One of the narrative paradigms in Kurt Vonnegut’s typology of stories is called “Man in a Hole”: Someone starts out doing pretty well at the beginning of a story, then plunges into a deep hole of misfortune, then scrambles out of it again. Jens Soering is that man in the hole. Soering’s promising life went off the rails at the age of 18, when the young German student at the University of Virginia began a love affair which culminated in the brutal double murder of Derek and Nancy Haysom, the parents of his girlfriend Elizabeth. That was act one. Act two involved an international flight from the law, hours of confessions, and a judicial decision which has shaped human rights law to this day. Act three begins with Soering’s conviction and sentencing to life in prison at a televised 1990 murder trial.

The pace of the drama then slows for act four: Working from his prison cell, Soering patiently constructs, over decades, an alternate history of the love affair and murders, and convinces a dedicated band of supporters that he is innocent of the murders to which he had earlier confessed. His patient efforts begin to pay off. Soering’s case became such a cause célèbre in Germany that it affected transatlantic relations: German Chancellor Angela Merkel raised Soering’s case during summits with Barack Obama, and former President of Germany, Christian Wulff, has visited Soering in prison and pleaded personally with American officials for his release. Dozens of members of the German and EU parliaments have petitioned the state of Virginia to pardon Jens Soering, or at least allow him to serve his sentence in Germany. A 2016 documentary brought Soering’s case to a worldwide audience.

Act five began with a twist on November 25th, 2019, with the unexpected announcement that the state of Virginia would release Jens Soering on parole from his life sentence—without granting the pardon he had requested—and deport him back to his country of nationality, Germany. Elizabeth Haysom was paroled to Canada the same day. Soering landed in Germany on December 17th amid a gaggle of reporters, supporters, and government officials. The expectation was that Soering would soon make the rounds of German talk shows, trumpeting his innocence claims and denouncing American justice. But act five is currently taking an ominous turn for Soering. Terry Wright, a decorated Scotland Yard detective who took Soering’s confessions in the mid-1980s, compiled a detailed 454-page long analysis of Soering’s case, refuting his innocence claims, and published the report on the Internet on January 22nd, 2020 under the pointed title: “A True Report on the Facts of the Investigation of the Murders of Derek and Nancy Haysom.” Owing to its sheer length, and the fact that it was written by a case insider who worked for two of the world’s most prominent investigative agencies (Wright later served as liaison officer between Scotland Yard and the FBI), the report has sown doubts even among many of those who accepted Soering’s claims at face value for decades.

Is Soering the victim of a miscarriage of justice, or a guilty murderer? The battle to establish history’s verdict on the case is joined, and both sides seem to be digging in for the long haul. Yet, as we will see, regardless of which side actually wins, there is one side which deserves to win: Jens Soering is guilty. His story is not one of innocence vindicated, but rather innocence fabricated.

