I knew a few social justice campaigners in high school. They were advocates, they liked to remind the rest of us, and they were endowed with holy outrage and an acute awareness of inequality and a passion for tolerance that never quite translated into actual kindness. They wore t-shirts that bore slogans like “The Future Is Female,” they crusaded against “oppressive” dress codes, and they confronted a patriarchal grading system. They were practised in the art of derailing conversation with accusations of heteronormativity or cultural appropriation. The battles they won (“We can wear tube tops now!”) were triumphs of resistance, while those they lost only accentuated the ubiquity of the inequity du jour. No matter how petty and irrational their grievances became, these students eluded criticism from peers, teachers, and administrators alike. Nobody wanted to take them on. After all, who wanted to argue with the pursuit of justice?

Throughout high school, conversations were had, discourses were dismantled, lived experiences were brandished, and I sat through all of it silently. I was more bored by the whole thing than angry, and I had other problems on my hands. I spent my gap year in psychiatric hospitals all over the western half of the country, being treated for an array of mental illnesses and symptoms that no one seemed to understand. A few weeks after I was accepted to colleges no one thought I’d be well enough to attend, I received a diagnosis of autism. It soon became clear the professionals’ misunderstanding of my condition had hindered my recovery. The treatments I’d attempted and failed tended to be unsuccessful with autistic patients, and the symptoms that had baffled so many clinicians made sense in this new diagnostic context. I was transferred to another hospital where the doctors had experience with patients on the spectrum. Contrary to everyone’s expectations, I was discharged by the middle of August, just in time to start my freshman year at Stanford—and my foray into advocacy.

For most of my life, I had taken my intense introversion, obsessive thinking, and social clumsiness as evidence that there was something deeply wrong with me. Many of the adults around me seemed to agree. I spent most of my adolescence undergoing treatment for a vast constellation of psychiatric symptoms, and I was used to having every morsel of my behavior and cognitions dissected and pathologized. I was too rigid, anxious, obsessive, and compulsive. I didn’t socialize enough. I spent too much time on my schoolwork, procrastinating and panicking. My faults were meticulously recorded in medical charts and psychological assessments, an ever-growing inventory of ways in which I needed to be fixed. If I took my medication and put enough effort into treatment, the doctors informed my parents, I would perhaps one day reach that mythical state of recovery, wherein I would enjoy slumber parties and trips to the mall and the consistent achievement of developmental milestones. What a relief that would be for my family, for everyone, for all of my faults to be erased.

