COVID-19

COVID-19 Superspreader Events in 28 Countries: Critical Patterns and Lessons

In the absence of any comprehensive database of COVID-19 superspreading events, I built my own.

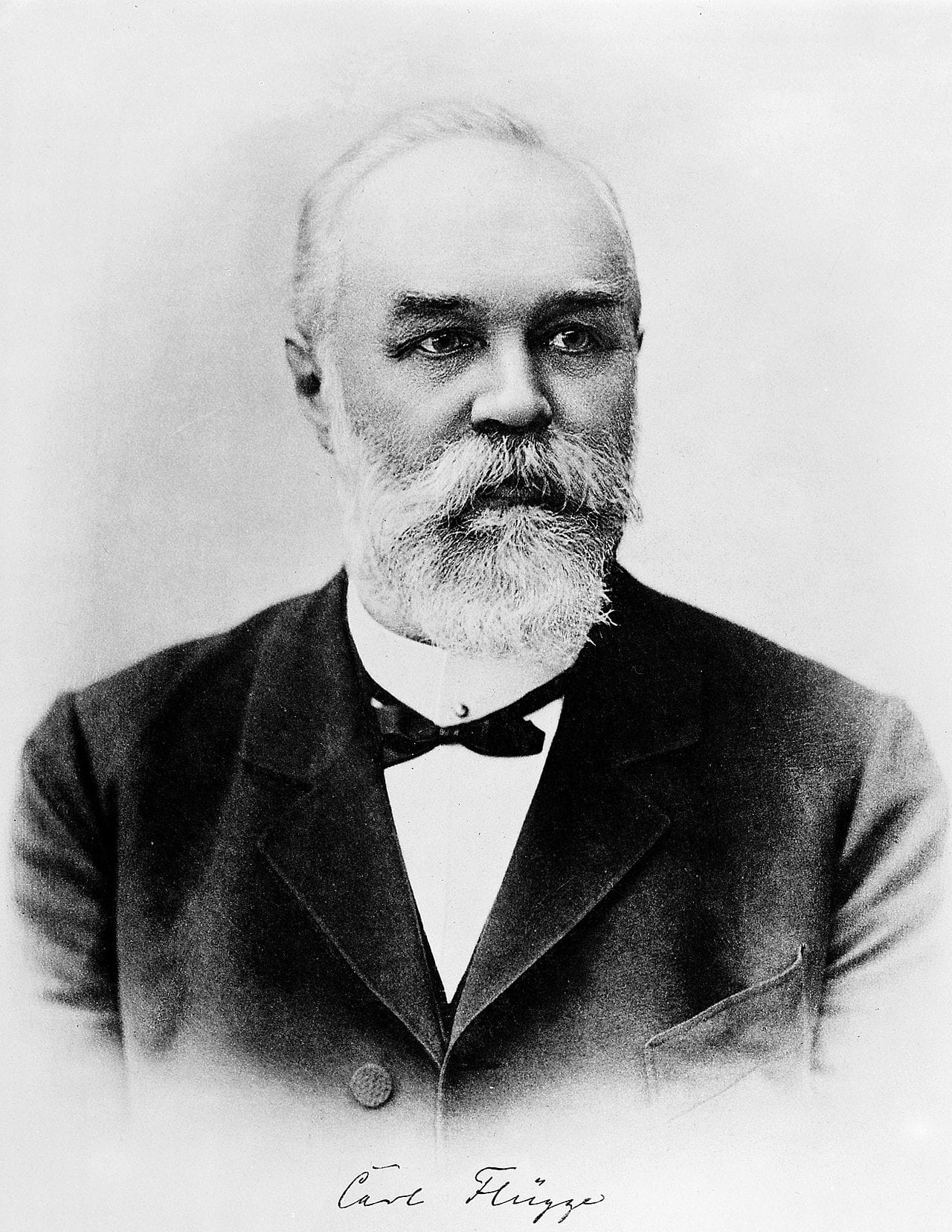

In 1899, a German bacteriologist named Carl Flügge proved that microbes can be transmitted ballistically through large droplets that emit at high velocity from the mouth and nose. His method for proving the existence of these “Flügge droplets” (as they came to be known) was to painstakingly count the microbe colonies growing on culture plates hit with the expelled secretions of infected lab subjects. It couldn’t have been pleasant work. But his discoveries saved countless lives. And more than 12 decades later, these large respiratory droplets have been identified as a transmission mode for COVID-19.

Flügge’s graduate students continued his work into the 20th century, experimenting with different subjects expelling mucosalivary droplets in different ways. Eventually they determined, as a 1964 report in the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine put it, that the quantity of expelled Flügge droplets varies markedly based on the manner of respiration: “Very few, if any… droplets are produced during quiet breathing, but [instead, they] are expelled during activities such as talking, coughing, blowing and sneezing.” A single heavy cough, it is now known, can expel as much as a quarter teaspoon of fluid in the form of Flügge droplets. And the higher the exit velocity of the cough, the larger the globules that can be expelled.

Yet if Flügge were with us today, he might be surprised by how little his science has been usefully advanced over the last few generations. As Lydia Bourouiba of the MIT Fluid Dynamics of Disease Transmission Laboratory recently noted in JAMA Insights, the basic framework used to represent human-to-human transmission of respiratory diseases such as COVID-19 remain rooted in the tuberculosis era. According to the binary model established in the 1930s, droplets typically are classified as either (1) large globules of the Flüggian variety—arcing through the air like a tennis ball until gravity brings them down to Earth; or (2) smaller particles, less than five to 10 micrometers in diameter (roughly a 10th the width of a human hair), which drift lazily through the air as fine aerosols.