Books

What Is #DisruptTexts?

The disrupters rely on rhetorical devices such as replacing the passive “under-represented” with the active “marginalized,” “erased,” and “excluded.”

Lorena Germán is an award-winning Dominican-American educator and author. On November 30th, she posted this on her Twitter feed: “Did y’all know that many of the ‘classics’ were written before the 50s? Think of US society before then and the values that shaped this nation afterwards. THAT is what is in those books. That is why we gotta switch it up. It ain’t just about ‘being old.’ #DisruptTexts.” That tweet caught the attention of Jessica Cluess, a successful author of Young Adult (YA) fiction, who responded with a lengthy and scornful thread, in which she pointed out that many of those classics were written in defiance of then-existing power structures: “Yeah, that embodiment of brutal subjugation and toxic masculinity, Walden. Sit and spin on a tack.” And, “If you think Upton Sinclair was on the side of the meat-packing industry then you are a fool and should sit down and feel bad about yourself.”

Cluess’s novels have been praised for their “strong sense of social justice” but during the ensuing Twitter mobbing, she was excoriated and accused of racism, violent speech, and harm even so. The following day, she deleted her tweets and posted an unqualified apology, which was predictably mocked and denounced for its alleged insincerity and inadequacy:

This is an apology for Lorena Germán and all who follow me, including my readers, educators, and my publisher. pic.twitter.com/aqEX4iibuU

— Jesskier (@JessCluess) December 1, 2020

A schoolteacher “corrected” Cluess’s apology with red ink as if she were marking homework and posted it on Twitter.

Her agent, Brooks Sherman, was besieged with calls to condemn his client, and when he duly obliged, he was condemned for not condemning her enough. Two days later, he compounded his cowardice by announcing he’d dropped her as a client. Disgracefully, he also repeated the slur that tweets were “racist.” And so on. (The whole sorry saga was discussed by Jesse Singal and Katie Herzog on their Blocked and Reported podcast.)

My statement: pic.twitter.com/XPtLzl3IoE

— Brooks Sherman (@byobrooks) December 2, 2020

The fracas brought #DisruptTexts—an initiative Germán co-founded in 2018—to the attention of a wider audience. The texts these activists seek to disrupt are the classics, otherwise known as the canon. Its website explains:

#DisruptTexts requires that we as educators interrogate our own biases, center the voices of BIPOC in literature, help students develop a critical lens, and work in community with other antiracist and BIPOC educators. Together we will bring about change in society.

There is nothing new or subversive about pointing out that forcing students to slog through Moby Dick might turn them off reading entirely. However, the #DisruptTexts movement is not saying that kids aren’t bright enough to handle challenging texts. Randy Ribay, a public-school teacher and YA author, teaches “critical literary theory” to his high school students. “Of course,” he has remarked, “that’s some heavy stuff and I think most of us didn’t get any of it until college–if at all… some might be thinking, ‘Are they ready for it?’ I know they are.”

In the past, one answer to the question, “Why should we be inflicting Silas Marner on kids?” was “cultural literacy”—a term popularized by scholar E.D. Hirsch, which refers to a person’s ability to understand and communicate using literary and historical allusions such as “witch hunt” or “Trojan horse” or “tilting at windmills.” Children from disadvantaged backgrounds are less likely to acquire this cultural knowledge and consequently less likely to attain a higher command of the English language.

But the #DisruptTexts movement does not conceive of education as the process, inter alia, of transmitting Western cultural heritage to the next generation. Why would they, when they perceive that heritage to be a dark and lamentable catalogue of human crime? Why should they give primacy to literature which interprets the world through the white gaze? “Let us be honest,” Germán admits, “the conversation really isn’t about universality, and this isn’t about being equipped to identify all possible cultural references. This is about an ingrained and internalized elevation of Shakespeare in a way that excludes other voices. This is about white supremacy and colonization.”

