Top Stories

Is Woke Capitalism Profitable?

When done correctly, woke capitalism functions as a form of costless virtue signalling.

In your foray through the culture wars, you’ve likely come across the term “woke capitalism.” Or the associated adage “get woke, go broke.”

A term popularised by New York Times columnist Ross Douthat, woke capitalism refers to a clever ploy where corporations pay homage to the cultural Left in return for leniency when fulfilling their primary objective: making money. In short, a company’s exaltation of progressive social causes yields temporary protection from the activist Left. As for “get woke, go broke,” the concept is simple: support progressive causes, lose money.

While these concepts make intuitive sense, they haven’t been thoroughly researched. The problem with the culture wars isn’t its divisiveness. That’s par for the course. The problem is its lack of empirical rigour. How much of what we see on social media is verifiably true? Then again, if no one actively researches these concepts, how would we know?

The hyper-partisanship which characterizes the culture wars lends itself to the promotion of unsubstantiated claims and the shoehorning of single datapoints to fit narratives. Victory at the cost of truth.

Here, I use quantitative research methods to get to the bottom of woke capitalism. In short, my aim is to answer one question: Is woke capitalism profitable or does “get woke, go broke” hold true?

Statistics without tears (hopefully)

In designing this project, it was important to select a research method that answered my question but wasn’t so convoluted or mathematically dense that it bored you.

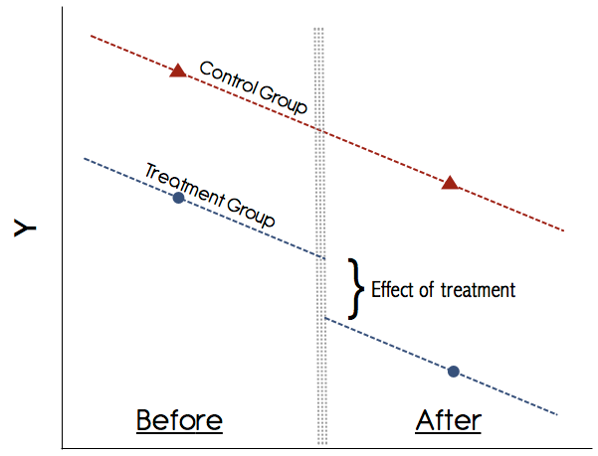

When testing the effect of a clinical intervention or policy change, researchers will often employ a randomized control trial (RCT). This involves randomly allocating participants into two groups: one that receives the intervention (treatment group) and one that does not (control group). Randomization minimizes selection biases and confounding variables, allowing the control and treatment groups to be as similar as possible. We then test the impact of the intervention by measuring how much the groups differ based on an outcome variable.

However, when it comes to measuring the effect of woke capitalism, this sort of research design just isn’t feasible. The logistical and ethical constraints are too numerous. Fortunately, there are other options.

To answer this question, I used econometric modelling. Econometrics involves the use of statistical and mathematical models to quantify economic phenomena. In plain English, it’s the subtle art of using fancy stats “to sift through mountains of data to extract simple relationships.” In this regard, I’ve designed a difference-in-differences (DID) model to test the effect of woke capitalism on stock prices.

DID calculates the difference in outcomes between the treatment and control groups before the intervention (pre-intervention period) and the difference in outcomes after the intervention (post-intervention period). The difference between those two differences is the estimated treatment effect (impact) of the intervention. Hence the name, difference-in-differences.

For this study, I gathered two years of data on stock prices for six companies: Starbucks, Dunkin’, Nike, Adidas, Delta Air Lines, and American Airlines. Three companies, Starbucks, Nike, and Delta, make up the treatment group as they implemented a woke policy. Dunkin’, Adidas, and American Airlines make up the control group as they are intra-industry competitors that did not implement a similar policy during the same period.

To be clear, companies in the treatment group were selected based on the popularity of their woke stance. In May 2018, Starbucks changed its bathroom policy to allow public use of its facilities. This came in response to an incident at a Philadelphia Starbucks where police were called on two black men who were occupying a table but did not make a purchase. 2018 also marked the year that Nike launched its social justice-themed ad campaign featuring former-NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick who famously kneeled during the American national anthem. Finally, in February 2018, Delta ended its discount program for Nation Rifle Association (NRA) members in response to the Parkland shooting.

