Art

With Theatres Shuttered, I Tried to Stage a 'Zoom Play.' (It Didn't Work)

I once directed a classical musical—Anything Goes—at Canada’s Shaw Festival. But that’s the only play I’ve directed that was seen by a large audience.

I have always been a playwright. When my grade-six teacher told us to compose our imaginary life stories, mine was called Autobiography of a Playwright. Even back then, I was writing skits and persuading the neighbourhood kids to perform in them. My inspiration (and this will tell you something about my age) was Bing Crosby in Going My Way—a priest who cajoled local juvenile delinquents into singing for the church choir. When I was eight or nine years old, I told my mother I was depressed. “I don’t have anything to look forward to,” I said. She suggested that my father set up a little stage in the basement—complete with a curtain. I was in heaven.

As a young man, unfortunately, I watched the cinematic representations of stereotypical playwright characters morph from respected geniuses to laughable neurotics. In the 1950 drama All About Eve, playwright Lloyd Richards was portrayed as a typical pipe-smoking intellectual of the 1940s. Richards casually name-drops “Miller” and “Sherwood” (Arthur and Robert, respectively), situating himself in the context of the day’s serious writers—members of the gate-keeping cultural elite. When spoiled actress Margo Channing (Bette Davis) gets too big for her britches, Richards admonishes her: “There comes a time that a piano realizes that it has not written a concerto.”

By 1967, on the other hand, Mel Brooks was giving us Franz Liebkind in The Producers—a mad Nazi playwright who—when he’s not talking to the birds on his roof, is writing his masterpiece, Springtime for Hitler. Fifteen years later, in the 1982 comedy Tootsie, Bill Murray plays Jeff Slater, a self-absorbed, narcissistic playwright who swills beer at an opening night party while his devoted followers remain hypnotized by his pretentious musings. “I did a thing called Suicides of the American Indian—and nobody showed, nobody came,” he laments.

In part, this transformation can be traced to the general downgrading of trust and status enjoyed by elite institutions that played out in many areas of society following the rise of counterculture. But in the realm of theatre, the rise of the mega-musical helped the process along. The first specimen of the genre came in 1975 with A Chorus Line, which ran for 6,137 performances (a record that would last till Cats broke it in 1997). Commercially, the hit helped lift Broadway out of its 1970s-era tailspin. But artistically, the Great White Way has never recovered. And the decades that followed brought us the humourless Puccini pastiches of Andrew Lloyd Webber and then an array of Disney family musicals. Thanks to Garth Drabinsky, Canadian producer of Phantom of the Opera and numerous other blockbusters, the almighty dollar triumphed on Toronto stages as well.

However, the theatre is not dead yet, and it’s become my mission to help save it. I’m heartened by the realization that new technologies do not kill old ones. Some of my best friends still listen to radio. And Netflix hasn’t yet spelled the end of movie theatres (though COVID-19 has been doing its best to push many into bankruptcy). While we aren’t likely to see much live theatre in many cities until 2022, those venues that do survive may well see a surge in demand from the millions of locked down patrons hungry for traditionally communal forms of entertainment.

One trend that’s become popular under lockdown is the so-called “Zoom play”—a theatrical production transmitted to your phone and computer as, in effect, a mass-muted video conference call. However, I’ve never seen a Zoom production, for the simple reason that liveness is the essence of theatre. Any single performance of a play will (except in rare cases) never be seen again. The magic happens only once in that exact way. Thus, the audience is always a part of the play, even if they aren’t called upon to participate in it. If theatre didn’t offer this special experience, it would have died long ago.

Earlier on in the pandemic, I got so frustrated by the disappearance of live theatre that, at one point, I broke down and wrote my own Zoom play—a peppy one-act musical. I gathered a bunch of actors who had a great deal of enthusiasm (as actors always do), and I got myself a technical expert to help out with the various filters and background effects. Then we had two rehearsals, each of us acting from our own homes.

After then, frankly, I couldn’t go on.

The new technology bored me. I also found it difficult to direct actors through Zoom. I need to look into a person’s eyes at close quarters and get their vibe, to assure myself they are not secretly upset or artistically estranged. In Zoom rehearsals, if I’d ask actors how they were doing, they’d give me a cheery “fine!” But my paranoia took over. Were they, in fact, “fine”? Were they really?

There’s another more important reason why I abandoned the play: It was bad. On some level, I’d realized that if I was going to market my little musical online, it would necessarily have to be upbeat, not at all controversial. I’d be depending on promotion through social media, for a mass audience, much of which would be young and woke. The wan thing I came up with reflected that fact.

I once directed a classical musical—Anything Goes—at Canada’s Shaw Festival. But that’s the only play I’ve directed that was seen by a large audience. At the Toronto theatre I founded (and from which I am now very much departed), I mostly wrote plays for myself. My personal nightmare is boredom. Writing plays, books—and essays like this—is the way I keep myself from going mad. I believe many writers write for the same reason. The external result is both kudos and brickbats. At best, I’m accused of being brave. At worst, malicious. But in truth, I’m neither. I’m just trying to keep myself this side of crazy.

But it’s hard for an artist to fend off craziness when your most outspoken critics try to gaslight you as a bigot or, worse, a traitor to your own community. From the get-go, I’ve always been an identifiably gay playwright. In the early part of my career, when homophobia was more common, this fact made me controversial in and of itself. What now makes me controversial is the fact that I treat gayness as a given background element—which means that some of my gay characters are perfectly lovely, while others will be less so. This has gotten me into trouble. It’s one of the reasons (I’ll let my critics list the others) why my plays have almost always been performed in small venues.

