Activism

Unspeakable Truths about Racial Inequality in America

We have to make ourselves equal. No one can do it for us.

This is the text of a lecture delivered by the author as part of the Benson Center Lecture Series at the University of Colorado, Boulder, on February 8th, 2021.

I am a black American intellectual living in an age of persistent racial inequality in my country. As a black man I feel compelled to represent the interests of “my people.” (But that reference is not unambiguous!) As an intellectual, I feel that I must seek out the truth and speak such truths as I am given to know. As an American, at this critical moment of “racial reckoning,” I feel that imperative all the more urgently. But, I ask, what are my responsibilities? Do they conflict with one another? I will explore this question tonight.

My conclusion: “My responsibilities as a black man, as an American, and as an intellectual are not in conflict.” I defend this position as best I can in what follows. I also try to illustrate the threat “cancel culture” poses to a rational discourse about racial inequality in America that our country now so desperately requires. Finally, I will try to model how an intellectual who truly loves “his people” should respond. I will do this by enunciating out loud what have increasingly become some unspeakable truths. So, brace yourselves!

I begin with a provocation: Consider this story from my hometown newspaper, the Chicago Sun-Times, that ran on May 31st, 2016. (Things have only gotten worse since.) I ask you to bear with me here because these details matter. We must look them squarely in the face:

Six people were killed, including a 15-year-old girl, and at least 63 others were wounded in shootings across Chicago over Memorial Day weekend.

The total number of people shot during the weekend this year surpassed the 2015 holiday, when 55 people were shot, 12 fatally, over Memorial Day weekend.

The most recent homicide happened late Monday in the Washington Park neighborhood on the South Side.

Officers responding to a call of shots fired about 11pm found James Taylor lying on the ground near his vehicle in the 5100 block of South Calumet, according to Chicago Police and the Cook County medical examiner’s office. Taylor, who lived in the 6500 block of South Ellis, had been shot in the chest and was pronounced dead at the scene, authorities said.

Witnesses at the scene were not cooperating with detectives.

About the same time, a man was shot to death in the West Rogers Park neighborhood on the North Side.

Officers responding to a call of shots fired about 11pm found 39-year-old Johan Jean lying in a gangway in the 6400 block of North Rockwell, authorities said.

Jean, who lived in the 100 block of North Ashland in Evanston, was shot in the neck and taken to Presence Saint Francis Hospital in Evanston, where he was later pronounced dead, authorities said. Police said he was 25 years old.

A source said the shooting stemmed from a dispute between two women. One of them has a child with the man and the other was his girlfriend. Both women were armed, and the man was eventually shot during the argument. No weapons were recovered from the scene.

About 5.20pm Saturday, a man was shot to death in the Fuller Park neighborhood on the South Side.

Garvin Whitmore, 27, was sitting in the driver seat of a vehicle with a passenger, 26-year-old Ashley Harrison, in the 200 block of West Root, when someone walked up to the vehicle and shot him in the head, according to police and the medical examiner’s office.

Whitmore, of the 5800 block of West 63rd Place, was pronounced dead at the scene at 5.29pm, authorities said.

All of the victims were black people. Sixty-three shot, six dead, one weekend, one city. Here’s the thing: reports such as this could be multiplied dozens of times, effortlessly. If a black intellectual truly believes that “Black Lives Matter,” then what is he supposed to say in response to such nauseating reports—that “there is nothing to see here?” I think not.

Violence on such a scale involving blacks as both perpetrators and victims poses a dilemma to someone like myself. On the one hand, as the Harvard legal scholar Randall Kennedy has observed, we elites need to represent the decent law-abiding majority of African Americans cowering fearfully inside their homes in the face of such violence. We must do so not just to enhance our group’s reputation as in the “politics of respectability” but mainly as a precondition for our own dignity and self-respect.

On the other hand, we elites must also counter the demonization of young black men which the larger American culture has for some time now been feverishly engaged in. Even as we condemn murderers, we cannot help but view with sympathy the plight of many poor youngsters who, though not incorrigible, have nevertheless committed crimes. We must wrestle with complex historical and contemporary causes internal and external to the black experience that help to account for this pathology. (There’s no way around it. This is pathology. The behavior in question here is not okay. That one can adduce social-psychological explanations does not resolve all moral questions.)

