Australia

Australia's COVID Catch-22

Australia has every advantage under the sun: plentiful economic resources, a highly skilled workforce, and traditionally competent governments.

Last year Australia was a COVID-19 success story. Just 30,274 cases and 910 deaths in 26 million people was something to celebrate. But now America and Europe are getting on with vaccinations and learning how to live with the virus. Australia is faltering with embarrassingly few vaccinations and new lockdowns.

It’s become like a Groundhog Day, set in late March 2020. In recent weeks community transmission has returned after leaks from hotel quarantine. This has led risk-averse state governments to reintroduce stay-at-home orders: first in Melbourne, and now in Sydney, Brisbane, Perth, Darwin, Townsville, and the Gold Coast.

Australia’s vaccination rate is at the bottom of the OECD’s 38 advanced economies. Fewer than five percent of Aussies have been fully vaccinated—12 times fewer than Israel, nine times fewer than the United States and the United Kingdom.

Australia has experienced the archetypical story of hubris. Aussies genuinely felt superior watching the rest of the world last year: we beat the virus, you got millions of deaths. The early success, however, bred arrogance and complacency. Now the overconfidence is coming crashing down in the face of failure.

Australia never expected to be so successful in suppressing COVID-19. Like elsewhere, the original plan in March 2020 was to “flatten the curve” to ensure healthcare capacity was not overwhelmed. This meant accepting that some level of spread was inevitable. This all changed when early border closures—along with harsh lockdowns and effective testing and tracing—unexpectedly drove cases down to zero.

Life quickly returned to normal for most Aussies; with the exception of an extended lockdown in Melbourne last year. The economy has performed better than most comparable countries and few have died. Dr Anthony Fauci, the US’s top infectious disease expert, “wished” the US could be more like Australia.

This sense of Australian exceptionalism drove complacency when it came to vaccines. The United Kingdom and the United States, in the face of large outbreaks, offered big money to speed up vaccine research and manufacturing. This meant signing big early contracts with a diverse array of producers using various technologies. Despite having plentiful resources, Australia was slow to procure, under invested, and opted for a heavily nationalistic approach. Then there was extraordinary bureaucratic failure and bad communications.