Act One: Crazy Love

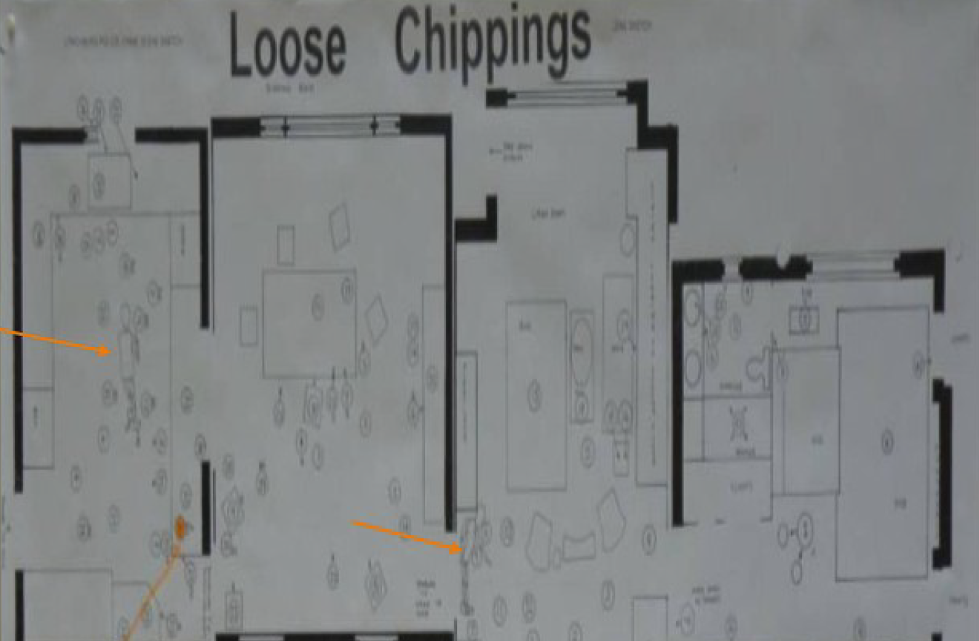

Jens Soering is the son of Klaus Soering, a mid-level German diplomat. Jens was born in Thailand in 1966, but grew up primarily in the United States, where he learned to speak fluent English. He was an exceptional student, and was admitted to the University of Virginia under scholarships which guaranteed him a free education. In autumn of 1984, Soering met another gifted student, the 20-year-old Elizabeth Haysom. Haysom, who had Canadian nationality, was the daughter of Derek and Nancy Haysom, a well-to-do couple with a cosmopolitan background: Derek Haysom had worked on mining projects across the globe, and Nancy was a descendant of Nancy Astor. The Haysoms lived in a small suburban estate near Lynchburg, Virginia called “Loose Chippings.”

The Haysoms had a difficult time raising Elizabeth. She had been sent to a demanding boarding school in England, where she learned to speak English in purest received pronunciation. But, as a 1990 book on the Soering case recounts, she rebelled, ran away from school, and bummed around Europe for months, experimenting with drugs and sexual self-discovery. Eventually coaxed to return, she enrolled in the University of Virginia. Yet she deeply resented her parents for their controlling, nagging, manipulative intrusions into her life. In the bizarre folie-à-deux relationship which grew up between Soering and Elizabeth Haysom, the parents grew into ogres. Elizabeth’s resentment congealed into active hatred, which Jens began to share.

It didn’t help matters that Derek and Nancy Haysom disliked Soering from the outset. Soering was smart and he knew it. This character trait, as we’ll see, would prove to be his hamartia. The Haysoms pressured Elizabeth to end her relationship with the odd, bookish, arrogant young German. She refused. Yet Elizabeth was still dependent on her parents financially, and spent her school holidays at home in Loose Chippings. If the Haysoms could be persuaded to endorse the relationship, and support Elizabeth financially, the couple could live on undisturbed. But what if this proved impossible? Within the hothouse of her relationship with Jens, an idea took hold: What if the Haysoms were out of the way? Soering wrote letters—later admitted into evidence at his trial—in which he confessed his “excessively bizarre sexual fantasies” and speculated about killing: “I have not yet explored the side of me that wishes to crush to any real extent—I have yet to kill, possibly the ultimate act of crushing…” When it came to Haysom’s parents, Soering noted ominously: “the fact that there have been many burglaries [near Loose Chippings] opens the possibility for another one with the same general circumstances, only this time the unfortunate owners…”

With the Haysoms dead, Elizabeth would inherit from their modest estate, and the love story of Jens and Liz could unfold without interference. The escalation of teenage resentment to cold-blooded homicide makes no sense, but very little about Soering and Haysom’s relationship did. In their letters, they sound like nihilists from a Russian novel, proudly invoking their brilliance and shared destiny as carte blanche to ignore conventional morality.

Act Two: The Killings

Vague plans for a final confrontation took shape, and were finally realized on March 30th, 1985. Jens and Elizabeth rented a car and drove from Charlottesville, Virginia (the location of the University of Virginia) to Washington, D.C., where they booked a room in the Marriott Hotel. Elizabeth began setting up an alibi: She bought movie tickets and room service for two, forged Soering’s signature on the credit-card receipt, and placed calls in which she pretended to be talking to Soering. Meanwhile, Soering drove the rental car from Washington, D.C. to Loose Chippings, a 600 km round trip.

