Latin America

Chile’s Elites Are Creating Another Latin American Populist Meltdown. Voters Must Stop Them

The main hope for Chile lies with the requirement that voters approve any new constitution.

On October 25th, Chile will hold its most important vote since 1988, when General Augusto Pinochet lost a national plebiscite on the question of whether he’d be permitted to extend his rule for another eight years. That 32-year-old referendum result allowed Chile to finally adopt the democratic form originally set out in the country’s 1980 constitution. This time around, the referendum will be on the constitution itself. In an extraordinary development, Chileans are deciding whether they want to create an entirely new constitution from scratch or preserve the existing one.

The first voting option is called Apruebo (Approve), and the second is Rechazo (Reject). Anticipating a scenario in which Apruebo wins, which seems likely, Chileans will also vote on whether the new constitution will be drafted by a mixed constitutional convention of politicians and elected representatives from the citizenry, or a constitutional assembly composed entirely of citizens. In either case, decisions by the body would require a two-thirds majority, and its deliberations must be completed within a year. The constitution they produce would have to preserve Chile’s democratic, republican form of government (at least nominally), and would then be subject to another, second referendum. If the proposed constitution then gets rejected, the current constitution remains operational.

But whatever happens, the process will consist of a newly designated body co-opting a role that properly rests within Chile’s existing institutional framework—a framework that has been used to repeatedly amend the country’s constitution since its creation 40 years ago. Aside from costing taxpayers millions of dollars, the new process portends a period of political instability, and the specter of open-ended conflicts and stand-offs between different branches of government.

To many outside Chile, it may seem strange that what has been arguably the most stable and prosperous country in Latin America would circumvent its institutions in this way, especially when (like many other countries around the planet) it’s facing its worst economic crisis in decades. But in fact, the creation of an entirely new constitutional order has long been an ambition of the Chilean Left. Last year, when the country descended into a period of political chaos, leftists leveraged street protests to pressure President Sebastián Piñera’s government into embracing its constitutional agenda. Even conservative politicians and intellectuals on the Right have expressed support for the process, despite the lessons of history.

Revolutionary efforts to upend existing constitutional schemes have been a common feature in Latin America since the 19th century. As Venezuelan author José Luis Cordeiro has noted, the region has had the world’s “most convoluted constitutional history.” (The Dominican Republic, alone, has had a total of 32 constitutions. And three other Latin American countries have had at least 20.) Some experiments ended well, and many ended badly. Overall, few could argue that this proliferation of new constitutional schemes has provided a net benefit.

At the root of last year’s unrest in Chile was the economic paralysis arising from the statist policies of President Michelle Bachelet, who steered the country in a socialist direction until leaving office in 2018. Piñera, her successor, promised to restore prosperity, but also claimed to endorse Bachelet’s egalitarian narrative. Predictably, he failed to deliver on this internally contradictory agenda. As a result, the country’s economy fell apart, which led to massive demonstrations and violence on the streets of Santiago. This month, a year after those initial protests, there was more destruction, albeit on a smaller scale.