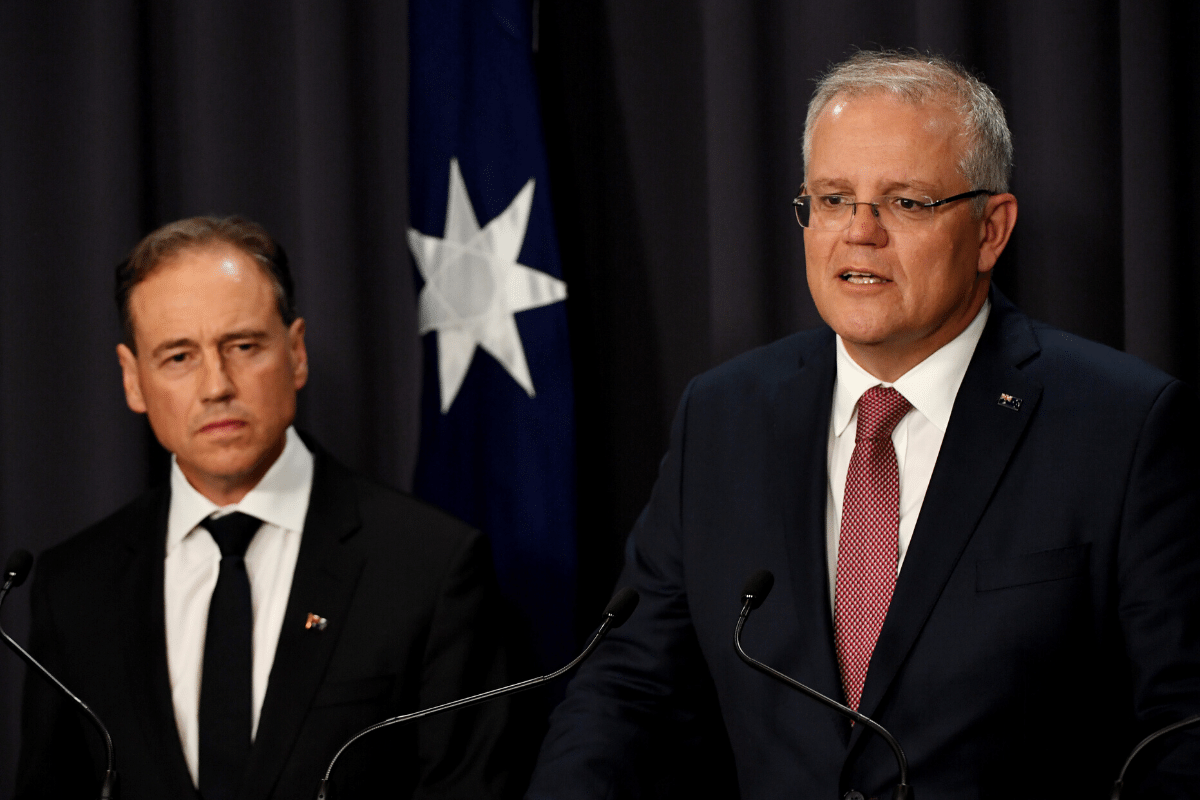

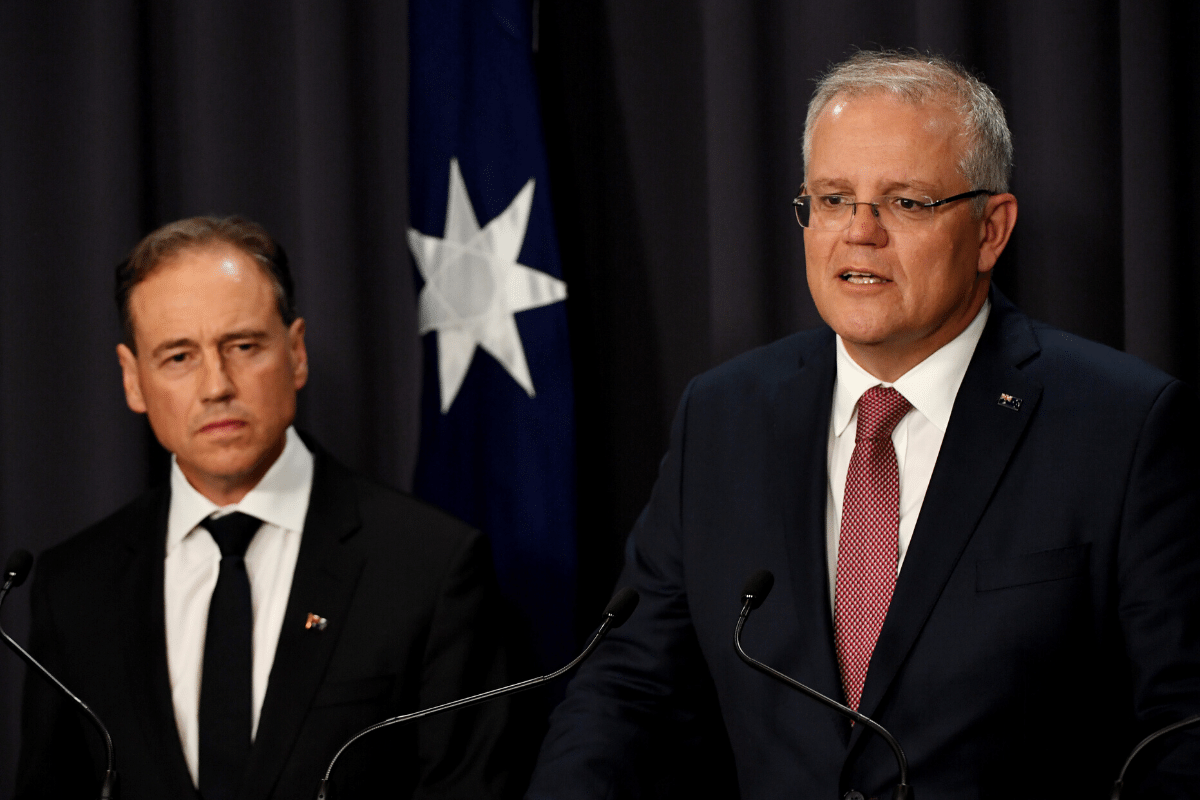

On November 5th, Prime Minister Scott Morrison proudly declared that Australia would be at the “front of the queue” for vaccines. A few days later, Pfizer announced the first highly safe and effective vaccine. This was followed in quick succession by Oxford/AstraZeneca and Moderna. At the start of December, the UK became the first country in the world to vaccinate with an approved vaccine. So what was happening in Australia? Nothing.

The approval of vaccines overseas marked the beginning of outward complacency from Australia’s political leadership. Morrison insisted in December that Australia would not take “unnecessary risks” by immediately approving vaccines. They would instead give Australia’s medical regulator—the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA)—as much time as they would like. The lack of urgency is astonishing. Morrison has repeatedly declared “It’s not a race” over the last six months. It is almost like there is little interest in reducing the risk to human life, ending damaging lockdowns and reopening borders.

The TGA did not grant approval for the Pfizer vaccine until January 25th—11 weeks after it was confirmed that the vaccine was safe and effective. AstraZeneca was not approved until February 16th and Moderna did not even get the tick until last week. This is despite perfectly competent, conservative regulators in the US, UK and Europe approving the same vaccines much earlier. It’s frightening to realise that the TGA would have been incapable of rapidly approving vaccines if Australia was experiencing a large outbreak in early 2021.

Even after regulatory approval, the rollout showed little urgency. It took an entire month for Australia to even begin vaccinating. Since then every target has been missed. The original aim was for a measly 60,000 by the end of February—just 30,000 were provided. It was then meant to be 3.4 million by the end of March. Just 600,000 were provided. “Australia falls 85% short of vaccine delivery goal,” the BBC reported at the time. Aged care staff and residents—the most vulnerable—were also meant to be jabbed by the end of March. This has still not been completed. In May, an aged care worker at a centre tested positive for the virus. Australians were meant to be fully vaccinated by October. It’s now not even on track to be completed before the end of the year.

