Bernard Rose

Bernard Rose's Forgotten Tolstoy Trilogy

This is the least operatic, and most touching, of the trilogy.

Much has been made in the press of surging sales during lockdown of “bucket list” classics such as Anna Karenina and War and Peace. One Brooklyn journal, A Public Space, has started a group called “Tolstoy Together” so that readers can urge each other on through his doorstep novels at the rate of about 12–15 pages a day. Tolstoy, it seems, is one of those writers we reach instinctively for in times of crisis. His capacious books and their themes of love, death, human conflict, and above all how to live and to find meaning, provide the kind of reading experience that is not so much escape from life as confrontation with it. But how many of those with less stamina or time on their hands have considered watching the Tolstoy films of the British director Bernard Rose?

I would not include in these Rose’s 1997 adaptation of Anna Karenina, deemed a flop by its critics, not least the director himself, who was effectively banned from the cutting room as the studio hacked off half an hour. A “travesty of the novel” that “deserves to be put in the trash” was how Rose later described his film, adding in another interview that it was almost impossible to film the 864-page novel without turning it into a conventional love story, which it isn’t. It was in the wake of this turkey, he said, and “partly as an apology to Tolstoy,” that he turned to Tolstoy’s slimmer works, basing a series of independent films on his novellas and short stories, starting with The Death of Ivan Ilyich (1886), filmed as Ivans XTC in 2000, and due to celebrate its 20th birthday in September of this year.

Rose’s project was to update the stories about 19th-century Russia to contemporary American settings while staying true to the shape and spirit of the original. “What’s great about Tolstoy,” he said in interview, “is that he asks the big questions. The existential, spiritual and emotional questions, and he really tries to answer them. None of those questions have been resolved by us in the slightest. We’re still dealing with the same things.”

The Death of Ivan Ilyich tells the story of a man of position dying and realising that his life, hitherto so correct to him, has had little truth or meaning, and Ivans XTC does the same. Rose’s conceit was to set it in 90s Hollywood, and to make it about a talent agent. In place of Ivan Ilyich’s rise in the civil service, his provincial social climbing and fraught travesty of a marriage, we have the world of pre-#Metoo Hollywood, snorting, fucking, and cheek-clashing its way to perdition. We follow the last week in the life of Ivan Beckman, the charismatic agent on-the-up who charms everyone he meets with his smile, wit, and an almost balletic lightness of social touch.

Ivan’s a promiscuous cokehead with a promiscuous cokehead girlfriend, but he’s very good at his job. So successful is he at poaching a major star from a rival agency (an enjoyably reptilian Peter Weller), that he’s rewarded with a love-bombing by his own. Yet shortly afterwards, on the news of his death, those same people, after a few seconds of pious silence, instantly snap into action, jockeying for position and trying to ensure their late colleague’s clients don’t jump ship. One of Ivan’s running-mates declares him posthumously a “drug-addict and a pussy freak” and his funeral turns into a farce—industry-bickering across the pews drowning out the eulogy. It is, it turns out, a fitting memorial. Ivan, loved, courted, and feted by everyone, seems to have had no real friends at all, bar a golden retriever and the family who had warned him that in his profession he “would drown.”

None of this, to the dying Ivan, would come as much surprise. There is a moment where, caught on strobe at a sex-party, he stares at the camera as though begging us to rescue him. “Last night I had this incredible pain,” he tells a couple of prostitutes he later invites over for company. “The pain was so strong that I took every pill in the goddamn house. The pills… wouldn’t do anything. The pain wouldn’t go away. I tried to find one image, one worthwhile image, that would get me through it. And all I could find was shit.” The prostitutes stare at him mortified, with “too-much-information” rictus smiles, then scarper.

