Art

Wide As the Sky and Deep As the Ocean

The film and the recording revealed a frail man, his mobility and speech compromised by the crippling sclerosis that had probably hastened his decision to leave the music business.

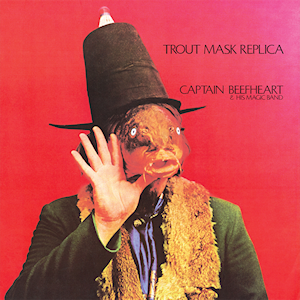

When Don Van Vliet—the painter and musician better known as Captain Beefheart—died 10 years ago today, the obituary in the New York Times described him as “an artist of protean creativity” whose 1969 avant garde rock masterwork Trout Mask Replica paved the way for the post-punk experimentation of Devo, The Fall, Pere Ubu, and The Residents. “If there has ever been such a thing as a genius in the history of pop music,” the British DJ John Peel had once famously remarked, “it’s Beefheart.”

My own introduction to the world of Captain Beefheart came, like many lasting and influential encounters, by chance. I was 13 and out shopping for records, and having bought a couple, I found myself with a pound to spare. Rifling through the bargain rack past the Top of the Pops compilations, I came across an intriguing-looking album called Dropout Boogie. There was no information on the sleeve besides the name of the band and a fish-eye lens photo on the front and back of four serious men in suits who looked more like a mafia cell than musicians (a deliberate record company attempt to copy the cover of the Rolling Stones’ High Tide and Green Grass, and appeal to the same market). Intrigued, I handed over 99 pence, took the record home, turned my new record player all the way up (so as to keep the neighbours appraised of my impeccable taste), and dropped the needle onto Side One.

What emerged from my speakers over the course of that first side remains one of the most perfectly curated slabs of musical development I have heard, travelling from blues to soul to psychedelia in six glorious moves. A lonely slide guitar intro opens the record, followed by a voice that sounds like a blues holler from another time, and at 30 seconds, the band clatters in and the opening track “Sure Nuff ‘n Yes I Do” extended its salacious welcome. This was followed by the propulsive clang of “Zig-Zag Wanderer” before “Call on Me” introduces a note of plaintive soul. “Dropout Boogie” is the first intimation of Beefheart’s percussive vocal power; “I’m Glad” is a pure soul tune in which he seems to channel the catch-in-the-throat technique of Solomon Burke in a rueful reminiscence of a lost love. It was as Beefheart sneered the word EEELECTRISSUHTAY over the discordant opening of the side’s final track that my mother ran into my room and demanded I turn that rubbish off. With those six songs, Captain Beefheart had driven a permanent wedge in the generation gap.

Don Vliet (the “Van” was adopted later) was born in 1941 in Glendale, California, the only child of Glen and Sue Vliet. His father drove a Helms bread truck and Don helped with the deliveries after his father’s heart attack. At school, he met Frank Zappa and the two boys became friends, devouring stale pineapple rolls from the bread company and rhythm & blues records. Reportedly a childhood prodigy in art and sculpture, Vliet’s work was featured on a local television network. Notwithstanding this early promise, his parents discouraged his artistic leanings and prevented him from accepting a scholarship to study in Europe. Instead, he pursued his growing interest in music with his schoolmate and the two boys co-wrote the screenplay to an unproduced film entitled Captain Beefheart vs the Grunt People. It was from here that his stage persona evolved. Zappa, a sophisticated musician and composer, would go on to form The Mothers of Invention. Beefheart, an intuitive and untrained musician, would establish his more blues-oriented Magic Band. Both were iconoclasts of extreme creative vision and difficult men who imposed strict and sometimes tyrannical rules on band members and collaborators. Nevertheless, between them they produced some of the most fascinating music of an era already rich in creative unorthodoxy.

The record I had picked out of the bargain bin, I later discovered, was a 1970 reissue of Safe as Milk, Beefheart and the Magic Band’s debut album, released in 1967. With the teenage Ry Cooder providing lead guitar lines, it marked the end of the band’s nascence as a hard-driving blues combo. By no means as challenging as the music for which Beefheart became famous, it was already apparent that this was not a conventional blues outfit, or particularly suited to any musical category. A lot of Beefheart’s earliest material is now available on YouTube, and the video for their first single (a 1966 cover of Bo Diddley’s “Diddy Wah Diddy”) offers an indication of what was to come. By the time of its release, the band had already spent a few years building a formidable live reputation throughout California.