The first major issue has been supply shortages driven by lacklustre procurement decisions.

Australia was meant to be largely dependent on locally manufactured AstraZeneca. But even this arrangement was not secured until September 2020 with manufacturing meant to start in March 2021. The government also heavily invested in a University of Queensland vaccine candidate that had to be cancelled after it produced false positives for HIV. This would be supplemented by a limited number of imported AstraZeneca (3.4 million), Pfizer (10 million) and Novavax (40 million). Novavax is yet to deliver a single dose. It took until 2021 for substantial expansion of Pfizer orders and not until last month was there a Moderna order.

Some of Australia’s vaccine woes were bad luck. Earlier this year, the European Union banned AstraZeneca exports to Australia over concerns about failure to meet contractual obligations to supply the bloc. This delayed the initial supply. Domestic production has also not lived up to expectations, with the one million doses per week goal not met. Then there was the medical advice against using AstraZeneca for younger cohorts due to rare blood clotting. Nevertheless, a wider portfolio of vaccines—rather than putting most of Australia’s eggs in the AstraZeneca basket—could have spread the risk and limited the impact of these hurdles.

But even with supplies growing, the rollout logistics has been chaotic.

Australia’s federal government took responsibility for vaccination procurement and delivery. The states, despite having vastly more service delivery experience and managing the annual influenza vaccine, were only initially tasked with healthcare and quarantine frontline workers. The federal health bureaucracy hired expensive consultants and contracted out provision. There were no initial plans for mass vaccination centres, despite proving successful in other countries.

