Top Stories

Can Public Shaming be Useful?

Just as coronavirus exposes the different fault lines and weaknesses of each society it invisibly penetrates, it has functioned as something of an exclamation mark upon a half-century of social and economic liberalism.

The pouted lip narcissism of youth was on full display in the front page pictures of Diana Lasu and Olivia Muranga. They were identified in the Australian newspaper Courier Mail last month after deceitfully returning to Queensland from Victoria carrying coronavirus. The young women were of African heritage, leading to some accusations of racism. Editors were quick to retort that those who committed crimes were regularly named.

Olivia Muranga was sick for days before she got tested for COVID-19. #9ACA https://t.co/NdLrHUjrrX

— A Current Affair (@ACurrentAffair9) August 2, 2020

The episode was a good example of shame’s comeback within the public health dominated morality we now share. Shame’s usefulness in codifying appropriate behaviour has become paramount.

The “subjective self interest” embodied by the convicted women in Queensland, cited in a British psychological study as predictive of poor compliance with behavioural restrictions, may especially require regulation through shame.

The term #Covidiot emerged online first as a hashtag. It has since been used thousands of times to criticise behaviour deemed errant, a marker of the rise of pandemic shaming.

Pandemic shaming has been used to expose drunk spring breakers flouting advice in America to those attending a large Stereophonics concert in Manchester. Public officials have been forced to resign after not living up to their own advice, including the chief medical officer of Scotland and Australian Minister Don Harwin exposed holidaying at his beach house in Australia.

Even wayward rugby league players, well known for scandals involving sex or violence, were termed Covidiots on the front page of Sydney’s Daily Telegraph after flouting health protocols.

While sidelined critics might argue tyranny describes the restrictions imposed by public health authorities, the priorities of such officials currently hold sway. Suddenly the acts of social distancing and appropriate hygiene have fallen into the realm of public law and order. Police prosecute those walking too closely or in excessively large groups. The act of targeted coughing is now a form of assault.

Epidemics have changed the course of history by reshaping our worlds, both physical and existential. Nothing compares to staring bald faced at our mortality when it comes to raising moral and philosophical issues.

Shame’s diffuse re-emergence in recent decades is a function of political tribalism reinforced by online information flows. Shame is a proxy for our relationship to groups, a moral language and with primitive emotions. It implies transgressions where we ascribe fault not just to an act, but also to the self, what is known in psychology as a global attribution.

The Left focused on those who transgressed boundaries of political correctness whereas the Right preferred targets like welfare fraud. Public health advocates had a greater tolerance for fat shaming or ostracising smokers. Meanwhile shaming associated with sexuality, its original iteration in the Biblical story of Adam and Eve, became increasingly rare.

Discussions around shame indicate a yearning for a moral language stripped bare from the decline of religion. We remain morally inarticulate and existential despair has been poached by the more medicalised language of mental health. The elevation of positivity has further stigmatised emotions like shame. Psychological studies have found that our culture fosters an unhealthy inability to tolerate negative emotions like anger, disgust, or shame contributing to a growth in disorders like self harm.

From a mental health point of view, there is an added urgency, being in the background of both the health and economic crises we face. Despite being one of the wealthiest countries, Australia still has the second highest rate of anti-depressant prescription after Iceland. The coronavirus has acted to prick a moment in Western civilisation which Israeli historian Yuval Harari calls a combination of incredible prosperity combined with a lack of purpose.

While there will undoubtedly be a rise in psychological ailments in the face of economic despair, many of my patients with anxiety disorders have not deteriorated. Their distress is no longer individualised but now shared. The socially anxious are also spared the performative strains of modern life in a service economy. These vary from the heightened focus on self presentation in the workplace to the scrutiny of chance encounters.

