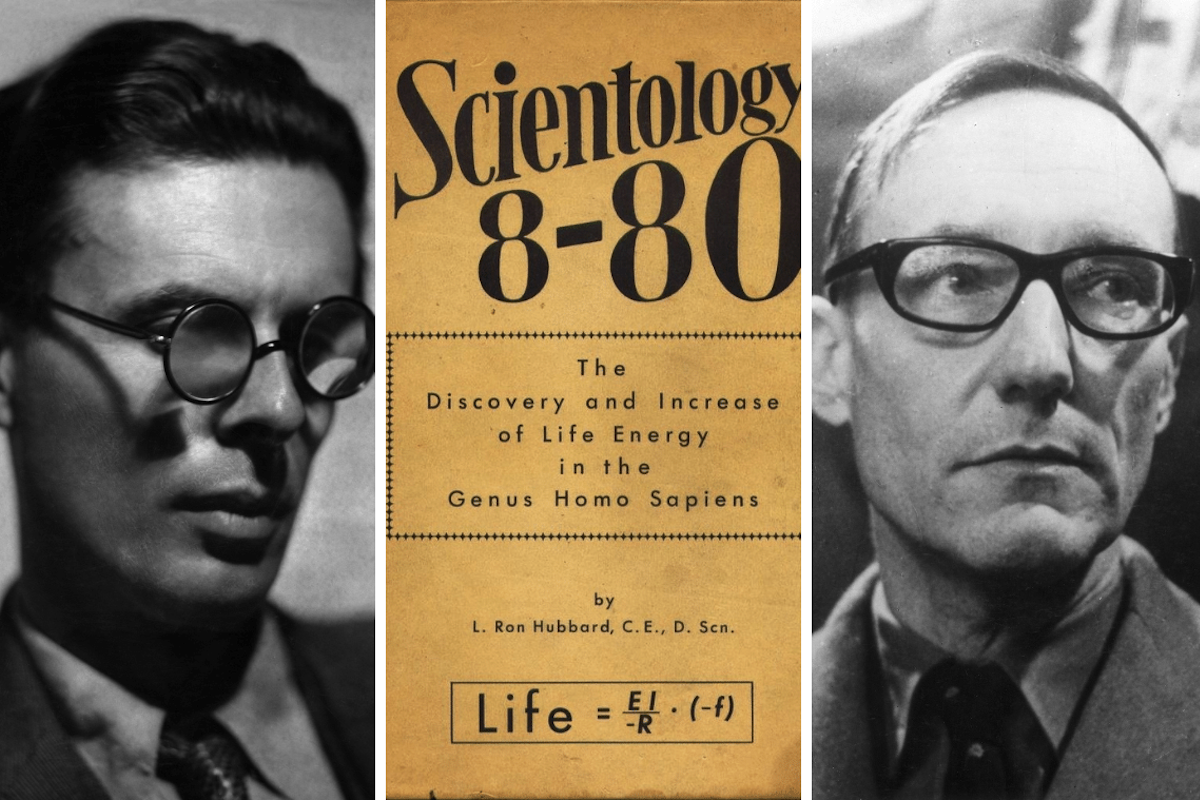

In the early days, however, none of this was particularly obvious. Hard as it is to believe now, many intelligent people were once drawn to Scientology out of an overabundance of curiosity, and its absurdities were generally perceived as harmless, affable eccentricities. Among those lured into the fold of this mysterious new organisation were two of the most important authors of the 20th century: Aldous Huxley and William S. Burroughs. Although Hubbard’s own novels elicit little more than derision from critics, his ideas wormed their way into some very influential books and left an indelible mark on American literature.

When people first hear about Huxley’s and Burroughs’s interest in Scientology, they typically express some degree of shock and/or scepticism. These men were highly intelligent thinkers famous for their insightful criticisms of the dominant culture. And both wrote extensively on the topic of coercion—Huxley was keenly aware of how humans could be manipulated into subservience by technodictators, and Burroughs was fascinated by the idea that language could be employed for the purposes of mind control. How then could they have fallen for the very thing they critiqued?