The DID model measures the extent to which the treatment group’s participation in woke capitalism affected its stock price relative to the control group. Closing prices for the treatment and control groups were organized into 105 weeks. Weeks -52 to -1 reflect the weeks leading up to the woke intervention, week 0 reflects the week of the intervention, and weeks 1 to 52 reflect the weeks following the intervention. Doing so allows for week-specific estimates of the effect of woke capitalism on the stock price. Finally, I set week -1 as the reference period to estimate week-specific effects.

This study is not without limitations, however. While DID represents a feasible way to learn about causal relationships, it is not a perfect substitute for RCTs. Secondly, given its volatility, stock prices are difficult to model without data on a retinue of variables relating to the overall market and the stock itself. As such, factors which might contribute to the rise and fall of a stock could not be controlled for.

Here’s what I found

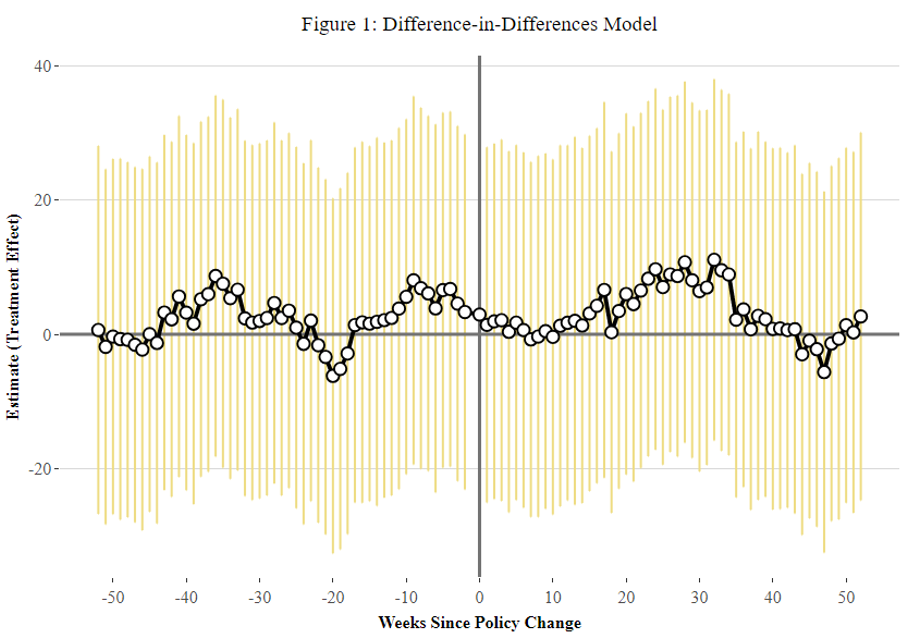

Figure 1 presents the results of the DID model. This visualization reports the estimates of the intervention with 95 percent confidence intervals. The woke intervention was centred at week 0, with values on the x-axis reflecting the weeks since the intervention occurred.

The estimates (the white dots) reflect the amount (measured in US dollars) the share price increased or decreased when the treatment and control groups are measured against one another. Importantly, the confidence intervals (the yellow lines emanating from the white dots) reflect the range of plausible values that the estimate can fall between. Statisticians use confidence intervals to measure uncertainty. The wider the confidence interval, the less certain we are about the exact estimate. While a wide confidence interval usually means that the sample size was too small, this does not mean that the results are necessarily “wrong,” just inconclusive.

Based on the DID model, woke capitalism does not appear to have a demonstrable impact on share prices. More specifically, the model isn’t very informative as the confidence intervals for all estimates are very wide. Put plainly, the model is functionally inept as it tells us nothing about the impact of woke capitalism.

But while the DID model offers no real insight into the effect of woke capitalism on share prices, it does reveal an important detail: There is more at play here than just wokeness. A closer look at the share prices of each company reveals this.

