Activism

America's Black Communities Are Suffering. Violent Protests Will Make the Suffering Worse

All in all, the evidence suggests that violent protests and rioting empower right-wing political forces, provide an opportunity for gangs to enrich themselves and exploit destabilized local populations, impoverish property owners, and harm long-term economic fortunes.

Protests sparked by the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin—an act that prosecutors describe as murder—have devolved into violence. Numerous small businesses have been destroyed, and at least one elderly shopper at a Target store was assaulted. A man has been shot dead.

This pattern of events is familiar because it has repeated itself numerous times over American history following acts of police brutality, especially in cases where, as with Floyd, the victim was black. First, large numbers of people protest peacefully, drawing attention to their cause and attracting national sympathy. Then, a smaller group turns violent, causing destruction in the community and sometimes harming innocent people. That smaller group sometimes includes people who exploit the chaos for their own ends. During the Baltimore riots of 2015, for instance, the looting of pharmacies led to opioids and other drugs flooding the market, likely feeding drug dependency, enriching gangs, and fueling more crime.

In the 1960s, thousands of Americans took part in non-violent protests in opposition to segregation. Their efforts helped lead to the passage of the Voting Rights Act and Civil Rights Act. But in the latter half of the decade, many protests became scenes of violence. In 1967 alone, there were 159 riots in major American cities.

Such riots often are cast as a form of righteous outrage, and progressives often are unwilling to denounce or even discourage them. Warren Gunnels, a senior staffer for Senator Bernie Sanders, seemed to downplay the events in Minneapolis, for instance, by describing growing wealth inequality in the US as the true form of “looting.” Such responses summon to mind the image of the rioters as underprivileged individuals punching up from their downtrodden place in society. But even to the extent one embraces that moral framework, their violence is counterproductive.

Looting = Over 600 billionaires increasing their wealth by $434 billion in 2 months of a pandemic that has caused over 38 million Americans to lose their jobs. https://t.co/uW7DRLfvbz

— Warren Gunnels (@GunnelsWarren) May 28, 2020

A recently published research article in the American Political Science Review examined the impact of different forms of protest in the 1960s on public opinion. Princeton University professor Omar Wasow, a veteran researcher in the sphere of race and politics, focused exclusively on black-led protests and how they were received by the public.

“The overarching question that led me to study 1960s protests was a puzzle I thought about a lot while growing up in New York, which might be summarized as how did we as a country shift from the victories of the civil rights era to the rise of ‘law and order’?” Wasow told me in an interview. “Both my parents had been activists in the Civil Rights Movement. For example, my father went to Mississippi to register voters as part of Freedom Summer. So, partly this was personal. Also, as I was growing up, I was trying to understand what had happened in the wake of those successes that left us with policies like the war on drugs and mass incarceration.”

His study found that nonviolent activism—like that practiced by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the American South—moved the public toward supporting civil rights, and even increased the vote share for Democratic presidential candidates in counties that were geographically proximate to protests.

This effect was particularly evident when nonviolent protests were met with violence, as was frequently the case with the SNCC. And it isn’t hard to imagine why: People feel sympathy toward innocent protestors being brutalized by racist mobs and authoritarian-seeming police officers.

The effect of violent protests, however, seemed to have the opposite effect. Indeed, Wasow believes that violent protests caused a shift among whites toward Republicans large enough to tip the 1968 presidential election to Richard Nixon, as scenes of violent protest shifted news coverage, elite discourse, and public opinion toward the theme of social control. “Members of Congress were deluged with ‘torrents of constituent mail’ in favor the 1968 Safe Streets bill,” Wasow writes, quoting the research of Yale professor Vesla Weaver. “Even liberal Democrats ‘felt compelled by public anxiety over crime and riots to vote for the bill.’ Polling data from August 1968 finds 81% of respondents agreed with the statement ‘Law and order has broken down in this country.’”

In the final analysis, Wasow believes, violent protests pushed white racial moderates from the Mid-west and Mid-Atlantic into a “law and order” coalition, and helped tip the presidency to the Republican Party.

