BLM

Black Lives Matter and the Psychology of Progressive Fatalism

There is nothing wrong with elevating anti-racism in one’s own life. But there is something wrong with imposing one’s moral reality upon total strangers.

Former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin has been convicted of murder, but the ramifications of his fateful encounter with George Floyd will reverberate through American culture and politics for years to come. The revival of the Black Lives Matter movement last summer produced the largest protest in American history and a groundswell of anti-racist activism across America’s major institutions. A year later, we can begin to see the ripple effects of what one Atlantic contributor has called the “Third Reconstruction.” More than 30 states have passed more than 140 police oversight reform laws; efforts are being made to introduce reparations for black Americans in various forms; and the progressive vision of racial inequality has penetrated American institutions and culture. Police are facing renewed pressure to perform their duties with discretion, and awareness of historical racism and its lingering effects has risen.

On the other hand, the homicide rate is soaring in cities across the country amid a historic surge of violent crime—in Minneapolis, for example, the murder rate has returned to the days when the city was dubbed “Murderapolis” by parts of the national media. Meanwhile, ongoing waves of rioting and looting have inflicted catastrophic damage on many urban districts, and the stirrings of a cultural backlash were evident in the January 6th insurrection on Capitol Hill. Moreover, this “racial reckoning” has set in motion a litany of cancelations, including the absurd firing of eminent New York Times science journalist Donald McNeil for mentioning a racial slur in a benign context. Worse, a year of anti-racist agitprop has left Americans more suspicious, polarized, and disdainful of opponents than before.

And so, the culture war rages on—the latest front is a fight over whether or not critical race theory should be taught in schools, and another summer of upheaval appears to be underway. What the outcome of all this will be, no one can honestly say yet, but the signs are not encouraging. What can be said, however, is that last year’s racial activism didn’t arise in a vacuum—it was made possible by a deepening progressive fatalism about race in America and the sharp cultural turn toward identity issues in the 2010s.

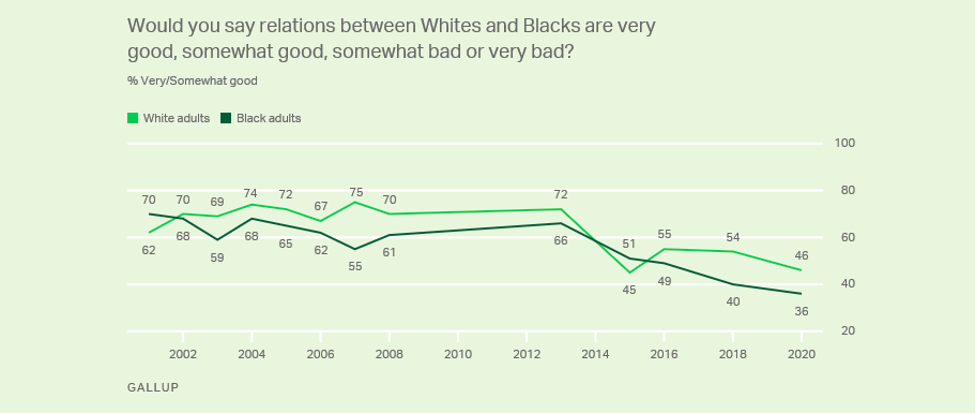

In 2013, for instance, 72 percent of white adults and 66 percent of black adults reported that race relations were either very or somewhat good, according to Gallup. By 2020, those numbers had dropped to 46 percent and 36 percent, respectively. The percentage of white Democrats who say that racism is a big problem in the US leapt from 52 percent in January 2015, to 89 percent by early June of 2020, a Monmouth University poll found, while the percentage of black Democrats who agreed rose from 69 percent to 93 percent over the same period. White liberals have recently become the only political-racial group in the country with a pro-outgroup bias in favor of nonwhites, and report more racism against blacks in the United States than blacks themselves.