The reasons are quite obvious, in fact, and not especially different from those offered by the majority of ordinary people who fall under the sway of a cult. Like so many suckered by predatory organisations, both Huxley and Burroughs suffered from deep traumas. In spite of their formidable intellects and capacity for scepticism, they were both prone to suspending belief when it came to potential cures for their own existential angst. A quick glance through their biographies shows that both men were fooled from time to time by embarrassingly transparent swindles in the vain hope of finding transformation or redemption.

Aldous Huxley first discovered Scientology before it was even given that name. In 1950, he met with L. Ron Hubbard, who visited Huxley’s home in Los Angeles and personally administered the author’s first auditing sessions. Huxley and his wife Maria were both plagued by health problems and had pursued a number of pseudoscientific channels in the hope of a cure. Hubbard’s new movement, dianetics, appealed to them more than any other quackery they had encountered. Although Huxley immediately realised that Hubbard was “rather immature … and in some ways rather pathetic,” he respected his recently published book, Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health.

Hubbard’s ideas (and ideas he had stolen from others and passed off as his own), made their way into Huxley’s landmark 1954 study, The Doors of Perception (a book Hubbard said he admired, in spite of his movement’s vehemently anti-drug stance). Although Hubbard is not mentioned by name, references to his theories are scattered throughout its pages. Huxley talks about a gap between words and what they represent, and the importance of thinking in images rather than words—ideas discussed in Dianetics and its follow-up, Science of Survival. And Huxley uses the term “is-ness,” one of many neologisms coined by Hubbard who liked to append “-ness” to various words. Huxley wrote that “Each person is at each moment capable of remembering all that has ever happened to him.” In Dianetics, Hubbard wrote, “Wide awake and without drugs an individual can return to any period of his entire life.” When Huxley said that the fundamental goal of human beings “is at all costs to survive,” this was another reference to Dianetics: “The first law of dianetics is a statement of the dynamic principle of existence. THE DYNAMIC PRINCIPLE OF EXISTENCE IS: SURVIVE!”

Generations of readers have simply understood The Doors of Perception to be a book about a mescaline trip, infused with a little Eastern spirituality. However, in addition to drawing upon Hubbard’s ideas and language, Huxley may have been undergoing dianetic processing during his trip. He repeatedly refers to his “investigator,” who prompts him to answer questions and focus on different objects, while recording everything that happens on tape. Maria Huxley and the psychiatrist Dr Humphry Osmond were with him during the eight-hour episode. It is not clear who the “investigator” was and only a few questions remain in the written record, but it is possible that Maria was auditing him. In any event, just a year and a half later, Huxley would excitedly write to Osmond to inform him of a similar experience, only this time he reported that he had mixed dianetic processing with LSD.

Despite their dedication to dianetics and their shared conviction that it was ameliorating their health problems, Maria Huxley died of cancer shortly after the publication of The Doors of Perception. However, she had groomed another Scientologist, Laura Archera, as her successor, and after Maria passed away, Laura married Huxley and continued auditing him. Huxley referred to her as “my dianetic operator,” and in October 1955, she administered 400μg of LSD as she performed her dianetic processing. The experience was life-changing. Huxley already had a great affinity for hallucinogens and dianetics, but this experience compounded them. He wrote that he became aware of the “primordial cosmic fact of Love.” Although he acknowledged the absurdity of Scientology as an organisation, he was more convinced than ever that its core notions were of great importance and needed to be shared with the world.

Shortly afterwards, Huxley began work on a novel entitled Island, intended as a counterpoint to Brave New World. While the latter was a dystopian novel, the former was an attempt to express its author’s new visions of utopia, in which he explained what he believed would make the perfect society: a mixture of sex-positive attitudes, hallucinogens, and dianetics. Of course, the term “dianetics” never appears in the novel, but there can be little doubt about its influence. Island is crammed with Hubbard’s ideas and his annoying cult jargon. At the start of the story, the protagonist becomes aware of a system of “psychological first aid” that closely resembles dianetic processing. A young girl forces him to repeat a trauma over and over until its pain ceases to have any effect, which is exactly how Scientologists supposedly negate engrams. Soon, it is revealed that the entire population of the island is free from the pain caused by past traumas due to their reliance upon a range of dianetic procedures, and the trees are filled with mynah birds that call out “Attention!” and “Here and now, boys!” to help people remain “in present time”—a Hubbardian phrase that appears frequently throughout Dianetics and in his numerous lectures and papers.