The Haysoms, who had never met Soering at their home, were surprised by his visit, but let him in and set a place at the table for him. According to Soering’s confessions, the Haysoms were drinking when he arrived, and they served Soering several stiff drinks, on top of the beers Soering (who had almost no experience with alcohol) had drunk on the way for Dutch courage. The conversation escalated into a hysterical shouting match, and Soering suddenly attacked Derek Haysom with a knife, slicing his throat. However, Derek, as Soering put it later, “just wouldn’t lie down and die.”1The two men fought a vicious hand-to-hand duel to the death. Derek Haysom was stabbed 48 times, including 14 times in the back, and nearly decapitated. Soering prevailed, but wounded his left hand. Nancy Haysom ran to the kitchen, got a knife, and returned, hoping to defend her husband. Soering wrested the knife away from her and slit her throat. She staggered back to the kitchen and collapsed.

After the killings, Soering removed his bloody clothing and shoes and everything he thought he had touched, put them in a garbage bag, and threw it in a nearby dumpster. He also tried to clean up some of the blood, both his own and the Haysoms’, in the kitchen and bathroom. He “smeared around” the pools and stains on the floor and surfaces to try to obscure any shoe or fingerprints. As he left, he noticed that the front-porch light was still burning. Worried that this might attract notice, he re-entered the house, shoeless and wearing bloody socks, to turn off the light. However, he couldn’t find the switch, which was located in the master bedroom, not near the front door. The front porch light remained on, and duly attracted suspicion. When he was finally satisfied with his cleanup effort, he drove back to Washington, D.C. He arrived back at the hotel without pants, since he had had to throw away his blood-soaked clothes.

The Haysoms’ bodies were discovered three days later, on April 3rd, 1985, by a close family friend, Annie Massie. Authorities were puzzled: Nobody had any known motive to kill the Haysoms. There was no evidence of sexual assault, none of the valuables or liquor in the house had been taken, and there were no signs of forced entry—the Haysoms had evidently admitted the killer voluntarily. The Sheriff’s office in Bedford County, Virginia, desperate for leads, called up FBI headquarters in Quantico, Virginia (only a three-hour drive from Lynchburg), and asked for a profiler. The profiler, Ed Sulzbach, visited the crime scene and made some notes, speculating that the attacker might have been a female, and known to the victims. However, the process for requesting a formal FBI profile is complex and time-consuming—the local law-enforcement agency must complete structured reports to provide the FBI with a foundation on which they can build. The local sheriffs decided to rely on traditional detective work for the time being, and a full FBI profile was never created.

The Haysom family members were investigated, and authorities soon found out about the tension between Elizabeth and her late parents, and her bizarre escapades in Europe. Haysom also behaved strangely during interviews. A local man named Donald Harrington contacted police to tell them he had seen Soering with a bruise on his face and bandages on his fingers at a reception held after the Haysoms’ funeral. Further, neither Soering nor Haysom was able to provide a convincing explanation for the nearly 600 extra kilometers the police found on their rental car, except to say they got lost repeatedly. However, Haysom and Soering stuck to their Washington, D.C. alibi, which proved impossible to dislodge.

Investigators had little physical evidence to go on. No bloody fingerprints from outside parties were found at the crime scene. A luminol test on Haysom and Soering’s rental car showed no initial indications of blood. The Marriott Hotel manager Yale Feldman would later testify that, in 1985, surveillance camera footage was monitored in real-time by security not recorded. A partial bloody shoe-print at the crime scene wasn’t detailed enough to allow comparison. Police also found a slightly smeared sock-print, which would later loom large in the case. The critical fact, though, is that neither Soering nor Haysom knew that the police hadn’t found fingerprints, videotapes, or other conclusive physical evidence. Following standard procedure, the police had kept this information secret.

