Activism

Of Heroic Deeds and Hysterical Masses

Much of today’s madness results from the failure to impart that lesson, a failure in which those ostensible repositories of enlightenment (the nation’s institutions of higher learning), obstinately committed to inflaming self-pity and self-importance, are indisputably and indefensibly complicit.

Perpetual progress is no more possible than perpetual motion, an axiom unwittingly vindicated by the benighted throngs that currently run amok across America, menacing the living and long dead wherever they rage. Whereas in the final decade of the 19th century, “enlightenment had progressed to the point where the Salem trials were simply an embarrassing blot on the history of New England… [and] a reminder of how far the human race had come in two centuries,” in the second decade of the 21st, enlightenment’s decline has unleashed a new inquisitorial spirit, no less spurious than that of old. One only can hope that someday, the witch trials of our time will constitute an embarrassing blot on our history and that two centuries will not be needed for that day to arrive.

But at present, that is but a hope and in view of the unmitigated madness with which the present teems, a feeble one at that. What renders the hope all the more dim is that so much of the madness emanates from what ought to be repositories of enlightenment. Witness Princeton’s decision to strike Woodrow Wilson’s name from its School of Public and International Affairs—one more effort to correct the past, not by understanding and overcoming it, but by expunging it.

Wilson is not the sort of figure for whom I would take a stand, let alone a fall. (And I realize that in writing this, in effect I risk doing just that; that I set the stage for my own show trial.) There are ample reasons to be critical of the man, and not just because of his backward views on race, which were not exactly backward by the standards of his day and, besides, were more complex than the prevailing wisdom allows. But Wilson’s case does much to illuminate the reigning madness. (To historicize Wilson’s views is not to defend them. But historicizing them should serve to remind us of the obvious: that many positions espoused today will be considered backward in the future, the forward-thinking ones not least among them. Let it be lost on no one that Wilson belonged to, and was emblematic of, the era of Progressivism.)

Here we have one of the world’s top universities disassociating itself from one of its former presidents who, as the university’s current president concedes, did much to make Princeton what it is today. Princeton’s 13th president went on to become the nation’s 26th and is considered—or at least heretofore was considered—one of the better ones, boasting the sort of track record that should garner the approbation of liberals the nation over. This record includes (and I omit his successes in aggrandizing and bureaucratizing the state, which ipso facto also ought to please the Left): opposing colonial imperialism; championing national self-determination; devising the League of Nations (precursor to today’s United Nations); and winning a Nobel Peace Prize, the second US President to do so, and at a time no less when one had to accomplish something to earn one. That seems the sort of track record that would merit memorializing.

Lest there be any doubt that ours is an age of unreason, at this time when it is impermissible to honor the name of Woodrow Wilson, it is no more permissible to dishonor the name of George Floyd. Mind you, my aim here is to do neither. The tragic nature of Floyd’s death and Wilson’s support for segregation are so plainly established that they permit no quibbling. But upon whatever grounds the inviolability of Floyd’s name and irredeemability of Wilson’s repose, clearly they are not rational.

To this one might rejoin that Floyd has become a symbol. And to that one might rejoin, and therein lies the rub. Symbols tend to reveal as much as they conceal. Heroes themselves are symbols and heroes, like witches and the rest of us, have warts. When erecting a hero, the warts tend to get glossed over. They need not be ignored outright—scrubbed from the record—but it is self-defeating to magnify them. Perhaps there is no better way to tear down a hero than to expose that hero’s limitations; to show that he is, at bottom, human all too human and thus, no hero at all.