As the work of political scientist Zach Goldberg has shown, the shift in progressive opinion on race is correlated with the explosion of social media and digital journalism. The percentage of Americans listing the Internet as their primary news source rose from 14 to 47 percent between 2006 and 2018, with progressives leading the way. And the ubiquity of camera-phones has allowed rare but distressing incidents of police misconduct to go viral, shifting attention from local news to national and global narratives and enabling a feedback loop of perpetual moral outrage.

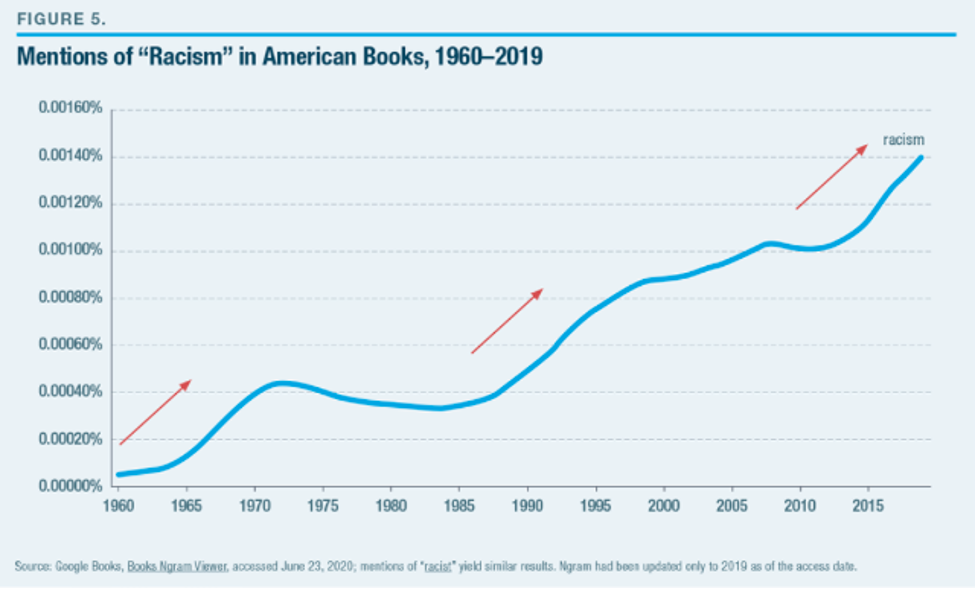

But technology offers only a partial explanation for the sea change in progressive politics. As politics professor and author Eric Kaufmann argues in a recent paper for the Manhattan Institute, “The Social Construction of Racism in the United States,” recent developments were preceded by two other consequential periods of radical racial activism—the late 1960s following the early successes won by the civil rights movement, and the late ‘80s and early ‘90s during the early debates over political correctness.

This growing preoccupation with race and racism is informed by an ideological urge to identify with historically victimized minorities against the majority. In his 2015 memoir, popular African American author Ta-Nehisi Coates claims, “The problem with police is not that they are fascist pigs but that our country is ruled by majoritarian pigs.” This has less to do with defending disadvantaged minorities per se, than indicting society and its history of white colonialism and patriarchy. In a long essay for the American Affairs journal entitled “Liberal Fundamentalism: A Sociology of Wokeness,” Kaufmann characterizes the liberal identity as an anti-majoritarian ethos which sacralizes historically excluded minorities according to race, gender, and sexual identity.

Debates about race—and anti-black racism, in particular—cut deeper than other issues in America. The legacy of American race relations conjures brutal recollections of bondage, subjugation, and atrocity spanning hundreds of years. The discrepancy between the Enlightenment ideals upon which the world’s oldest democracy was built and its participation in slavery and racial apartheid means the condition of American blacks is fraught with uniquely powerful feelings of symbolic national guilt. Moreover, anti-racism provided a paradigm for change in American society. The women’s suffrage movement was the offspring of abolitionism, and the civil rights revolution midwifed second wave feminism, gay rights, and other forms of social protest and group activism. Since the 1960s, “racist” has been among the worst epithets in American public life and anti-racism has developed into something resembling a national moral iconography, with its own set of symbols, myths, dreams, and taboos intended to purge the collective shame of historical racism in perpetuity.