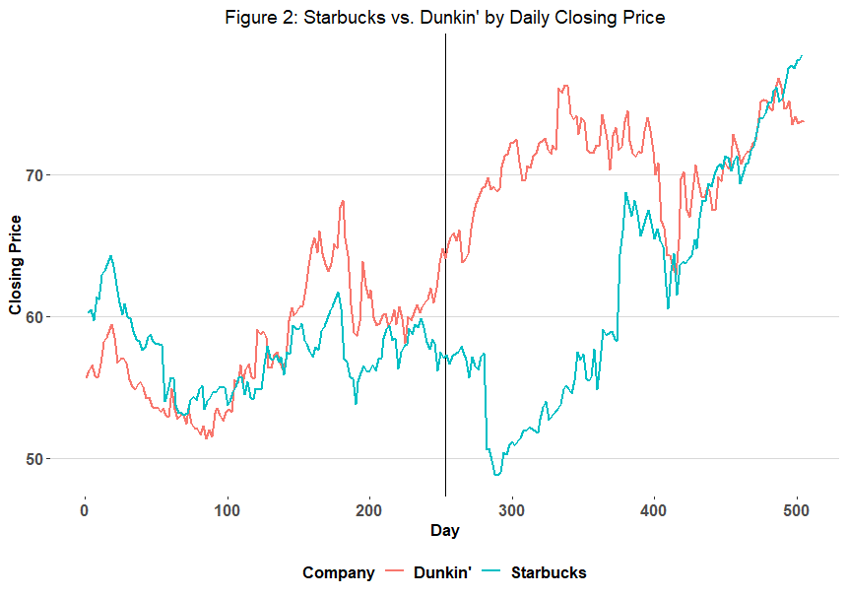

Upon closer examination, Starbucks’s open-bathroom policy likely had little to no effect on its share price in the interim or long term (see figure 2). In the 27 days following the policy change, Starbucks had an average one-day return of -0.0096 percent, indicating a great level of price stability. Moreover, in the 27 days prior to the policy change, the average one-day return was 0.062 percent. These are comparable rates.

However, one might notice a substantial dip in Starbucks’s share price immediately following the policy change. This reflects nine and three percent declines in one-day returns on June 20th and 21st of 2018.

Despite being relatively close to the intervention date, these declines do not reflect the policy change. On June 19th, Starbucks CEO Kevin Johnson announced that the company would both decelerate the number of licensed store openings and close more than 150 stores in 2019. These decisions reflect Starbucks’s desire to focus more on its loyalty program, mobile app, and refreshment drinks. Importantly, Starbucks’s share prices rose steadily following this decline, experiencing an average one-day return of 0.2 percent between June 22nd, 2018 and May 10th, 2019. Nevertheless, these developments must be paired with stable increases in Dunkin’s share price.

Is it possible that Starbucks’s policy change hamstrung its growth while Dunkin’s lack of a similar policy change allowed it to grow unimpeded? This is possible, but unlikely. Dunkin’s share price was climbing long before the policy change, averaging a 0.3 percent average one-day return in the 20 days leading up to the intervention. Compare this to the 0.26, 0.25, and 0.12 percent average one-day returns in the respective 20, 50, and 100 days following Starbucks’s policy change. In fact, Dunkin’s stock price has more than doubled in the long term, climbing from $39.40 in January 2016 to $80.90 in August 2019.

This, however, is not to suggest that Starbucks has escaped completely unscathed. While profits increased in 2018 and 2019, monthly foot traffic in select Starbucks has declined by 6.8 percent compared to other nearby coffee shops following the policy change. More specifically, customer foot traffic declined at almost twice the rate at Starbucks closest to homeless shelters than those farthest away. All told, customers are spending five percent less time in Starbucks restaurants.