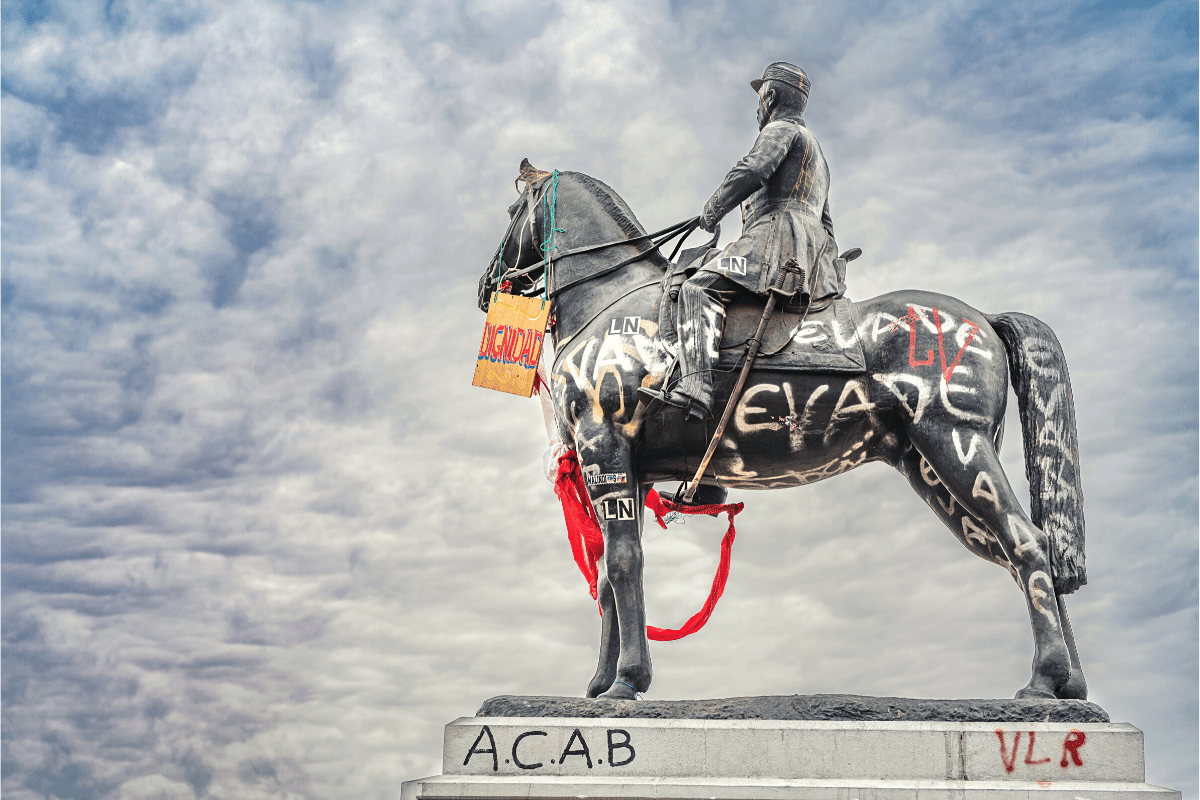

As with similar spasms of street violence in the United States, Canada, the UK, and other countries, criminal episodes have gone unpunished because Chile’s elites feel they lack the moral authority to crack down on anyone acting (or purporting to act) in the name of social justice. Following in the same pattern we’ve seen with the Black Lives Matter phenomenon in North America, politicians, activists, and academics have sought to blame violence on heavy-handed police and military tactics—a message that’s reflected in media coverage, which typically presents the demonstrators as peaceful actors who are goaded into over-reaction by state officials.

Even when people are arrested for violent acts, they often escape prosecution. As then-justice minister Hernán Larraín complained, many judges in Chile bring an openly leftist agenda to their courtrooms, a pattern that may be traced to the training they receive at the country’s ideologically slanted Judicial Academy. As in Portland and Seattle, morale among police officers and military personnel has dropped, causing many to quit their jobs. The idea that a new constitution will provide Chile with an instant solution to all of these various forms of social conflict has become an attractive delusion. Yet the more likely scenario is that it will simply legally encode the unrealistic ideological demands that brought Chile to this point in the first place.

Part of the moral case for radical constitutional reform rests on the idea that the current Chilean constitution is inherently illegitimate because (a) it was created under the autocratic Pinochet regime, and (b) its amendment formula sets an excessively high bar. Yet the constitution has been amended numerous times from 1989 onwards, leading to no fewer than 257 democratically effected changes, more than any previous Chilean constitution. The document’s Pinochet-era legacy is represented in less than a third of the current text. In 2005, moreover, when socialist president Ricardo Lagos put his own ambitious imprint on the constitution, he replaced Pinochet’s signature with his own. After these reforms were passed with nearly unanimous support from both chambers of congress, Lagos declared that Chile finally had created a “democratic constitution” that “represented and united all Chileans.” This is the same constitution that the activists of 2020 claim is morally illegitimate.

Many of the slogans that one hears are holdover from old fights over the supposedly “neoliberal” economic system that has been imposed on Chile under the existing constitutional order. According to Fernando Atria—leader of the Fuerza Común political party, and the most outspoken activist in favor of a new constitution—”the current constitution only benefits those who unilaterally imposed it.” But such claims are belied by an examination of economic indicators over the last 40 years.

Under the period covered by the current constitution, inflation—which had peaked at over 500 percent in 1973—fell below five percent by the 2000s. Between 1980 and 2015, per-capita income in Chile quadrupled to $23,000—the highest growth rate in Latin America. More importantly, life expectancy rose from 69 to 79, and levels of housing overcrowding fell to one-quarter of its pre-1980 levels. The middle class, as that category is defined by the World Bank, grew from 24 percent of the population in 1990 to 64 percent in 2015. Extreme poverty fell from 34 percent to less than three percent. Between 1990 and 2015, the income of the richest 10th of the population grew a total of 30 percent, while the income of the poorest 10th saw an increase of 145 percent. The Gini index, a widely used statistic that measures income inequality, fell from 52 in 1990 to about 48 in 2015. Chile also held the highest position among Latin American nations in the 2019 UN Human Development Index.

Unfortunately, many voters seem more swayed by extravagant promises of the future benefits they will enjoy under a new (and as yet undrafted) constitution. According to poll results published by the think tank Centro de Estudios Públicos last December, 56 percent of Chileans believe that a new constitution would lead to higher pensions, better education, and superior health care, among a long list of other improvements. Like any political process engineered to fulfill utopian promises, the long-run effect could be ruinous.

Several aspects of the current legal scheme played important roles in Chile’s path to prosperity. One was the regulatory regime applied to the Central Bank, which was made independent from political pressures. Governments are prohibited from funding public expenditures with the printing press. And the Central Bank cannot buy up government bonds, even in the secondary market, as a means to affect interest rates. Congressmen cannot propose legal changes that require government spending, a power reserved for the executive branch. And private property is respected under the Chilean constitution: The owner of land that’s seized for public purposes under eminent domain must be compensated at market rates. In addition, it is illegal for the government to exclude the private sector from the provision of education, healthcare, pensions, or any other activity classified as a “social right.”

Such constitutional safeguards were put in place because Chileans had observed the consequences of economic populism, especially spending policies that provided politicians with a short-term popularity boost at the expense of long-term economic viability. The collapse of Venezuela’s economy shows where such populist policies lead. And the same was true of Chile under the socialist regime of Salvador Allende in the early 1970s.

If the Apruebo side wins in the coming referendum, these safeguards against populism will likely vanish. As Americas columnist Mary Anastasia O’Grady recently wrote in the Wall Street Journal, “the new constitution will try to satisfy the populist outcry for social justice by increasing the monopoly power of the state to redistribute wealth.” While a full Venezuelan-style meltdown seems unlikely, Chile could easily go the way of Argentina—a nation with abundant resources that, thanks to dysfunction, has become plagued by corruption, inflation, insolvency, and poverty.

The main hope for Chile lies with the requirement that voters approve any new constitution. If they choose to reject a blueprint that undoes Chile’s current system, their next challenge will be to dethrone the cultural and intellectual elites who’ve turned their backs on free markets and the rule of law. South America supplies all too many cautionary tales of populist movements leading their countries to disaster. Chileans must prevent history from repeating itself while they still have the chance.

Axel Kaiser is a scholar at Adolfo Ibaniez University and senior fellow at the Atlas Network’s Center for Latin America.