Symbolism is by no means unimportant—it provides cultures with the emotional geography to navigate complex historical realities. But an over-reliance on metaphor can blind us to the accumulation of material change and preclude a balanced understanding of the present. Supporters of the Black Lives Matter movement argue that blacks are routinely killed by the cops because America hates them. After the first wave of protests last summer, the New York Times columnist Charles Blow wrote: “The protests are not necessarily about Floyd’s killing in particular, but about the savagery and carnage that his death represents: The nearly unchecked ability of the state to act with impunity in the oppression of black bodies and the taking of black life.”

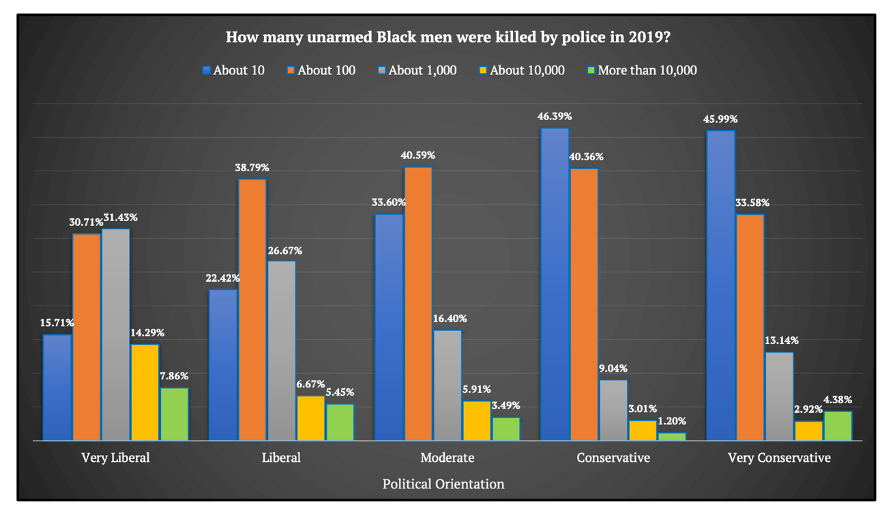

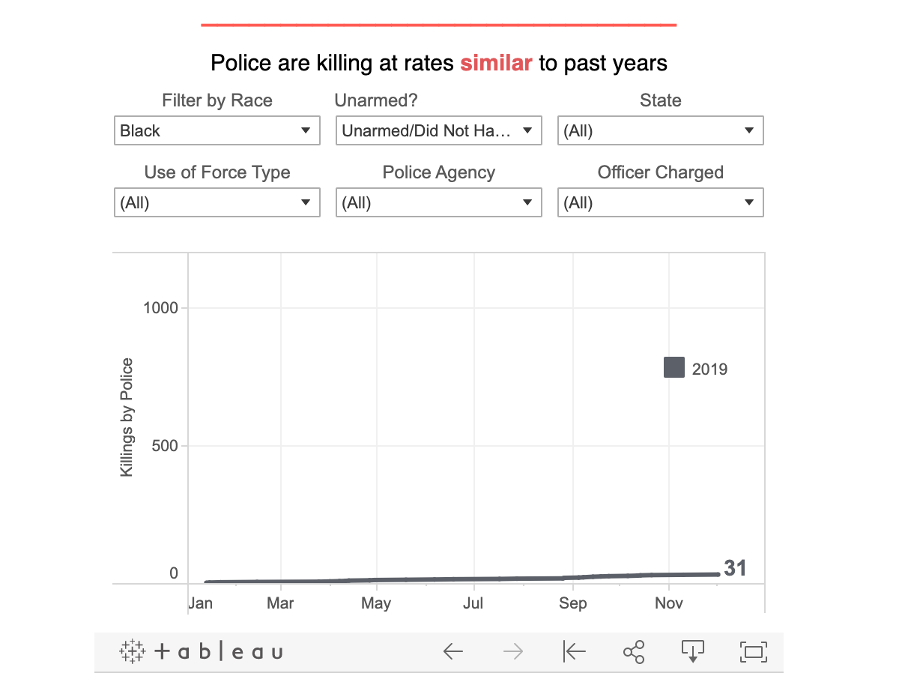

However, political narratives constructed on anecdotal evidence can create and fortify highly misleading impressions. A recent survey by the Skeptic Research Center asked participants across the political spectrum how many unarmed black men were killed by police in 2019. These were the results:

The correct answer, according to the Mapping Police Violence database, a project curated by activists, is 31 (the Skeptic Research Center reports 27, so presumably the MPV data has been updated since the SRC report was published):

The Skeptic Research Center’s report cautions that “Existing databases are compiled from a central dataset, the FBI’s National Use-of-Force Data Collection. Critically, this data collection effort was established only recently in 2019, law enforcement participation is voluntary and, as of 2020, only 5,030 out of 18,514 federal, state and local law enforcement agencies have provided use-of-force data.” Nevertheless, the gap between perceptions and reality is vast and grows the more “liberal” and less “conservative” the cohort questioned.

In addition to which, the percentage of young black men killed by police has declined since the late 1960s by about 80 percent, according to an extensive data analysis by the Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice. And despite considerable evidence that police are more likely to pull over, harass, search, and otherwise mistreat black Americans compared to other groups, multiple studies have found no evidence of bias in police shootings of black suspects once the rate of encounters between police and civilians have been accounted for. Reporting on his study in the New York Times, behavioral scientist Sendhil Mullainathan concludes, “If police discrimination were a big factor in the actual killings, we would have expected a larger gap between the arrest rate and the police-killing rate. This in turn suggests that removing police racial bias will have little effect on the killing rate.”

Even if racial bias really were the problem, there doesn’t seem to be any readily available solution. Implicit bias training doesn’t really work, racial sensitivity programs tend to backfire, and white police officers are no more likely to kill minority suspects than black police officers. Meanwhile, black Americans are about 30 times more likely to be killed by fellow citizens than police, as the writer Andrew Sullivan has observed. In a stroke of tragic irony, the widespread perception that police are a net negative for black people may result in more black homicides by reducing police presence in high-crime minority communities. Eighty-one percent of black Americans say they want more or the same amount of police in their neighborhoods.

On its face, there’s something odd about launching a nationwide movement around an issue that is rarer than being struck by lightning, has no obvious solution, has been rapidly improving, and ignores a far worse problem. But it’s less strange in the context of a culture obsessed with untethering itself from its own history. It is the symbolism of a white cop killing a black suspect that arouses collective moral indignation. If Derek Chauvin had been black, or if George Floyd had been white, it’s worth wondering whether or not the latter’s death would have elicited the same response.

In fact, unarmed white Americans are killed by police in comparably egregious circumstances and at a similar rate, but such incidents seldom elicit the same degree of public condemnation. The racial double standard is felt to be justified in light of—and as a corrective to—the racial double standards of America’s past. Since racism disfigured much of our history, it seems appropriate to many people that we remain especially vigilant to circumstances that in any way resemble that history. The price we pay for looking at the present through the lens of the past is a failure to understand the relationship between them. The desire to escape history can trap us inside it.

Surprisingly, the most radical forms of activism often emerge after demands for reform have been met or set in motion. Black Power arose in the late ‘60s following the tangible victories of the civil rights movement in the previous half-decade; LGB and radical trans activism grew after gay marriage rights were secured at the federal level; race pride and identity extremism in post-colonial Africa flourished after nations slipped the Western yoke; Black Lives Matter was founded after America’s first black president was elected. As the writer Shelby Steele put it, “Anger in the oppressed is a response to perceived opportunity, not to injustice. And expressions of anger escalate not with more injustice but with less injustice.” Underlying this phenomenon is a sense of disappointment. Even in the face of obvious progress, democratic societies remain flawed and unequal in a number of ways. So, what if the problem is society itself? Fatalism takes hold and empowers the demand for the most extreme measures like de-funding the police.