Aldous Huxley died in 1963, the year after Island was published, but Scientology cast a longer shadow over the oeuvre of William S. Burroughs, influencing a great many of his novels and articles, as well as his audio recordings, film projects, and visual art. Burroughs came to Scientology in 1959 through his friend, the painter Brion Gysin, who had in turn been introduced by John Cooke—one of Hubbard’s first disciples and the man who persuaded him to transform dianetics from a so-called science into a so-called religion (a manoeuvre that allowed him to evade lawsuits and taxes). At the time, Burroughs and Gysin were living in Paris at the Beat Hotel, a flophouse filled with artists and writers, where they engaged in various odd practices, many of which involved the occult. It was Gysin who accidentally uncovered the Cut-up Method, which he taught to Burroughs, who popularised it in his own writing.

The discovery of the Cut-up Method is famous for its cultural ramifications. After Burroughs explored it extensively in his own work, it was adopted by a number of musicians, including David Bowie and Bob Dylan. But in the days and weeks after its discovery, any mention of it was conspicuously absent from Burroughs’s correspondence, except for a letter to Allen Ginsberg, in which he suggested that it was related to Scientology:

I have a new method of writing and do not want to publish anything that has not been inspected and processed. I cannot explain this method to you until you have the necessary training. So once again and most urgently (believe me there is not much time), I tell you: “Find a Scientology Auditor and have yourself run.”

Gysin was only mildly interested in Scientology, but Burroughs took to it immediately, incorporating Hubbard’s jargon into his letters and other writings within days of hearing about it. After reading Dianetics, he began to change his own personality, treating his friends coldly and sending them confusing, insulting messages. As with many cult members, he soon struggled to relate to those who did not share his new obsession, and this was partly due to its language. Hubbard wrote in a bizarre style that was almost unintelligible to non-Scientologists, and Burroughs, who began devouring anything and everything Hubbard had ever written, quickly incorporated this into his own vernacular.

Hubbard was a master of thought control and used language to manipulate his followers, who came to think and dream in “Scientologese.” In addition to his fondness for the “-ness” suffix, he liked to change verbs into nouns, employ abbreviations and obscure acronyms, and change the meaning of everyday words (as demonstrated even in his most accessible book, Dianetics) to what he believed the meaning should be, thereby subverting his followers’ use of language to give him control over their speech and thoughts. Over time, techniques like these came to dominate Burroughs’s writings, contributing to that most common of criticisms—that his books are incomprehensible.

Like many self-professed sceptics, Burroughs was tremendously gullible and applied his scepticism selectively. He was obsessed with what he called facts, but a fact was simply something that fit his peculiar worldview. His life story is littered with bizarre theories and obsessions that reside on the far fringes of science and common sense, from magic to telepathy to astral travel. Much of this can be attributed to the fact that he was a profoundly damaged person. Burroughs had been traumatised by various events in his life, including sexual abuse as a child, conflicting feelings over his own homosexuality, a decades-long battle with heroin addiction, and of course the accidental killing of his wife, Joan Vollmer, in 1951. Through a range of chemicals and pseudoscientific practices, he repeatedly sought to “change fact” and rewrite history to free himself of the pain that crippled him. Scientology, with its promise of freedom from past traumas, was made precisely to ensnare people like him.

From the beginning, Burroughs viewed Scientology as important in his life for two reasons: to cure his various ailments and to help him write better. Within a year of discovering Scientology, he was freely employing Hubbard’s ideas and language in his own writing. He found that he could cut up Scientology papers and use them for poems and novels, and Hubbard’s peculiar theories of engrams and human nature came to dominate the 1960s Nova Trilogy: The Soft Machine, The Ticket That Exploded, and Nova Express. All three books are peppered with explicit and subtle references. Burroughs even promoted Scientology in interviews, articles, and a column he wrote for the men’s magazine, Mayfair, in which he explained another of the new religion’s apparent advantages:

The importance of L. Ron Hubbard’s theories as expressed in his book Dianetics and a number of subsequent books and bulletins is enormous. It is no exaggeration to say that anyone who wants to understand the destructive techniques used by the CIA and other agencies official and private must read Hubbard’s writings and must read them carefully.