Just as coronavirus exposes the different fault lines and weaknesses of each society it invisibly penetrates, it has functioned as something of an exclamation mark upon a half-century of social and economic liberalism. If Brexit and Trump were initial portents, an epidemic that has stymied individual autonomy has potentially slammed a historical door. COVID-19 in its uncaring destruction has further highlighted Douglas Murray’s lament about modern liberalism and “the feeling that the story has run out”.

The language of individual rights is being smashed by the priorities of public health, which is dependent upon mutual obligation. Just as many national insurance programs received momentum after the Spanish flu, the emotional disconnection and dilution of group ties preceding the crisis may receive a much-needed tonic. The values of introspection, family, community, and renewed faith are likely to gain traction.

Within this context of a more united resistance against a collective threat, the usefulness of a gentle shame is being highlighted. This is especially true in a multicultural society where a focus on expressive individualism and self esteem will not translate for many ethnic groups.

According to anthropologist David Jordan, shame in Chinese cultures “is the ability to take delight in the performance of one’s duty.” Given Chinese and Indians dominate new migrants over the past decade, the stigmatisation of shame has implications for education and the law. Another example is domestic violence, which in ethnic communities has considerable overlaps with maintaining perceived honour. Alcohol and social disadvantage are stronger correlates in other demographics.

But recent outbreaks of pandemic shaming also expose the limitations. There is a tension between appropriate enforcement of acceptable behaviours and the trashing of individual dignity with no paths to forgiveness. This has been especially pronounced in the past decade through online shaming, where a host of figures both prominent and otherwise have been cancelled due to some kind of inappropriate action.

Healthy shaming involves a brief period of stigma combined with an associated ritual of re-integration. This is exactly what happens in group therapies for addiction or dieting, but cancel culture is narrowly about retribution. The combination of online activism and permanent marks on the Internet, shame’s digital shadow, also hamper the path of reintegration.

When discussing the world of social media, religious leaders have raised the prospect that without the concept of sin, our society lacks the structure to allow for forgiveness. The alternative is ostracism and exile without a route for reunion. Even groups such as those for weight loss or drug addiction contain aspects that incorporate Christian concepts of forgiveness.

In their academic research about the difference between shame and guilt American psychologists Tangney and Dearing give the predominant view in our culture: “Our lives as individuals, as social beings, and as a society can be enhanced by transforming painful, problematic feelings of shame into more adaptive feelings of guilt. Recognizing the distinction between shame and guilt is an important first step in making ours a more moral society.”

But our belief in the role of guilt as a superior emotion to regulate transgression is under threat with the declining role of Christianity’s moral axis of sin and redemption. Shame can be scaled which can be significant when behaviours are unacceptable but still within the law, especially when it comes to corporations or governments which are not capable of feeling guilt.

In her book Is Shame Necessary? environmental scientist Jennifer Jacquet writes:

Digital technologies have at once lowered the cost of gossip and exposure and expanded gossip’s speed and scope. This could make shame more salient to public life than ever before, especially since the power to use it has been put increasingly into the hands of citizens.