Before 2008, many believed the country was simply too racist to elect a black president. And then, just like that, it happened and Americans forgot what it felt like before it happened. For progressives, the optimism that came with a two-term black presidency in a white majority country with a recent history of overt racism was thwarted by the realization that racism hasn’t gone away and black disadvantage abides. Nothing inspires bitterness like shattered expectations. The mistake was expecting the arrival of utopia in the first place.

In Obama’s second term, Ta-Nehisi Coates entered what he called a “Blue Period,” during which the tone of his commentary shifted from liberal optimism to thoroughgoing pessimism. To Coates, the resistance to the Obama presidency on the Right and the subsequent election of Trump simply confirmed his suspicion that America is terminally afflicted with the virus of white supremacy. In his 2017 collection of essays We Were Eight Years in Power, he wrote:

It is hard to remember the excitement of that time, because I now know that the sense we had that summer, the sense that we were approaching an end-of-history moment, proved to be wrong. It is not so much that I logically reasoned out that Obama’s election would author a post-racist age. But it now seemed possible that white supremacy, the scourge of American history, might well be banished in my lifetime. In those days I imagined racism as a tumor that could be isolated and removed from the body of America, not as a pervasive system both native and essential to that body. From that perspective, it seemed possible that the success of one man could really alter history, or even end it.

This selective forgetting is a basic feature of human psychology: We get used to new things, take them for granted, and the mind moves on to other problems. Since we are only ever capable of experiencing the present, memories of the past often deceive. Gratitude is fleeting.

The same phenomenon can be scaled up to the level of society. With all of the focus on history in contemporary discussions of racism, Americans seem to be unable (or unwilling) to imagine what the country was actually like before the civil rights movement. Those who lived through that era are remembered either as victims, as perpetrators, or as indifferent bystanders instead of as complex human beings living their lives under different conditions. The real tragedy of racism was its everyday banality. By religiously dramatizing our racial history, we risk losing vital historical perspective. If history is the memory of the human race, it is a selective memory indeed, and our selective memory on race explains how the perception of racism can grow even as racism itself is in precipitous decline.

No metric better indicates declining racial stigma in an increasingly multi-ethnic society than intermarriage. Between 1958 and 2013, the percentage of Americans who endorse intermarriage increased from four percent to 87 percent. Between 1980 and 2017, the rate of intermarriage nearly quadrupled from five percent to 18 percent, Pew Research found. The intermarriage rate is higher among American whites, Hispanics, and Asians than among black Americans, but there were other signs of symbolic and material progress for native blacks in the 2000s and 2010s. From 2001 to 2017 the incarceration rate of black Americans dropped by 34 percent, black life expectancy increased by about three years, and the percentage of blacks with bachelor’s degrees increased by 82 percent. Over the same period, there was a substantial increase in the number of black politicians and Academy Award winners. During the 2000s, hip-hop was in its golden age, Dave Chappelle’s show on comedy central was one of the most popular of all time, and there was no shortage of black A-list actors like Will Smith and Denzel Washington. Black Americans have been represented in a positive light in popular culture for a while now.