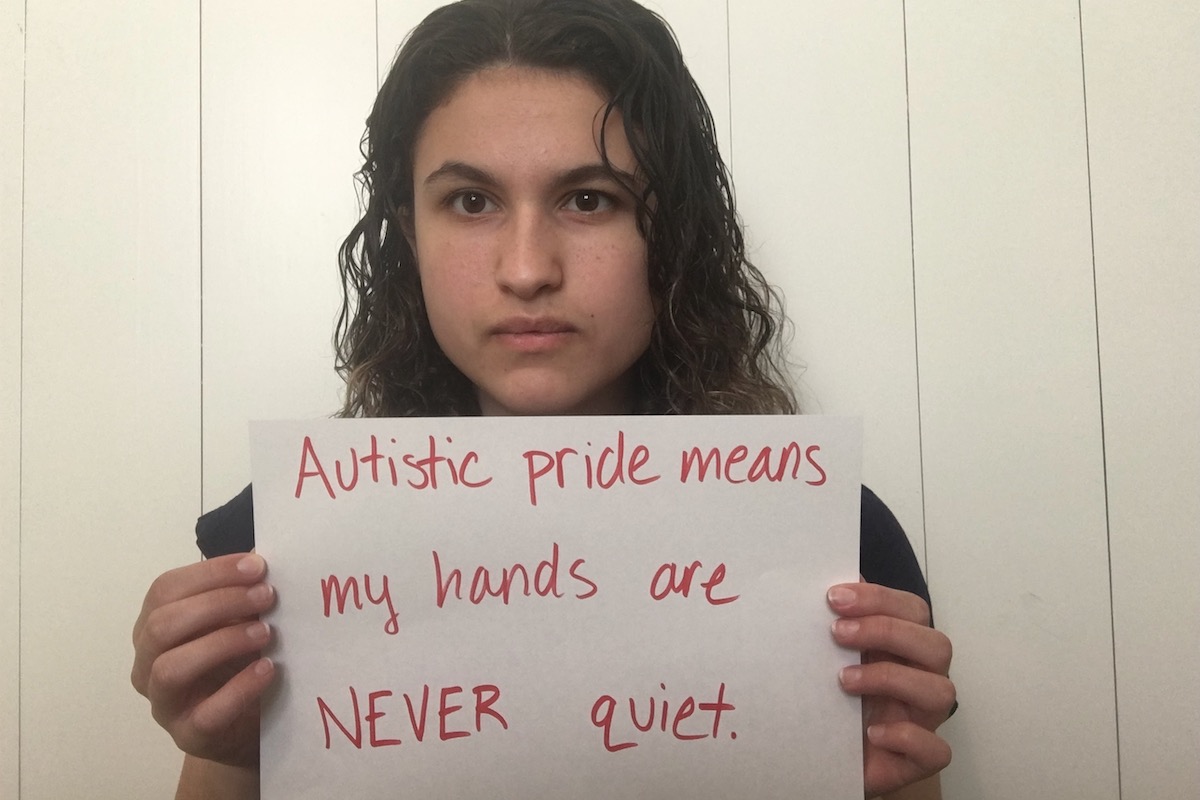

But no matter how hard I tried, I never achieved this state of normality. I didn’t even come close. My efforts to conform to these expectations left me exhausted and furious with myself, convinced of my own incompetence. The autism diagnosis had finally persuaded my parents and doctors that these goals were unattainable, and led me to the neurodiversity movement. There, I encountered the unexpected and exhilarating notion that autism was not a disorder to be treated, but a way of being to celebrate. You can’t fix what isn’t broken. Nothing about us without us. Autistic people are the real autism experts. These slogans gave me the confidence to embrace the parts of myself I had despised for so long. I realized that it wasn’t the end of the world if I didn’t want to make eye contact, that I could flap my hands during a lecture if I wanted to, I could rock back and forth as much as I liked, I could eat meals alone, go to bed early, and turn down party invitations. In short, I could be perpetually, decidedly atypical—and that was okay.

I could have stopped there, contenting myself with just enough disability theory to accept my own skills and limitations before moving on to other pursuits. But I didn’t. Maybe it was simply teenage self-absorption, motivated by narcissism. Maybe it had to do with the environment—Stanford’s obsession with “centering the marginalized” and “calling out the privileged.” Or maybe it was the memories of doctors who blamed me for my illness, medications prescribed against my will, the ensuing nightmares that left me dazed and sleepless, the panting, heaving animal fear that still rises in me whenever I hear sirens. For whatever reason, I continued to embrace increasingly radical iterations of the neurodiversity paradigm. I soon stumbled across the social model of disability, according to which, individuals are disabled not by medical conditions or specific diseases, but by a society that refuses to accommodate them. This theory neatly accounted for every painful experience of my past with just one word: ableism.

- Ableism: the psychiatrist who had shook his head in disgust as I curled on the couch in his office, refusing to speak. “You should try taking the books out of her room,” he told my parents. “There need to be consequences for negative behavior.”

- Ableism: my mother’s elbow at my shoulder when I was five, seven, 12, 15. “Eyes, Lucy. Eyes. Eyes. Look him in the eyes.”

- Ableism: lying spread-eagled in the examination room, the cold stethoscope pressing into the chasm beneath my breasts like an attack, an invasion.

- Ableism: the world against me, and me against the world.

This was my first intoxicating taste of empowerment born from victimhood. I was vindicated; exuberant. None of it had been my fault. All my doubts and self-hatred and guilt could be laid to rest. I had been the victim not only of circumstance and misfortune, but of oppression. The problem was simple, the solution equally so. I didn’t have to change—society did.

At the time, my new outlook seemed eminently rational, not to mention gratifying. I didn’t recognize that I had too much emotional stake in the game to perceive things objectively. The implicit dichotomy underlying the social model, which divides the world into victims and perpetrators of ableism, gave me a binary choice. I could notice the ways in which I was privileged, assigning myself to the dominant group, or I could continue to concentrate on my misfortunes, convincing myself that I was innocent and helpless. I would play a constant game of sorting the world into good and bad, dominant and dominated, oppressor and oppressed. I would drift further and further from objectivity. I would grow obsessed with the injustice I saw all around me. And I would label myself the victim every time.