As other suspects were excluded, authorities focused more on Elizabeth and Jens. During an October 6th, 1985 interview, Soering continued to deny any knowledge of or involvement in the crime. Following this interview, the police requested that Soering provide blood, fingerprint, and footprint samples, as Elizabeth had done earlier. Instead, Soering emptied his bank accounts, wiped all the fingerprints from his own apartment and car, and fled the United States on October 13th, 1985, casting his full scholarship to the four winds. His flight propelled him to the top of the suspect list in the Haysom killings. Elizabeth Haysom soon joined him abroad. Together, they bummed around Asia and Europe for months, living on odd jobs and petty fraud.

Act Three: Arrests, Confessions, and Trials

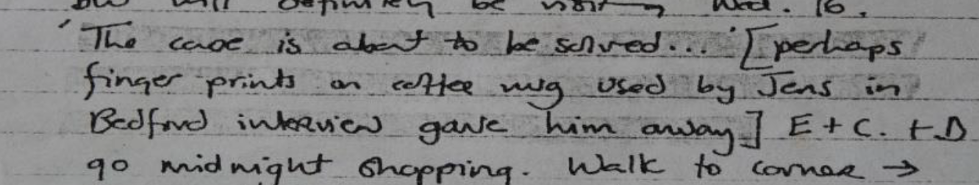

On April 30th, 1986, Haysom and Soering were caught by a store detective in London. They had been scamming stores by buying and returning expensive items, but had become sloppy. After their arrest, Soering, who had given the police the fake name of Christopher Platt Noe, consented to a police search of the apartment he and Haysom shared in London. This turned out to be the first of many catastrophic blunders Soering made in dealing with the authorities. Detectives found Soering’s authentic German passport and his correspondence with Elizabeth, which Soering had carried with him throughout his journeys. But that wasn’t all: Haysom and Soering had also started a joint travel diary to document the Bonnie-and-Clyde romance of their international flight from the law. Detectives Terry Wright and Kenneth Beever from the London Metropolitan Police (more famously known as Scotland Yard) were assigned to the case. Reading through the couple’s diaries, Wright found Soering’s bizarre fantasies, veiled references to some kind of violent crime, and suspicious references to fingerprints, including this entry in Elizabeth’s hand dated October 12th, 19852:

“The case is about to be solved… [perhaps finger prints on coffee mug used by Jens in Bedford interview gave him away].” Eventually Wright pieced everything together, and called the authorities in Bedford County, Virginia, the county in which the Haysoms’ murders had been committed.

Bedford County District Attorney Jim Updike and Sheriff Ricky Gardner flew to London to brief their colleagues, and on June 5th, 1985, Haysom and Soering, who were already in custody on the fraud charges, were formally questioned about the murders of the Haysoms. At first the police requested permission to hold the two “incommunicado”; that is, without contact to the outside world. Under UK law at the time, this could be done for brief periods to protect the integrity of an investigation, and there is a notice to this effect in the custody records. However, as Wright points out in his report, the case had already hit the papers, making the order superfluous, and it was rescinded almost immediately.3 Soering was allowed to speak to his lawyer and to the German embassy on June 5th, the first day of his questioning for murder. He waived his right to see his lawyer in writing, acknowledged being advised of his rights, and voluntarily answered the investigators’ questions. Over the next four days, from June 5th – 8th, Soering told Beever, Wright, and Gardner how he and Elizabeth had planned the alibi, how he drove alone to Loose Chippings, was invited into the house, drank cocktails with the Haysoms, killed them during a frenzied argument, and cleaned up the crime scene. Without any prompting, he provided dozens of details only the killer could have known. With only brief interruptions, these confessions were preserved on audiotape.

Why did Soering confess? The answer is obvious: He thought the police already had enough evidence to convict him. He assumed Elizabeth was already telling the police everything. He assumed the fingerprints he’d given during booking had already been matched to the crime-scene fingerprints. He assumed there was footage of him riding the elevator in the Marriott Hotel without pants in the early morning hours of March 31st, 1985. He knew the authorities had read the dozens of incriminating statements in the letters and the diary. In other words, he believed his goose was cooked. Further, as he admitted to the police, he was terrified of being sentenced to death.