America’s record industry, mindful of the success of British blues revivalists like The Animals and The Rolling Stones, were hunting for a home-grown version. Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band seemed to fit the bill. The video, however, shows the tension already apparent between commercial ideal, creative delivery, and creative aspiration. A California band was expected to shadow the influence of The Beach Boys, and so the song is performed in the middle of a beach party full of happy blonde teenagers in swimsuits chugging away to the music. Among them, dressed in a tie and waistcoat, stands the Captain, like a baleful raincloud over this sunny happiness. The video doesn’t really work, and the song, although magnificent, lacks the lightness and the pop sensibility of a commercial success like, say, Them’s “Baby Please Don’t Go.” But it was already clear that while the musical road ahead would not be a straight one, it would be tense and never less than fascinating.

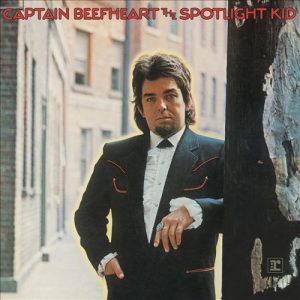

Having digested his debut, I resolved to catch up with what were then Beefheart’s latest releases: The Spotlight Kid, and then Clear Spot, both of which were released in 1972. Both records were triumphantly mystifying and rewarding for my teenage soul. And their obscurity meant they were shrouded by a sense of insider knowledge I hadn’t yet penetrated—I was still an outsider and had to earn my right to be a fan. The Spotlight Kid‘s cover photo showed Beefheart looking vaguely like a plump, goateed Las Vegas-era Elvis, and the back was adorned with strange pen and watercolour portraits of band members with names like Zoot Horn Rollo and Winged Eel Fingerling. Short poems about each of them hinted at Beat literature and an obvious love of wordplay, pun, and aphorism. It’s a modern blues album, with tight arrangements providing the perfect complement to Beefheart’s lyrical vision and guttural roar. From the record’s opening line—”The moon was ah drip on ah dark hood”—through the impression of two hurtling trains in “Click Clack” to the flickering shadows in “Glider” (“I feel like an outsider”) the record offers a strange but coherent and compelling view of the early ’70s American landscape.

Clear Spot was packaged in a translucent plastic sleeve that quickly disintegrated, and again provided little information about the contents besides strange names and references to eccentric instrumentation (wings, tattoos, glass appendage). It’s a more schizophrenic record, alternating between some surprisingly tender blue-eyed soul tunes (“Her Eyes are a Blue Million Miles”) and blues frenzies (“Circumstances”; “Big Eyed Beans from Venus”). It’s as if “I’m Glad” and “Electricity” from Safe as Milk had been extended to fill a whole album, and in that sense, the record is probably one of the most enjoyable in the band’s canon. But the music on both of these back-to-back releases was wonderful. To my ears, these two records seemed to be logical developments from the musical palette of the first. What I didn’t realise at the time was that they were a step back to a more accessible sound after an intervening period of creative and behavioural extremism.

Van Vliet’s financially self-destructive habit of signing conflicting contracts made some of his older records somewhat difficult to obtain, but when I finally tracked them down, a much clearer picture of his musical journey emerged. I discovered that, between Safe as Milk in 1967 and Clear Spot and The Spotlight Kid in 1972, Beefheart had released four albums: Strictly Personal in 1968, Trout Mask Replica in 1969, Lick My Decals Off, Baby in 1970, and Mirror Man in 1971 (although the songs were probably recorded in 1967). The first of these is a set of strange pop and blues-inflected tunes overlaid with an intrusive mash of psychedelic sound effects, and the last is basically an extended blues workout. Sandwiched between them were two staggering masterpieces of the avant garde that still sound like timeless arrivals from a parallel musical universe.

Lick My Decals Off, Baby marked the arrival of Captain Beefheart and the Magic Band at their experimental destination point before they returned to a more orthodox blues sound. But its immediate predecessor Trout Mask Replica, produced by Frank Zappa, blazed the trail to that endpoint and represents the greater artistic achievement. Although both records were released on Zappa’s Straight Records label, each has a very different sound—possibly the consequence of an important change in band personnel and the way in which the new line-up interpreted and organised Beefheart’s musical thoughts. He was an exceptional blues harmonica player and could certainly get a lot of noise out of a saxophone, but he wasn’t a trained musician. He needed someone who understood notation and arrangement to translate and transmit his sometimes inchoate musical ideas.

