History

Stopped Cold: Remembering Russia's Catastrophic 1939 Campaign Against Finland

Many Finnish soldiers felt pity for their opponents, prodded into battle by merciless commissars.

While the Germans had been flexible on the fine print of their August 23rd, 1939 non-aggression pact with the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin had been meticulous with his own territorial claims. By insisting on Soviet predominance in Finland and the Baltic states, Stalin could not only recover Russia’s old Tsarist borders in the north-west but also acquire naval bases to project Soviet power further into the Baltic Sea, whence came numerous stores vital to the Nazi war effort, from Swedish iron ore and timber to Finnish nickel. Compounding the economic leverage Stalin enjoyed over his partner in Berlin—owing to Hitler’s need for Soviet oil, manganese, cotton, and grain, as well as rubber transshipments from Asia—Soviet domination of the Baltic, Stalin believed, would turn Nazi Germany into a virtual economic vassal of the USSR.

The one thing Stalin had not reckoned on was that any of these neighbors might object. Certainly he did not expect resistance from the Baltic states. As early as September 24th, 1939, three days before Warsaw surrendered to Germany, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov had advised the Estonian foreign minister, Karl Selter, to “yield to the wishes of the Soviet Union in order to avoid something worse.” Latvia was next in line. When Lithuania’s foreign minister, Juozas Urbšys, objected that Soviet occupation would “reduce Lithuania to a vassal state,” Stalin replied brutally, “You talk too much.”

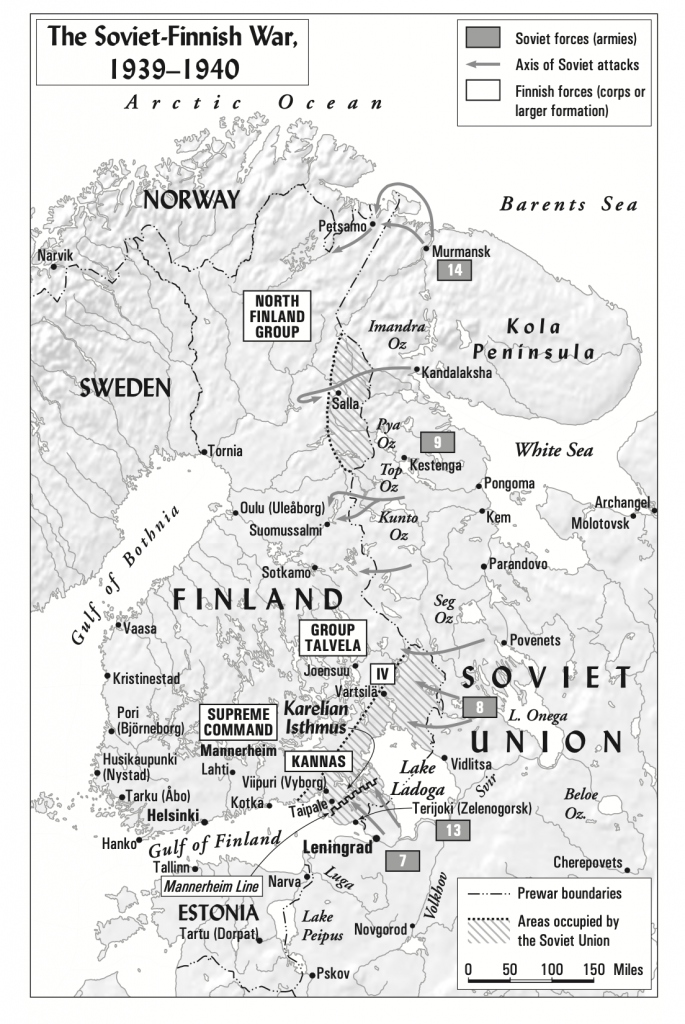

Finland had an even greater strategic importance for Russia. Its southern borders crept dangerously close to Leningrad (formerly Petrograd and Saint Petersburg), birthplace of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and Russia’s former capital. At one point, the frontier ran only 20 miles from the city outskirts across the flat plains of the Karelian Isthmus, a distance easily covered in hours by infantry, an hour by motorized divisions, or in mere minutes by warplanes. Finland’s southern coastline also dominated the Baltic Sea and Gulf of Finland approaches to Leningrad. (The Russian Imperial Navy had once placed its headquarters in the Finnish port of Helsinki, then Helsingborg.)

