Culture Wars

Social-Media Oligopolists Are the New Railroad Barons. It's Time for Washington to Treat Them Accordingly

In American First-Amendment jurisprudence, Brandenburg’s name is now a byword for the test that is used in assessing the validity of laws against inflammatory speech—especially speech that can lead to the sort of hateful mob activity that played out at the US Capitol last Wednesday.

In 1964, an Ohio Ku Klux Klan leader named Clarence Brandenburg told a Cincinnati-based reporter that his hate group would soon be holding a rally in a rural area of Hamilton County. In the filmed portions of that rally, which later became the focus of legal prosecution, robed men, some with guns, could be seen burning a cross and making speeches, infamously demanding “revengeance” against blacks (they used another word, of course), Jews, and the white politicians who were supposedly betraying their own “caucasian race.” They also revealed a plan for an imminent march on Washington, DC.

In American First-Amendment jurisprudence, Brandenburg’s name is now a byword for the test that is used in assessing the validity of laws against inflammatory speech—especially speech that can lead to the sort of hateful mob activity that played out at the US Capitol last Wednesday.

When details of the Hamilton County rally were made public, prosecutors successfully charged Brandenburg under Ohio’s criminal syndicalism statute, a 1919 law that, in the spirit of the first Red Scare, criminalized anyone who proselytized “the duty, necessity, or propriety of crime, sabotage, violence, or unlawful methods of terrorism as a means of accomplishing industrial or political reform,” or who voluntarily assembled with any group that had been “formed to teach or advocate” such doctrines.

But Brandenburg’s conviction was famously reversed by the US Supreme Court, on the principle that governments can suppress inflammatory speech only if such speech is “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.” Brandenburg’s words, however hateful, were judged to be protected because they extolled violence and law-breaking only in general terms.

More than half a century later, this 1969 judgment still defines the expansive contours of protected political speech in the United States. Whether you are an antifa member demanding the overthrow of America’s supposedly white-supremacist overlords, or a QAnon fanatic denouncing some imaginary cabal of satan-worshipping pedophiles, you have the legal right to do so insofar as you stick to revolutionary generalities. In nominal terms, this general principle hasn’t changed since Brandenburg was decided.

What has changed is the technological environment in which inflammatory speech is communicated. The Brandenburg court rendered its judgment at a time when extreme forms of hate speech typically were spread in books, self-published pamphlets, or, as with Brandenburg himself, old-fashioned in-person meet-ups. By contrast, when Donald Trump urged his supporters to descend on the Capitol last Wednesday, members of his audience already had spent years firing one another up over social media, while creating, consuming, and recirculating reams of extremist propaganda. Even as they stormed the Capitol, some of them continued to extol the cause in real time, posting photos of themselves pillaging America’s national legislature. Violent mobs have been a feature of political life since the dawn of humanity. But to members of the Brandenburg court, the digital tools that allow every one of us to act as our own newspaper editor, radio host, and TV reality show would have been unimaginable.

It isn’t just the technology itself that has drastically altered the debate about the limits of inflammatory speech, but also the consequent shift in decision-making power from public to private hands. Just a few decades ago, it was taken for granted that government policymakers and Supreme Court justices were the most important decision makers when it came to setting the ground rules on free speech. That’s no longer the case, because the entities that control mass-market peer-to-peer content, software, and monetization—including Google, Twitter, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, PayPal, GoFundMe, and Patreon—are largely unconstrained by any kind of government oversight. These are privately run companies that have aggressively leveraged network effects—the phenomenon by which the value of a user’s network engagement increases in tandem with the participation of other users—to create a communications oligopoly. As a result, crucial decisions about what can and cannot be said in the public sphere are now being made by small groups of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. In some cases, it really just comes down to the up-or-down vote of a single person.

The reason everyone is suddenly talking about this issue is obvious: Twitter’s suspension of Donald Trump’s account. And before proceeding further, it is worth noting that Twitter’s decision seems justifiable to us for at least two reasons.

