Decolonize the Curriculum

How Will Decolonizing the Curriculum Help the Poor and Dispossessed?

The path to progress is definitely not paved by destroying the epistemological framework bequeathed to us by the Enlightenment.

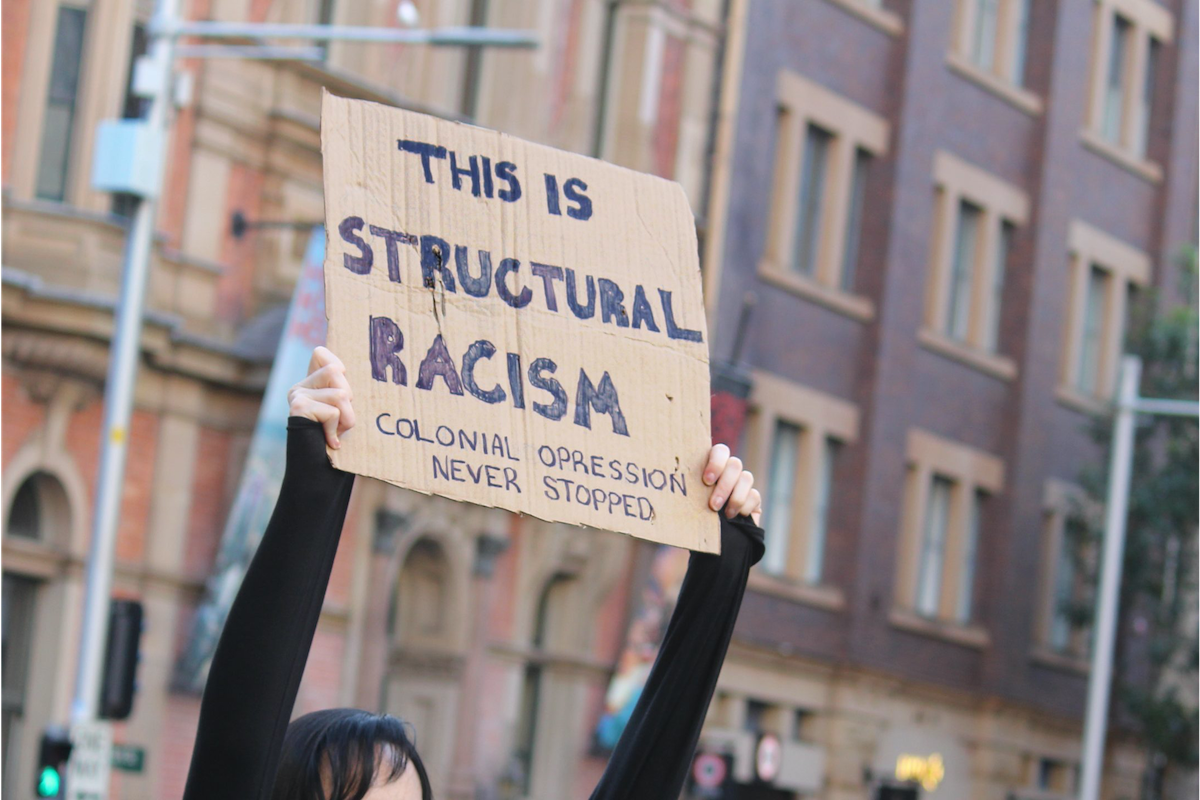

On February 8th, 2021, the Students of Color Liberation Front at the University of Michigan made a series of anti-racist demands, including a call to “Decolonize the University of Michigan’s pedagogies and campus broadly.” This is a recent manifestation of the “decolonize the university” movement, which has been making similar demands over the past few years at most Western academic institutions. The movement has called for universities to decolonize curricula and math, to privilege “other ways of knowing,” and to #DisruptTexts from the Western canon, among other demands. The Rhodes Must Fall in Oxford (RMFO) campaign explains that decolonization aims to “remedy the highly selective narrative of traditional academia—which frames the West as sole producers of universal knowledge—by integrating subjugated and local epistemologies” thereby creating “a more intellectually rigorous, complete academy.”

Demands for decolonized epistemology stem from legitimate grievances about colonial era atrocities. Some activists propose helpful suggestions for improving access to higher education for students in the global South, especially in STEM fields. For example, in Decolonise the University (2018), Pat Lockley promotes open access resources, including courses, publishing, data, lab, scholarship programs, and research exchanges. In the same volume, William Jamal Richardson makes an excellent case for an increased focus on “undone science”—areas of research “identified by social movements and other civil society organizations as having potentially broad social benefit.”

