Africa

The Coming Post-COVID Global Order

The pandemic crisis is rapidly becoming a civilizational crisis.

The COVID-19 pandemic has devastated economics in the West, but the harshest impacts may yet be felt in the developing world. After decades of improvement in poorer countries, a regression threatens that could usher in, both economically and politically, a neo-feudal future, leaving billions stranded permanently in poverty. If this threat is not addressed, these conditions could threaten not just the world economy, but prospects for democracy worldwide.

In its most recent analysis, the World Bank predicted that the global economy will shrink by 5.2 percent in 2020, with developing countries overall seeing their incomes fall for the first time in 60 years. The United Nations predicts that the pandemic recession could plunge as many as 420 million people into extreme poverty, defined as earning less than $2 a day. The disruption will be particularly notable in the poorest countries. The UN has forecast that Africa could have 30 million more people in poverty. A study by the International Growth Centre spoke of “staggering” implications with 9.1 percent of the population descending into extreme poverty as savings are drained, with two-thirds of this due to lockdown. The loss of remittances has cost developing economies billions more income.

Latin America had seen its poverty rate drop from 45 to 30 percent over the past two decades, but now nearly 45 million, according to the UN, are being plunged into destitution as a result of the novel coronavirus pandemic. In Mexico alone, COVID-19 has caused at least 16 million more people to fall into extreme poverty, according to a study by the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

These trends undermine the appeal of neoliberal globalization across the developing world. The pandemic has forced people to stay in their countries, and has closed off the ability to move to wealthier places. With Western countries themselves in disarray, there’s been a growing temptation to adopt authoritarian controls modeled by China, which appears to have emerged from the pandemic and economic collapse quicker than the rest of the world. The pandemic could boost China’s great ambition to replace the West, and notably America, as the heart of global civilization.

Poverty and pestilence

In the long history of pestilence and plague, French historian Fernand Braudel has noted, there was always a “separate demography for the rich.” As today, the affluent tended to eat better and were often able to escape the worst exposure to pestilence by retreating to country estates. This pattern was evident in Rome, as the city endured growing plagues in the second and third centuries. As Kyle Harper explains in The Fate of Rome, those left behind in the city often became “victims of the urban graveyard effect.”1

These differing impacts were also evident in the late Middle Ages, when plague killed upwards of half Europe’s population. One 14th century observer noted that the plague “attacked especially the meaner sort and common people—far seldom the magnates.” Of course, some of the mighty also died, but far less often than hoi polloi.2 Whether in the towering insulae of Rome, Medieval hovels, or the tenements of the Lower East Side, the poor have suffered from economic dislocation, infection, and death far more than the affluent.3

We may be entering an age that reprises Medieval patterns of mass infections. Three decades ago in The Coming Plague, Laurie Garrett identified the rise of an “urban Thirdworldization” that creates ideal conditions for new pandemics—SARS, MERS, Swine flu, and now COVID-19. These challenges will likely not end even with a vaccine or a weakening of the virus, but may resurge in a different form. Anthony Fauci, director of America’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, already sees potential new viruses incubating in China and warns that more pandemics may arise in the near future.

Although the pandemic started in China and spread first to wealthier countries, developing countries are now experiencing notably higher rates of new infections and fatalities. The world’s highest death rates from COVID-19, outside of Belgium, are in such countries as Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador, Iran, and Mexico. Dr. Azeem Ibrahim, Director of the program on Displacement and Migration at the Center for Global Policy and an adjunct research professor at the Strategic Studies Institute at the US Army War College, predicts the possibility of “devastating death tolls” throughout the developing world. Africa alone, suggests the UN, could see between 300,000 and 3.3 million deaths during the pandemic. India’s reported cases have doubled from around three to six million over the past month, as it has struggled to keep its population socially distant.

During the southern hemisphere’s winter months, South Africa, with a population of 57.8 million, had over 600,000 reported COVID-19 cases, making it the fifth hardest hit country in the world, behind Russia, Brazil, India, and the United States. According to the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), the official death toll is severely under-reported. This is made worse by the near-collapse of the nation’s rural healthcare system. South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province, with a population of over seven million people, had only two infectious disease experts. After the healthcare unions called a strike, standards in a hospital in the provincial capital of Port Elizabeth became so poor that rats were seen feeding on human waste while mothers and infants were left dying.