Firstly—even putting aside Twitter’s own terms of service, and the unhinged conspiracism and demagoguery that have become the president’s signature communications style—his explicit exhortation that followers march directly to the Capitol and take matters into their own hands arguably (if not conclusively) falls under the Brandenburg court’s description of language “directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or produce such action.”

Secondly, and more generally, Twitter is a publicly traded company that is accountable to its shareholders—not to government, voters at large, or even its own user base. And so it can withdraw its services from any user for any reason, or for no reason at all.

This latter rationale explains why the campaign to impose regulatory oversight on social-media companies has never developed (until now, at least) a dependable political constituency: Progressives openly campaign for more anti-hate content measures, and so are cheering on Twitter for its newly proactive approach; while conservatives are naturally leery of telling private companies what to do. As libertarian-minded writer Brian Amerige—a former senior engineering manager at Facebook—wrote in a 2019 Quillette essay on the subject, “we should recognize that none of us are entitled to have… social media services… As customers, we should give them feedback when we think they’re screwing up. But they have a moral and legal right to ignore that feedback. And we have a right to leave, to find or build alternate platforms, or to decide that this whole social media thing isn’t worth it.”

By way of specific example, consider Poland, whose right-wing government is pushing a law that would impose massive fines on tech firms that block content that would otherwise be permitted under Polish law. Even free-speech liberals (such as ourselves) are skeptical of this kind of dirigiste oversight regime—especially one that would be administered, as in the Polish case, by a populist, openly homophobic government that has tried to smear Lech Wałęsa as a communist collaborator and suppressed truthful scholarship about the Holocaust.

On the other hand, the status quo simply isn’t sustainable—because Silicon Valley’s communications oligopoly, being increasingly staffed by young, highly progressive knowledge workers, is no longer even pretending to be ideologically neutral when it comes to content moderation. At Twitter, in particular, feminists who misgender trans women (or dare point out the biological reality of sexual dimorphism) are regularly thrown off the platform on the claim that they are spouting transphobic hate speech, even as their ideological opponents are free to publish rhapsodies about killing ideologically non-complaint “TERFs.” And as Quillete’s editor-in-chief noted in a recent op-ed column in the Australian:

While Apple has just banned Parler from its app store for violating its app store user terms, the company has also lobbied to water down provisions in a recent bill aimed at preventing forced labour in China. Similarly, Twitter allows Iran’s Ayatollah Imam Sayyid Ali Khamenei to tweet repeatedly about Israel being a “malignant cancerous tumour” that has to be “removed and eradicated.” Other threats of violence are commonplace. When the U.S. experienced its “race reckoning” of 2020 following the death of George Floyd—a reckoning that led to widespread rioting, billions of dollars’ worth of property damage and an estimated 25 deaths—there was no crackdown on accounts that encouraged looting, property damage or arson.

Moreover, history shows that there is no natural limit to the expansion of doctrines that provide justification for stifling certain kinds of expression in the name of public morality or ideological purity—including when industry players themselves are put in charge of content moderation. For much of the 20th century, for instance, the content of movies and television were governed by rigidly conservative industry codes that demanded the eradication of any mention of sex, birth control, or homosexuality, on the theory that such content would set young viewers on the road to ruin. In a conservative foreshadowing of today’s progressive social panic over racism, even comic-book publishers formed an industry group to police forbidden themes, following 1954 Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency hearings. As with the Hollywood Production Code, it was stressed that love stories should showcase the “sanctity of marriage” while downplaying “lower and baser emotions.”

In 2021, of course, the cultural shoe is on the other foot, and it is progressives who are hard at work writing, and enforcing, this type of code. And as with Cold War conservatives, they are playing fast and loose with the idea of what kind of content may hurt people.