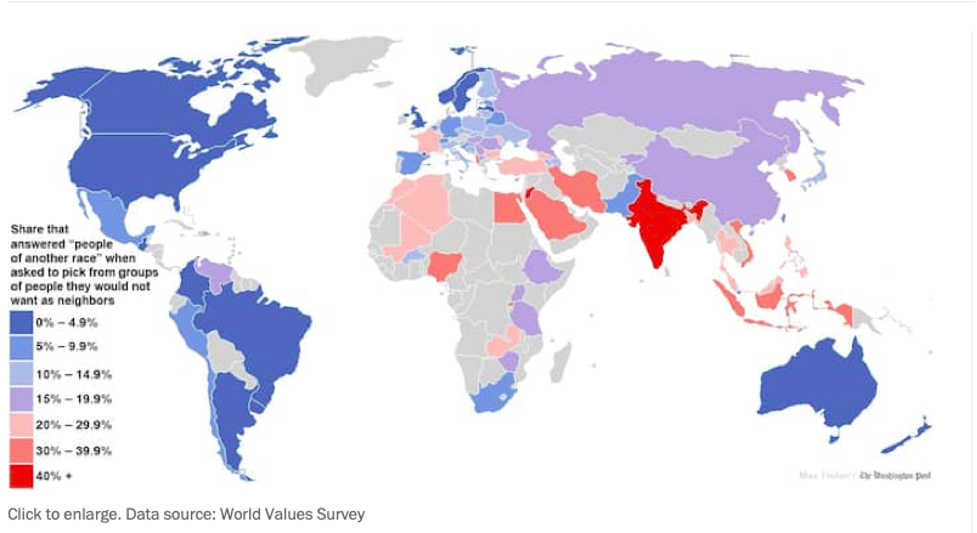

Whether or not people intuit these changes, meaningful progress was occurring right before we began to believe it wasn’t. In the 1970s, almost 60 percent of white Americans agreed with the statement “blacks shouldn’t push themselves where they’re not wanted,” the General Social Survey reported by Kaufmann found. This had declined to 20 percent by the early 2000s before the question was discontinued. According to a study by Swedish economists and a collection of world survey data published in the Washington Post, the United States is now among the least racist countries in the world in terms of who citizens accept as neighbors. For all intents and purposes, basic racial equality has long been achieved in the United States, even while the lofty aim of proportional outcomes between racial groups remains out of reach. If this isn’t progress, nothing is.

Nevertheless, many are reluctant to acknowledge the scope of racial progress in the United States—it smacks of self-congratulation and risks a denial of racism’s persistence. The title of an article from last year by the conservative writer David French counselled against complacency: “American Racism: We’ve Got So Very Far to Go.” A similar sentiment was expressed in a quote from a racial reconciliation worker in the New York Times: “You are talking about a 350-year problem that’s only a little more than 50 years toward correction.”

But if we don’t acknowledge how far we’ve come then we don’t know where we are and we can’t know where we are going. Is it really necessary to wait another 300 years before admitting that things have fundamentally changed in American culture and politics with respect to race? And what could “dismantling white supremacy” possibly mean in a country where the upcoming generation is predominantly “non-white,” or where a non-white racial group—Asian-Americans—vastly outearn white Americans, or where multiple African immigrant groups already eclipse the national average income, or where millions of minorities voted for a Trump-led Republican Party in 2020? Something is amiss when every major institution—from Walmart and Goldman Sachs to CNN and the CDC— supports a movement which holds that racism infects every major institution.

All of which gets to the central contradiction of modern anti-racist activism—its very success disproves its central claims. If white racism continues to dominate American society, it would be difficult to explain why some of the most powerful people on Earth were literally kneeling in homage to George Floyd. Ta-Nehisi Coates insists that the country will never consider the case for reparations because “it simply broke too much of America’s sense of its own identity.” And yet, programs described with that very term are being doled out at this very moment and Affirmative Action policies have existed for over 50 years. It is as if the Great Society and the War on Poverty never happened.

Which leaves a deeper question: Why would anybody want to deny racial progress? Besides the worry that complacency will interfere with the progressive focus on building a better future, resistance has become an end in itself. Coates exemplifies this attitude, “I too would gather my words and scream into the roaring waves, because to scream was to defy the story, and that defiance had meaning, no matter that the waves kept coming, would come, maybe, forever.”

If racism were to disappear tomorrow, not only would many activists, politicians, and pundits be out of a job, but many more Americans would lose a deeply felt sense of moral meaning. Committing oneself to an intergenerational struggle against the transhistorical force of white supremacy is one way of achieving a sense of purpose. The term “woke” itself implies an awakening. As Coates describes his own shift, “it became clear to me that the common theory of providential progress, of the inevitable reconciliation between the sin of slavery and the democratic ideal, was myth. Marking the moment of awakening is like marking the moment one fell in love.”