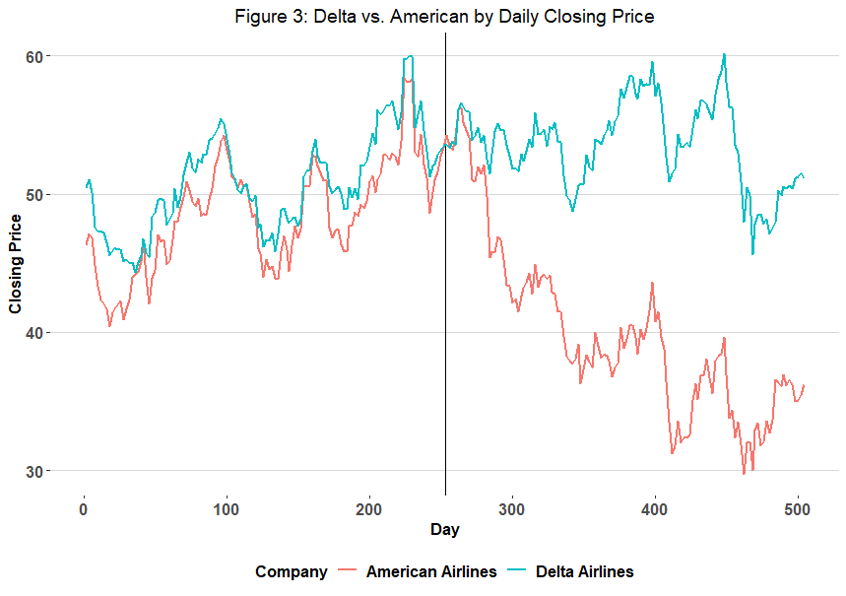

Like Starbucks, Delta’s cancellation of its NRA discount plan had little effect on its stock price relative to American’s (see figure 3). To this extent, Delta’s share price remained relatively stable, with average one-day returns of 0.04, -0.07, -0.02, 0.05, 0.02, and -0.03 percent in the respective 20, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 253 days since cancelling its NRA discount plan. Compare this to the -0.1, -0.02, 0.12, 0.02, 0.05, and 0.04 percent average one-day returns in the respective 20, 50, 100, 150, 200, and 253 days before the cancellation. In short, this policy change did little to affect Delta’s share price in the short and long term.

In comparison, American Airlines had an average one-day return of -0.2 percent over the entire post-treatment period, with its share price falling 37 percent.

But is this decline a result of American’s failure to cancel its own NRA discount plan? This is unlikely. American Airlines never had an NRA discount plan to begin with. Moreover, American’s 50 percent price drop from January 2019 to August 2019 is largely attributed to rising oil prices during that period. Rising oil prices force airlines to pay more for jet fuel. These costs are then passed down to passengers who are less likely to fly if ticket prices are too high.

But shouldn’t this have also affected Delta? Not necessarily.

Unlike other airlines, Delta owns an oil refinery which supplies a quarter of its fuel needs—saving the company 0.07 cents per gallon. Furthermore, any additional fuel costs may have been offset by Delta’s industry-leading on-time arrival rate and 98 percent reduction in maintenance cancellations. Delta owned the highest customer satisfaction rating in 2017 and 2018 among airlines. In comparison, American Airlines has suffered a spate of maintenance cancellations and is cash flow negative following its purchase of a fleet of fuel-efficient planes.

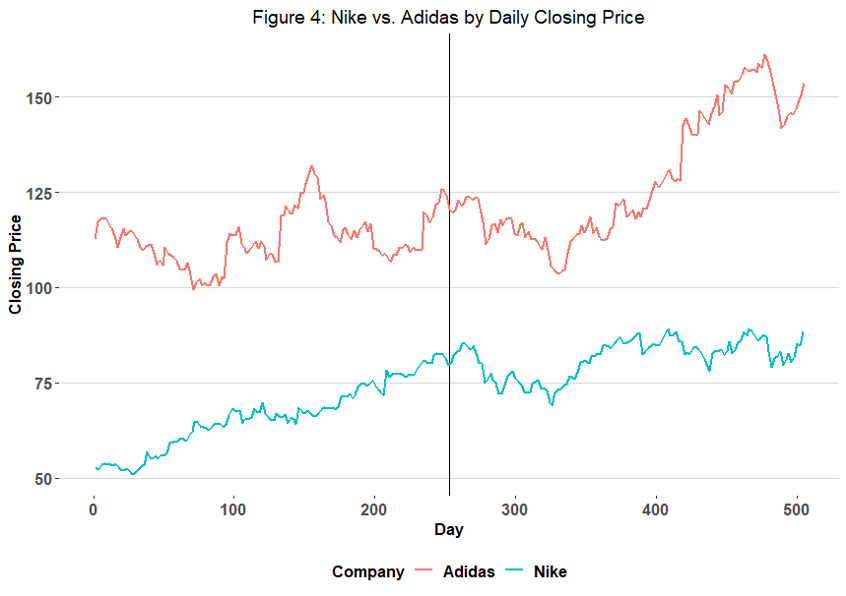

When it comes to Nike, the Kaepernick ad campaign did little to improve its performance against Adidas (see figure 4). While Nike had a higher average one-day return (0.17 percent) than Adidas (0.05 percent) in the pre-treatment period, Adidas (0.11 percent) outperformed Nike (0.06 percent) in the post-treatment period.

