Crime

How the Left Turned Words Into 'Violence,' and Violence Into 'Justice'

The idea that one’s disagreement with Ngo’s point of view disqualifies him from the physical protection granted to other ordinary citizens proved to be quite common in the aftermath of Ngo’s beating.

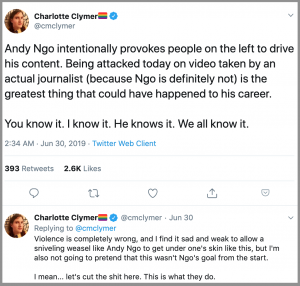

Responding to news that journalist Andy Ngo had been beaten by antifa protestors in Portland last month, a woman named Charlotte Clymer tweeted that “Ngo intentionally provokes people on the left to drive his content. Being attacked today on video taken by an actual journalist (because Ngo is definitely not) is the greatest thing that could have happened to his career. You know it. I know it. He knows it. We all know it. Violence is completely wrong, and I find it sad and weak to allow a sniveling weasel like Andy Ngo to get under one’s skin like this, but I’m also not going to pretend this wasn’t Ngo’s goal from the start. I mean, let’s cut the shit here. This is what they do.”

Who is Charlotte Clymer? She is an activist who works at the Human Rights Campaign, America’s “largest LGBTQ civil rights organization,” which supposedly “envision[s] a world where LGBTQ people are ensured equality at home, at work [and] in every community.” Andy Ngo, who has written for Quillette, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Post and other publications, happens to be gay. So this is where we are right now: A staffer for a human-rights organization dedicated to helping gay people is publicly cheering the beating of a gay man. This should raise an eyebrow.

The idea that one’s disagreement with Ngo’s point of view disqualifies him from the physical protection granted to other ordinary citizens proved to be quite common in the aftermath of Ngo’s beating. Aymann Ismall, a staff writer at Slate, for example, tweeted: “I’d argue what the fear mongering he’s done against Muslims plus the work he’s done to discredit hate crimes, helped create an atmosphere of violence that vulnerable people all have to live through just for being who they are. This is bad, but he’s guilty of worse.” Writer Jesse Singal, responding to this spate of violence apologism among Social Justice progressives, put it best with four words: “awful, awful, awful, awful.”

I’d argue what the fear mongering he’s done against Muslims plus the work he’s done to discredit hate crimes, helped create an atmosphere of violence that vulnerable people all have to live through just for being who they are. This is bad, but he’s guilty of worse.

— Aymann Ismail (@aymanndotcom) June 30, 2019

While this odd and unsettling reaction to Ngo’s beating may be dismissed by some as a passing reflex among radicalized culture warriors, it is actually well rooted in leftist academic social theory, which has blurred the distinction between word and action for decades. Under a prevalent view that has emerged from universities in recent years, a wrong opinion is seen as tantamount to a thrown punch or even an indication of a willingness to genocide—which invites the idea that an offended party who throws a real punch (or worse) is simply acting in self-defense. This idea has become so pervasive and is so taken-for-granted at this point that even workaday journalists now pay homage to this academic conceit in their work. In his account of the Portland violence, for instance, New York Times reporter Mike Baker summarized Ngo’s activities thusly:

Mr. Ngo is an independent journalist in the Portland area who works with the online magazine Quillette, a publication which prides itself on taking on ‘dangerous’ ideas…He has a history of battling with anti-fascist groups, with the two sides sharing a mutual antipathy that dates back many months. The conservative journalist has built a prominent presence in part by going into situations where there may be conflict and then publicizing the results.

The subtext is clear: Yes, Ngo got beaten. But c’mon—the guy had it coming.

In a recent episode of the podcast Other Life, an antifa member who is critical of the contemporary movement, Justin Murphy, noted that the blurring of the line between words and deeds is accomplished, to some extent, by creating a daisy chain of linkages, so that a person can be seen as an acceptable target merely because he is associated, in some way, with supposed “fascists.” (Though Murphy is highly critical of antifa’s methods, he still considers himself an antifa supporter, in the sense that he supports the idea of organizing against actual fascism.)

“The model [with antifa] would be, people look into someone like Andy Ngo, and—okay, maybe this guy has never said anything explicitly fascist, but—they look to see who he’s friends with; they look to see where he writes; and simply by virtue of not being within the kind of anti-fascist radical left milieu, that basically is incriminating,” Murphy said. “So the model there would be: this guy’s not particularly a fascist, but he supports—he basically enables fascism. Quillette enables fascism.” This should, perhaps, raise the other eyebrow.