Where is the self-respecting black intellectual to take his stand? Must he simply act as a mouthpiece for movement propaganda aiming to counteract “white supremacy”? Has he anything to say to his own people about how some of us are living? Is there space in American public discourses for nuanced, subtle, sophisticated moral engagement with these questions? Or are they mere fodder for what amount to tendentious, cynical, and overtly politically partisan arguments on behalf of something called “racial equity”? And what about those so-called “white intellectuals”? Do they have to remain mute? Or, must they limit themselves to incanting anti-racist slogans?

I don’t know all of the answers here, but I know that those victims had names. I know they had families. I know they did not deserve their fate. I know that black intellectuals must bear witness to what actually is taking place in our midst; must wrestle with complex historical and contemporary causes both within and outside the black community that bear on these tragedies; must tell truths about what is happening and must not hide from the truth with platitudes, euphemisms and lies.

I know, despite whatever causal factors may be at play, that we black intellectuals must insist each youngster is capable of choosing a moral way of life. I know that, for the sake of the dignity and self-respect of my people as well as for the future of my country, we American intellectuals of all colors must never lose sight of what a moral way of life consists in. And yet, we are in imminent danger of doing precisely that, I fear. Here’s why.

The first unspeakable truth: Downplaying behavioral disparities by race is actually a “bluff”

Socially mediated behavioral issues lie at the root of today’s racial inequality problem. They are real and must be faced squarely if we are to grasp why racial disparities persist. This is a painful necessity. Activists on the Left of American politics claim that “white supremacy,” “implicit bias,” and old-fashioned “anti-black racism” are sufficient to account for black disadvantage. But this is a bluff that relies on “cancel culture” to be sustained. Those making such arguments are, in effect, daring you to disagree with them. They are threatening to “cancel” you if you do not accept their account: You must be a “racist”; you must believe something is intrinsically wrong with black people if you do not attribute pathological behavior among them to systemic injustice. You must think blacks are inferior, for how else could one explain the disparities? “Blaming the victim” is the offense they will convict you of, if you’re lucky.