So, he did everything he could to minimize his guilt. He denied there was a concrete plan in advance to kill the Haysoms. He refused to admit whether he had brought a knife to the encounter, which could be evidence of intent. He claimed to have acted in a fog of alcohol-fueled rage, and to not have fully grasped what he was doing. He also claimed, as we will see, that he had “only” slit the victims’ throats, and that someone else must have inflicted the additional stab wounds. Over and over, he stressed that he was confused, disoriented, and surprised by what happened at Loose Chippings that night. Soering was clearly adjusting his confession to preserve the possibility of what’s known as a “diminished capacity” or “diminished responsibility” defense: True, I committed the crimes and don’t have a full legal justification or defense, but I acted in a state of extreme emotion, without fully grasping the effect of my actions. This would have been a viable strategy under both German and British law at the time, which allowed sentence reductions for offenders who killed while in a state of intoxication and/or emotional distress.

Throughout the rest of 1986, Soering, with the support of his family and the German government, pursued a two-pronged strategy. First, they bolstered his diminished-responsibility defense. In late 1986, Soering gave two further detailed confessions to British psychiatrists, Dr. Henrietta Bullard and Dr. John Hamilton. The purpose was not to prove Soering’s innocence, of course, but to establish diminished capacity. Dr. Bullard concluded, in a court’s later summary, that Soering “was immature and inexperienced and had lost his personal identity in a symbiotic relationship with his girlfriend—a powerful, persuasive, and disturbed young woman.” Both Bullard and Hamilton (whose report is available here) concluded that Soering should, if tried under the UK Homicide Act of 1957, be convicted only of manslaughter, not murder.

The second prong of the strategy was to try to have Soering tried anywhere but Virginia. To this end, Soering arranged to give a full confession to a German prosecutor on December 30th, 1986. Soering was accompanied by his own German defense lawyer during this interview, which was recorded, transcribed, and translated into English. The full 43-page confession, which was introduced at Soering’s trial, can be read in its entirety here. Soering also petitioned the courts against being extradited to Virginia, where he could face capital punishment. The case eventually reached the European Court of Human Rights which, in a landmark 1989 decision, sided with Soering. Regardless of whether or not executions were always unlawful, the Court held, the long wait for executions was itself a form of “torture or inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment” prohibited by Article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights. Soering could not, therefore, be extradited to Virginia as long as Virginia planned to seek his execution. Soering v. the United Kingdom has since become one of the most famous and influential cases in international human-rights law—it was cited, for instance, by the Constitutional Court of South Africa in its landmark 1995 ruling abolishing capital punishment.

After the Soering decision in 1989, Virginia agreed not to seek capital punishment in Soering’s case, paving the way for his extradition to Virginia. Soering hired two experienced lawyers to represent him, Richard Neaton and William Cleaveland. They had shocking news: The state of Virginia, unlike the UK and Germany, does not recognize the “diminished capacity” defense. The idea of giving a sentencing discount to a murderer or rapist based on their emotional state or intoxication has always been considered a liberal innovation in criminal law, and Virginia has never been known for embracing liberal innovations. So, when it was invited to create a defense of diminished responsibility in 1985, the Virginia Supreme Court bluntly refused, holding that “evidence of a criminal defendant’s mental state at the time of the offense is, in the absence of an insanity defense, irrelevant to the issue of guilt.” Soering could never satisfy the high burden of showing legal insanity. Soering’s intended defense was, therefore, stillborn.