In the case of Facebook, hate speech is defined as “a direct attack on people based on what we call protected characteristics—race, ethnicity, national origin, religious affiliation, sexual orientation, caste, sex, gender, gender identity, and serious disease or disability… We define attack as violent or dehumanizing speech, statements of inferiority, or calls for exclusion or segregation.” That sounds precise. But in practice, words such as “attack,” “harm,” and “dehumanize” are now tossed about so casually as to make them meaningless. Indeed, on certain issues, it is now common for progressive culture-war combatants to respond to any form of disagreement as a threat to their very “right to exist.” As Amerige notes, “hatred is a feeling, and trying to form a policy that hinges on whether a speaker feels hatred is impossible to do,” which is why these speech-suppression campaigns—like the old conservative social panics they resemble—now carry such a heavy whiff of intolerance.

If Twitter and Facebook were ordinary media sites, offering content created and curated by a limited set of authors and editors (such as Quillette itself), none of this would present much of a problem, as we could rely on the free market to do its work. Don’t like our ideological litmus tests? Try the site down the street.

But Twitter and Facebook aren’t ordinary media sites: They’ve become everyday communications utilities that people use to share their opinions, solicit advice, agitate politically, promote their businesses, find love, connect with like-minded hobbyists, and much else besides. A confused Brandenburg-era FCC regulator might see them as a mash-up of news television, call-in radio, classified ads, a telex, a political rally, and a soapbox.

That regulator might also be struck by how much of the content on these social media—Twitter, especially—consists of people complaining about the medium itself. That’s not because we feel ripped off (these sites are free, after all), but because we feel trapped: So much of a person’s reputational capital now consists of his or her accumulated followers, an asset that takes years to build up but which can be squandered in an instant if one gets suspended (a terrifying proposition for many young professionals, especially since there is typically no real way to appeal the decision to a real human being). As satirist Titania McGrath put it: “Big tech censorship is a right-wing myth. If you don’t like our rules, just build your own platform. Then when we delete that, just build another one. Then when we delete that, just build your own corporate oligopoly. I really can’t see the issue.”