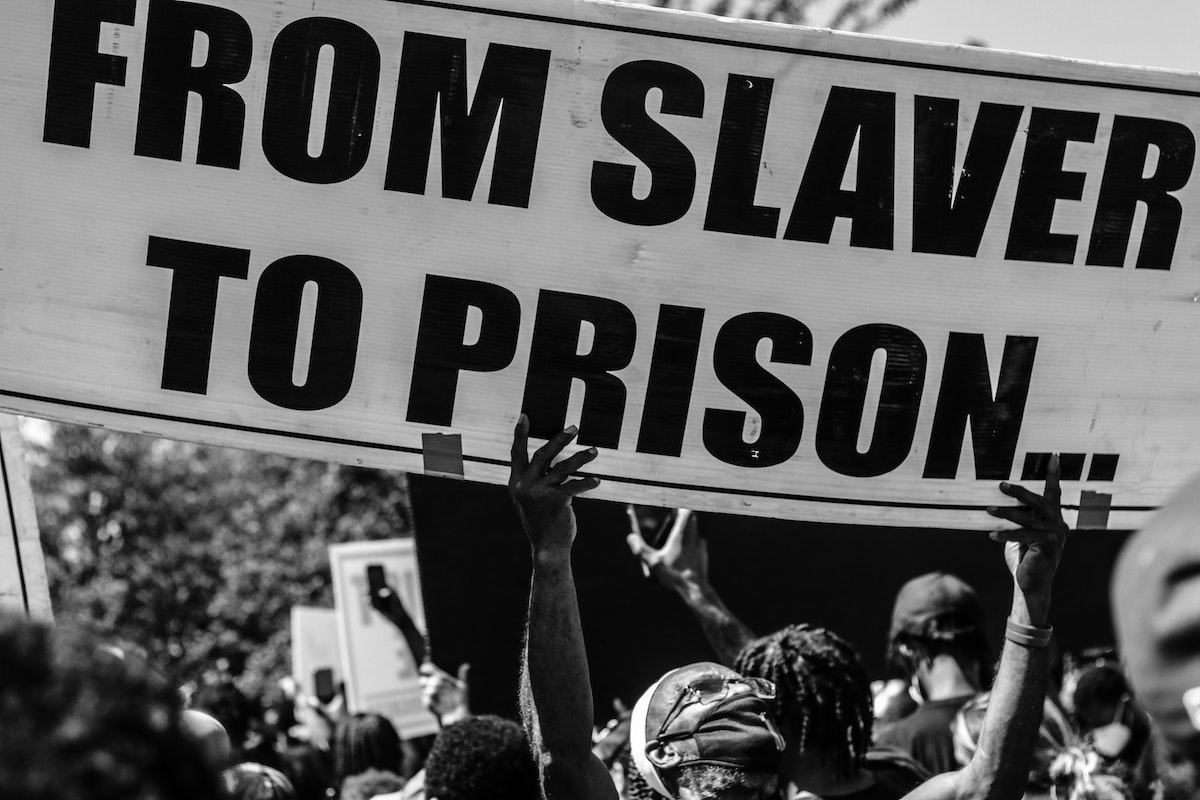

I claim this is a dare; a debater’s trick. Because, at the end of the day, what are those folks saying when they declare that “mass incarceration” is “racism”—that the high number of blacks in jails is, self-evidently, a sign of racial antipathy? To respond, “No. It’s mainly a sign of anti-social behavior by criminals who happen to be black,” one risks being dismissed as a moral reprobate. This is so, even if the speaker is black. Just ask Justice Clarence Thomas. Nobody wants to be cancelled.

But we should all want to stay in touch with reality. Common sense and much evidence suggest that, on the whole, people are not being arrested, convicted, and sentenced because of their race. Those in prison are, in the main, those who have broken the law—who have hurt others, or stolen things, or otherwise violated the basic behavioral norms which make civil society possible. Seeing prisons as a racist conspiracy to confine black people is an absurd proposition. No serious person could believe it. Not really. Indeed, it is self-evident that those taking lives on the streets of St. Louis, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Chicago are, to a man, behaving despicably. Moreover, those bearing the cost of such pathology, almost exclusively, are other blacks. An ideology that ascribes this violent behavior to racism is laughable. Of course, this is an unspeakable truth—but no writer or social critic, of whatever race, should be cancelled for saying so.

Or, consider the educational achievement gap. Anti-racism advocates, in effect, are daring you to notice that some groups send their children to elite colleges and universities in outsized numbers compared to other groups due to the fact that their academic preparation is magnitudes higher and better and finer. They are daring you to declare such excellence to be an admirable achievement. One isn’t born knowing these things. One acquires such intellectual mastery through effort. Why are some youngsters acquiring these skills and others not? That is a very deep and interesting question, one which I am quite prepared to entertain. But the simple retort, “racism”, is laughable—as if such disparities have nothing to do with behavior, with cultural patterns, with what peer groups value, with how people spend their time, with what they identify as being critical to their own self-respect. Anyone actually believing such nonsense is a fool, I maintain.

Asians are said, sardonically, according to the politically correct script, to be a “model minority.” Well, as a matter of fact, a pretty compelling case can be made that “culture” is critical to their success. Read Jennifer Lee and Min Zhou’s book, The Asian American Achievement Paradox. They have interviewed Asian families in Southern California, trying to learn how these kids get into Dartmouth and Columbia and Cornell with such high rates. They find that these families exhibit cultural patterns, embrace values, adopt practices, engage in behavior, and follow disciplines that orient them in such a way as to facilitate the achievements of their children. It defies common sense, as well as the evidence, to assert that they do not or, conversely, to assert that the paucity of African Americans performing near the top of the intellectual spectrum—I am talking here about academic excellence, and about the low relative numbers of blacks who exhibit it—has nothing to do with the behavior of black people; that this outcome is due to institutional forces alone. That, quite frankly, is an absurdity. No serious person could believe it.

Nor does anybody actually believe that 70 percent of African American babies being born to a woman without a husband is (1) a good thing or (2) due to anti-black racism. People say this, but they don’t believe it. They are bluffing—daring you to observe that the 21st-century failures of African Americans to take full advantage of the opportunities created by the 20th century’s revolution of civil rights are palpable and damning. These failures are being denied at every turn, and these denials are sustained by a threat to “cancel” dissenters for being “racists.” This position is simply not tenable. The end of Jim Crow segregation and the advent of the era of equal rights was transformative for blacks. And now—a half-century down the line—we still have these disparities. This is a shameful blight on our society, I agree. But the plain fact of the matter is that some considerable responsibility for this sorry state of affairs lies with black people ourselves. Dare we Americans acknowledge this?