However, everyone should be deeply concerned about the serious damage to knowledge advancement that will occur if activists accomplish their goal to decolonize the epistemological foundation of science. During the 2016 #FeesMustFall protests at the University of Cape Town, a #ScienceMustFall activist explained her views on decolonizing science. A video was taken, which Emeritus Professor Tim Crowe analyzed in detail. The activist “derided science as enshrined unshakable ‘truth’ developed and driven as ‘Western modality.’” Therefore, “the whole thing should be scratched off” and replaced with an Afrocentric science.

This is a total misrepresentation of science, which doesn’t assert unshakable truths, but provisional ones; and which doesn’t belong to the West, but to the world. Science is a method for inquiry—guided by intellectual humility, skepticism, careful observation, questioning, hypothesis formulation, prediction, and experimentation—that is open to everyone, that aims to advance knowledge and improve the lives of all. While indigenous epistemologies are certainly worthy of study, and valuable in their own right, such epistemologies should not be promoted as superior to, or as a replacement for, Enlightenment epistemologies. This is not least because Enlightenment thinkers—most notably the founder of modern science Francis Bacon—articulated the intellectual foundation for extremely rapid improvements in global living standards.

The intellectual genealogy of decolonization demands

Why has decolonization become an increasingly popular rallying cry for social justice activists? The framework for decolonization demands stems from Critical Theory, specifically postcolonial and postmodern feminist critiques of the Enlightenment. During the “Science Wars” of the 1990s, between scientific realists and postmodernists, Sandra Harding, Carolyn Merchant, and Evelyn Fox Keller condemned Francis Bacon for what they deemed misogynistic sexual metaphors. Although they could have critiqued Bacon’s writing and left it at that, these feminists went much further, arguing that misogyny is at the heart of modern science. In 1995, Alan Soble made a convincing case that postmodern feminist readings of Bacon are based on misquotations, passages taken out of context, projection, and scholarly uncharitability. I would add that these critiques are wholly contingent upon the technological advancements produced by applying the epistemology advocated for by thinkers like Bacon. Imagine the short-sightedness of encountering a metaphor you dislike in a 17th century philosophical treatise, then proclaiming that the entire epistemological basis of modern civilization is inherently flawed—all while typing on a computer powered by reliable electricity, in a stable country, where you’ve never gone hungry.

Students promoting the decolonize the university movement make some reasonable demands, among them the integration of more Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) authors in the curriculum and hiring more BIPOC faculty members. However, the activists also make a more radical demand: epistemology itself must be decolonized by becoming decentered from the European Enlightenment tradition. In the introduction to Decolonising the University, the editors call for completely restructuring the knowledge systems of Western universities because, within them, “colonial intellectuals developed theories of racism, popularised discourses that bolstered support for colonial endeavours and provided ethical and intellectual grounds for the dispossession, oppression and domination of colonised subjects” (p.5). The editors do not mention that many Western universities were founded several centuries before European colonization began, including the universities of Bologna (1088), Oxford (1096), Salamanca (1134), Paris (1257), and Cambridge (1209), to name a few.

Lest one observe that the colonial period has passed, the editors assert that Western universities continue to “reproduce and justify colonial hierarchies” (p.6). But is providing intellectual grounds for colonialism all that Western universities have done, even now? The Decolonising the University scholar-activists think so. Rosalba Icaza and Rolando Vázquez assert that “movements to decolonise the university are fighting the ‘arrogant ignorance’ that is produced by a system of knowledge that is Eurocentric.” Western epistemology, they argue, claims to have “universal validity, while remaining oblivious to the epistemic diversity of the world” (p.112).

Similarly, Dalia Gebrial attacks the Enlightenment for having “forged and reproduced modalities of colonial thinking,” and for “racialising” the “values of reason and objective knowledge pursuit as white and European” (pp.27-8). Gebrial takes issue with how “the Enlightenment is geographically mapped as a self-contained, European project, rather than constituted through and alongside imperialism and slavery.” Gebrial, however, is silent on the question of whether non-Western empires that engaged in imperialism and slavery (for example, Barbary enslavement of Europeans) also have inherently flawed epistemologies that require decolonization. Neither Gebrial, nor any of the other Decolonising the University authors, mention that an estimated 40.3 million people are enslaved now.

