Cinema

When Norman Jewison Turned His Camera on the Ultimate Superstar

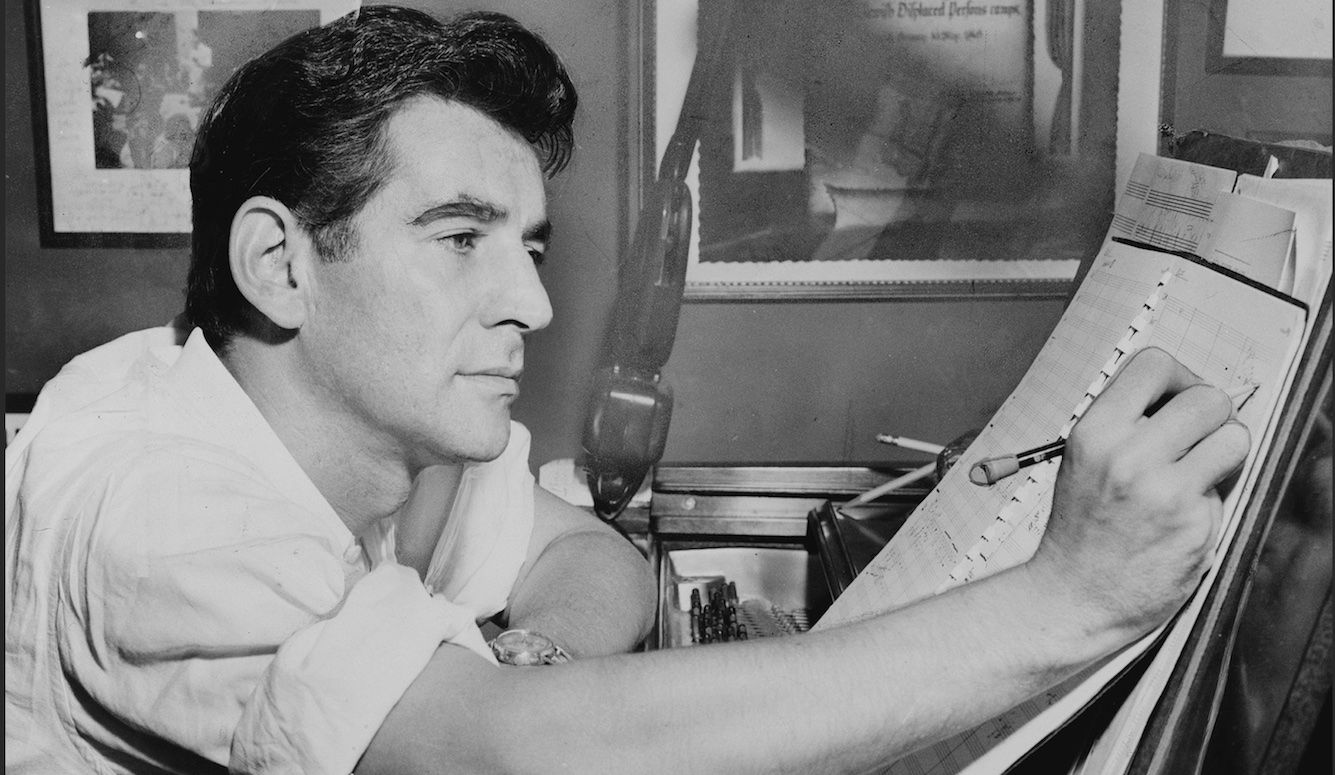

Jewison, by contrast, had found himself both “curiously moved” and “flooded with exciting visual images” upon first hearing the album.

While some critics would later struggle to find a thematic through-line connecting Norman Jewison’s films, the Canadian director often identified his signature theme as betrayal. His 1973 musical drama Jesus Christ Superstar, adapted from the 1970 concept album of the same name, allowed Jewison to tackle the archetypal betrayal narrative in Western culture while simultaneously creating something completely original: the first filmed rock opera.