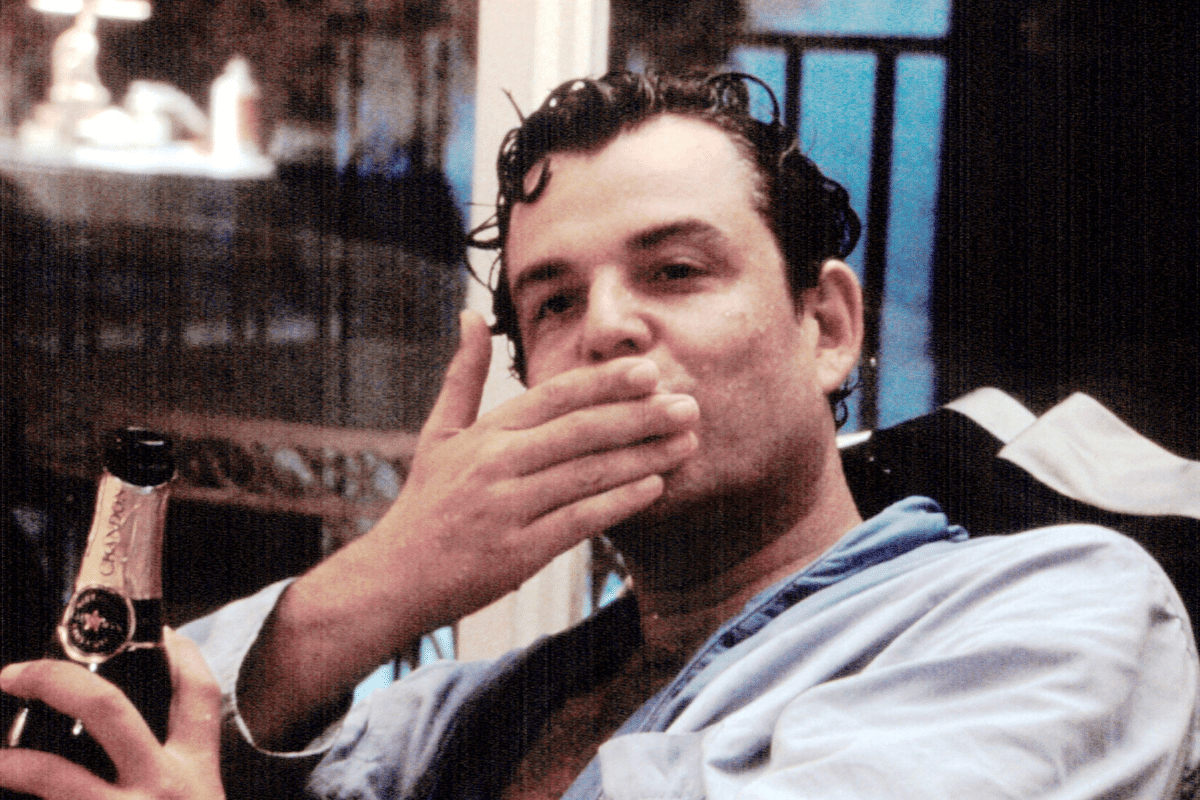

Ivans XTC is a compelling if slightly chilly film, though it’s lit up by an indelible central performance from Danny Huston (son of the late John), near-unknown before the film came out. Huston is endlessly watchable, able to suggest both urbanity and a haunted, little-boy-lost quality, an actor charismatic enough, Rose said, for viewers to surrender themselves to the journey with him. He charms, confides, opens up, and covers up, always at an ironic distance from the world he inhabits. Ivan’s colleagues may not love him, but we certainly do, and the film’s impact will depend on how much you believe such a seductive character could command so little loyalty from his peers.