SNCC members pray during a 1962 protest

Wasow concedes that the “transformative egalitarian” coalition created in the early 1960s had always been fragile, but that, in the absence of violent protests, it would likely have held together long enough to put Democrat Hubert Humphrey, lead author of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, into the presidency. In this alternative timeline, the Republican Party might not have become focused on the law-and-order campaigning and governing strategy that remains with us to this day, and which led, along the way, to the war on drugs and mass incarceration.

These consequences were actually foretold by some in the Civil Rights Movement, including the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. It is common on social media to see people quoting King’s statement that a riot is a “language of the unheard.” But in the same remarks from which this popular quote is drawn, King also stated that “riots are socially destructive and self-defeating.”

In February 1968, nine months before Richard Nixon’s election, King warned that increased rioting would lead to a “right-wing takeover.” He pointed to segregationist George Wallace’s presidential bid, saying, “Every time a riot develops, it helps George Wallace.”

“They’ll throw us into concentration camps,” he told supporters of the Poor People’s Campaign. “The Wallaces and [followers of the John Birch Society] will take over. The sick people and the fascists will be strengthened. They’ll cordon off the ghetto, and issue passes for us to get in and out. We cannot stand two more summers like last summer without leading inevitably to a rightwing takeover and a fascist state that will destroy the soul of the nation.”

After King’s assassination, his widow Coretta Scott King used her remarks at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church to implore his admirers to continue to act in accordance with his peaceful counsel. “Our concern now is that his work does not die. He gave his life for the poor of the world—the garbage workers of Memphis and the peasants of Vietnam. Nothing could hurt him more than that man could attempt no way to solve problems except through violence,” she said. “He gave his life in search of a more excellent way, a more effective way, a creative way rather than a destructive way. We intend to go on in search of that way, and I hope that you who loved and admired him would join us in fulfilling his dream.” In recent days, George Floyd’s girlfriend said something similar about how Floyd would have wanted his own mourners to act.

Corner of 7th & N Street NW in Washington, D.C., following 1968 riots

In the short term, violence can produce some highly visible benefits for victimized communities. It is very possible, for instance, that Chauvin would never have been criminally charged but not for the national attention focused on Minneapolis thanks to the violent protests. And the 2014 violence in Ferguson, Missouri led to police-training improvements and other policy reforms. But the long-term economic and social consequences of violence are almost invariably negative for the local community.

In 2005, researchers William Collins and Robert Margo examined the legacy of 1960s riots with a view to estimating the long-term consequences for neighborhoods where the riots occurred. They concluded that riots depressed the value of black-owned property between 1960 and 1970, with little rebound in the decade that followed. Riots were responsible for an estimated 10 percent loss in the total value of black-owned residential property in American urban areas, leading to an increased racial gap in property values.

I observed a case study firsthand during my visit to Baltimore in 2018, as part of a reporting project on a homicide wave the city was then suffering. Despite three years having passed since riots touched off by the killing of Freddie Gray in police custody, there was little evident progress made in areas impacted by the destruction. The city has continued to suffer from population loss. And many believe the riots indirectly fueled a surge in homicides in the years following, as police pulled back from proactively patrolling troubled communities.

A scene from the 2015 Baltimore riots

All in all, the evidence suggests that violent protests and rioting empower right-wing political forces, provide an opportunity for gangs to enrich themselves and exploit destabilized local populations, impoverish property owners, and harm long-term economic fortunes. And so it’s worth asking whether the well-intentioned progressives who are doing their best to cast the Minneapolis rioters in righteous terms are truly doing these underprivileged residents any favors. In 2018, a team of five researchers studied Baltimore’s violent protests and found that “moralizing” tweets—that is, tweets that cast the protests as a moral issue, helped predict acts of protest violence. In particular, “the hourly frequency of morally relevant tweets predicted the future counts of arrest during protests.” Which isn’t surprising: When we encourage and sanction violence, we get more of it. And if the violence isn’t benefitting the community, but is inflicting long-term harm, what is the point of encouraging it?

None of this is to say that we should respond to outrages such as Floyd’s killing with muted indifference. Nonviolent protest, media work, petitioning of government officials, and voter mobilization are all tools we can use to push back at injustice in a democratic society. Richmond, California, for example, is an example of a community in which civic activism and a get-out-the-vote campaign led to large-scale reforms of the police department that served to build community trust and reduce crime.