Some thought it was an odd subject for a Jewish director. But contrary to popular misunderstanding (which can be traced in part to his 1971 adaptation of the Jewish-themed musical comedy-drama Fiddler on the Roof), Jewison isn’t actually Jewish. In fact, he grew up in Toronto as the son of a Protestant convenience store owner. Coming off his work on Fiddler, he joked to a friend, “I thought I should do something for the goyim.”

Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice had begun writing the songs that would become Jesus Christ Superstar in 1969, when they were still in their mid-20s. Rice was inspired by a few lines from Bob Dylan’s 1964 protest song, With God On Our Side:

Through many a dark hour

I’ve been thinkin’ about this

That Jesus Christ was

Betrayed by a kiss

But I can’t think for you

You’ll have to decide

Whether Judas Iscariot

Had God on his side

Before it was an album, musical, or film, Jesus Christ Superstar was a hit single. Attuned to the countercultural wavelengths of the time, the song was performed from Judas’s perspective, raising questions about Jesus’s motivation and about Judas’s culpability for a murder that was God’s will. Rice remembers sitting in his parents’ home one Sunday morning when he penned the final lyrics:

Did you mean to die like that, was that a mistake or

Did you know your messy death would be a record-breaker?

Don’t you get me wrong

I only want to know

Jesus Christ, Jesus Christ

Who are you? What have you sacrificed?

Jesus Christ, Superstar

Do you think you’re what they say you are?

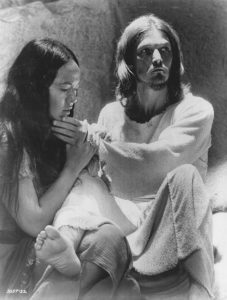

Lloyd Webber and Rice knew their material justified something big. The resulting Superstar album would approach timeless theological questions through the frame of modern celebrity culture. Perhaps Christ was the son of God; perhaps he was also a proto-rock star, the tabloid fodder of classical antiquity. Jewison would represent the character of Mary Magdalene as a kind of groupie: washing his feet, anointing him with oils, “in love with the idea” of Christ, Jewison said, in much the same way that young fans might dote on a “superstar.” Yet, as he told a Vatican Press journalist, Jewison also felt that Mary’s song I Don’t Know How to Love Him expressed “an emotion that is perhaps one of the most beautiful in the whole film, because many people do not know how to love Him—indeed many people do not know how to love anybody.”

But the Jesus Christ Superstar double-LP “Brown Album,” released in the UK in 1970, was a disappointment. “It was met with a massive dose of British indifference, even condescension,” remembers Lloyd Webber. “There were a few nice comments, but as there were no big names involved, I doubt if any of the major rock critics heard the whole thing out.”