I quickly learned to identify even the smallest traces of ableism in my surroundings. The personal was political, so I didn’t worry too much about poverty, abuse, or any of the other serious challenges disabled people face. Instead, I zeroed in on the minutiae: the word “stupid,” a building without elevators, an offensive headline on BuzzFeed. During my rhetorics class’s field trip to an art gallery, I scrutinized the building for evidence of ableism, triumphantly noting that the flashing lights in the exhibit may have triggered a seizure in a person with epilepsy. I don’t remember any of my other observations of the exhibit, nor do I recall the in-class discussion that followed. I was looking for injustice and I found it. QED.

Occasionally, I felt myself gravitating toward truth. I would read an article by an autistic person who did want to be cured or I would hear an argument in favor of behavioral treatment or I would realize, if only for a split second, that I am actually higher-functioning than many other autistics. And then I would recoil, frantically drowning my doubt in excuses and accusations. The author of that article had internalized their oppression. He was too brainwashed by Society-with-a-capital-S to know what he was talking about. Besides, how could I have forgotten the sanctity of my lived experience, my vow never to surrender to reason? Thus, I insulated myself from even the slightest traces of disagreement. Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words could force me to challenge my most dearly held beliefs and cope with the fact that I might be wrong—and that would be too much to bear.

* * *

The first week of March, I co-hosted a Disability Day of Mourning Vigil with Hillel at Stanford. I had gotten the idea from one of the many autism blogs I read regularly. Each year, the disability community came together in remembrance of people with disabilities who had been murdered by their caregivers. These are appalling crimes that tend to be taken far less seriously than killings of the non-disabled, which many advocates see as a symptom and consequence of widespread ableism. I spent weeks poring over speeches from previous vigils, scrolling through the names of the dead as I prepared to draft my own statement, which ended up endorsing a dystopian vision of unendurable oppression:

These murders are the product of a society that sees autistic people at best as high-functioning, and at worst, as violent, soulless, and less than human. Even when these beliefs aren’t expressed directly, they emerge constantly as the subtext in nearly every discussion of autism. As a society, we can’t allow these ideologies to flourish and then wonder why autistic people keep getting killed.

This speech sought to elucidate the causes of the deaths in question, but it said far more about my own psyche. By the time I delivered it, I saw a world dominated by an inescapable, sinister force that posed a threat to the very wellbeing of every disabled person, including me. As ominous as this tableau appears, it was also incredibly seductive. Who wouldn’t want to be the hero working to defeat such unthinkable evil? Living in fight mode was electrifying. Zealotry imbued my life with intensity, every moment brimming with vivid symbolism and apocalyptic meaning. I was on fire, and at the same time, I was fragile. I never would have admitted it, but I think that beneath all the slogans and bravado, I knew how precarious my worldview really was, how quickly it would collapse under scrutiny or rigorous analysis.

To ward off the ever-present threat of reason, I hid behind an ever-growing sense of defiant helplessness. I continued to extend my repertoire of victimhood, learning to soak up other people’s indignation and to nurture borrowed resentment. I had built my identity on the paradoxical symbiosis of empowerment and inability. My victimhood absolved me of agency and therefore, blame. Everything was someone else’s fault.

I spent spring break filming a seven-part series of sanctimonious videos in which I explained autism to unenlightened viewers. One segment involved an earnest evaluation of autism awareness products (“This keychain is incredibly offensive”), while another spoke sharply about the notion of treating autism (“We don’t want to be cured”). In a third, I railed against the assumption that some autistics were “low-functioning”: “One-third of the Autism Self Advocacy Network’s board members are nonspeaking, but they’re still in charge of an incredible organization, so please do not use functioning labels.”

My tone was terse, at once pleading and irritated. I was noticeably nervous. I wonder if I had considered the counterargument to what I was saying—that being on the board of such an organization necessitates a certain degree of cognitive ability that most autistics don’t have; that no amount of justification on my part would change the reality of their disabilities; that no one had appointed me as the spokeswoman of the disabled. If I was aware of such points, I did a good job of hiding it. “So, you know, please don’t call autism a disease,” I concluded, reaching out to shut off the camera. April had just begun. The death toll of the pandemic was rising, the economy was crashing, emergency rooms were overflowing, the disabled were facing care shortages and medical discrimination, and my greatest concern was semantics.