Leftist critics tout the racial wealth gap. They act as if pointing to the absence of wealth in the African American community is, ipso facto, an indictment of the system—even as black Caribbean and African immigrants are starting businesses, penetrating the professions, presenting themselves at Ivy League institutions in outsize numbers, and so forth. In doing so, they behave like other immigrant groups in our nation’s past. Yes, they are immigrants, not natives. And yes, immigration can be positively selective. I acknowledge that. Still, something is dreadfully wrong when adverse patterns of behavior readily visible in the native-born black American population go without being adequately discussed—to the point that anybody daring to mention them risks being cancelled as a racist. This bluff can’t be sustained indefinitely. Despite the outcome of the recent election, I believe we are already beginning to see the collapse of this house of cards.

A second unspeakable truth: “Structural racism” isn’t an explanation, it’s an empty category

The invocation of “structural racism” in political argument is both a bluff and a bludgeon. It is a bluff in the sense that it offers an “explanation” that is not an explanation at all and, in effect, dares the listener to come back. So, for example, if someone says, “There are too many blacks in prison in the US and that’s due to structural racism,” what you’re being dared to say is, “No. Blacks are so many among criminals, and that’s why there are so many in prison. It’s their fault, not the system’s fault.” And it is a bludgeon in the sense that use of the phrase is mainly a rhetorical move. Users don’t even pretend to offer evidence-based arguments beyond citing the fact of the racial disparity itself. The “structural racism” argument seldom goes into cause and effect. Rather, it asserts shadowy causes that are never fully specified, let alone demonstrated. We are all just supposed to know that it’s the fault of something called “structural racism,” abetted by an environment of “white privilege,” furthered by an ideology of “white supremacy” that purportedly characterizes our society. It explains everything. Confronted with any racial disparity, the cause is, “structural racism.”

History, I would argue, is rather more complicated than such “just so” stories would suggest. These racial disparities have multiple interwoven and interacting causes, from culture to politics to economics, to historical accident to environmental influence and, yes, also to the nefarious doings of particular actors who may or may not be “racists,” as well as systems of law and policy that disadvantage some groups without having been so intended. I want to know what they are talking about when they say “structural racism.” In effect, use of the term expresses a disposition. It calls me to solidarity. It asks for my fealty, for my affirmation of a system of belief. It’s a very mischievous way of talking, especially in a university, although I can certainly understand why it might work well on Twitter.

Another unspeakable truth: We must put the police killings of black Americans into perspective

There are about 1,200 fatal shootings of people by the police in the US each year, according to the carefully documented database kept by the Washington Post which enumerates, as best it can determine, every single instance of a fatal police shooting. Roughly 300 of those killed are African Americans, about one-fourth, while blacks are about 13 percent of the population. So that’s an over-representation, though still far less than a majority of the people who are killed. More whites than blacks are killed by police in the country every year. You wouldn’t know that from the activists’ rhetoric.

Now, 1,200 may be too many. I am prepared to entertain that idea. I’d be happy to discuss the training of police, the recruitment of them, the rules of engagement that they have with citizens, the accountability that they should face in the event they overstep their authority. These are all legitimate questions. And there is a racial disparity although, as I have noted, there is also a disparity in blacks’ rate of participation in criminal activity that must be reckoned with as well. I am making no claims here, one way or the other, about the existence of discrimination against blacks in the police use of force. This is a debate about which evidence could be brought to bear. There may well be some racial discrimination in police use of force, especially non-lethal force.

But, in terms of police killings, we are talking about 300 victims per year who are black. Not all of them are unarmed innocents. Some are engaged in violent conflict with police officers that leads to them being killed. Some are instances like George Floyd—problematic in the extreme, without question—that deserve the scrutiny of concerned persons. Still, we need to bear in mind that this is a country of more than 300 million people with scores of concentrated urban areas where police interact with citizens. Tens of thousands of arrests occur daily in the United States. So, these events—which are extremely regrettable and often do not reflect well on the police—are, nevertheless, quite rare.

To put it in perspective, there are about 17,000 homicides in the United States every year, nearly half of which involve black perpetrators. The vast majority of those have other blacks as victims. For every black killed by the police, more than 25 other black people meet their end because of homicides committed by other blacks. This is not to ignore the significance of holding police accountable for how they exercise their power vis-à-vis citizens. It is merely to notice how very easy it is to overstate the significance and the extent of this phenomenon, precisely as the Black Lives Matter activists have done.