Ironically, Burroughs believed that this predatory new cult offered a means of escaping mind control. He was incredibly paranoid about perceived agents of that control, including the CIA and the FBI. His theories are too vast and convoluted to explain properly here, but in short he believed that even human language was part of a system (possibly created by aliens) that reordered human thoughts. Scientology, he decided, was the key to liberation.

In 1967, Burroughs signed up for a short course at the Church of Scientology’s London Org, which may have been an attempt at investigative journalism. Although he was mesmerised by Hubbard’s ideas, he remained fundamentally opposed to most structured organisations and retained some suspicion about “the Church.” However, the course persuaded him that Scientology was virtually perfect, and soon after, he signed up for various advanced courses. In one of his essays about Scientology, Burroughs sought to address criticism that the Church was brainwashing people, but it seems quite obvious that he had already been brainwashed:

An accusation brought against Scientology in the press is of course “brain washing,” the implication being that anything which alters thinking is bad by nature. It is of course understandable that those individuals who profit from keeping the public in ignorance and degradation do not want their thinking altered in any way and most particularly not in the direction of freedom from past conditioning which they have carefully installed.

Burroughs studied for several months at Saint Hill Manor and then continued in Edinburgh, where he attained the rank of Clear, a designation intended to indicate that an adherent has attained control over their own mind. During this time, he wrote a great deal of glowing praise for the organisation and its practices, but little of this was ever published except in Scientology’s own publicity materials. Then as now, the induction of celebrities was a coup, and the organisation advertised its ability to lure public figures. Burroughs was a major catch.

In his essays for the Church, Burroughs emphasised how much Scientology processing had helped him as a writer. It had helped him develop the Cut-up Method and had guided several of his most important and experimental novels. But it also helped him move in a new direction. “After Level VI and Clear I was able for the first time to handle my specific disabilities as a writer,” he explained. “I realized that my writing had become over-experimental and that I was out of communication with my readers.” Going forward, his writing became more accessible although he continued to rely upon Scientology for many of his ideas, using the E-meter to help him plot The Wild Boys.

Despite his initial enthusiasm, it was perhaps inevitable that he would not last long as a paid-up member of a cult. Although he never lost faith in dianetic processing or the supposedly therapeutic properties of the E-meter (what adherents call “the tech”), he eventually fell out with the organisation over its strict rules. He was particularly disturbed by the treatment of people labelled “suppressive persons” (malevolent individuals hostile to the Church and its mission) and the humiliating punishments and security checks meted out to loyal members for even the tiniest of infractions. When he began to distance himself from the Church and gave away the material he had paid for on his own courses, he was found guilty of “treason” and kicked out. This sparked a war between the writer and the cult, and he argued publicly with various high-ranking officials, including L. Ron Hubbard and his wife.

Most Burroughs fans are surprised to learn that he was ever a Scientologist. To their knowledge, his association with the cult was limited and his most famous writings on the subject come from the years after he was banished, when he published a number of assaults on the organisation, including his book, Ali’s Smile/Naked Scientology. To many, he is considered a hero for his anti-Scientology stance and his various attacks on L. Ron Hubbard, with his decade-long obsession covered up or played down. This is understandable—after all, it is not pleasant to think of your idols as credulous cult inductees. Yet Scientology was behind the creation of his most famous literary device; it guided the language, plot, and themes of his celebrated Nova Trilogy; and it continued to crop up in his work throughout the rest of his life.

Indeed, it is rare to find people who are aware of the extent of either Burroughs’s or Huxley’s relationship with Hubbard’s movement, let alone the uncomfortable fact that Scientology influenced their writings. In 2021, it is hard to imagine an intelligent person subscribing to a silly space cult that drains its adherents of their life savings. It is a club for the vulnerable and lost, and for vain Hollywood celebrities whose egos and insecurities are easily manipulated. Yet some of the 20th century’s most influential books were inspired by Scientology and sought to promulgate Hubbard’s teachings. Like it or not, hidden within those influential texts are the bizarre jargon and lunatic assertions of a mendacious madman.