“Latin America,” notes a recent article in Foreign Policy, has replaced Europe and America as “the part of the world most affected by COVID-19, both by confirmed cases and by deaths.” The region now accounts for five of the world’s top 10 countries with the most fatalities. In September, Mexico ran out of death certificates. As throughout the region, in Mexico the health system has been severely challenged by the virus. According to Associated Press, it has suffered the highest number of deaths among medical personnel of any country in the world. Most deaths, not surprisingly, have occurred among the poor—70 percent, according to another study, have occurred among people with an elementary education or less.

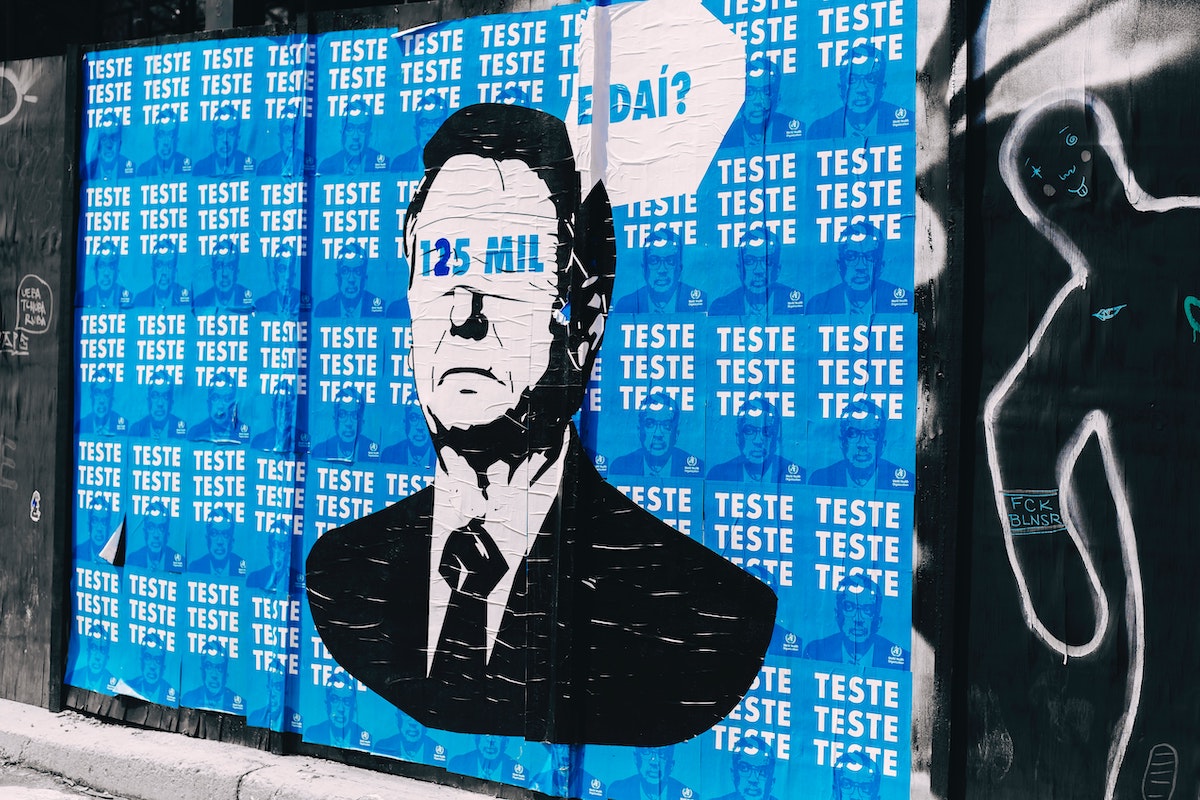

Brazil, the continent’s most populous country, has suffered greatly and seen at least five million infections. That is by far the most in Latin America and the world’s second largest number of deaths after the United States. Its largest city, Sao Paulo, with 12 million inhabitants, has suffered more fatalities than Germany, and its hospitals have teetered on the edge of collapse. Attempts to open up the economy have been reversed recently in that critical city.