Ivans XTC was a pioneering film, made on the lowest of budgets with new digital technology which liberated film-makers from studio funding. “We didn’t have to ask anyone’s permission,” said Huston. “We were like a sort of punk band.” It was, perhaps, a film before its time; in the wake of #Metoo, its unflinching picture of Hollywood sleaze would have found its moment. As it was, the film had poor timing, due for release shortly after the tragic suicide of Jay Moloney, Rose’s former (superstar) agent who had been sacked for cocaine addiction. Rose’s agency CAA, seeing parallels between Ivan Beckman and Moloney, withdrew its support and actively went on the offensive. “But the more that they tried to stop us, the more determined we were to make sure that the film reached the market,” says Rose. Ivans XTC did reach the market, getting a four-star review from Roger Ebert, yet sank with barely a trace.

It was with Rose’s second Tolstoy film, The Kreutzer Sonata (2008), that he really got into his stride. The film was based on the 1889 tale of the same name—Tolstoy’s case for sexual abstinence—which tells of a husband tormented by demons of jealousy and obsession as his wife takes a shine to the violinist she’s rehearsing with. Rose’s adaptation—again starring Danny Huston—hugged close to the Tolstoyan original, but was set again in Beverley Hills, filmed in friends’ houses and made on a tiny budget. Huston is its brooding centre—the same mixture of outward control and inner turmoil, but darker this time round, as he begins the long slide to a tragic ending. The film’s strong on the details of relationships—the innocence of early days, even when they involve collateral damage, the growing hostility, the way the bitterest arguments can turn into tender moments of confession and connection. Above all, it shows the terror you can have of your partner’s separateness from you, that the power they wield over you may be malignant and destructive. Set amidst scenes of graphic sex and glimpses of violent pornography, we see Huston’s deepening isolation: the unanswered phone calls, the pathetic attempts to break into the conversation when your lover’s hypnotised by someone else, the growing sense that something primal—a beast—has led you into the darkest of places. “We’ve been told a lie, all of us,” Huston thunders. “We’ve been told sex is good, sex is fun, sex is what you need. Is it? Look into my soul… and look at the devils that are tearing it apart. Now tell me it’s all so fucking wonderful.”

In The Kreutzer Sonata there’s a cameo by the British writer/actor Matthew Jacobs, playing a slightly smarmy chauffeur who, sensing Huston’s despondency, tries to cheer him up with some low-level misogyny. The chemistry between this odd couple—Jacobs a kind of Sancho Panza to Huston’s tortured Quixote—is noticeable, and it hands on a baton to Rose’s third film, Boxing Day (2012). Here the two actors are reunited, once more as chauffeur and passenger, in an adaptation of Tolstoy’s Master and Man (1895), a tale of a landowner and peasant who get caught in a blizzard en route to buying a piece of land. This being Rose, the action is moved to modern-day Colorado and the landowner has become a businessman, Basil, hungrily chasing the prey of some repossessed houses. The peasant Nikita is now driver Nick, and a Mercedes stands in for the horse and sleigh of the original.

We follow these two on a path to tragedy and a final, redeeming act as they bicker, joust with each other, and set out their differing visions of life. Basil’s is one in which greed is good, unethical acts keep the wheels of the economy spinning, and in which even Nick—if he earns his fee—gets extra crumbs from his master’s table. Nick, meanwhile, a recovering alcoholic with a failed marriage, a lonely Christmas, and a restraining order against him, sees the everyday tragedies in each newly empty house: evicted families forced to live in knockdown housing, children whose childhoods are ruined, parents caught in a poverty trap. That Nick advances these arguments with an unctuous passive aggression is what keeps the film interesting. We change sides several times and pity both of them trapped together in their sealed box, before the terrifying cold of the Colorado night dissolves all differences. This is the least operatic, and most touching, of the trilogy. It’s about where we all, somehow, inescapably, find ourselves: caught with resentment or guilt in the pecking order of life.

Perhaps the best thing these films can do—that any Tolstoy adaptation can do—is send us back to the original books themselves. But Rose’s films make a good substitute, and a better place to start than most. As the Covid lockdown of 2020 fizzles to its end and a host of new problems greet us, their spiritual and moral questions are worth pondering at length—before we emerge, blinking and impatient, into a facsimile of the world we left behind.