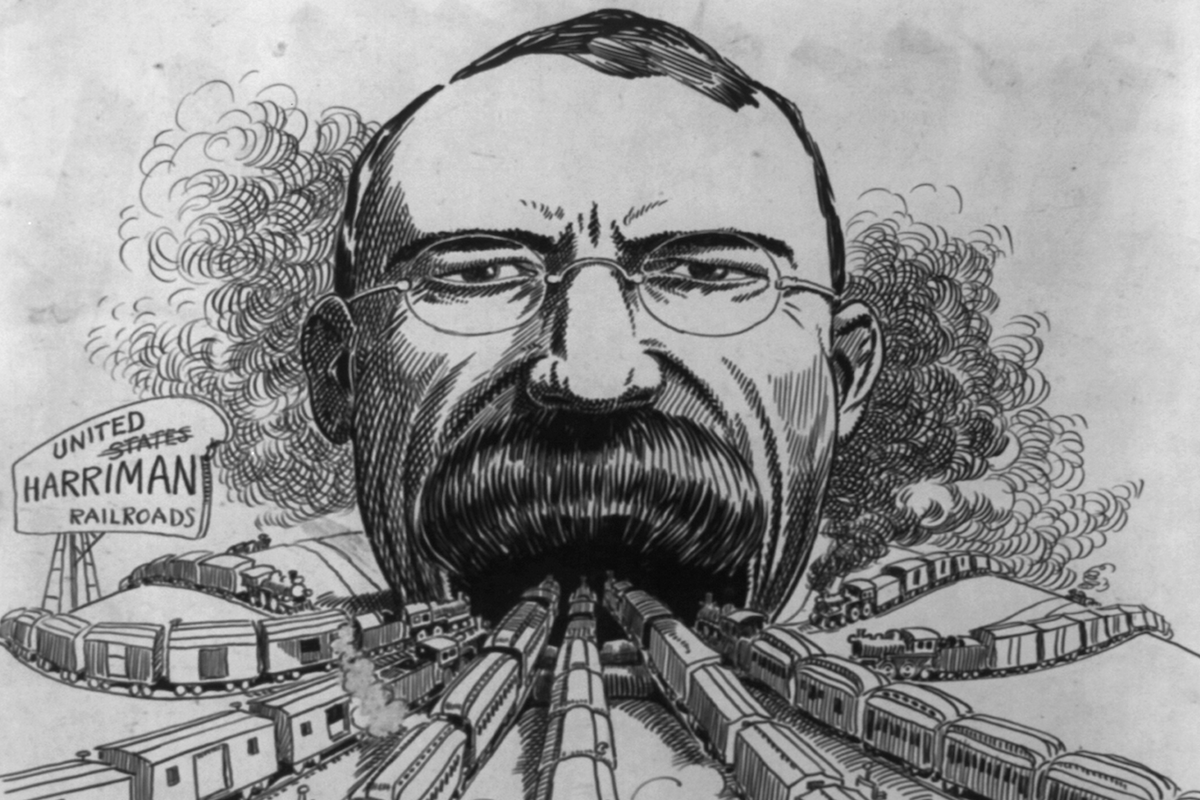

In our view, the most promising solution lies with antitrust law, a policy instrument that has played a major role in the reform of commercial sectors that, like social media, feature built-in network effects, and which lend themselves to monopolistic corporate control—from railroads to computer operating systems. Crucially, unlike other modes of government intervention in the marketplace of ideas (such as the aforementioned Polish model), antitrust law has the benefit of being widely accepted among both mainstream progressives and conservatives as a legitimate instrument of state policy.

On November 20th, 1974, the US Department of Justice put out a press release announcing a civil antitrust suit charging AT&T, which then handled more than 90 percent of the country’s interstate phone traffic, with “monopolizing telecommunications service and equipment.” The suit led to a decade of litigation, the eventual breakup of the Bell system in 1984, and a host of complicated microeconomic effects (including a relative decline in long-distance phone rates vis-à-vis local flat rates) that not everyone applauded. But over time, it also eventually led to the creation of a genuinely competitive communications market, while also preserving the main benefit of the old Bell-managed monopoly system—the ability of any person to call any other person within a coherent, integrated system. In 2021, an individual or business is never required to remain with a provider just so she can keep the 10-digit phone number that sits at the center of her electronic communications identity: She can bring it with her if she chooses to adopt a new provider.

What would such an antitrust model look like if applied to the realm of social media? It’s hard to say, because there are important structural differences between real-time voice communication networks and social media. Moreover, it is unrealistic to expect that a user who migrates from Facebook or Twitter to a much smaller service such as, say, Minds, could expect to bring over anything but a small fraction of her former followers: Everyone has a phone number, but not everyone signs up for every social media site.

But whatever the exact contours of such a policy fix, some element of inter-network portability must be created: A user who voluntarily moves from one social-media service to another should not have to give up an entire lifetime of bilateral relationships. Nor should an anonymous employee of a tech company be able to destroy those relationships—whether on the basis of claimed hate speech or otherwise—without providing the expelled user with a means to export the assets embedded in the deleted account to some other platform.

With Twitter still purging radical right-wing accounts by the thousands, and with much of the American political and journalistic establishment in a lingering state of shock over last week’s fracas in Washington, this is hardly a propitious moment for any grand initiative aimed at reigning in America’s social-media giants. But if Joe Biden and his fellow Democrats don’t address this issue in a reasonable and principled way, they may find themselves undercut by other national governments that, like Poland, have their own agendas.

Since Silicon Valley companies are subject to American legal jurisdiction, the US government has a special opportunity—and, we believe, duty—to acknowledge that social media has now become a fixture of daily life, no less than our phones, our computers, and our travel networks. And the time has come for it to be governed according to the same sort of broad legal principles that have served to balance the power differential between ordinary people and the monopolists who provide them with services.