Moreover, the scholar-activists mention only one instance of non-Western colonialism: the “profound impact of Japanese imperialism and Japan’s history of fascism” (p.72). However, they do not call for the decolonization of Japanese epistemology and universities. The contributors are also silent about Chinese territorial expansion, which has affected East Asia for the past four thousand years; the volume does not call for the decolonization of Chinese epistemology. Nor do they state that universities in the many regions colonized by the Ottoman Empire must be decolonized. And these are just a few examples of a much longer list of non-Western regions that have engaged in colonialism.

While some Western thinkers within universities did indeed justify colonialism, the implication that all Western universities, and their epistemological foundations, can be characterized as colonial enablers of dispossession, oppression, and domination, is a radical oversimplification.

Moreover, the assertion that the epistemology of Western universities is entirely a product of Western hegemony is an insult to every non-Western person who has contributed to knowledge production within Western universities. Decolonization activists demonize the Enlightenment, creating straw man arguments, which they propose to solve with “decolonial epistemology.” But what is decolonial epistemology? Although scholar-activists make a variety of recommendations, they all share similarities. I will address one proposal as a representative sample.

Decolonial epistemology and a recuperation of Francis Bacon

Decolonial activists, in their understandable anger over Western colonial injustices—provoked by Critical Theorist scholar-activists—are unlikely to read Francis Bacon. He can be dismissed as “pale, male (and often stale),” per the Decolonising the University’s editors’ formulation. Yet, decolonization activists might be surprised to find that Bacon makes strong arguments for much of what they demand. In Decolonising the University, Icaza and Vázquez identify three aspects of decolonial epistemology: positionality, relationality, and transitionality. Epistemic practices of positionality reject Enlightenment epistemology, which they characterize as a “closed form” of expertise that presents itself as “ahistorical and universally valid.” By contrast, positionality, an “open” form of expertise, is a “humble” approach in which researchers make the “location of their knowledge an integral part of their doing” (p.119).

In The Great Instauration (1620), one of the most important works of the Enlightenment, Bacon identified humility as his most important virtue: “Wherein if I have made any progress, the way has been opened to me by no other means than the true and legitimate humiliation of the human spirit.” Operating from a position of radical skepticism, Bacon maintained that the information we gather from our senses is a positioned knowledge, unique to the individual observer and not universal: “the testimony and information of the senses bears always a relation to man and not to the universe, and it is altogether a great mistake to assert that our senses are the measure of things.”

Because of these sensory limitations, Bacon recommended a process that we now call the scientific method. This process, which is open to everyone, relies on experimenters publishing their methods so that others can identify errors and correct them. Bacon made it clear that any “phantoms”—a metaphor for unfalsifiable hypotheses—must be rejected:

In every new and rather delicate experiment, although to us it may appear sure and satisfactory, we yet publish the method we employed, that, by the discovery of every attendant circumstance, men may perceive the possibly latent and inherent errors, and be roused to proofs of a more certain and exact nature, if such there be. Lastly, we intersperse the whole with advice, doubts, and cautions, casting out and restraining, as it were, all phantoms by a sacred ceremony and exorcism.

In addition to his cautions about experiments, Bacon urged vigilance about the purpose of knowledge: “we would in general admonish all to consider the true ends of knowledge, and not to seek it for the gratifications of their minds, or for disputation, or that they may despise others, or for emolument, or fame, or power, or such low objeets, but for its intrinsic merit and the purposes of life, and that they would perfect and regulate it by charity.” Bacon’s rejection of self-gratification, hate, fame, and power might gain the approval of 21st century decolonization activists.

Icaza and Vázquez’s second epistemological change, “relationality,” dismisses Enlightenment pedagogy as “authoritarian” and “one-directional.” In contrast, their proposed relational approach “is one in which the diverse backgrounds and the geo-historical positioning of the different participants in the classroom are rendered valuable” (120). This description of Enlightenment epistemology and pedagogy as “authoritarian,” “one-directional,” and failing to value diverse participants is uncharitable, to say the least. Bacon was completely anti-authoritarian; his epistemology was an explicit rejection of the knowledge deemed authoritative at his time. As Bacon explained, “That wisdom which we have derived principally from the Greeks is but like the boyhood of knowledge.” His purpose was to “commence a total reconstruction of sciences, arts, and all human knowledge, raised upon the proper foundations.”

Rather than asserting his own authority or seeking to impose it on others in a one-directional manner, Bacon discussed how he depended on assistance from others to advance knowledge benefiting “the human race,” a phrase he used five times in the prefatory section alone. Bacon bemoaned his ignorance about knowledge advancement in different locations: “we are far from knowing all that in the matter of sciences and arts has in various ages and places been brought to light and published, much less all that has been by private persons secretly attempted and stirred.” Bacon highlighted how knowledge production is an open form of expertise that happens in diverse locations.