But if anti-racism is the new religion for secular people, as John McWhorter argues in his forthcoming book, isn’t it a relatively benign one? What’s wrong with grounding one’s spiritual identity in a tangible cause? After all, since racism is still a problem, is it so bad that a sense of mystery, wonder, and absolution emerge from the impulse to fight what’s left of it? My response to this, simply, is that religion is not politics. The effectiveness of policy on real world outcomes is either beside the point of, or completely antithetical to, what fulfills the essential human need to be part of something bigger than themselves. It is this subtle leap from the material to the symbolic that explains the belief that what’s happening in the consciences of white people is the cause of black poverty.

The sign of a truly meaningful protest is the acknowledgement of conditions under which protest would cease to be necessary. But a clear condition for the end of anti-racist activism no longer exists in America since the end of Jim Crow. If that condition is a world without any disparities between racial groups in a multiracial society, without any cosmic injustices or unfairness of any kind, then all that’s left is an endless quest for spiritual salvation in the guise of progressive politics.

There is nothing wrong with elevating anti-racism in one’s own life. But there is something wrong with imposing one’s moral reality upon total strangers. What works for us doesn’t necessarily work for other people. The point of representative democracy in a diverse society is to balance conflicting interests without devolving into ethnic tribalism. Moral zealotry—the absolute certainty of one’s own personal sense of good and evil—cannot be reconciled with the complex system of trade-offs involved in societal decision-making. Any moral theory is necessarily black and white. But reality, to paraphrase Albert Murray, is the color of infinity.

Progress is not inevitable, and the false belief that race relations are worsening risks becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. Social movements can worsen the conditions they seek to ameliorate by framing an improving issue as an ongoing crisis that justifies extreme and untested policy remedies. During the de-incarceration push of the early 1960s, for example, the idea took hold that criminal justice issues were going to worsen until society changed its unforgiving attitude towards criminal offenders and sought out root cause explanations.1 Meanwhile, the number of murders in 1960 was lower than it had been in 1950, 1940, and 1930, even though the population was growing substantially over those decades.2 After a series of landmark Supreme Court decisions expanding criminal rights, such as Mapp v. Ohio (1961) and Escobedo v. Illinois (1964), the crime rate skyrocketed. The murder rate in 1974 was nearly twice as high as in 1961, and the average citizen’s chances of becoming a victim of a major violent crime tripled between 1960 and 1976,3 sowing the seeds of the War on Drugs, the War on Crime, and, ultimately, mass incarceration.

Likewise, the War on Poverty was first conceived under the Kennedy Administration, not simply to fight poverty, but to fight welfare dependency.4 In fact, the number of people who lived below the official poverty line had shrunk considerably between 1950 and 19605 and declined by about a third between 1950 and 1965.6 After the Opportunity Act was passed in 1964, however, there was a spike in welfare dependency. The number of people receiving public assistance more than doubled from 1960 to 1977,7 leading to crude stereotypes about the poor and conservative pushback against safety nets. Moreover, black Americans experienced the largest rise out of poverty prior to the civil rights movement8 and well before President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society initiative that was designed to “eliminate poverty and racial injustice.” The expansion of welfare and the ghetto riots of the late ‘60s were followed by rises in poverty, single parenthood, crime, and community breakdown in inner cities across the country that would characterize the 1980s Baltimore neighborhood in which Ta-Nehisi Coates grew up—conditions he would use to agitate for the sorts of policies that arguably exacerbated them.

Whether or not America’s current racial upheaval will yield a major backlash remains to be seen. But if history is any indication, the sincere desire to overcome the injustices of history can misfire if left unchecked by the equally sincere desire to appreciate the incremental progress that made the present possible. Otherwise, the need to untether ourselves from history can have the effect of untethering ourselves from reality, with dire consequences that will continue well into the future.