* * *

Mid-June, the academic year came to a premature halt in the wake of George Floyd’s death. I pored over lists of required reading for allies: 40 bail funds you should support, 120 brilliant YA novels by black authors, 3,934 things you can do to make up for your internalized white supremacy. I contemplated a major in Comparative Studies in Race and Ethnicity, signed petitions, and dutifully absorbed messages of self-hatred and complicity. I attended Stanford’s Black Lives Matter vigil, led by an organizer who added an unnecessary “s” to the term “folx” and wore a brittle, venomous expression. She began her remarks with a warning: “If you don’t feel comfortable here, you might ask yourself why that is—and whether you are part of the problem.” Her words stung, and I drank them in eagerly. I was there to repent. I took a certain perverse pleasure in self-flagellation. So, by way of atonement, I donated to bail funds, seduced by the reward of finding myself “on the right side of history.”

The last week of classes was more or less cancelled. “Go protest or something,” said our biology professor, abruptly concluding our final lecture. Summer heat settled in, thick and heavy. Any thoughts of autism advocacy were drowned out by my morally sanctioned self-hatred. I did everything I thought I was supposed to do—I downloaded podcasts and scrolled through articles and liked and shared and wondered what it would take for me to feel redeemed. The aspersions I had cast on others were coming back to bite me, and they were taking a toll on my sanity. I spiraled deeper into self-loathing, unable to shake the accusations of racism and bigotry from my mind, crippled by the guilt I had initially embraced. The harder I tried to atone, the more hopeless I became. “I just want to be a good person,” I texted a friend midway through June. “I’m just trying to educate myself about injustice. I don’t know if I can keep up. The bar just kept rising.” “Read this,” she responded, forwarding me a link to New Discourses.

I tell people that day marked the end of my activist career. I pored over James Lindsay’s writing before finding my way to a constellation of other sites, YouTube channels, podcasters, and writers I had never before considered. Every dissident thought that I’d learned to shove away over the years (“How can someone be a non-binary lesbian? What’s so bad about cultural appropriation? Must we make everything about race?”) returned, but now I realized that I could ask these questions and the world would keep turning. There was social justice outside of Social Justice—and perhaps less justice in it than I had assumed. I began to chart it all out on a giant sheet of butcher paper, trying to make sense of the insanity that had gripped me. I had developed a sense of infallibility that doubled as a defense mechanism, using false notions of “safety” and “aggression” to shelter myself from disagreement, unwilling to tolerate the dissonance that conflict might bring. I had built a sense of fragility through emotional reasoning and catastrophization, relishing my own loss of agency. In the process, I had moved further and further from reason, while deluding myself about the extent of my denial.

With all of this laid out before me, I could no longer ignore the fact that my obsession with justice hadn’t made me a good advocate; it had made me unbearable. My prolonged and pointless exercise in hubris had left me exhausted and miserable. It boiled down to this: did I want to keep living this way, or did I want to change? I chose the latter. I decided to stop fighting for justice, to swap vague and grandiose aspirations for the loose ends of everyday life. I no longer want to rid the world of ableism, but I do want to be kind to others and memorize Russian verbs and gain followers on my blog and return library books on time and get more people access to mental health first aid training and remember my friends’ birthdays and listen to indie rock and research psychosis and brush up on my French… and none of this fits into a neat dichotomy of right versus wrong or good versus evil.

I wanted to believe that my suffering could be explained by some sinister, ubiquitous force of oppression, but the truth is messier and less gratifying. There were no lurking demons or plots against me, just genetic misfortune and a broken healthcare system and well-meaning but ultimately unhelpful clinicians. I am neither hero nor villain. The understanding that most things aren’t about me, that at the end of the day, I don’t matter much, has come as both a disappointment and a relief. I’ve let go of the need to seek out constant verification that I am oppressed and disadvantaged. My sense of humor has returned. I’ve come to recognize the greatest irony of my forays into activism: In my quest to draw constant attention to my developmental abnormalities, I ended up acting in the most developmentally normal way possible.

There is nothing less unique than a teenage girl insisting that no one else in the entire world understands her. The more determined I was to resist inequality, the more I conformed, ceding my emotional stability to strangers on the Internet and uncritically parroting neurodiversity doctrine. Over recent months, in moving away from autism advocacy, I’ve rediscovered my sense of self. I am unafraid to speak my mind and stray from the crowd. I can be alone without feeling lonely. It certainly doesn’t take victimhood for me to know who I am, and I would rather demonstrate my character through action than stifle it with slogans.

Since the start of the summer, my existence has grown peaceful. I have many reasons for despair and many more for hope. The world went from an ideological war zone to a beautiful, flawed, wondrous place—and the only thing that changed was me.