These plans quickly fell apart because of a severe lack of organisational planning. The federal government struggled to provide delivery schedules. The states, GPs, and aged care facilities have complained about not knowing when doses will arrive, delays, and errors, making it difficult to organise appointments. There is still no national booking system, leaving people scrambling calling individual doctors’ practices and navigating lacklustre state booking systems. Some plans have changed: the original prioritisation list has been abandoned and states have been tasked with constructing mass vaccination centres. It’s also difficult to figure out what is happening due to a lack of transparency, clear lines of responsibility, or accountability.

Taken together, it really makes you wonder what Australian governments were doing last year when there was little community spread and ample time to plan a speedy vaccine rollout.

Soon, however, the biggest issue will be the growing levels of vaccine hesitancy. The lack of urgency, general mayhem and lacklustre communications has severely damaged public confidence.

In most parts of the world vaccine hesitancy has decreased over the last six months as hundreds of millions of jabs have shown it to be both safe and effective. Not in Australia. In August 2020, a poll found that 88 percent of Australians said they would get a vaccine, the highest among 27 surveyed countries. By December 2020, this had fallen to 64 percent. By May 2021, 55 percent of Australians would definitely get a “safe and effective” vaccine while 28 percent would refuse. Another survey suggested a concerningly low 35 percent of Australians said they would currently get a vaccine. This low level of interest in the vaccine will make it extremely difficult to get anywhere near the herd immunity level and mean a large number of people will remain vulnerable.

The rhetoric highlighting Australia’s “slow and steady” approach to vaccination was meant to instil faith that proper process was being followed. Instead, it has backfired by raising concerns. In the process of justifying Australia’s slow rollout, Morrison repeatedly insulted key allies by insinuating their faster programmes were unsafe, rushed, and problematic. At one point, the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) was forced to issue a statement correcting Morrison’s false claim that the UK does not test each vaccine batch for purity.

The AstraZeneca blood clot issue has also proven challenging for Australia. Sensationalist media reporting has exaggerated the risk of death, driving broader concerns over the vaccine in all age groups. The technical advisory group came out against anybody under-60 getting AstraZeneca—leaving millions of unused doses in the country. In the latest dramatic twist, the federal government announced this week that it would allow GPs to provide AstraZeneca to people under 40 who are willing to accept the risk. This opportunity was immediately taken up by thousands of younger people who have the most interest in ending lockdowns and continuing with normal life. In response, however, Queensland’s chief medical officer Dr Jeannette Young dramatically played up the risk of an 18 year old “dying from a clotting illness” after taking the vaccine. The playing up of a minuscule risk has been heavily criticised for providing a big gift to antivaxxers.

But in a way Young is right. There is no point in getting a vaccine when borders are shut and there are few locally transmitted cases. It’s a Catch-22: you cannot open the borders until people are vaccinated, but there’s no point in getting your vaccination while the borders are shut. Australia is on the cusp of becoming the Hermit Kingdom. There is no prospect of international borders reopening until 2022. There are calls for harsh arrival caps to be halved. Closed borders remain extremely popular. It will take another 12 months for the completion of Australia’s vaccine programme at its current pace. Even then, Australians seem unwilling to accept even a single case of community transmission. Even vaccines are not 100 percent effective and cannot guarantee zero cases and so quarantine and lockdowns could continue for some time.

Australia has every advantage under the sun: plentiful economic resources, a highly skilled workforce, and traditionally competent governments. The challenge ahead is to transform these into meaningful action on the vaccine front and for politicians to provide leadership. Every effort should be made to learn from overseas—such as the latest trials showing that mixing vaccines is more effective—to speed up the rollout. They should call in the military logisticians behind Britain’s speedy rollout and the scientific expertise from the United States to expand manufacturing. It will then be necessary, once the population is vaccinated, to have an adult conversation about how COVID-19 is not going to disappear from the face of the planet.

Australia did well at the start of the pandemic. But learning how to live with the virus is going to take a little while longer.