References

1 Thomas Sowell, The Vision Of The Anointed, pg. 21

2 US Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, pg. 4143 Ibid. pg. 415

4 “Public Welfare Program—Message From The President of the United States (H. Doc. No. 325)” Congressional Record, February 1st, 1962, p. 1405

5 Charles Murray, Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950–1960, pg. 57

6 Ibid, pg. 64–65

7 James T. Patterson, America’s Struggle Against Poverty, p. 132

8 Thomas Sowell, Intellectuals And Race, pg. 127

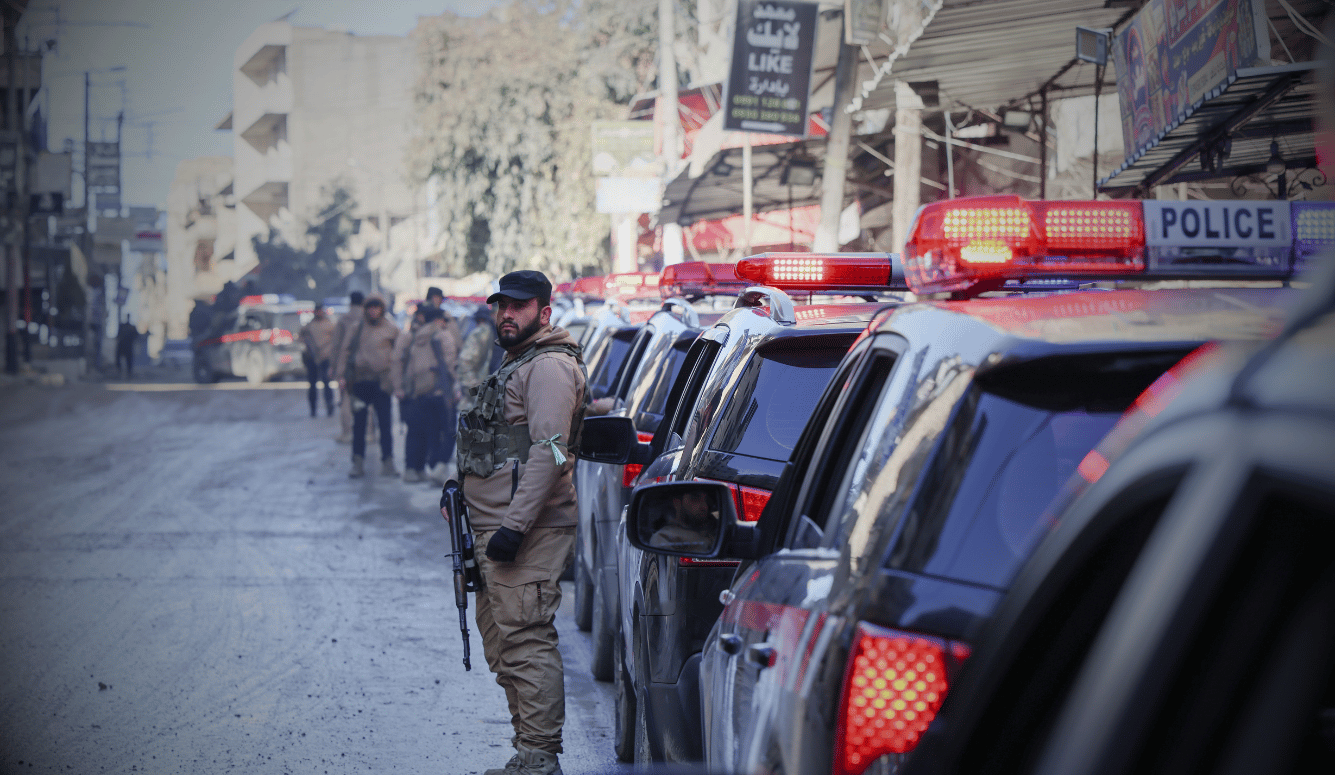

Feature image: Hundreds of Black Lives Matter Supporters marched on the local police station before a sit-in protest in Brixton High Street which brought London streets to standstill, July 9, 2016. Nicola Ferrari/Alamy Live News