Thus, the narrative that something called “white supremacy” and “systemic racism” have put a metaphorical “knee on the neck” of black America is simply false. The idea that as a black person I dare not step from my door for fear that the police would round me up or gun me down or bludgeon me to death because of my race is simply ridiculous. That is like not going outdoors for fear of being struck by lightning. The tendentious interpretation of every one of these incidents where violent conflict emerges between police and an African American, such that the incident is read as if it were the latter-day instantiation of the lynching of Emmett Till—that posture, I am obliged to report, is simply preposterous. Fear of being “cancelled” is the only thing that keeps many white people outside of the alt-Right from saying so out loud. “White silence” about anti-racism is not “violence.” Nor is it tacit agreement. But it should worry us.

I also want to stress the dangers of seeing police killings primarily through a racial lens. These events are regrettable regardless of the race of the people involved. Invoking race—emphasizing that the officer is white, and the victim is black—tacitly presumes that the reason the officer acted as he did was because the dead young man was black, and we do not necessarily know that. Moreover, once we get into the habit of racializing these events, we may not be able to contain that racialization merely to instances of white police officers killing black citizens. We may find ourselves soon enough in a world where we talk about black criminals who kill unarmed white victims—a world no thoughtful person should welcome, since there are a great many such instances of black criminals harming white people. Framing them in racial terms is obviously counter-productive.

These are criminals harming people, who should be dealt with accordingly. They do not stand in for their race when they act badly. White victims of crimes committed by blacks oughtn’t to see themselves mainly in racial terms if their automobile is stolen, or if someone beats them up and takes their wallet or breaks into their home and abuses them. Such things are happening on a daily basis in this country. We shouldn’t want to live in a world where such events are interpreted primarily through a racial lens. People are playing with fire, I think, when they gratuitously bring that sensibility to police-citizen interaction. That will not be the end of the story.

Yet another unspeakable truth: There is a dark side to the “white fragility” blame game

Likewise, I suspect that what we are hearing from the progressives in the academy and the media is but one side of the “whiteness” card. That is, I wonder if the “white-guilt” and “white-apologia” and “white-privilege” view of the world cannot exist except also to give birth to a “white-pride” backlash, even if the latter is seldom expressed overtly—it being politically incorrect to do so.

Confronted by someone who is constantly bludgeoning me about the evils of colonialism, urging me to tear down the statues of “dead white men,” insisting that I apologize for what my white forebears did to the “peoples of color” in years past, demanding that I settle my historical indebtedness via reparations, and so forth—I well might begin to ask myself, were I one of these “white oppressors,” on exactly what foundations does human civilization in the 21st century stand? I might begin to enumerate the great works of philosophy, mathematics, and science that ushered in the “Age of Enlightenment,” that allowed modern medicine to exist, that gave rise to the core of human knowledge about the origins of the species or of the universe. I might begin to tick-off the great artistic achievements of European culture, the architectural innovations, the paintings, the symphonies, etc. And then, were I in a particularly agitated mood, I might even ask these “people of color,” who think that they can simply bully me into a state of guilt-ridden self-loathing, where is “their” civilization?

Now, everything I just said exemplifies “racist” and “white supremacist” rhetoric. I wish to stipulate that I would never actually say something like that myself. I am not here attempting to justify that position. I am simply noticing that, if I were a white person, it might tempt me, and I cannot help but think that it is tempting a great many white people. We can wag our fingers at them all we want but they are a part of the racism-monger’s package. If one is going to go down this route, one has got to expect this. How can we make “whiteness” into a site of unrelenting moral indictment without also occasioning it to become the basis of pride, of identity and, ultimately, of self-affirmation?

One risks cancellation for saying this, but the right idea is the idea of Gandhi and Martin Luther King: to transcend our racial particularism while stressing the universality of our humanity. That is, the right idea—if only fitfully and by degrees—is to carry on with our march toward the goal of “race-blindness,” to move toward a world where no person’s worth is seen to be contingent upon racial inheritance. This is the only way to address a legacy of historical racism effectively without running into a reactionary chauvinism. Promoting anti-whiteness (and Black Lives Matter often seems to flirt with this) may cause one to reap what one sows in a backlash of pro-whiteness. Here we have yet another unspeakable truth which, as a responsible black intellectual, it is my duty to apprise you of.