To Kill a Mockingbird was voted “America’s Favorite Novel” in a PBS competition in 2018, but #DisruptTexts finds that Atticus Finch is a white savior, and an ineffectual one at that. And Lord of the Flies, a novel featuring “elite, upperclass, private school [students] who are white, cisgender, European males,” is condemned for what it implies about civilization and savagery. So #DisruptTexts has created reading guides which pair the classics with complementary YA literature by authors of color, an intelligent and appropriate remedy for the lack of diversity in the canon. However, the curated list is diverse in everything but theme—five of the eight books are about teenagers of various ethnicities struggling with their identity. One of the recommended reads is Ibram X. Kendi’s Antiracist Baby.

“How is it,” an Illinois high school teacher complained on Twitter, “that we exclusively teach white books written by white men for hundreds of years and suddenly, when you add a couple of books and poems by authors of color, people become concerned about your curriculum choices?” The question is not an unreasonable one. But avoiding boredom, ensuring representation, and handling problematic texts with sensitivity are the methods, not the goal of the movement.

The leaders and followers of the #DisruptTexts movement hold the following truths to be self-evident:

- It is a “professional responsibility to… develop students’ critical literacy skills to question the status quo.”

- Teaching literacy is teaching kids “to discern where and how oppression exists in society, to articulate the oppression we witness or experience and argue for justice, and to strive for a more equitable world.” This “gets at the crux of why we read and write.”

- We must “recognize the ways we are all complicit in perpetuating systemic oppression and consequently responsible for dismantling it.”

- These truths are non-falsifiable because any objection (invariably described as an “attack”) is motivated by white supremacy.

And while the average parent may never have heard of #DisruptTexts, the movement has made a significant impact in public education. Notwithstanding their insurrectionary rhetoric and the clenched fist on their movement’s Twitter profile, these activists are not obliged to disguise their efforts “to fuel resistance and positive social transformation” and “bring the power of literacy for collective liberation.” They are not forced, like the teachers of the McCarthy era, to take a loyalty oath. On the contrary, the co-founders speak at educational conferences and workshops, they are promoted by Tolerance, a subsidiary program of the Southern Poverty Law Center; they are featured on the websites and publications of the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development (ASCD) and the International Literacy Association; they have a regular column in the journal of the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), whose next convention is dedicated to “Equity, Justice and Anti-Racist Teaching”; and Penguin Books has partnered with them to promote YA novels by BIPOC authors.

And all this has been accomplished without (apparently) incorporating #DisruptTexts as a society or non-profit. It is a grassroots, crowdfunded, and teacher-supported movement operating without the accountability which comes with becoming a legal entity.

Nor are these activists simply assuming a fashionable pose when they express their desire to transform society. They are in earnest. And they are convinced that their ideals are so self-evidently correct, their cause so righteous, and the need so imperative, that they openly speak of “throwing out the white canon” and pushing their students to adopt their views. Movement-inspired teachers exchange ideas on Twitter, podcasts, websites, and various forums. “How do I authentically engage with… a predominately White American student population? How do I manage student resistance to these topics?” asks the Pushing the Edge podcast. Another podcaster reports that “it is the stance against To Kill a Mockingbird and The Great Gatsby that has met [with] the most white fragility.”

Some report on their successes and setbacks at the #DisruptTexts website. A white teacher employed at a private Catholic boys’ school reported that: “I realized I could not be subtle or nuanced. I had to be intentional… I had to push them… I dropped my essential questions around the American Dream and added the questions: Whose stories are told and privileged?” She now teaches elsewhere: “No one else at my school was willing to do this work. I ended up leaving my job based on my political views and my need to ask students to question their beliefs.”

Another teacher reported that her interpretation of Lord of the Flies “caused students to LOUDLY challenge ideas that I set forth… In these discussions, I felt exposed and understood what antiracist (or anti-imperialist, anti-white supremacist) teaching should feel like.” She is not entirely satisfied with the results but could not say why: “I came away with questions about who was benefiting as a result of these discussions and who was harmed. Yes, some white students changed their perspectives, but at what cost and to whom?” Nevertheless, she remains a faithful disciple. A Colorado teacher, meanwhile, regretted that she had to follow the prescribed curriculum. This hampered her mission of “inviting my students to move forward using their privilege to dismantle oppression.”

