BLM

America Has Problems. Tearing Down Statues Won't Solve Them

To the extent we all care about the important underlying issues, such as fighting racial discrimination and promoting opportunity to all, we shouldn’t allow our culture wars over statues and symbols to dominate our discourse.

Earlier this week, a group of protesters involved in Black Lives Matter demonstrations spray-painted a statue of Winston Churchill in historic Parliament Square, adding the words “was a racist” under Churchill’s name. As critics of Churchill are quick to remind us, the former British prime minister supported the use of chemical weapons against rebellious Kurds and Afghans (though whether he advocated for the use of lethal gas is a subject of historical dispute).

Churchill also supported Britain’s colonial grip over the Indian subcontinent. When Mohandas Gandhi began his series of hunger strikes in protest of British rule, Churchill’s casually morbid reply sounded like something you’d hear from an action-movie villain: “We should be rid of a bad man and an enemy of the Empire if he died.”

Yet even Gandhi no longer gets a pass, apparently. In Washington, D.C., which also has witnessed protests, vandals defaced a Gandhi statue outside the Indian embassy. The motivations aren’t clear, but it’s believed they relate to Gandhi’s prejudiced views toward black Africans during his time as a South African lawyer (even if Nelson Mandela himself wrote an essay for Time magazine about how much he admired Gandhi’s tactics and values).

These are not isolated examples. In the aftermath of the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, the widespread spirit of protest has expanded to a wide array of cultural symbols—ranging from statues of Columbus to the movie Gone With The Wind. In Toronto, activists are demanding the renaming of a major street because it happens to be named after a long-dead Scottish politician who opposed the abolition of the slave trade. Some of these campaigns are questionable. But in the current environment, any claim or posture that’s seen as emanating from the Black Lives Matter movement, however indirectly, is taken as morally unassailable.

In fact, this trend already was well underway before Floyd’s death. But it has accelerated over the last two weeks. Last year, for instance, Nike pulled a planned shoe line featuring the Betsy Ross-designed colonial-era flag after a celebrity representative, Colin Kaepernick, complained that the symbol is associated with slavery and racism. The city of Charlottesville, Virginia voted to stop celebrating Thomas Jefferson’s birthday on concerns that such celebrations serve to whitewash a slaveholder. In San Francisco, a school will spend $600,000 removing a mural depicting George Washington’s brutality toward Native Americans and American slaves—an especially odd move given that the Depression-era artwork had originally been lauded for showing the cruel and aggressive elements of early American history.

Conservatives have long lampooned liberals as prosecuting a vendetta to erase history. But even putting aside such crude political caricatures, it isn’t clear how any of the above-listed campaigns would materially improve the lives of African Americans, Native Americans or other disadvantaged groups. Even Barack Obama—often described as the most liberal president in American history—was measured about his approach. When he (rightly) argued for changing South Carolina’s state flag—which until recently was emblazoned with a design honoring the Confederacy—he correctly argued that the flag “belongs in a museum.” Obama was not seeking to completely erase even the ugliest parts of American history, but rather to point out that they should be preserved as relics of the past instead of modern political symbols.

Unfortunately, both sides are quick to caricature their opponents whenever this debate flares up. I know, because I lived through a particularly raucous instalment when I was growing up in the southern state of Georgia, once the site of some of the Civil War’s bloodiest battles.

In the 1990s, then-Democratic Governor Zell Miller led a campaign to change his state’s flag, which at the time was a 1956 design that included the Confederate battle emblem. (The pre-1956 version, created in 1879, had been adapted from the first national flag of the Confederacy, the Stars and Bars.) “What we fly today is not an enduring symbol of our heritage, but the fighting flag of those who wanted to preserve a segregated South in the face of the civil rights movement,” he argued, noting that the flag had been adopted at a time when the South was gearing up to oppose federal integration efforts.

The flag was eventually changed in the 2000s (twice, in fact). But by then, the fight had exposed (and exacerbated) divisions between the two sides, both of which insisted the other side was extreme. Many of those who wanted the flag changed believed their opponents were hardened segregationists. In fact, most defenders of the 1956 flag simply saw it as a familiar part of their heritage and history.

Many Confederate monuments in the south were erected in the mid-20th century as a sort of protest against civil rights for African Americans. And some violent extremists, such as Dylann Roof, idolized the Confederate flag for explicitly racist reasons. But the same wasn’t true for the friends and neighbors I knew who owned Confederate flags. Most of them flew these flags not as any kind of political statement about race relations, but because they believed it was connected to their lineage. The Civil War was a war over slavery, and Georgia was on the wrong side of history. But ordinary Georgians suffered tremendously as General Sherman’s armies delivered history’s verdict in late 1864. Stories of battlefield defeats, scorched-earth tactics, and the humiliation accompanying Atlanta’s destruction created a narrative of victimization that was passed down from one generation to the next. Flag defenders’ claims that they were motivated by “heritage, not hatred” generally struck me as sincere.