However, the ad campaign did improve Nike’s share prices immediately following launch. While Nike’s average one-day return was -0.04 percent in the 15 days leading up to ad launch, it was 0.3 percent in the 15 days after launch. In fact, between September 2nd and September 4th, Nike’s online sales grew by 31 percent. Moreover, Nike shares surged 36 percent during that year, making the company the top performer on the Dow’s index of 30 blue-chip stocks.

But what does this all mean? Is woke capitalism profitable or does “get woke, go broke” hold true? Based on these findings, woke corporate policies do little to positively or negatively impact a company’s bottom line. While financial gains are possible, they are minimal. In other words, woke capitalism is, for the most part, financially inconsequential relative to other higher order factors, be they store closures or increased production costs. The market is the market. It is unpredictable, volatile, and based on trillions of hard-to-model data points. As such, woke capitalism doesn’t move the needle. Going woke won’t make you broke, but it won’t line your pockets either.

However, this raises a more interesting question: Why would a company make a business decision that bore no impact on its bottom line?

Demography is destiny

In every industry or institution there exists a metagame. These are hidden yet fundamental stratagems that transcend the conventional rules of the game. Be they uncanny, unconventional, or counterintuitive—these processes amount to specialized knowledge about how the “game” should be played. Mastery of the metagame confers success and strategic dominance, separating those who win bigly from those who just get by. It is the metagame which separates the Peter Thiels of the world from Joe Shmoe.

Given the pervasiveness of the culture wars, corporations that successfully engage in woke capitalism are playing the metagame. That is to say, they understand something that Joe Shmoe does not: Consumer demographics matter.

When it comes to the culture wars, the goal of a corporation is not to maximize profits, but to minimize losses. Given their profit-driven nature, corporations are, by default, targets of the activist Left. For them, going woke is a strategic decision to appease those who would otherwise destroy them with taxes and boycotts. As such, woke capitalism is corporate conservationism. It is a fiscal stay-of-execution from the profit-killing axe of the activist Left. But the metagame behind woke capitalism is more nuanced than this.

A company’s decision to “go woke” is also driven by knowledge of who its customers are and what causes they support. The importance of consumer demographics is nothing new, but it has become even more important in today’s cultural climate. Consumers are increasingly supportive of corporations that pedal their preferred social causes.

According to a Sprout Social survey of 1,000 US consumers, 66 percent of respondents said it was “important for brands to take public stands on social and political issues.” In fact, 78 percent of liberals and 52 percent of conservatives agreed with this. But it’s not just political partisans. One report found that 58 percent of millennials, 55 percent of Gen Xers, and 51 percent of baby boomers wanted brands to invest in causes they cared about.

However, the most staggering numbers come from a 2018 Edelman report where more respondents trusted businesses (48 percent) than they did government (33 percent). In fact, 53 percent believed that brands could do more to solve social ills than government. Interestingly, 64 percent of respondents were belief-driven buyers, agreeing with the statement “I believe brands can be a powerful force for change. I expect them to represent me and solve societal problems. My wallet is my vote.”

Given these statistics, it is understandable why corporations have become outspoken defenders of progressive social causes. Political apathy is death. And a corporation’s decision to engage in woke capitalism hinges on what certain consumers can and can’t tolerate. Consider the three companies that made up our treatment group.

Starbucks’s primary target demographic are young, urban, affluent, on-the-go, white-collar professionals. To be more specific, 40 and 49 percent of Starbucks’s yearly revenue comes from customers between the ages of 18 and 24 and 25 and 40, respectively. In fact, here are several statistics that paint a clearer picture about who sips lattes at Starbucks. Forty-five percent of Starbucks’s customers do not have a religious preference, 80 percent have an active presence on social media, 52 percent are not parents, 25 percent purchase organic foods, 51 percent are willing to embrace “creative” solutions to problems facing the US, and 46 percent often make decisions based on their emotions.