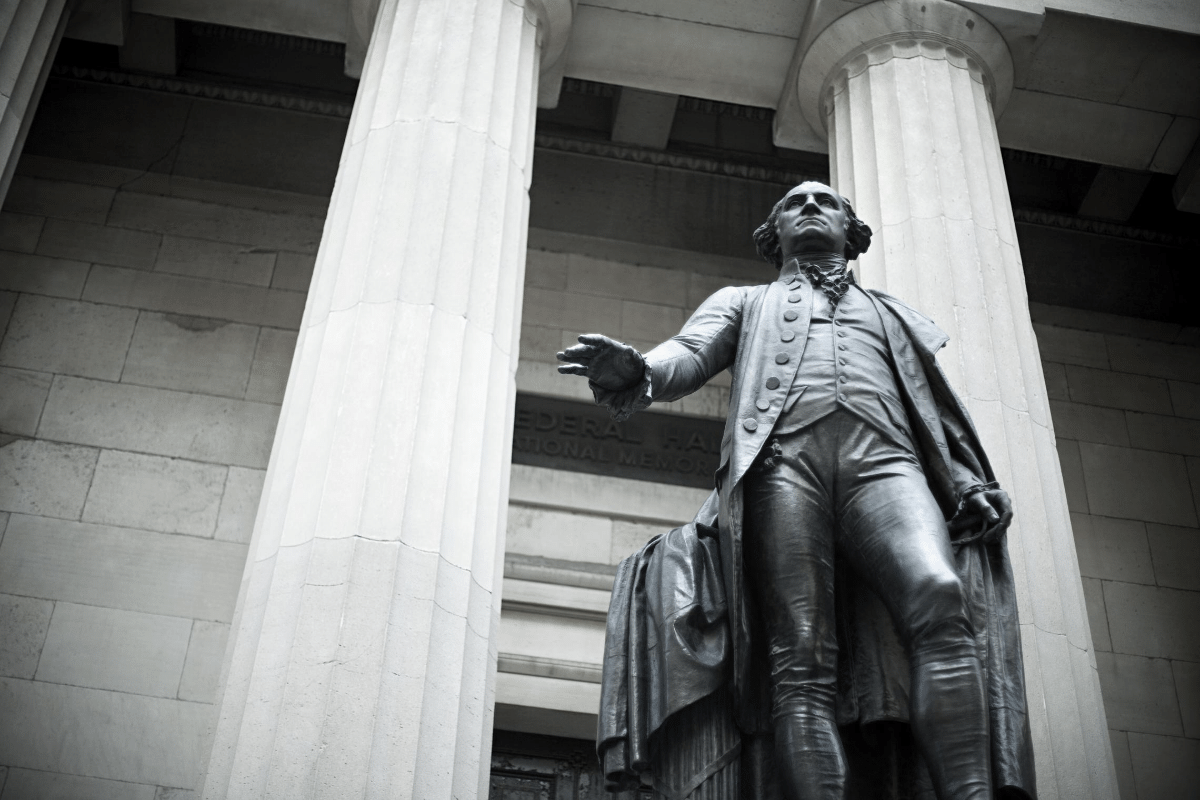

Washington, Jefferson: slaveowners. Jackson: slaveowner and Indian killer to boot. Teddy: incorrigible chauvinist and imperialist. FDR: presumptive anti-Semite. JFK, LBJ: womanizers. Clinton… well, you get the drift. But the question ought not to be is there anything tarnishable in people’s pasts—invariably there is—but does the magnitude of their misdeeds blot out the greatness of their heroic ones. That traditionally is what heroes have been made of—deeds. It is in part why, particularly in uncontemplative ages such as our own, heroes are men (and women) of action and not of letters. Interestingly and tellingly, Floyd’s heroic deed was being a victim of police brutality. At a time when victimhood has been elevated into a virtue, being a victim may be a necessary if not sufficient cause for heroism.

A judicious way to approach the matter would be to reflect on what you would have done or who you would have been in commensurate circumstances. The reality is—or was—that if you found yourself a wealthy, white landowner in the state of Virginia in the latter half of the 18th century, the odds were pretty high that you would have had slaves. And if you found yourself in that time and place but of African rather than British descent, odds are you would have had a master. In many ways, we are all but creatures of our time. Granted, Washington had more freedom not to be a slaveowner than William Lee had not to be a slave. But you likely delude yourself if you think you or the great majority of us would have behaved very differently. It might also be worth noting that if your skin color predisposed you toward being a slave it did not preclude you from owning one—or several. One other note, in the interest of perspective: what enabled people like Washington and Jefferson to own slaves was not so much their skin color but their wealth. If you were white in the antebellum south, odds are you would not have possessed a single slave, let alone many. Indeed, you very well may have opposed the peculiar institution, even if your reasons for doing so were not exactly high-minded.