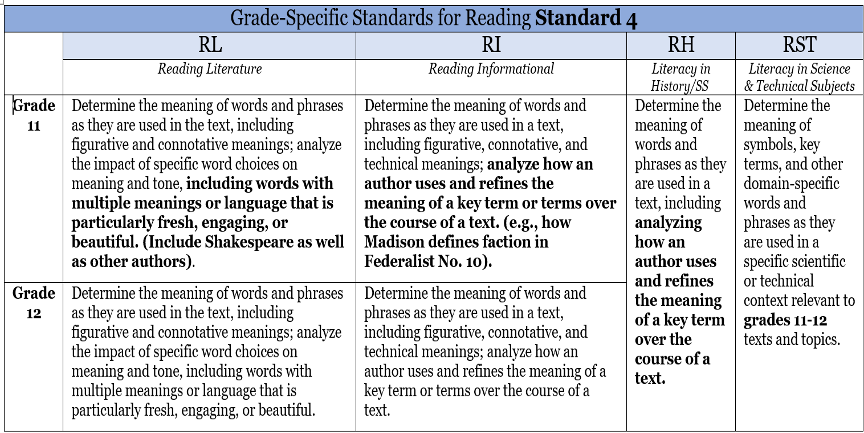

But in many if not most jurisdictions, it is possible for teachers to #disrupt away. Dismantling white supremacy is not a prescribed objective, for example, in the Grade 12 English curriculum for the State of Mississippi. Teaching Shakespeare is. But a determined teacher can bring critical race theory into the classroom with “other authors.”

The language of the curriculum guide is straightforward and unambiguous. The disrupters rely on rhetorical devices such as replacing the passive “under-represented” with the active “marginalized,” “erased,” and “excluded.” They talk “around” issues, not “about” them. They describe the process of indoctrinating themselves or others as a “journey,” and they refer to non-negotiable assertions about race as a “conversation.” The entire endeavour is referred to as “the work.” Their semantic terrain is a minefield of provisos and warnings, where formerly approved terms are declared offensive. “There is no neutral”; “Anti-Black racism manifests itself differently than sexism, and drawing a false equivalence among them can cause more harm”; “Labeling books as diverse reinforces white supremacy.”

As mentioned, several national organizations for educators provide an uncritical platform to the teacher-activists. Randy Ribay, the YA author mentioned above, praised #DisruptTexts in his speech at a workshop for the National Council of Teachers of English, and recommended coaching students to use “three critical lenses—feminist, Marxist, and post-colonial.” (Marx was a racist who believed in the inferiority of non-whites. Presumably Ribay will not be including anti-Maoist works like The Aquariums of Pyongyang or Jung Chang’s Wild Swans on his #othervoices reading list.) Teacher Josh Thompson also endorses #DisruptTexts and calls on his fellow teachers to “fight against systems,” adding that unfortunately “There are a lot of schools where you are told what you have to teach.” This subversive message has not been left in code in a hollow tree for his fellow insurgents to collect once darkness falls. It is posted on the website of the National Education Association.

As a thought experiment, consider a teacher as enthused about Ayn Rand as Ribay is enthused about Marx; or a teacher who believes in promulgating the precepts of Scientology; or a teacher like the late Canadian white supremacist James Keegstra, who taught that the Holocaust is a myth. On what grounds could those teachers be denied the right to propagandize in the classroom if critical race theorists can? If only we could turn to the great thinkers and writers of the past to help us to grapple with these issues.

It would be a bold student indeed who refuses to fall in line with the disrupters’ agenda, dedicated as it ostensibly is to the overthrow of white supremacy and “centering” the plight of the dispossessed. They need only ponder the punishment the activist teachers meted out to Jessica Cluess—a teachable moment, indeed. As Julia Torres, another #DisruptTexts co-founder unironically announced, “We have to really consider how are we rewarding conformity and punishing resistance.”