Broken hopes

Even before the pandemic, many economies in the developing world were experiencing difficulty accessing world credit markets, and that problem seems certain to worsen. Even among the once ballyhooed BRICS countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—only China seems positioned to make a strong recovery, with the prospect of increasing its share of the world economy. The economy of its greatest emerging rival, India, has lost a quarter of its output after the government implemented the world’s biggest lockdown.

For many of these countries, the massive decline in tourism, as well as the impositions from lockdowns, has proven catastrophic. The International Monetary Fund has predicted that in the Caribbean, where tourism accounts for between 50 and 90 percent of income and employment in some countries, tourism revenues will “return to pre-crisis levels only gradually over the next three years.” This decline will be felt most in larger countries such as Mexico, Turkey, Thailand, and the Philippines, as well as more traditional travel hubs such as Spain and Italy.

Equally critical in many countries is the fact that large parts of the workforce are employed in the informal economy where “face to face” contact is necessary. In India, informal workers represent over 80 percent of the working population and in Africa the figure is 66 percent. In Egypt, the most populous country in the Arab world, over 60 percent of the workforce is in the informal sector. This informal economy, notes Dr. Luis Bernardo Torres, a former official at Mexico’s state bank and now a professor at Texas A and M, is particularly vulnerable since the “majority of the jobs in the informal economy are service-related jobs that need human contact like retail commerce and food services.” When countries lock down, he explains, “people in the informal sector see their income basically drop to zero.” According to Mexico’s Central Bank, the country’s GDP is expected to fall by nearly nine percent this year.

The fallout will be particularly devastating to younger workers, who were already having trouble getting jobs. Even before the pandemic, youth unemployment was approaching 25 percent in Turkey, India, and Iran. In South Africa, over 55 percent of young people are unemployed according to data from the World Bank.

Springtime for dictators?

In his 2005 landmark book The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth, economist Benjamin Friedman suggested that “expanding opportunities” are critical to nurturing “the human attitudes that together sustain an open, tolerant, and democratic society.”4 But with the pandemic generating “increased geopolitical instability”—as the Depression did in the 1930s—the ideal conditions now exist for the rise of strongmen and reinforced existing authoritarian regimes.

Iran’s initial response, for example, was to deny that a crises was occurring, a position that led to subsequent accusations of a cover-up. The minister of health appeared on live television to dismiss the virus as not serious, even though he was already infected. At least 17 Iranian officials had been killed by the virus by March 25th, including an advisor of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. But in response, the Iranian theocracy has only doubled down on its Islamist ideology. Imams refused to ban large prayer gatherings in the holy city of Qom even as authorities dug mass graves so large they could be seen in satellite photos. The additional impact of American sanctions on the Iranian healthcare system has left the country with little access to critical medical equipment for frontline staff, and many nurses and doctors have died. Amazingly, the supreme leader refused international help and instead promoted a conspiracy theory that the USA produced a special version of the virus that disproportionately affected Iranians.

The response of Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, meanwhile, was characteristically authoritarian. When the opposition established a wealth fund to help those worst affected, the government refused to work with the opposition-controlled municipalities and cracked down even more on them—150,000 healthcare workers were purged from their positions. The regime may have been ineffective in battling the virus, but it successfully exploited the pandemic to increase its grip on power by, for example, passing legislation to widen state censorship. Journalists were jailed for spreading news about the pandemic on social media. Even when the government sought to release prisoners from jail due to COVID-19, they specifically did not include political ones.

African regression

Until the pandemic, Africa seemed to be heading towards greater liberalization and integration into the world trade system. This process now seems to have shifted into reverse. In Angola, Kenya, and Uganda, people have been killed by security officials enforcing lockdowns and others have been beaten and shot. The pandemic could be the last straw for South Africa. Once a source of hope and aspiration, some South Africans now fear that the country will end up as another authoritarian “failed state.”

