Activism

Cuba’s Doomed War on Independent Art

There were seven police officers, all dressed as civilians. They arrived at the improvised Havana music studio on the morning of Monday, September 28th, kicked down the door and found their target—Maykel Castillo Pérez, a well-known Cuban rapper and human rights activist who was in the process of recording a new song. They beat Castillo (better known as El Osorbo), dragged him out of the house, and took him to the Castillo de la Estación de Policía—a colonial-era fortress that serves as the National Revolutionary Police headquarters. There, Osorbo was incarcerated in a tiny cell without being informed of the charges against him or given access to legal counsel.

When news of Osorbo’s abduction spread, the artist Luis Manuel Otero Alcántara, Osorbo’s wife, and a handful of other supporters went to the police station to demand the rapper’s release. “We told the officers that we wouldn’t leave until Maykel was freed, even if we had to sleep in jail, too,” Alcántara told me. But officers eventually apprehended these supporters, too, and dispersed them to other facilities, in distant parts of the city. At midnight, Osorbo was released. There is no official record of his arrest or detention, and international human-rights organizations didn’t have enough time to respond—a pattern that has become part of the Cuban government’s new playbook for suppressing dissent.

For Osorbo, this kind of episode has become a recurring cost of doing business as an artist. He offers cutting commentary about street problems in Cuba, state censorship, patriotism, poverty, and repression—topics that make the government uncomfortable. In, 2018, he hosted an impromptu hip-hop concert in a small cultural center called La Madriguera, located on Infanta avenue, in the heart of Havana. The space has long been a popular venue for both the capital’s alternative music scene, while also serving a state-sponsored group for young artists and writers, the Associatión Hermanos Saíz. When Osorbo took the stage that night, he reportedly provoked an intense and euphoric reaction. At one point, he and other rappers denounced the recent arrest of another young dissident musician, and yelled repeatedly, “¡No al Decreto 349! ¡No al 349!” Three days later, La Madriguera was closed down, and Osorbo was arrested and imprisoned. He didn’t get out until October 2019.

Decreto 349—Decree 349—is a 2018 Cuban law that allows the state to “regulate” anyone who engages in artistic activities. The category of “official” artist was reserved for those who graduated from state schools or are affiliated with government cultural institutions. Employers who failed to procure the Ministry of Culture’s authorization before hiring an artist could be harshly sanctioned. Amnesty International described the decree as a “dystopian prospect for Cuban artists.”

The law’s enactment was one of several developments that undercut the hopes of reformers who’d imagined that Cuba was on a glide path to freedom following Fidel Castro’s death in 2016. After Washington relaxed sanctions in 2014, the number of tourists visiting the island had increased markedly. New opportunities materialized for entrepreneurs, and there was a nascent renaissance in Cuban fashion and entertainment. Some artists were even able to participate in exchange programs with counterparts in other countries.

Decree 349 signaled that this had been a false dawn. Actress and author Lynn Cruz was canceled for having collaborated with dissident filmmakers. Theatre director Adonis Milán was harassed by state security agents. Performance artist Tania Bruguera, who’d founded an independent organization that supports Cuban artists, was detained for protesting the law. Alcántara, a founder of the first big independent art biennial organized in post-revolutionary Cuba, was repeatedly arrested. I could list countless other examples. And while they are not household names in the West, they are well-known figures in Cuba.