On Trout Mask Replica, that job was handled by John “Drumbo” French, a percussionist and drummer with prodigious polyrhythmic ability as well as the patience to notate the parts whistled at him by the Captain. By the time of the Decals record, Drumbo had been kicked out by Beefheart (who it is said pitched his erstwhile collaborator down a flight of stairs) and replaced by Art “Ed Marimba” Tripp, a more classically trained percussionist whose nickname provides a hint of the very different drum sound he brought to the band. The songs were arranged by the band’s lead guitarist Bill “Zoot Horn Rollo” Harkleroad and his prowess is especially evident in the complex instrumentals. Consequently, Decals has a frantic energy that makes it very hard to relax to the record and immerse oneself in its development over two sides. A collection of marvellous songs that somehow do not add up to a coherent record, the album nevertheless found some success in the UK after it was energetically championed by John Peel.

Trout Mask Replica, on the other hand, is a mesmerising Gesamtkunstwerk that manages to identify, chart, and sieve 20th century American music through a distinctively unique avant garde sensibility. It certainly isn’t an easy listen, though. In an interview about the record, The Simpsons creator Matt Groening described his reaction when he played it for the first time: “It was the worst dreck I’d ever heard in my life. They’re not even trying! They’re just playing randomly! But then I thought, ‘Well Frank Zappa produced it, so maybe… maybe if I give it another play.’ So, I played it again, and I thought ‘It sounds horrible… but they mean it to sound this way.’ And about the third or fourth time, it started to grow on me. And the fifth or sixth time, I loved it. After the seventh or eighth time, I thought it was the greatest album ever made, and I still do.”

The record is a discordant blend of blues, distilled down to its most basic components, and jazz—particularly the free jazz pioneered by the holy sax sextet of Ayler, Coleman, Coltrane, Kirk, Sanders, and Shepp who were then pushing musical limits in search of experiential and spiritual truth. Van Vliet knew Roland Kirk and was a great admirer of his virtuosity. He knew and was fascinated by the improvisatory approach of Ornette Coleman and the sound he could get from his plastic saxophone. And he had a deep knowledge of the blues, having spent endless hours with Zappa exploring the most obscure releases in the genre’s back-catalogue as they planned their first band and developed the Captain Beefheart persona. These influences were then further combined with an awareness of classical music’s move away from the diatonic system and its realisation in the works of Bartok, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Stockhausen and, in the US, Ives. The upshot was something extraordinary. At allmusic.com, Steve Huey describes it as:

A fascinating, stunningly imaginative work that still sounds like little else in the rock & roll canon… As one might expect from music so complex and, to many ears, inaccessible, the influence of Trout Mask Replica was felt more in spirit than in direct copycatting, as a catalyst rather than a literal musical starting point. However, its inspiring reimagining of what was possible in a rock context laid the groundwork for countless future experiments in rock surrealism, especially during the punk/new wave era.

Some of the songs—such as “China Pig,” “Well,” “The Dust Blows Forward ‘n The Dust Blows Back,” “Orange Claw Hammer”—sound like rediscovered blues field recordings from a distant era, channelling performers like Son House, Robert Pete Williams, and Charlie Patton filtered through an expressive lyricism. “Hair Pie,” “Pena,” “The Blimp,” and “Steal Softly Through Snow,” meanwhile, are wild and apparently random blasts of pure noise, but as precisely notated as any modern classical work. A track like “Neon Meate Dream of a Octofish” demonstrates Beefheart’s Dadaist sensibility—a stew of pure sound from which a stream of words arises building meaning out of assonance. Other songs offer a reminder of his Beat sensibility. And throughout it all, the record propels itself forward as the band crash through 28 songs they had spent more than a year rehearsing at 4925 Ensenada Drive in Woodland Hills, drilled by Beefheart, their demented musical sergeant-major. Listen to “Moonlight on Vermont”—a relatively straightforward rock track in which each musician is slightly (and deliberately) out of time with the others. The record is filled with peculiarities like these and it’s an extraordinary achievement—an ostensibly simple and chaotic sonic experience that belies the painstaking intricacy and care with which it was created.

Beefheart cultivated his reputation as an eccentric sage by punctuating his interviews with enigmatic aphorisms: “If you want to be a different fish, you better jump out of the school”; “It’s not worth melting into the bullshit to find out what the bull ate”; “The way I touch the world is very gingerly. Give me lack of people.” Musical tastes, however, evolve and Beefheart’s progress through the mid-’70s became uncomfortably mainstream and consequently less than interesting to my broadening range of cultural concerns. However, the late ’70s and early ’80s saw him re-emerge with a new bunch of young musicians in thrall to his legacy. They acted as the interpretive spur that drove him to deliver an astonishing triptych of records that capped his musical career. Perhaps inspired by his obvious influence on comparatively successful post-punk material released by Public Image Limited and Pere Ubu, his new work revisited all his lyrical and musical preoccupations but with a fresh energy.