At the onset of the crisis, President Cyril Ramaphosa established a command council that allowed ministers to rule by decree, thereby undermining the rule of law. The pandemic response has been militarized—the government mobilized the army and for the first time since the end of apartheid, soldiers were back on the streets. The regime issued absurd decrees restricting exercise and the buying of alcohol and cigarettes. Ramaphosa’s initial three-week lockdown was extended through the winter until September, making South Africa’s lockdown to date the second longest in the world behind that of Argentina. Unsurprisingly, black workers have suffered the biggest losses; before the pandemic, two-thirds lived in poverty and they have now lost jobs at almost three times the rate of white workers, creating the conditions for racial resentment. As in Turkey and Iran, the pandemic has provided the South African government with an ideal pretext for the expansion of its censorship laws by threatening to jail or fine anyone who spreads “fake news.”

India and Latin America

Even developing countries with strong democratic traditions—most importantly India—are now moving in a more despotic direction. India’s prime minister Narendra Modi has used his country’s lockdown as an opportunity to intensify human rights abuses not only in the Kashmir region, but also on his own supporters. Police and soldiers were seen on social media beating defenseless citizens in India’s overcrowded slums as they tried to enforce impossible social distancing rules.

The Hindu nationalist government has refused to condemn extreme elements that have blamed the Muslim minority for the spread of COVID-19. As in many developing countries, civil order is weakening. Rail and bus services were shut down, leaving thousands of migrant workers stranded and resulting in disruption of the essential food supply. The Indian government has also expanded censorship and asked the Supreme Court to order all media outlets to close so that only the government’s “official version” of the health crisis could be disseminated.

But the greatest dangers to democratic rule may emerge in Latin America. Mexico and Brazil, for example, ruled respectively by populists from the Left and Right, have both proved ineffective at controling the pandemic. Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador has consolidated power, changed the Mexican constitution to allow the military to patrol the streets and detain civilians, and is widely considered the most dictatorial president there in 30 years, even seeking to break tradition so he could prosecute previous leaders. He has also attacked reporters in Trumpian fashion.

Similar patterns have emerged in Brazil, where right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro has, like Obrador, downplayed the crisis. Instead, he has sought to consolidate power and push his own ideology, which emphasizes conservative social values and economic growth. Like his counterparts in South Africa, he has approached the crisis in a militaristic fashion, even appointing Eduardo Pazuello, an army general with no medical experience, as the interim minister of health.

The pandemic as civilizational crisis

The pandemic crisis is rapidly becoming a civilizational crisis. The halting and often clearly muddled response in the West, most notably in the United States and the UK, has undermined the credibility of democratic institutions in much the same way as the financial crisis of 2008. Governments in Paris, London, and Canberra have imposed lockdowns that disproportionately affect poorer, often minority-dominated areas. The economic and social impacts have been so harsh that more medical experts are now calling for an end to lockdowns, reasoning that the economic and social damage is worse than the disease.

This perceived choice between safety and debilitating poverty is particularly unpleasant for poorer countries. Some countries may turn to China, where the virus first appeared and rampaged, but where it now appears to be in retreat, perhaps as a result of the regime’s very strict policies. What the Guardian has labeled a “brutal but effective strategy” has helped China’s economy mend more quickly, as factories, stores, and restaurants re-open. The methods needed to achieve this success—harsh discipline on a military level—may seem abhorrent to Westerners, but China is making a powerful case for social control as a means of dealing with pandemic, and returning to economic growth.

China is now engaging in “medical diplomacy,” taking advantage of its increasingly dominant position in producing protection gear and other critical equipment. It has offered advice and medical supplies, not only to developing countries in Africa and Latin America, but also to embattled European ones such as Italy and Spain. The more Western economies appear to be economically and socially failing due to the pandemic, the more they may be tempted to embrace China’s more authoritarian approach.

It may be hard for those of us suffering lockdowns and economic disruption to consider the pandemic’s effects on distant and often economically marginal countries. But if the growing crisis in the impoverished developing world—nearly half of all humanity—is not addressed soon, the implications for the future of democracy could be profound indeed.