While Finland, with a tiny population of scarcely 3.5 million, could hardly have threatened the Soviet colossus, it had fought fiercely for independence during the Russian Civil War, conquering Helsinki in April 1918 and dealing the Reds a series of painful blows. The Finnish White Guards—as the Bolsheviks referred to the forces then commanded by the redoubtable Gustaf Mannerheim—had also, Stalin remembered, worked with German troops and collaborated with the British Baltic fleet. Had Mannerheim’s connections with the Germans not been so strong, the British might have lent his Finnish guards more support in the critical days of fall 1919, when Petrograd nearly fell to the Whites. But this was small consolation to Stalin, who mostly remembered the humiliation of losing Finland and Finnish double-dealing with outside powers. The fear that Finland might once again invite in a power hostile to the USSR, whether Britain or Germany, was never far from Stalin’s mind.

When Molotov summoned a Finnish delegation to the Kremlin on October 12th, 1939, Stalin made a personal appearance to heighten the intimidation factor, and he handed the Finns a brutal ultimatum demanding, among other things, “that the frontier between Russia and Finland in the Karelian Isthmus region be moved westward to a point only 20 miles east of Viipuri, and that all existing fortifications on the Karelian Isthmus be destroyed.” Stalin made it clear that this was the price that Finland had to pay to avoid the fate of Poland.

Aggressive and insulting as the Soviet demands on Finland were, Stalin and Molotov fully expected them to be accepted. As the Ukrainian party boss and future general secretary Nikita Khrushchev later recalled, the mood in the Politburo at the time was that “all we had to do was raise our voice a little bit and the Finns would obey. If that didn’t work, we could fire one shot and the Finns would put up their hands and surrender.” Stalin ruled, after all, a heavily armed empire of more than 170 million that had been in a state of near-constant mobilization since early September. The Red Army had already deployed 21,000 modern tanks, while the tiny Finnish Army did not possess an anti-tank gun. The Finnish Air Force had maybe a dozen fighter planes, facing a Red Air armada of 15,000, with 10,362 brand-new warplanes built in 1939 alone. Finnish Army reserves still mostly drilled with wooden rifles dating to the 19th century. By contrast, the Red Army was, in late 1939, the largest in the world, the most mechanized, the most heavily armored, and the most lavishly armed, even if surely not—because of Stalin’s purges—the best led.

One can imagine, therefore, Stalin’s shock when the Finns said no. Stunned by this unexpected resistance, Stalin and Molotov did not, at first, know quite what to do. With his highly placed spies in London, Stalin must have known that the mood in foreign capitals was becoming agitated by Soviet moves in the Baltic region. On October 31st, 1939, the British war cabinet took up the question of “Soviet Aggression Against Finland or Other Scandinavian Countries.” And earlier in the month, FDR had written to Moscow, demanding clarification of the Soviet posture on Finland. At this point, the Finnish cause seemed to have the potential to transform the so-far desultory and hypocritical British-French resistance to Hitler alone into a principled war against armed aggression by both totalitarian regimes.

On November 3rd, after yet another encounter in the Kremlin had gone sour with the Finns, Molotov warned the delegates that “we civilians can’t seem to do any more. Now it seems to be up to the soldiers. Now it is their turn to speak.” However, the truth was that, in November 1939, neither side was ready to wage war. Having expected the Finns to come around, Stalin had issued no orders to begin invasion preparations until after talks had finally broken down. The daunting task of preparing what was now a winter campaign fell to Kirill Meretskov, commander of the Leningrad military district. Meretskov did his best, but time was short and it was not easy to bring units up to combat strength on short notice.

The most critical task would be undertaken by the strongly mechanized Seventh and Thirteenth Armies, composed of nine rifle divisions, four tank brigades, and several heavy artillery regiments. These would advance across the Karelian Isthmus to try to break through the Mannerheim Line, a series of reinforced-concrete pillboxes, log-roofed bunkers, and earthworks guarded by Finland’s best troops. Meanwhile, the Eighth Army—with five rifle divisions, a light tank brigade, and several more heavy artillery regiments—would advance north-west from north of Lake Ladoga against a second, slightly less imposing Mannerheim defensive line. Further north, the Ninth Army, spearheaded by the mechanized 163rd Division, would advance westward into central Finland toward Suomussalmi, with the goal of cutting the country in two. Finally, the much smaller Fourteenth Army was to coordinate an attack with the Soviet northern fleet on Petsamo, on Finland’s northern tip, to secure the city’s critical nickel supplies and establish an Arctic perimeter against possible British naval encroachment.