But the owning of slaves is not what Washington is celebrated for and never was. It is a reflection of his human-all-too-human side, the side that we all share, the side that does not set heroes apart. But what of the other side; that side that prompted John Marshall to say of Washington that he was “first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen,” and that, in the absence of, the American experiment likely would have foundered before it ever really began? In the words of Mercy Otis Warren:

Had any character of less popularity and celebrity been designated to this high trust [the presidency], it might at this period have endangered, if not proved fatal to the peace of the union. Though some thought the executive vested with too great powers to be entrusted to the hand of any individual, Washington was an individual in whom they had the utmost confidence.

A poignant episode will permit us to appreciate how Washington earned the abiding confidence of his countrymen and became first in their hearts. At the close of the Revolutionary War, members of the Continental Army, rightfully disgruntled by their lack of pay and the general neglect they endured during the war, met in Newburgh (NY) to discuss the possibility of marching against Congress and fomenting an insurrection. Washington showed up unexpectedly and gave a speech—an exhortation to virtue—trying to allay his soldiers’ ire. The speech was not exactly well-received; the soldiers remained implacable.

Sensing this, Washington pulled from his pocket a letter from Congress that explained the financial straits the fledgling government then was weathering. As he struggled to read the small writing in which the letter had been inscribed, Washington pulled a pair of glasses from his coat pocket. Most of the soldiers were surprised by the revelation, having had no idea their general wore glasses. “Gentlemen,” said Washington, “you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country.”

As one major who was present recalled, “There was something so natural, so unaffected, in this appeal, as rendered it superior to the most studied oratory; it forced its way to the heart, and you might see sensibility moisten every eye.” The soldiers thanked Washington and asked him to intercede on their behalf. With an army at his command, a Caesarean seizure was well within Washington’s reach. But instead of marching on Philadelphia, he retired to Mount Vernon. It was an extraordinary moment, not only in American history, but in the annals of history—one that helps explain why the American people revered and trusted him as they did.

That is the sort of stuff that sets a man apart. In keeping with our more judicious approach to the past, we might ask how we would have behaved in those circumstances. Tabling the fact that just being in those circumstances would have required commanding a poorly outfit army of poorly trained rebels against one of the greatest military powers of the day over the course of a protracted conflict and surmounting tremendous adversity and odds to prosecute that effort successfully; that is, quelling the Newburgh Conspiracy presupposed a hero, it did not make one.

But setting all that aside, how would we have acted? We might be inclined to comfort ourselves and say that we would have behaved as Washington did. And perhaps we would have. The lessons of history suggest otherwise; that we would have been more likely to wield the power at our disposal than relinquish it. But if it is the benefit of the doubt you seek, consider it granted. However that benefit cannot be granted to the incipient despots who tear down statues and petulantly demand that present and past conform to their vision of social justice. There can be no doubt how they would have behaved in light of how they do behave with what little power they possess. Their mettle is the stuff of mobs not heroes. They are fit to destroy a nation not found one.

Like heroes, witches, and the rest of us, nations are flawed. A nation without injustice is like a man without sin—not of this world. That was the dream of 19th-century socialist utopians, a dream responsible for so many of the 20th century’s horrors to which far too many in the 21st century remain inveterately obtuse. The purity that utopians demand, a demand echoed by the perpetually aggrieved crusaders of today, betrays a want of measure that a meaningful understanding of the past would do much to alleviate. As David McCullough so admirably put it, “A sense of history is an antidote to self-pity and self-importance, of which there is much too much in our time. To a large degree, history is a lesson in proportions.”

Much of today’s madness results from the failure to impart that lesson, a failure in which those ostensible repositories of enlightenment (the nation’s institutions of higher learning), obstinately committed to inflaming self-pity and self-importance, are indisputably and indefensibly complicit. It is not a moral compass that America lacks, far from it; rather, it is a sense of history and proportion with it. Not the least disconcerting aspect of our times is that history is being rewritten by those who grasp so little of it. If left unchecked, it is not only the past that will be lost, but the future too.