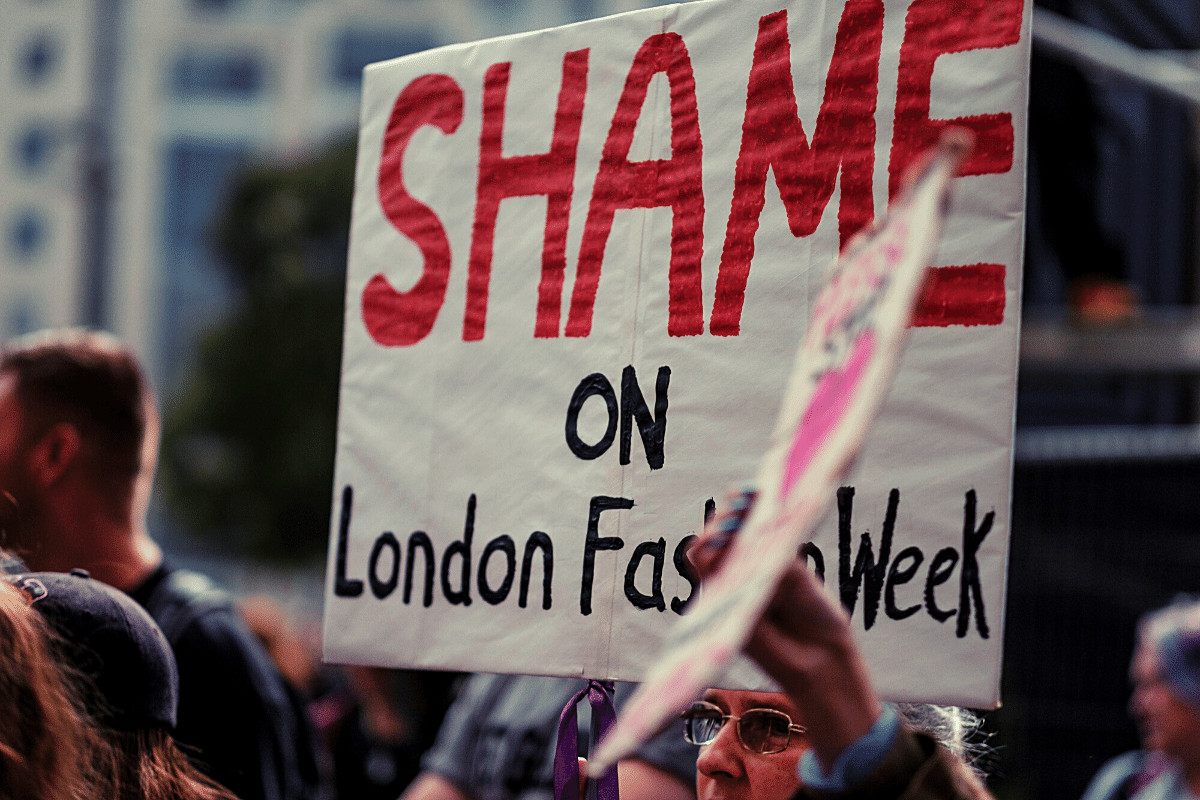

Jacquet cites the improvements in working conditions fashion companies were forced to undertake after global outcry when Dickensian, slave-like conditions were exposed through online shaming.

Western societies have underplayed the role of shame. Its utility has been deemed less relevant in a social milieu of greater diversity and urban anonymity. Shame requires an audience and a shared morality, something at odds with a multicultural society. We are ashamed of shame, portrayed instead as the inner demon responsible for a range of psychopathology.

Yet poorly understood shame is an unnamed undercurrent that leads people to avoidance and isolation. The emotion hides in plain sight while we pretend we have superseded it. As Salman Rushdie writes: “Dear Reader, shame is not the exclusive property of the East.”

What we often call social anxiety is steeped in shame, but one coloured by perceived failures in our media-rich meritocracy that breeds inadequacy. In the language of evolutionary psychology, we live an environment that encourages us into acts of social submission instead of grasping towards invitations of affiliation. Symptoms of emotional distress are often signals with regards to our perceived status within groups and hierarchies, many of which are now imagined online.

Our current circumstances are challenging us to renew our inner lives, just as we strive to avoid the threat to our physical bodies. The rise in the discussion of mental health in recent decades corresponds with a decline in a moral, metaphysical language. We increasingly lack a language for suffering and adversity.

Pandemic shaming is likely to be limited to this period whereby coronavirus is the dominant force shaping our lives. But its re-emergence is a pointer that shame has never really left, but just lurked with alternative names or iterations.

A better understanding of shame and a focus on its reintegrative potential offers promise to enliven our emotional selves.

In the wake of a shared threat to our species, we are bonded together in a mutual dread, imagining the implications for a better future. It is time for a kind of aggressive friendship to satisfy our longing for a richer collective, a lurch to greater affiliation.