These ideas aren’t new. In his influential 1961 book, The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon insisted that enemies of colonialism should resort to physical violence against their colonizers, both to effect political liberation and to improve their own mental health. Given the various forms of violence inherent to colonialism, this argument cannot be dismissed out of hand. But Fanon went further: He also wrote of the violence supposedly done by the words of colonizing elites as a spark for revolutionary activity.

This concept creep has been a mainstay of activist manuals ever since. It is evident, for example, in A. K. Thomson’s 2010 Black Bloc, White Riot, which praised “the dynamite Fanon would commit to paper.” Thomson sought to act out the moral logic of The Wretched of the Earth, while imagining the “white middle class” in the role of colonizers. Thomson’s declaration that “at the level of the individual, violence is a cleansing force” is itself an invitation to real violence. Moreover, he extended the idea of violence in a variety of obscure ways, including by larding up his tract with postmodern gibberish, as with the following passage: “Keeping with the ontological thrust of my argument, the conception of violence upon which this work is based presumes two fundamental and correlative attributes. First, violence is the name of the general principle by which objects are transformed through their relationship to other objects. Second (and as a result of the first), violence is both the precondition to politics and the premise upon which it rests.” Since “objects are transformed through their relationship to other objects” by means of deeds, words and thoughts alike, everything—or at least everything the radical left milieu rejects—is violence.

These ideas aren’t merely the gibbering of angry radicals. They have deep roots in leftist academic theory. In 1969, for instance, the Norwegian founder of “peace and conflict studies,” Johan Galtung, published an oft-cited piece titled Violence, Peace, and Peace Research, dedicated to the topic of “structural violence.” “When one husband beats his wife there is a clear case of personal violence,” he offered by way of example. “But when one million husbands keep one million wives in ignorance, there is structural violence.”

Structural violence, by definition, is something everyone participates in, even if it manifests only in the actions of a few, which are then treated as positive proof of the systemic problem that allowed those examples to be produced. We see this assumption and method, for example, in Cornell philosopher Kate Manne’s award-winning and highly praised 2017 book Down Girl: The Logic of Misogyny, wherein misogyny is redefined as a structural force that enforces patriarchy even if no one in particular holds any discriminatory beliefs. This thinking is no longer confined to the academic stratosphere: The crime of so-called “structural violence” was, in effect, the claim made against Ngo by Slate’s Aymann Ismall. The physical attack on the Portland reporter may have been “bad,” but the abstract harm caused by his structurally violent ideas supposedly is “worse.”

These ideas have proven to be so elastic that even the voicing of opposition to antifa itself can somehow be lumped in under the category of violence. As Murphy, the aforementioned antifa supporter, explains: “Any kind of cultural outlet that emerges in critical opposition to…the left-wing orthodoxy—well, the only reason they possibly could be doing that is because they want that left-wing orthodoxy to fail because they have ulterior motives of actually boosting and amplifying fascism, which they define as just whatever’s not the left-wing orthodoxy. So in this twisted worldview, someone like Andy Ngo is a genuine kind of accessory to fascism—even if you can’t find anything on record of him ever saying anything fascist.”

The means by which these fictional forms of violence can be perpetrated are myriad. Gender violence—a prominent subset of the idea of structural violence—arguably originated with Judith Butler’s 1990 landmark text Gender Trouble, and is described as a “violence of categorization.” Queer Theory, following significantly from Butler, accordingly indicates that a form of violence occurs when someone is categorized by sex, gender, or sexuality in a way they feel does not rightly describe them. So queer and trans activists now routinely claim that misgendering is inherently violent. In the words of actress Laverne Cox, “I have been saying for years that misgendering a trans person is an act of violence. When I say that I am referring to cultural and structural violence. The police misgendering and deadnaming trans murder victims as a matter of policy feels like a really good example of that cultural and structural violence.”

Much of this can be connected to the fixation on power relationships that infused many of the influential French thinkers of the Cold War period. In his 1979 book Distinction, French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu argued that a kind of symbolic violence occurs whenever social inequality is produced or maintained through “symbolic domination,” which itself is expressed whenever, say, someone is better dressed or better educated than those around him. And since these relationships are part of the world we live in, Bourdieu argued, violence is everywhere within the status quo. His long-time collaborator, sociologist Loïc Wacquant, highlighted the Marxist nature of this idea by arguing that “any capital, whatever the form it assumes, exerts a symbolic violence as soon as it is recognized, that is, misrecognized in its truth as capital and imposes itself as an authority calling for recognition.”