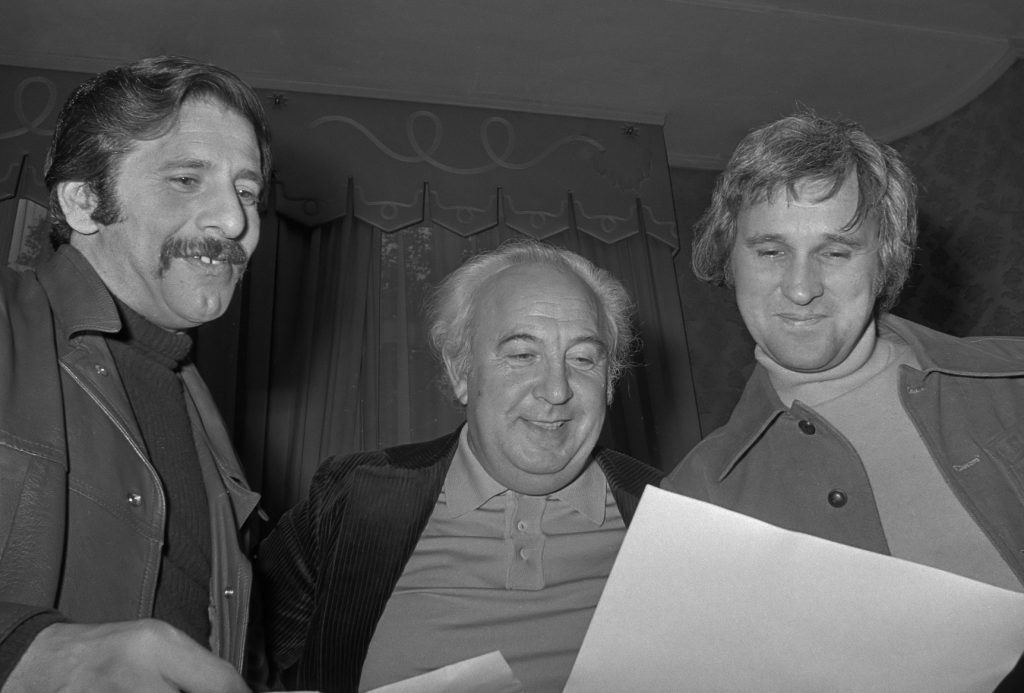

Jewison, by contrast, had found himself both “curiously moved” and “flooded with exciting visual images” upon first hearing the album. At the time, he was on location in Yugoslavia, where most of the exterior shots for Fiddler were filmed. Actor Barry Dennen, who had a bit part in Fiddler and voiced Pontius Pilate on the Superstar album, had given Jewison a copy. Associate Producer Patrick Palmer remembers Jewison’s excitement about this “obscure album from England … He said, ‘You’ve got to listen to this … I’m going to make a film out of it.’” Before long, Jewison set up a meeting with Lloyd Webber and Ned Tanen, an executive at Universal.

For Rice and Lloyd Webber, Jewison’s interest in Superstar was a major boon. Fiddler had given Jewison “street cred not only with steering a musical from stage to screen but also with a Jewish story,” Lloyd Webber recalls. Jewison seemed “the perfect fit and the meeting was positive as meetings always are in Hollywood. Ninety-nine percent of the time you leave buzzing with the fantastic power powwows you’ve had, and then never hear from anyone again, but this meeting proved the exception.”

From the outset, everyone agreed that the film would be “sung-through,” consisting only of the album’s songs with no added dialogue. Rice had first crack at the screenplay, and turned in a monumental Ben-Hur-style epic. He remembers approaching it as though it were simply “a question of pointing out which massive visual effect accompanied which song. Should the procession of camels enter from the left or right of the frame? What was the best marching formation for the Roman legions?”

But Jewison didn’t see Superstar as an old-fashioned sword-and-sandal epic. He wanted to devise a film idiom as hip and contemporary as the rock opera. He and the English novelist Melvyn Bragg developed a “pastiche” approach that blended the biblical and modern eras. A new framing device would deposit a theatre troupe in the Holy Land, where they spontaneously mount the passion play amidst the ruins. Jewison and Bragg drafted scenes while scouting locations in Israel, walking through desert locations listening to Superstar on a tape recorder, immersing themselves in the landscape and music.

Budgeted at slightly under US$3.5 million, Superstar would be Jewison’s leanest production in years. The actors eventually cast in the three principal leads of Jesus, Judas, and Mary, would make just US$16,500 each. Jewison took a significantly reduced director’s fee (at US$150,000) in exchange for 10 percent of the worldwide net profit. (The bet worked out: According to Palmer, the film had done US$40 million in business by the mid-1980s.) The low budget was made possible by the Israeli government, which offered a 23.5 percent rebate on foreign currency brought into the country. Jewison also received support from senior Israeli officials who were working to establish a new Israeli Film Centre. In return, Jewison recommended the experience of shooting in Israel in Hollywood trade publications. “There is a spirit in the country and among its people that grabs you,” Jewison wrote in an article for Variety, “and if you spend any time there you will never be the same.”

Principal photography of Jesus Christ Superstar began in the caves of Beit Guvrin, near the valley in which David is said to have killed Goliath, on August 18th, 1972. Today, the vast network of underground caves is part of Beit Guvrin National Park, although Jewison remembers that it “took days to clean out all the pigeon shit and bat dung” before they could begin filming the songs What’s the Buzz?, Strange Thing Mystifying, and Everything’s Alright.