Ultimately, I believe that Georgia officials were right to change the flag. As the years passed, more and more of the state’s population came from other parts of the United States, or from other countries. Fewer and fewer Georgians remained attached to Confederate symbols as markers of heritage or history. Newer arrivals, not to mention many blacks, viewed the old flag as honoring the Confederate States of America, a wicked institution that was established to defend the inhumane practice of human bondage. Our symbols should be inclusive and representative of who we are. Southern heritage doesn’t have to be focused on the trauma inflicted by a 19th-century war fought for a disgraced cause.

If I’d designed it, Stone Mountain—a massive rock-wall carving outside Atlanta overlooking a public park—would feature Jimmy Carter and Ray Charles, not Jefferson Davis and Stonewall Jackson. Carter and Charles represent the compassion, talent, and diversity encoded in Georgia’s heritage. A pair of 19th-century generals who sent legions of conscripted men to agonizing deaths to defend the institution of slavery don’t. But it’s possible to take this position without demonizing the other side, or demanding that those carvings be blasted away with dynamite.

A 2017 poll conducted in the state where I live today, Virginia, found that 57 percent of registered-voter respondents supported leaving Confederate monuments in place. I doubt this means that nearly 60 percent of my neighbors believe in the cause of the Confederacy. They simply place more value than I do in these historical markers of the state’s history, tragically flawed as it is.

A few miles north, at the National Mall in Washington, D.C., you can visit a memorial to the nearly 60,000 American service members who perished in the Vietnam War. The memorial lists the names of every one of them. What it doesn’t list are the names of the millions of Vietnamese and other Indochinese victims killed during the war. Many of those lives were smothered out by napalm, cut down by chopper fire, or massacred at My Lai. The war is simply described as “controversial” on the government website for the memorial.

It has always struck me as strange that our war memorials memorialize only the dead on our side. This one-sided presentation is something we simply take for granted. But think about it: Why should the life of a rice paddy farmer in Vietnam matter any less than a kid from Kansas sent to fight him? Ideally, we would build a wall many times longer on the Mall to pay our respects to the Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians who lost their lives as well. That doesn’t mean I begrudge the memorializing of American soldiers fighting (as I see it) an unjust war, only that I’d like to see the suffering of others recognized, too.

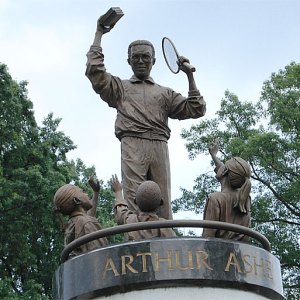

Arthur Ashe monument, Richmond Virginia

Whenever these controversies erupt, our first thought should be to add, not subtract. Visit Monument Avenue in Richmond, VA, for instance, and you will see statues memorializing Virginian Confederates from the Civil War, including Robert E. Lee, J.E.B. Stuart and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. But since 1996, there has also been another statue—this one honoring African-American tennis legend Arthur Ashe (1943–1993), who grew up and trained in the Richmond area. This doesn’t mean there isn’t a strong argument for taking down the older statues. But the inclusion of Ashe on Monument Avenue at least sends an important message: Our history isn’t frozen in the 1860s. Times change. And a boy who once would have grown up in Virginia as a slave instead would become the first black man to win Wimbledon and an inspiration to millions.

My own family wasn’t involved in the Civil War or the Vietnam War. But I did have family member who served in the Second World War. When Japan invaded colonial India, its soldiers captured a number of Indian troops, including my own grandfather, dispatching them to brutal prison camps in the Pacific. When I found out that US Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s former chief of staff, Saikat Chakrabarti, has a t-shirt emblazoned with the face of Subhas Chandra Bose, I was perturbed. Bose was an Indian nationalist who allied with the Axis powers during the war, even going so far as to meet with Hitler and organize an army of Indians who fought under the Imperial Japanese flag.

Subhas Chandra Bose, Center, in 1942.

Did Chakrabarti don a Bose t-shirt because he believed that the world would have been better off if the Axis won the Second World War? I’m very much guessing no—even if that would be the natural starting point of anyone who’d sought to get Chakrabarti “canceled.” The unfortunate fact is that Bose is today honored by some in India who view him more as an anti-British nationalist than an Axis quisling. (An airport in Kolkata is even named after him.) It’s likely that Chakrabarti finds this characterization persuasive. I can’t say I agree, but I also refuse to assume the worst about his viewpoint.

To the extent we all care about the important underlying issues, such as fighting racial discrimination and promoting opportunity to all, we shouldn’t allow our culture wars over statues and symbols to dominate our discourse. To quote Mike Chase, a criminal defense lawyer who has written for years about the litany of absurd and unjust federal laws on the books, “Stop tearing down statues. Start tearing down statutes.”

Zaid Jilani is a freelance journalist. Follow him on Twitter at @ZaidJilani.

Featured image: Demonstrators and spectators gather around a toppled Confederate statue known as Silent Sam Monday, Aug. 20, 2018 at UNC-Chapel Hill, N.C. (Julia Wall/Raleigh News & Observer/Tribune News Service via Getty Images)