Top Stories

Rethinking Human Ecology in the Age of COVID-19: Lessons from a Fish Market

Twelve of the viruses that Geoghegan and her co-authors detected are potentially novel strains.

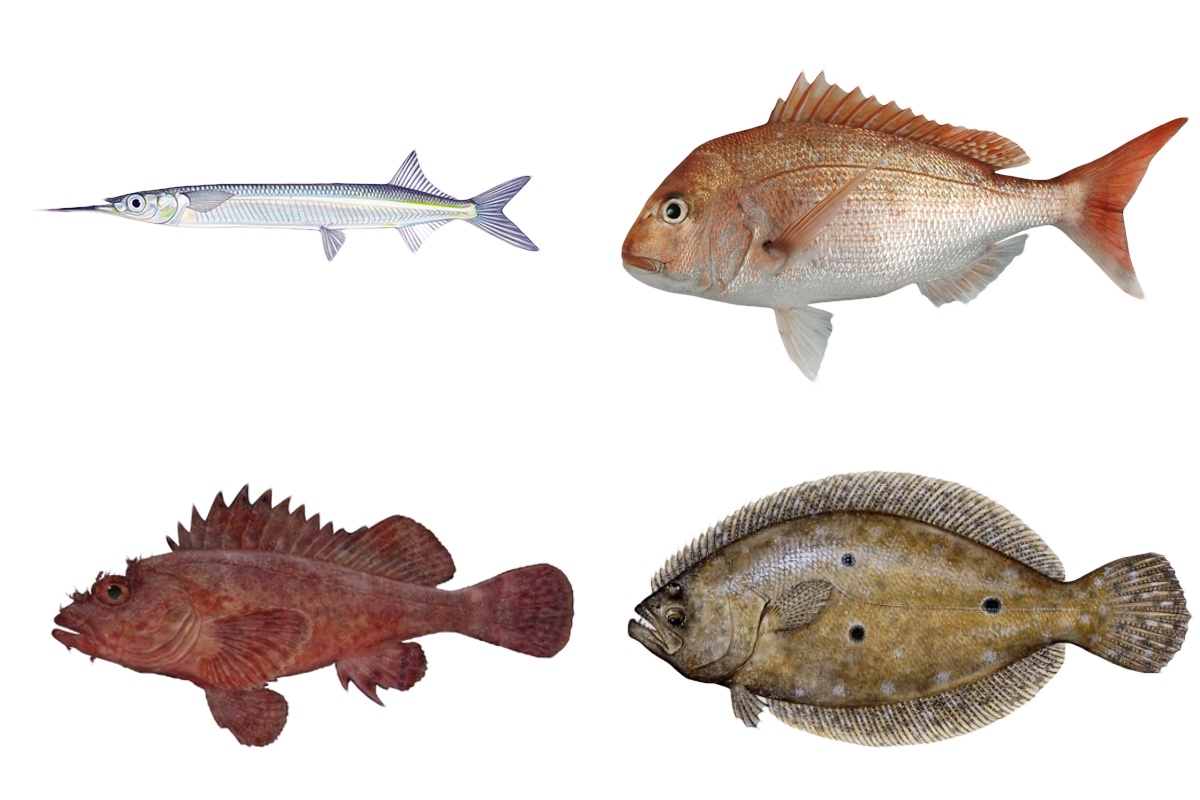

Three years ago, a young virologist named Jemma Geoghegan purchased 48 whole fish from a market in Sydney, Australia—12 each of Eastern Sea Garfish, Australasian Snapper, Eastern Red Scorpionfish and Large-tooth Flounder. The fish ended up in a freezer. And over the next few months, Geoghegan and her colleagues sent bits of their gills and livers to the Australian Genome Research Facility for DNA sequencing. Their goal was to better understand the assortment of viruses—collectively known as the “virome”—contained within seemingly healthy fish, a topic with obvious relevance to modern aquaculture.

The four species that Geoghegan sampled exhibit radically different appearances and behaviours. The Eastern Sea Garfish is thin and silvery. The Australasian Snapper is a hump-headed fish that looks like it’s wearing a helmet. The Eastern Red Scorpionfish is a spiky crevice-dwelling ambush predator with an enormous mouth, into which prey disappear whole. The Large-tooth Flounder is a wide, thin, asymmetrical fish that spends its life lying in sand or mud—always on its right side, so that it may behold the world above through the two eyes mounted on the left side of its body.

But all four species are alike in one respect: They harbour a wide array of viruses. And this isn’t unusual. As Geoghegan notes in her 2018 Virus Evolution paper on the subject, research suggests that fish may play host to more viruses than any other class of vertebrate. Unlike us, even healthy fish typically contain a “reservoir” virome that exists throughout the host’s life cycle.