Jewison had chosen for Christ’s refuge the vast, cathedral-like bell cave not only for its primal beauty but also for its implicit symbolism: Jesus and his Apostles were an “underground” movement, literally and figuratively. He’d cast the picture from top to bottom with unknowns—he told a casting agent he wanted “mainly young rock singers who can also act and dance”—just two of whom had prior film credits. A running joke was that their careers had taken them from Hair to Eternity.

Among the Hair alums was Ted Neeley, who’d played the male lead in the 1969 Broadway production (the full name was Hair: The American Tribal Love-Rock Musical). A rock-and-roll drummer from Ranger, Texas, Neeley wasn’t an obvious choice for the son of God; indeed, casting notes Jewison scribbled on a piece of Beverly Hills Hotel stationery reveal a list of actual superstars he was considering for the part, including Mick Jagger, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Barry Gibb, Ian Gillan, and Robert Plant. Sometime in 1971, Neeley’s agent invited Jewison to watch the singer perform in The Who’s Tommy in Los Angeles. Jewison, then in Palm Springs, made the two-hour drive to LA for an evening performance, only to discover that Neeley had the night off. Jewison returned to his hotel, irritated that he’d wasted his time.

“The next morning,” Jewison recalls, “I opened the door of my motel room to find a short young man in Levis wearing a false moustache and beard.” Neeley, wearing the cosmetics to show Jewison what he could look like with facial hair, had tracked the director down to apologize and explain that he’d been out sick. “I agreed to meet him for a coffee in the cafeteria and we chatted for 20 minutes,” Jewison recalled. “That afternoon on the plane to London I told Pat Palmer that I had a hunch that I had found our Jesus, and I hadn’t even seen him perform.” They would test more than two dozen actors for the role, but no one could match Neeley’s combination of swagger and vulnerability.

Jewison knew that he was courting controversy by casting singer Carl Anderson as Judas. As a member of the Vatican Press would ask: “Mr. Jewison, why did you choose a Black Judas?” His response was categorical: “I think discrimination is evil,” he said. Anderson “tested along with many others in London, and as always happens, the film really told us what to do. The test was so successful that there really wasn’t any doubt in my mind at all that he was the most talented actor to play the role.” (Elsewhere, Jewison conceded that “nobody would believe” that explanation, but he didn’t care). Yvonne Elliman, the exquisite 20-year-old Japanese-Irish singer from Honolulu who voiced Mary Magdalene on the album, would also embody the part in the film version.

From Beit Guvrin, the production moved to the “Occupied Area,” West Bank territory taken by Israel in the Six Day War of 1967. Robert Iscove, the film’s choreographer, remembers an incident where “Arabs with machine guns came over the hill, pointing at us. They were from a neighbouring village and there had been some tiff that had nothing to do with the actual war, but, the whole experience—I mean from beginning to end it was fraught.”

Everything about Superstar was infused with a sense of place. One of the main shooting locations was Herodian, a palace fortress built by Herod the Great between 23 and 15 BCE. On a clear day, Jewison could perch on the highest of the walls and see Bethlehem and Jerusalem to the north, and the Dead Sea to the east. He shot Jesus’s climactic number, Gethsemane, in which a spiritually tortured Christ implores God to reveal “just a little of your omnipresent brain,” amidst the imposing crags and cliffs of the Siluad Wadi. The area was completely inaccessible to the company’s buses and Land Rovers, so their generators, lights, and other production equipment was hauled in by donkey.

Sequences involving the Roman priests were shot at Avdat, a 2,300-year-old Nabataean city near the center of the Negev desert. Crews added a steel scaffold to create visual interest and foreground a sense of chronological tension, heightened in other scenes with tanks and jets on loan from the Israeli army. Jesus’s theatrical moment of tearing down the temple (“our little swing at the materialistic world,” Jewison recalls) contained images of modern weapons and a bag of marijuana—“Which there was a lot of around as I remember,” Jewison recalls.