Of note, for Bourdieu, the relevant definition of capital is quite expansive: “Lifestyle is the foremost and perhaps today the most fundamental of these symbolic manifestations, clothing, furnishings, or any other property which, functioning according to the logic of membership and exclusion, makes differences in capital (understood as the capacity to appropriate scarce goods and the corresponding profits) visible under a form such that they escape the unjustifiable brutality of…pure violence, to accede to this form of misrecognized and [denied] violence, which is thereby asserted and recognized as legitimate, which is symbolic violence.” This 1978 passage is characteristically dense and difficult to understand. But the main idea—that “pure violence” is just a taboo subset of violence more generally, and that our system serves to whitewash these larger forms of “symbolic violence”—is well-reflected in the apologia offered on behalf of Andy Ngo’s antifa attackers.

Comb the literature, and you can find all sorts of adjectives tacked on to the word “violence.” This includes something called “discursive violence,” which was described in detail by scholars John Paul Jones, III, Heidi Nast and Susan Roberts in a 1997 volume titled Thresholds in Feminist Geography: Difference, Methodology, Representation. Discursivity, for their purposes, is defined “as those processes and practices through which statements are made, recorded, and legitimated through institutional and other means of linguistic circulation.” Thus, “discursive violence involves using these processes and practices to script groups or persons…in ways that counter how they would define themselves.”

It’s nearly certain, of course, that Ngo’s published articles on Islamism and antifa, both referenced in the wake of his beating, contained ideas and descriptions that “script groups of persons” in all sorts of controversial ways. But then again, that’s what all writers do—including everything that has been written about Ngo, and this article you are reading right now—since any text that challenges the presumptions of the reader will, in some way, fall under one of the broad categories offered by these scholars. Using such infinitely labile typology, all words can be theorized into violence so long as they have something to do with enforcing “domination” and “oppression,” so all real violence taken up in response to such words is self-defense.

Finally, we get to “epistemic violence,” the brain-child of postmodern Theorist Michel Foucault, who contended that violence is done by asserting power by creating, maintaining and participating in oppressive discourses. This concept is somewhat similar to discursive violence, and was developed considerably by postcolonial Theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak in the 1980s, who wrote on the ways in which the marginalized are prevented from being able to speak or have their knowledge considered real. This not only upholds a state in which marginalized people are not recognized as “knowers,” but also furthers the idea that they are unable to speak. (And, one should ask, if one cannot speak to achieve necessary change, what option is left to the silenced?) This idea has been extrapolated into the claim that media that do not reflect and proactively forward the point of view of marginalized voices are, in effect, inherently violent—a category that presumably would swallow up Quillette and a thousand other popular media outlets.

This development on Foucault’s idea, which was most famously put forth at the core of Spivak’s famous 1988 essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?” has been taken up by a wide swath of social-justice theorists, including black feminist epistemologist Kristie Dotson. By her further re-conception of epistemic violence, articulated in 2011, this form of violence is “the failure, owing to pernicious ignorance, of hearers to meet the vulnerabilities of speakers in linguistic exchanges.” Since this form of violence is embedded in the passive act of hearing, it not only takes the idea of violence out of the domain of action, but also out of the domain of speech—for Dotson seems to infer the existence of malicious intent within private mental processes, which she envisages as being akin to violence. In a word: thoughtcrime. (Some appreciation for this idea is manifested by those apologists for the beating of Andy Ngo who accused him of provoking antifa by failing to hear the ways in which they claimed his work made them feel “unsafe.”)

There is not a single scholar I have quoted who is not held in considerable esteem in influential sectors of academy to this day (A. K. Thomson should be regarded as an activist, and he’s unlikely to be held in any academic esteem). This is to say that the antifa cheerleaders offering excuses for the beating of Andy Ngo are not intellectual freelancers: Much of what they say would be received appreciatively were it expressed in the form of academic dissertation—or classroom discussion topic—in such fields as, say, gender studies, any critical constructivist approach to epistemology, or postcolonial studies. In this sense, both the barbarism in the streets observed in recently in Portland, and the shocking apologism that followed it, are the predictable result of decades of self-righteous political activism that became reinvented as supposedly legitimate forms of scholarship.