On paper at least, Meretskov was able to throw over a million—in practice, more like 600,000—troops into this four-pronged invasion of Finland, along with thousands of warplanes that could offer close infantry support and bomb Finland’s cities. The overmatched Gustaf Mannerheim, recalled to command the Finnish defense, would have less than 150,000 troops to oppose this armored Soviet invasion, and many of his soldiers were older reservists and teenagers.

But wars are not won on paper. As Meretskov wrote on the eve of hostilities in late November 1939, “The terrain of coming operations is split by lakes, rivers, swamps, and is almost entirely covered by forests.” It was unsuitable terrain for motorized vehicles, and this would likely neutralize the effectiveness of Meretskov’s tanks and heavy armor, if not render them useless. “It is criminal to believe,” he concluded his report, with a note of realism, “that our task will be easy, or only like a march, as it has been told to me by officers in connection with my inspection.”

One of the biggest problems facing Meretskov was how to motivate Red Army grunts—training in the cold, snowy wastes of Karelia—to fight what was plainly just a war of aggression, in winter, no less. This was the job of PURKKA, the Red Army’s political department, headed by another of Stalin’s hatchet men, the former editor of Pravda Lev Mekhlis. Mekhlis had overseen the agitprop side of the Red Army purges in 1937–1938. By November 1939, Mekhlis ruled over a vast propaganda army inside the army, subjecting soldiers to several hours of ideological indoctrination every day by politruks (political commissars), during which the men were not training with firearms or practicing combat maneuvers. On November 23rd, Mekhlis reported to Stalin that “7th Army is not yet politically oriented enough.” To remedy the lack of war enthusiasm, Mekhlis promised to “mass-print” a new daily newspaper for Seventh Army. Mekhlis also created an occupation daily called The Voice of the Finnish People and hired translators to churn out Finnish editions of Pravda. Mekhlis dispatched another trusted Stalin workhorse, the Leningrad party boss and NKVD chieftain Andrei Zhdanov—who had signed hundreds of execution lists during the Great Terror—to indoctrinate the Soviet Ninth Army before it invaded central Finland.

At the center of the Soviet agitprop scheme for the Finnish invasion was a plan—cooked up by Mekhlis, Molotov, and Stalin—to erect a Finnish Communist puppet government just over the border in Terijoki, 30 miles north-west of Leningrad (today’s Russian Zelenogorsk). The idea was that this new “Democratic Government of Finland,” headed by the 58-year-old Finnish politician Otto Kuusinen (a Stalin stooge and resident of Moscow since 1920), would invite in the Red Army in order to, as Molotov’s communiqué put it, “establish good relations between our countries.” Kuusinen’s program for communizing Finland was dated, calling for an eight-hour workday—something Finnish workers had enjoyed for their country’s entire two-decade existence—along with the breaking up of the great landowner estates from Tsarist times, of which there were now very few left. More to the point, Kuusinen’s propaganda leaflets advised Finns not to shoot at the invading Russian army, but instead at “the White Guard government of [Väinö] Tanner and Mannerheim!” (Tanner hadn’t been Finland’s prime minister since 1927.)

Other than the transparent ruse of Kuusinen’s puppet government, the Soviet invasion of Finland followed the Nazi template from Poland closely. On November 26th, 1939, a border incident was arranged. Red Army gunners fired shells at the Mainila border outpost on the Karelian Isthmus, or the Finns fired shells at the Soviet border garrison, as Molotov claimed in his “protest” filed with the Finnish government—believed by no one outside, or indeed inside, the Kremlin. (It was later confirmed by neutral observers that the Finns did not even have artillery at Mainila.) Molotov demanded that the Finns withdraw all of their armed forces 25 kilometers behind the border with the USSR, a demand Mannerheim refused. With Stalin’s wafer-thin casus belli arranged, the Soviet invasion could proceed. In another homage to Hitler’s methods, there was no declaration of war.

Just past dawn on November 30th, Stalin’s undeclared war against Finland began with a furious artillery barrage on all fronts, followed by the scream of warplanes overhead. The only difference between the bald acts of territorial aggression in Finland and Poland was that the Soviet blitzkrieg was less efficient. Soviet medium bombers—mostly SB-2s cautiously dropping one-ton payloads from heights of 3,000 feet or more—weren’t especially accurate. In Helsinki, Russian bombers failed to knock out a single docking bay, airfield runway, Finnish warplane, or oil tank (although one airport hangar was destroyed). A stray bomb hit the Soviet legation building. According to eyewitnesses, Red fighter pilots strafed Helsinki suburbs as well, “machine-gunning women and children who had fled their houses to the fields.” Similar scenes of horror were repeated in Viipuri (Vyborg), as well as in provincial towns such as Lahti, Enso, and Kotka.