Suffice it to say, the average Starbucks customer probably isn’t voting for Trump in November. More importantly, they are the demographic most likely to support woke corporate stances. Consider the political views of American millennials, Starbucks’s primary age demographic.

According to Pew Research, millennials are the only generation in which a majority (57 percent) holds consistently liberal or mostly liberal positions. To this extent, 52 percent of millennials believed that racial discrimination is the reason why blacks can’t get ahead, 79 percent believed that immigrants did more to strengthen the country than harm it, 57 percent favoured larger government, 66 percent believed the current economic system unfairly favoured the powerful, and 72 percent opposed building a border wall along the US-Mexico border.

As such, Starbucks’s decision to change its bathroom policy in support of racial justice is a low-cost stratagem that plays to the values of its customers. Moreover, it placates the activist Left by signalling a willingness to “do better.” Starbucks was playing the metagame.

We also see this with Nike. Nike’s primary target demographic skews particularly young, with those between the ages of 18 and 34 constituting 43 percent of Nike’s customers. Moreover, Asians, Hispanics, and Blacks, who account for three, 16 and 13 percent of the American population, represent five, 19, and 18 percent of Nike’s consumer base, respectively. In fact, Nike’s customers are seven percent less likely to vote Republican.

As you might imagine, Nike’s consumer base likely favoured the Kaepernick ad campaign. Consider how Americans in the same race and age brackets viewed professional athletes kneeling for the American national anthem. According to Pew Research, 61 percent of Gen Zers and 62 percent of millennials approved of NFL players kneeling. Furthermore, a Post-Kaiser survey revealed that 66 and 69 percent of Democrats and Blacks approved of the protests, respectively.

However, when one considers how Nike’s sales strategy operates, the brilliance of the Kaepernick ad campaign becomes apparent. Nike’s best customer prospects are active, high-earning young people that reside in big cities. Big cities are test markets where companies can determine the staying power of new styles, designs, and political stances. These dense urban zones are also hotbeds for progressive politics. For Nike, the woke metagame revolved around playing to the politics of its millennial consumer base that resided in major urban zones. The result was 20, 14, 10, and nine percent sales increases in Seattle, San Jose, San Francisco, and New York from September 3rd to September 12th, respectively.

For Delta, the metagame was far simpler. The airline’s discount contract for NRA members only sold 13 tickets. In cancelling it, Delta wasn’t giving up much. There would be no consumer backlash. Furthermore, Delta’s $40 million jet fuel tax break in Georgia was reinstated despite its earlier suspension by Republicans.

When done correctly, woke capitalism functions as a form of costless virtue signalling. The activist Left is placated, and customers are reassured of a company’s commitment to corporate social responsibility. Of course, failing to understand consumer demographics or overemphasizing one’s progressive bona fides to the point of disingenuity can be disastrous. Gillette’s “We Believe” and Pepsi’s “Live for Now” ads are proof of this. Woke capitalism requires careful research and a light touch.

What a loser

While the stated aim of this project was to better understand woke capitalism, the overarching objective was to expose the empirical frailty of the culture wars. Cultural warriors have a habit of oversimplifying complex phenomena. The result is catchy slogans and dank memes.

In fact, much of how the culture wars are waged is intimately tied to what Dilbert creator, Scott Adams, calls “loserthink.” For Adams, loserthink amounts to techniques that permit us to make errors in judgment. Be it Occam’s razor, relying on anecdotal evidence, or ignoring relevant context, loserthink is part and parcel to the culture wars.

To be clear, this isn’t to suggest that culture warriors are dumb or uninformed. Granted, some are just plain annoying. It’s more so that much of what they claim to be true isn’t so. If our aim is to have a discussion about big ideas, the first step is to determine what is factual and what is not. For the toxicity of the culture wars to be mitigated, truth must come before tribalism.

Acknowledgements and notes

- A special thank you to Dr. John MacDonald for his sage advice on DID.

- DID model: R2 = 0.12

- Statistical analysis and data visualization were done in R. Data cleaning and preparation were done in Python and Microsoft Excel.

- I declare no conflicts of interest. I am in no way affiliated with any of the companies examined.