In the end, Jewison used more than 20 locations from four base camps, in Jerusalem, Beersheba, the Dead Sea, and Nazareth. Not a single frame of Superstar was shot on a soundstage.

While a small handful of sequences, such as Herod’s number and the title song, were “absolutely set,” remembers choreographer Robert Iscove, most dance numbers were worked out on the spot: “We would get out to the set, see the environment,” and Jewison would say “this is what we’re doing today guys and the camera will be roughly over here,” and the rest was devised in relation to the landscape.

MTV was still a decade away, but Jewison’s camera, swirling around a wailing Jesus Christ perched on an Israeli cliffside in Gethsemane, provided an influential model for the music-video genre. Director Atom Egoyan, who’d become best known for his Oscar-nominated The Sweet Hereafter in 1997, remembers seeing Superstar “over and over again” at the Haida Cinema in Victoria, British Columbia. Superstar “was pretty fundamental in making me understand what a camera does,” Egoyan says. “The way the camera is moving, the way it moves in time to the music, the way the film is cut, the production design, the framing device … it was just brilliantly conceived as this pageant within a film.”

Much of the film’s sense of spiritual abandon reflects the heady atmosphere that presided among cast and crew that summer. Jewison had assembled a tribe of flower children in the Holy Land and completely isolated them from the secular world. They spent their days blasting the rock opera at deafening volume in the desert; when they weren’t working, they played beach volleyball: team Judas against team Jesus. The film had taken over their lives.

“We were all hippies, we were all kids,” remembers Iscove. Superstar “was bringing what we were doing in our personal act together with our craft … we were all reading the Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ,” a central text for New Age astrology. The average age on set was about 25.

Jewison, who turned 46 that summer, was no longer interested in pretending to be one of the kids. “Norman was a little bit of a fuddy-duddy,” remembers Iscove. “He didn’t spend a lot of time with the cast, and I don’t remember a lot of dinners or a lot of cast parties at that time. He did remove himself.”

With the crucifixion scene looming, the highly emotional, spiritually intoxicating vibe was almost too much for Neeley. He and other cast members believed that they were walking on the very soil upon which Christ had walked; that the thorns that pricked them were the same thorns that had made up Jesus’s crown. “The emotional power we experienced…” Neeley said, struggling to find the right words. “What was going on with us was emotionally overwhelming.” Neeley’s performance on the cross brought the cast and crew to tears. And he remembers falling apart emotionally after filming it.

While Rice and Lloyd Webber’s album had been denounced as blasphemous in many quarters, including at the BBC, which had banned it, Jewison’s film feels less confrontational, and contains more room for reverence. At times, Christ looks up and addresses the camera lens as God, in precisely the same way that narrator Tevye the Dairyman had in Fiddler on the Roof. The instant that Christ resolves to die, the viewer is assailed with a lightning-fast montage of canonical paintings by Goya, Tintoretto, Velázquez, Grünewald, Bosch, and others, evoking Christ’s agony on the Cross. The director may have had another montage in the back of his mind, one that included Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Bobby Kennedy: Jewison didn’t have to look 2,000 years into the past to find public figures who’d been killed for preaching peace.

Jesus Christ Superstar ends with an air of religious mystery: After Christ’s crucifixion, the performers, having completed their pageant, re-board the bus that will carry them back to 1972. The actor who played Jesus is not among them. When viewers first encountered this troupe, they’d leapt off the bus with wild ebullience; now, they seem burdened with a profound sense of loss. The film ends with the silhouette of an empty cross, a shepherd and his flock barely visible in the sunset. The credits roll in total silence.

“I am so convinced that in the hands of anyone else this film would not have had the magnificent spiritual content it does,” Neeley said of Jewison. “It is what it is, and it’s so simply stated that everyone can understand it.”

This essay is adapted, with permission, from Norman Jewison: A Director’s Life, published by Sutherland House. © 2021 by Ira Wells.