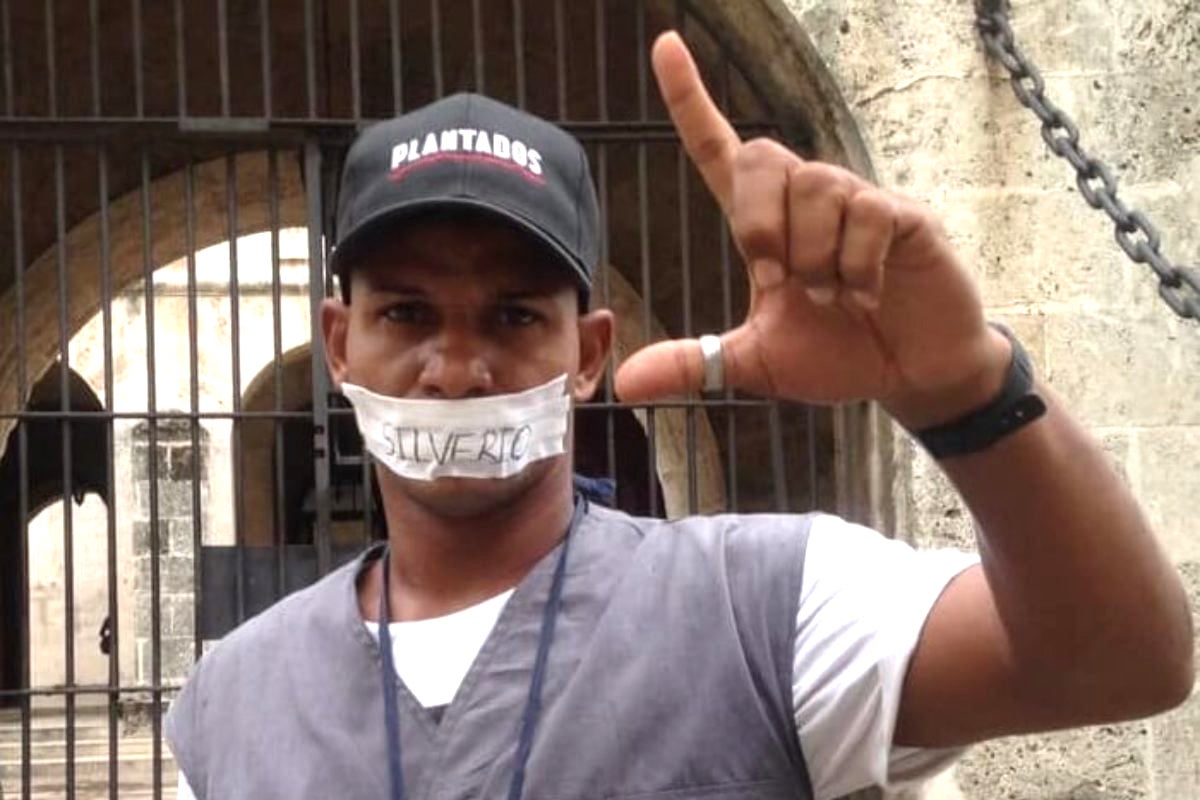

But there was also enormous pushback. Under the slogan No al Decreto 349, activists organized a campaign that brought together artists and supporters both inside and outside Cuba. Open protests took place as well in some cases. And important Cuban public figures, such as musician Silvio Rodríguez, expressed their support. As a result, in September 2019, the regime announced that it would “temporarily cancel” the decree.

But autocratic regimes don’t need a law to justify their harassment of private citizens. In March, Alcántara was arrested in front of his house after trying to attend a protest in favor of LGBTQ rights, and was then prosecuted for “defiling patriotic symbols” though his performance art (in which he’d photographed himself wearing the Cuban flag as an everyday garment). Following protests on his behalf, the regime eventually freed him before trial. But he was arrested again while trying to participate in a public demonstration following the death of a 27-year-old black man on June 24th—effectively the Cuban version of Black Lives Matter. Since then, Alcántara has been arrested on five other occasions.

“This is the same thing the Cuban government has been doing for the last 60 years… the only thing that has changed is the strategy they use,” says Coco Fusco, a prominent Cuban-American curator, artist, and author. “Now they make short arbitrary detentions, of less than 72 hours… They achieve their main objective, [but without] giving international human rights organizations or the press the time to react.”

It’s only a matter of time until Cuban artists gain the freedom that their counterparts in other countries have long enjoyed. A new generation of dissidents, equipped with a different moral vision of the artist’s role in society, is challenging the system like never before. As authoritarians in so many other societies are finding out, the human will to express truth and celebrate beauty can never be permanently smothered by those who prioritize “patriotism” over freedom.