On a recent Quillette podcast episode, editor Leon Wieseltier made the point that the best jazz clubs were always small—because this was the kind of music that had a small but devoted (and often influential) fan base. This kind of smallness may be just as important as liveness is in separating real theatre—the kind I love—from other media. Audience members simply can’t see an actor’s face properly if they’re too far away. And if they’re watching on Zoom, even the largest monitor in the world can’t bring them into a state of real artistic intimacy.

Another consequence of physical smallness is that you can get away with murder (which I mean in a good way)—no small benefit in an age of cancel culture. With Zoom plays, on the other hand, you’re always a single tweet away from being mobbed, since the easiest way to get something cancelled is to put it on the web. It’s the worst of both worlds, in fact: Small in budget and ambition, lacking in intimacy, but with all of the professional tripwires and inducements to self-censorship that attend bigger, blander productions.

The most expensive Broadway production in history was Spider-Man: Turn Off the Dark. With a budget of US$75 million, it arguably represented the most ambitious (and therefore grotesque) effort to turn live theatre into an ersatz Hollywood experience. What I’ve learned is that you don’t need a lot of cash to produce a play—just an empty space that actors and audience share. “I can take any empty space and call it a bare stage,” English theatre legend Peter Brook once said. “A man walks across this empty space whilst someone else is watching him, and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged.” As I can attest, even a curtained basement alcove will do nicely.

I was on a panel at the Toronto Fringe a few years ago, where I listened to young producers asking variations on the question, “How can I reach a wider audience?” It’s a natural question for someone young to ask, especially in an age when success is measured in follower counts, subscriptions, and, of course, money. I offered a note of dissent by asking, “Why would you want to?” It wasn’t a popular view, but I imagine that many of the people in the room will age into it.

Let me be clear that I’m no “size queen” when it comes to venue, and so won’t turn my nose up at a great piece of theatre that happens to play in big houses with a big cast and budget. But the essence of theatre (or any art form, in fact) is challenging the audience with a different point of view, not just giving them what they want (or think they want).

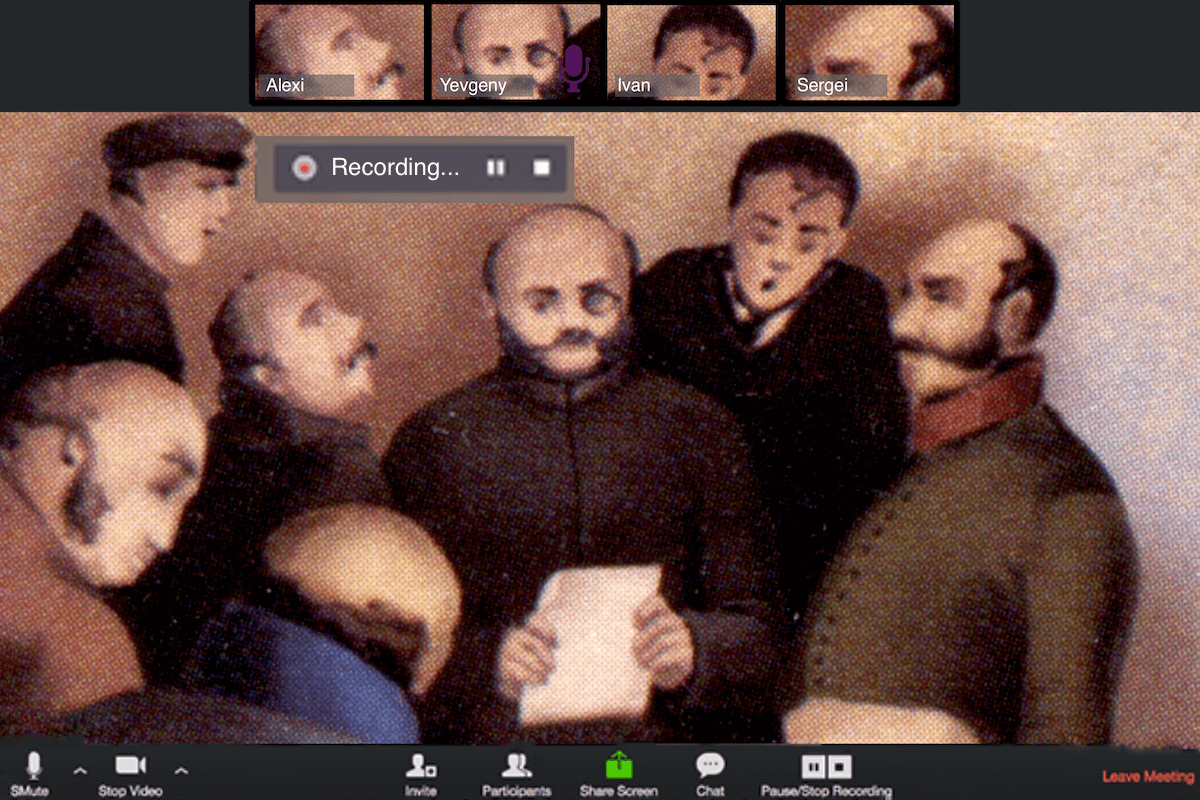

Shakespeare was very good at this. Near the end of her life, Queen Elizabeth famously asked for a command performance of Richard II—a play about a deposed monarch—having reportedly said, “I am Richard II; know ye not that?” Similarly, Czar Nicholas I of Russia turned up personally at the first 1836 production of Nicolay Gogol’s The Inspector-General, which lampooned the corruption, incompetence and backwardness of village life under Czarist rule. The ruler laughed and applauded merrily, remarking (it is said), “Everybody gets it, and I most of all.”

This was during an era of strict censorship in Russia. And the fact that the Czar had permitted the play to be performed—let alone that he attended in person, and received it warmly in front of other audience members—was a big deal. It shows how, under the right conditions, a play can be a revolutionary act. But it’s a kind of revolution that will not, indeed cannot, be televised.