What could he do now? Soering’s flight was extremely suspicious, and there was little hope of keeping his many detailed confessions out of evidence. Elizabeth, who had agreed to extradition, pleaded guilty, expressed remorse, and received two 45-year prison sentences in 1987, would likely also testify at Soering’s trial. No third party had motive, means, or opportunity to murder the Haysoms except Haysom and Soering, making them the only two plausible killers. This left Soering with only one realistic way out: to claim that Elizabeth, not he, had killed the Haysoms. But why would he confess to her crime? In the new version he made public at his 1990 murder trial, Soering unveiled his motivation for taking the fall: He wanted to save Elizabeth, the love of his life, from the electric chair. This was the story he told the jury at his 1990 trial in Bedford County, Virginia, which was recorded on video in its entirety and broadcast live on many TV stations. Yet Soering’s new story was filled with contradictions, and he was broken on the wheel of cross-examination by district attorney Updike. The jury deliberated for only a few hours before convicting Soering, and he was sentenced to life in prison.

Act Four: Forging an Alternate Reality

Jens Soering was now serving a life sentence. Parole was a possibility, but that lay years in the future. In the meantime, Soering had nothing but time, and now had access to most of the records of his case. He must have simmered with anguish when he finally realized that most of the physical evidence he had feared had never even existed. It must have also been a blow to read the records of Elizabeth’s interrogation in London. From June 5th – 8th, while Soering was confessing in detail, Elizabeth had said nothing incriminating. She broke down only late on the evening of June 8th. If both of them had remained silent, it would have been much harder, if not impossible, to convict them.

Now Soering, burning not with remorse but with regret, made another mistake: in 1995, he self-published an ebook about his case entitled Mortal Thoughts, which can be read here. Any criminal defense lawyer reading this last sentence will freeze in horror. Even innocent defendants can get themselves into serious trouble talking about their cases. Guilty ones invariably stumble into dozens of traps. Soering was a good deal smarter than most prisoners, and avoided some of these traps. But, as we will see, he did not avoid them all.

Mortal Thoughts begins with Soering’s autobiography and an account of his relationship with Elizabeth. In the fourth chapter, he comes to the murders. According to Soering, the trip to Washington, D.C. was an innocent “mini-vacation” with no ulterior purpose. During this vacation, however, Elizabeth suddenly confessed to Soering that she had resumed using heroin, in violation of a promise she’d made to her parents. Addiction, Soering announces, is a disease. I will help you overcome it.

Elizabeth is grateful, but adds some ominous news: she owes money to her drug dealer, “Jack Bauer.” Jens tells her that he’ll pay the debt. Alas, she responds, that won’t work. Bauer wants me to repay the debt by transporting a big load of “drugs” (we’re never told exactly which kind) back from Washington, D.C. to Charlottesville. Bauer wants to meet her right now, in the late afternoon of March 30th, 1985. She must go alone, otherwise Bauer would get suspicious. Elizabeth leaves alone in the rental car to pick up the drugs. Soering waits for hours, becoming increasingly anxious. Soering forges an alibi for Elizabeth by buying two movie tickets and ordering room service for two. Soering claims this alibi was necessary to convince Elizabeth’s parents she wasn’t using drugs, although he is unable to explain why they would demand formal documentary evidence, or why movie tickets would prove anything.

Around 2am, Elizabeth returns to the room in the Marriott Hotel. She’s wearing different clothes than when she left:

Elizabeth speaks in a monotone while staring at the floor in front of her. Over and over she repeats variations of the same phrases: I’ve killed my parents, I’ve killed my parents. But it wasn’t me, it was the drugs that made me do it, the drugs did it, not me. They deserved it anyway, my whole bloody childhood, always sending me away, and now they want to control every little thing, it serves them right, they deserved it. If you don’t help me, they’ll kill me, you have to help me or I’ll go to the electric chair, you have to help me or they’ll kill me.4

Soering sees “reddish-brown smears” on her forearms, which are clearly “blood.”5 Later in the book, Soering proclaims his regret for not preventing the killings: “I arranged an alibi and became an accomplice in murder without even knowing it. I should have stopped her! But because of my foolishness, Derek and Nancy Haysom died at the hand of their own daughter.”6