On the unspeakable infantilization of “black fragility”

I would add that there is an assumption of “black fragility,” or at least of black lack of resilience lurking behind these anti-racism arguments. Blacks are being treated like infants whom one dares not to touch. One dares not say the wrong word in front of us; to ask any question that might offend us; to demand anything from us, for fear that we will be so adversely impacted by that. The presumption is that black people cannot be disagreed with, criticized, called to account, or asked for anything. No one asks black people, “What do you owe America?” How about not just what does America owe us—reparations for slavery, for example? What do we owe America? How about duty? How about honor?

When you take agency away from people, you remove the possibility of holding them to account and the capacity to maintain judgment and standards so that you can evaluate what they do. If a youngster who happens to be black has no choice about whether or not to join a gang, pick up a gun, and become a criminal, since society has failed him by not providing adequate housing, healthcare, income support, job opportunities, etc., then it becomes impossible to effectively discriminate between the black youngsters who do and do not pick up guns and become members of a gang in those conditions, and to maintain within African American society a judgment of our fellows’ behavior, and to affirm expectations of right-living. Since, don’t you know, we are all the victims of anti-black racism. The end result of all of this is that we are leveled down morally by a presumed lack of control over our lives and lack of accountability for what we do.

What is more, there is a deep irony in first declaring white America to be systemically racist, but then mounting a campaign to demand that whites recognize their own racism and deliver blacks from its consequences. I want to say to such advocates: “If, indeed, you are right that your oppressors are racists, why would you expect them to respond to your moral appeal? You are, in effect, putting yourself on the mercy of the court, while simultaneously decrying that the court is unrelentingly biased.” The logic of such advocacy escapes me.

On achieving “true equality” for black Americans

I am reminded, amidst the contemporary turmoil, of the period after the Emancipation, more than 150 years ago. There was a brief moment of pro-freedmen sentiment during Reconstruction, in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, but it was washed away and the long, dark night of Jim Crow emerged. Blacks were set back. But, in the wake of this setback emerged some of the greatest achievements of African American history. The freedmen who had been liberated from slavery in 1863 were almost universally illiterate. Within a half-century, their increased literacy rate rivals anything that has been seen, in terms of a mass population acquiring the capacity to read. Now, that was really very significant, for it helped bring them into the modern world.

We now look at the black family lamenting, perhaps, the high rate of births to mothers who are not married and so forth—but that is a modern, post-1960 phenomenon. In fact, the health of the African American social fiber coming out of slavery was remarkable. Books have been written about this. Businesses were built. People acquired land. People educated their children. People acquired skills. They constantly faced opposition at every step along the way, “no blacks need apply,” “white only,” this and that and the other, and nevertheless they built a foundation from which could be launched a Civil Rights Movement in the mid-20th century, that would change the politics of the country. As my friend Robert Woodson is fond of saying, “When whites were at their worst, we blacks were at our best.” Such potentiality seems now to have been, in a way, forgotten as we throw ourselves, as I say, on the mercy of the court. “There’s nothing we can do.” “We’re prostrate here.” “Our kids are not doing as well, our communities are troubled, but here we are, and we demand that you save us.”

This is the very same population about which such a noble history of extraordinary accomplishment under unimaginably adverse conditions can be told. So, pull yourself up by the bootstraps is a kind of cliché, and people will laugh when you say it, and they’ll roll their eyes and whatnot. Take responsibility for your life. No one’s coming to save you. It’s not anybody else’s job to raise your children. It’s not anybody else’s job to pick the trash up from in front of your home, etc. Take responsibility for your life. It’s not fair, and this is another, I think, delusion. People think there is some benevolent being up in the sky who will make sure everything works out fairly, but it is not so. Life is full of tragedy and atrocity and barbarity and so on. This is not fair. It is not right. But such is the way of the world.

Here, then, is my final unspeakable truth, which I utter now in defiance of “cancel culture”: If we blacks want to walk with dignity—if we want to be truly equal—then we must realize that white people cannot give us equality. We actually have to actually earn equal status. Please don’t cancel me just yet, because I am on the side of black people here. But I feel obliged to report that equality of dignity, equality of standing, equality of honor, of security in one’s position in society, equality of being able to command the respect of others—this is not something that can be simply handed over. Rather, it is something that one has to wrest from a cruel and indifferent world with hard work, with our bare hands, inspired by the example of our enslaved and newly freed ancestors. We have to make ourselves equal. No one can do it for us.