Icaza and Vázquez’s final proposed epistemological change, “transitionality,” rejects “the abstract position of knowledge” and enables “students to bridge the epistemic border between the classroom and society.” The “recognition of difference as enriching for teaching and learning” is connected to “knowledge that has been humbled” and “recognises its own limits” (120). Since transitionality is related to teaching, it is fortunate that Bacon explained his pedagogical philosophy:

And the same humility which I use in inventing I employ likewise in teaching. For I do not endeavor either by triumphs of confutation, or pleadings of antiquity, or assumption of authority, or even by the veil of obscurity, to invest these inventions of mine with any majesty; which might easily be done by one who sought to give luster to his own name rather than light to other men’s minds. I have not sought (I say) nor do I seek either to force or ensnare men’s judgments, but I lead them to things themselves and the concordances of things, that they may see for themselves what they have, what they can dispute, what they can add and contribute to the common stock.

Bacon did not articulate an abstract position of knowledge. Instead, he emphasized what decolonial activists call for: knowledge that humbly recognizes its own limits. Bacon urged his students to think for themselves and participate in knowledge production. His pedagogy valued other perspectives because he implored his students to dispute bad ideas and to contribute their own. Additionally, Bacon affirmed the relevance of knowledge beyond the classroom. He wrote that he sought the sciences “not arrogantly in the little cells of human wit, but with reverence in the greater world.”

What is to be done?

The path to progress is definitely not paved by destroying the epistemological framework bequeathed to us by the Enlightenment. Yet it is important to understand why many young people are more attracted to social justice-based decolonization demands than to Enlightenment era intellectual advancements. Social justice ideology appeals to young adults’ desire to establish their identity, independent from their parents, and an ideology that represents itself as subversive is compelling. Also, as young people become aware of injustices, they are understandably captivated by a movement that represents itself as the most righteous way to advocate for justice.

For these reasons, it is necessary to make Enlightenment ideas not merely palatable, but inspiring. Educators must respond to decolonization activists’ arguments, then explain why Enlightenment ideas are a better foundation for improving people’s lives all over the world. Philanthropists are needed to fund a movement that popularizes an informed understanding of Enlightenment era scientific and political advancements. This movement should use online platforms and its curricula should have students read influential Enlightenment thinkers, in their own words, not only misleading representations promulgated by Critical Theory scholar-activists, as they do now.

This movement should explain how Enlightenment ideas accelerated global knowledge advancement. It is important to center the voices of immigrants to Western countries who have been drawn to the West for its liberal values, and for the wealth generation and scientific advancements produced by Enlightenment epistemology. People should create video and written testimonies of immigrants discussing their experiences in their home countries—specifically the lack of Enlightenment principles—and why these principles are attractive because they have been shown to work.

It is also essential to underscore that demands for decolonization in Western universities are the product of affluence. What do you think that impoverished people in the global South care about more: decolonizing Western epistemology or increasing their prosperity? While indigenous people are probably proud of their epistemology, I would bet that the majority care more about meeting their material needs. Decolonization activists might consider how changing epistemology in Western universities will solve the main problems experienced by most people in the world, including extreme poverty, rampant political corruption, substandard infrastructure, inadequate police, and dysfunctional judicial systems. The political advancement of the Enlightenment, liberalism, provides a framework for solving these problems by establishing limited, republican government; enforcing the rule of law; and protecting individual rights and liberties, especially freedom of speech, so that people can have honest discussions about problems and work toward solutions—without descending into authoritarianism and violence.

People in the West must ensure that our educators teach the epistemology bequeathed to us by Enlightenment intellectuals so that we continue to advance and prosper. In the 17th century, Francis Bacon lamented people in his time who did little to improve knowledge, remarking that such people “made a passage for themselves and their own opinions by pulling down and demolishing former ones; and yet all their stir has but little advanced the matter, since their aim has been not to extend philosophy and the arts in substance and value, but only to change doctrines and transfer the kingdom of opinions to themselves.” This strikes me as the most precise description of decolonial activists that I have seen. Be forewarned: decolonization demands won’t stop at the university gates. As Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang state, decolonization is not a metaphor; it is a struggle over dispossession, the repatriation of indigenous land, and the seizing of imperial wealth. If you have any European heritage, the activists will soon demand that you be decolonized, too.