Meretskov’s landward assault on the Karelian Isthmus fared poorly. During the interval between the border incident of November 26th and the Russian onslaught early on November 30th, Mannerheim had wisely evacuated most of the civilian population. A series of clever booby traps were set for the invaders, including “pipe mines”—steel tubes crammed with explosives buried in snowdrifts and set off by hidden trip wires. The most effective defense of all was the Molotov cocktail, first used in Spain but ingeniously updated by the Finns, who would fill liquor bottles with a blend of gasoline or kerosene, tar, and potassium chloride. In fits of derring-do, Finnish soldiers on skis would drop these into the turrets of advancing tanks, ram branches or crowbars into the tank treads, or slice holes in the ice to sink them. Despite boasts in the Russian high command that the campaign would be over in 12 days, by mid-December, most of the Soviet Seventh and Thirteenth Armies were still blundering along short of the Mannerheim Line. On December 17th, in fact, the Thirteenth Army actually went into reverse, retreating after bloody losses in a clash at Taipale. By then, even the tiny Finnish Air Force of old Dutch Fokker fighters had joined the rout, knocking down Soviet bombers—one Finnish ace took out six in four minutes—and doing wonders for the morale of the Finns below. Further north, the Soviet Ninth Army was nearly destroyed in a battle near a burned-out Suomussalmi on December 9th. One Finnish ski sniper, a farmer named Simo Häyhä, personally killed, according to (improbable) legend, more than 500 Russians. Wounded Russians overwhelmed the hospitals of Leningrad. One overworked Soviet surgeon complained in early December that he was dealing with nearly 400 wounded Red Army soldiers every day.

In a sign of growing alarm in the Soviet high command, Mekhlis suspended even carefully edited press reports from the front on December 5th. A week later, purplish accounts in Pravda about Kuusinen’s puppet Terijoki government—6,000 Finnish proletarians allegedly had volunteered to fight in his “Finnish National Army”—were abandoned as too ludicrous for even devoted Communists to believe. Mekhlis and Zhdanov informed Stalin on December 19th that all advancing units had sustained “heavy losses” and that the men would need “rest time”—though all they were willing to grant was two days’ leave, barely enough time to get to Leningrad and back. By early January 1940, morale was so atrocious, with Russian soldiers deserting in droves, that Mekhlis’s PURKKA agitprop commissars abandoned euphemism and began reporting the truth.

So abysmal was the Red Army’s performance that Stalin felt the need to intervene. The most important change came in January 1940, with the arrival of NKVD battalions, called kontrolno-zagraditel’nyie otryadyi (control detachments), inside each Red Army unit, with powers of life and death over the soldiery. The creation of these punitive battalions, made public on January 24th in order to terrorize Red Army soldiers into compliance, ultimately stiffened (or at least stopped the bleeding away of) Soviet fighting morale in Finland. In the short run, though, the practice had the unfortunate effect of exacerbating the already frightful reputation of Stalin’s regime abroad. “At one place,” a Swedish volunteer told a British journalist, “the Russian soldiers were being driven forward like cattle with machine guns behind them, and they were stumbling forward hiding their faces with their arms and the Finns just mowed them down with machine guns. He said that the Finnish machine gunners were half of them in tears at having to do it; but what could you do. You couldn’t just let thousands of Russians [invade] the country.”

Many Finnish soldiers felt pity for their opponents, prodded into battle by merciless commissars. “The Russians,” one Finn noted, “have no nurses, no doctors, and no Red Cross equipment… They pour petroleum over their dead (and probably over a great many wounded, too) and burn them.” Another Finnish soldier told a British interviewer that “it is like killing helpless children to fire on these poor Russians who are forced to fight, who are so hungry and in cold clothing. One of the prisoners said when our soldiers gave him food ‘what a pity I did not take my wife with me so that she could also have some of this lovely food.’ What shall we do with all our prisoners, they need such a lot of food? Shall we wash them and clothe them and send them to America?”

Perhaps the most damning verdict on Soviet morale came from an anecdote, widely repeated around Helsinki, in which “three Russians, taken prisoner, ask for a last meal before they are shot. The Finns say: We’re not going to shoot you. So two of the prisoners said, ‘Well at least you are going to shoot this one’ pointing to the third, ‘he’s a commissar [i.e., a politruk].’ When the Finns said no, they said, ‘Well for heaven’s sake let us shoot him then.’”

Adapted from Stalin’s War by Sean McMeekin. Copyright © 2021 by Sean McMeekin. Reprinted by permission of Basic Books, New York, NY. All rights reserved.