1978’s Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) overflows with exuberance. “Floppy Boot Stomp” is a country hoedown stomp that somehow flops rather than stamps; “Tropical Hot Dog Night” is a Latin mambo groove with spiky guitar lines that prefigure Marc Ribot’s work with Tom Waits. The rhythm of the title track is famously inspired by the sound of his car windscreen wipers in the rain. The record had a somewhat complicated gestation and included previously unrecorded old songs and poems alongside new material, but it marked a triumphant return. 1980’s Doc at the Radar Station had a harder edge, but it is even more dynamic.

The record, wrote Ken Tucker in a review for Rolling Stone upon its release, “comes charging at you… the artist and his art go on a cultural rampage, ripping and tearing at dense, lush undergrowths of melody while hurling imprecations of the airiest, most elliptical wit.” Songs like “Ashtray Heart,” a bitter reflection on discarded love, the extended tone poem “Brickbats,” and the aggressive “Dirty Blue Gene” have the energy of the material Beefheart had produced more than a decade earlier. Complicated compositions like “Flavour Bud Living” display Beefheart’s exploding note theory, according to which each note is to be played as if it had no relation to the note that preceded it—so no sustain, echo or reverb was permitted, just every brittle note in glorious isolation.

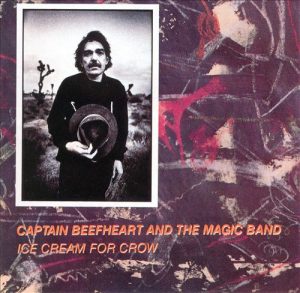

Beefheart’s final album, Ice Cream for Crow, was released in 1982 and is at once more subdued and more frantic than the others. As with the two preceding albums, some of the material dates back more than a decade and this record feels, in retrospect, like a final attempt to offer a definitive distillation, purification, and summation of a 20-year career. So “Ice Cream for Crow” revisits nature and landscape, “Ink Mathematics” employs word association with a playful emphasis on sound before meaning, and, most movingly, “The Thousandth and Tenth Day of the Human Totem Pole” is an evocative poem backed by a score comprising much of the musical DNA that makes Captain Beefheart’s sound so distinctive, down to the last saxophone parp.

All three records featured art by Don Van Vliet, with the last showing one of the paintings he made using a window blind as his canvas. The video for “Ice Cream for Crow” featured the band under the Californian sun of the Mojave Desert, holding up large canvases of semi-abstract oil landscapes. It ended with Beefheart by a window pulling down the blind and disappearing behind it. The signs were clear—the 40-year-old inspiration to a post-punk generation was looking to scratch his creative itch in other ways. A long-time inhabitant of a trailer in the desert, he retired with his wife to northern California in 1982 to paint and draw full-time. His first major exhibition was held at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco in 1985, followed by numerous exhibitions in the US and Europe.

Nearly a quarter of a century after I first stumbled across Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band during a record shop browse, I curated the first UK museum exhibition of the art and work of Don Van Vliet. To coincide with the exhibition, the BBC produced a documentary (above) about his life and work, narrated by John Peel. In addition to his art, I wanted the exhibition to celebrate his achievements as a musician, a poet, and a wit. Curatorial life before the Internet was a mix of perseverance, word of mouth, luck, false leads, chance connections, meetings, and pure serendipity in the detective work necessary to hunt down significant works.

One such introduction led me to the filmmaker Anton Corbijn who had photographed Beefheart for the cover of the final album and who kindly lent some of his art collection and photographic portraits for the exhibition. The exhibition also spurred him to visit Van Vliet and make a short film about him entitled Some YoYo Stuff. Around the same time, Beefheart recorded a selection of his poems, and I included a CD of these readings in the exhibition catalogue. It turned out to be his final release—a downbeat but moving codicil to a recording career that had begun more than 30 years earlier.

The film and the recording revealed a frail man, his mobility and speech compromised by the crippling sclerosis that had probably hastened his decision to leave the music business. But they also showed the wit, determination, and charm that made his best work so fascinating and pleasurable. And the art sang! Just as his music had dismantled and reconstituted US blues and jazz, so his art reworked the US’s key mid-20th century contribution to that medium—abstract expressionism—according to his own thoroughly unique sensibilities and preoccupations. Influenced perhaps by the tonal range of Franz Kline and Clyfford Still, but also the aggression and shallow-focus of contemporary German Expressionists like Georg Baselitz and A.R. Penck, Beefheart’s large oils marked a triumphant interrogation of the desert landscape, the imagery of his poems. Indeed, many of his works are named for a song lyric or a line of poetry, and in their frantic strokes and unmodulated palette, they evoke the fractured and sometimes brittle focus of his music. Those paintings proved to be the final artistic expression from someone who could do nothing but create.