Many of the people doing the looting in Minneapolis are young. They’ve been cooped up for months without school or work, and they’ve been told they couldn’t even shake hands with their friends for fear of spreading disease. Many of us will remember what it’s like to be young, full of energy and anger, and caught up in occasional collective frenzies that felt, at the time, like they were accomplishing something. Not all violence can be avoided. But at the very least, those of us who are older and wiser can resist the urge to publicly signal that this is acceptable (or even praiseworthy) behavior.

A week from now, many of the privileged people signaling their approval for the rioters will have moved on to the next issue, even as many of the rioters, having been identified on video footage, are arrested. Worse, some may fall ill with cases of COVID-19 contracted during the fracas. Certainly, when November comes, Donald Trump and the Republican Party will be only too happy to have scenes of Minneapolis’ burning buildings and mayhem on heavy rotation. Violence played into the hands of the reactionary Right in 1968. And it may well do so again in 2020.

Zaid Jilani is a freelance journalist. Follow him on Twitter at @ZaidJilani.

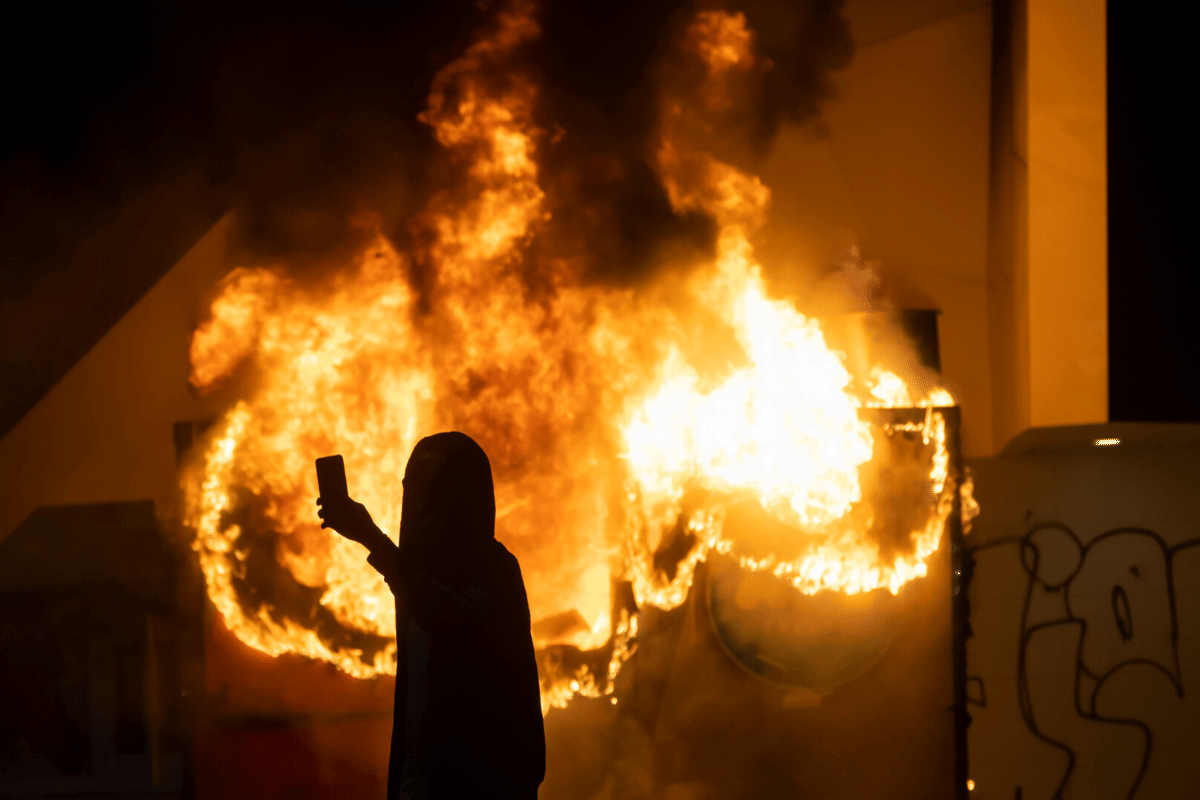

Feature image: A building in Centennial Olympic Park burns during rioting and protests in Atlanta on May 29th, 2020. (Photo by John Amis/AFP)