So this, as of early 1995, is Soering’s story: Instead of picking up the drugs for “Jack Bauer,” Elizabeth decided to spontaneously murder her parents, nearly beheading her own father (who was 10 cm taller and 25 kg heavier than she was). She did all of this—as well as driving 600 km alone, mostly at night—during a rush produced by some unspecified “drugs.” Jack Bauer, having been left in the lurch, obligingly disappears from the story. After hearing Elizabeth’s confession, Soering has what he sarcastically calls his “brilliant idea”: he will confess to the murders instead of Elizabeth! As the son of a diplomat, he would enjoy immunity. Germany would never let the U.S. prosecute him for the death penalty, and he would be transferred to Germany. There, as a young offender, he would receive a sentence of perhaps 10 years. Then he and Elizabeth could resume their love affair. Elizabeth agrees to accept his “sacrifice.” But to switch roles convincingly, Soering has to know what happened. They trade stories:

I told Liz what I had done, so she could confess convincingly how she arranged the alibi. Then Elizabeth described the scene of crime, and I tried to imagine how I might have been driven to kill her parents. She did not tell me why she had driven to Lynchburg or what had actually happened at Loose Chippings, and I did not want to know. We never mentioned the murders directly to one another again.7

After Soering and Haysom were arrested in London, his “sacrifice” is realized—he falsely confesses to the murders to protect Elizabeth, while she confesses only to creating the alibi in Washington, D.C. But wait, the skeptical reader asks, why would Elizabeth have to confess to anything? She could simply claim Soering killed her parents without her knowing anything about it—exactly the mirror image of Soering’s story. Instead, the pair decide she will confess to being an accomplice to murder, which could put her in prison for life. This is just one of dozens of questions raised by Soering’s bizarre new tale.

Overall, though, Soering’s new story is an impressive piece of retconning, considering the reams of incriminating evidence it has to explain away. If you squint at it from the right angle, and shut off your critical faculties—in other words, if you want to believe it—you can convince yourself it makes just enough sense. News articles from 1995 show the book serving its initial purpose of attracting attention to Soering’s case. Soering eagerly sought press coverage, filed appeal after fruitless appeal, and asked constantly for help from the outside world. Gradually he acquired a passionate band of followers—people who wanted to believe.

Soering’s diverse band of supporters—who I will collectively refer to as Team Soering merely for convenience—has grown to include celebrities such as Martin Sheen, John Grisham, and music producer Jason Flom, who has devoted much energy to the worthy cause of highlighting cases of wrongful conviction. Amanda Knox, an American woman who was convicted of and later acquitted of murder by Italian courts in a massively publicized case, devoted a series of podcasts to Soering’s case. Many German journalists have also joined Team Soering.

This is no surprise, since Soering tailored his story to resonate with prejudices of educated Europeans concerning the American justice system, including disdain for the death penalty, the jury system, the “third-degree” interrogation techniques used by American police, and the tradition of electing judges and prosecutors. It also didn’t hurt that Soering was intelligent, articulate, and fluent in German and English. He leavened his story with self-deprecating humor and literary allusions. Further, as a medium-sized, thin, bespectacled white man without tattoos or attitude, he simply didn’t look like most peoples’ idea of a double murderer. German reporting on the case became increasingly one-sided; Soering was allowed to give long interviews blackening the character of Elizabeth Haysom (who was depicted as a femme fatale who manipulated him into taking the blame for her crime) and the British and American investigators who proved his guilt, without facing any critical questions.

In the mid-2010s, Soering landed a coup in the form of support from Sheriff J.E. “Chip” Harding of Albemarle County, Virginia. It’s not every day that a sitting sheriff takes up the cause of a convicted double murderer. In 2017, Harding wrote two letters to the Governor of Virginia decrying what he took to be flaws in the case against Soering. Chuck Reid, a former investigator for the Bedford County Sheriff’s Office who worked on Soering’s case, also began arguing on Soering’s behalf. At his parole hearings, German diplomats put Soering’s case, pointing to the supposed flaws in his trial, and suggesting that Soering be paroled to Germany. Yet until 2019, all parole and pardon requests were denied. Soering became increasingly bitter, as reflected by the headline of a 2011 newspaper interview (quoting Soering) “‘Rage, it’s simply rage.’”

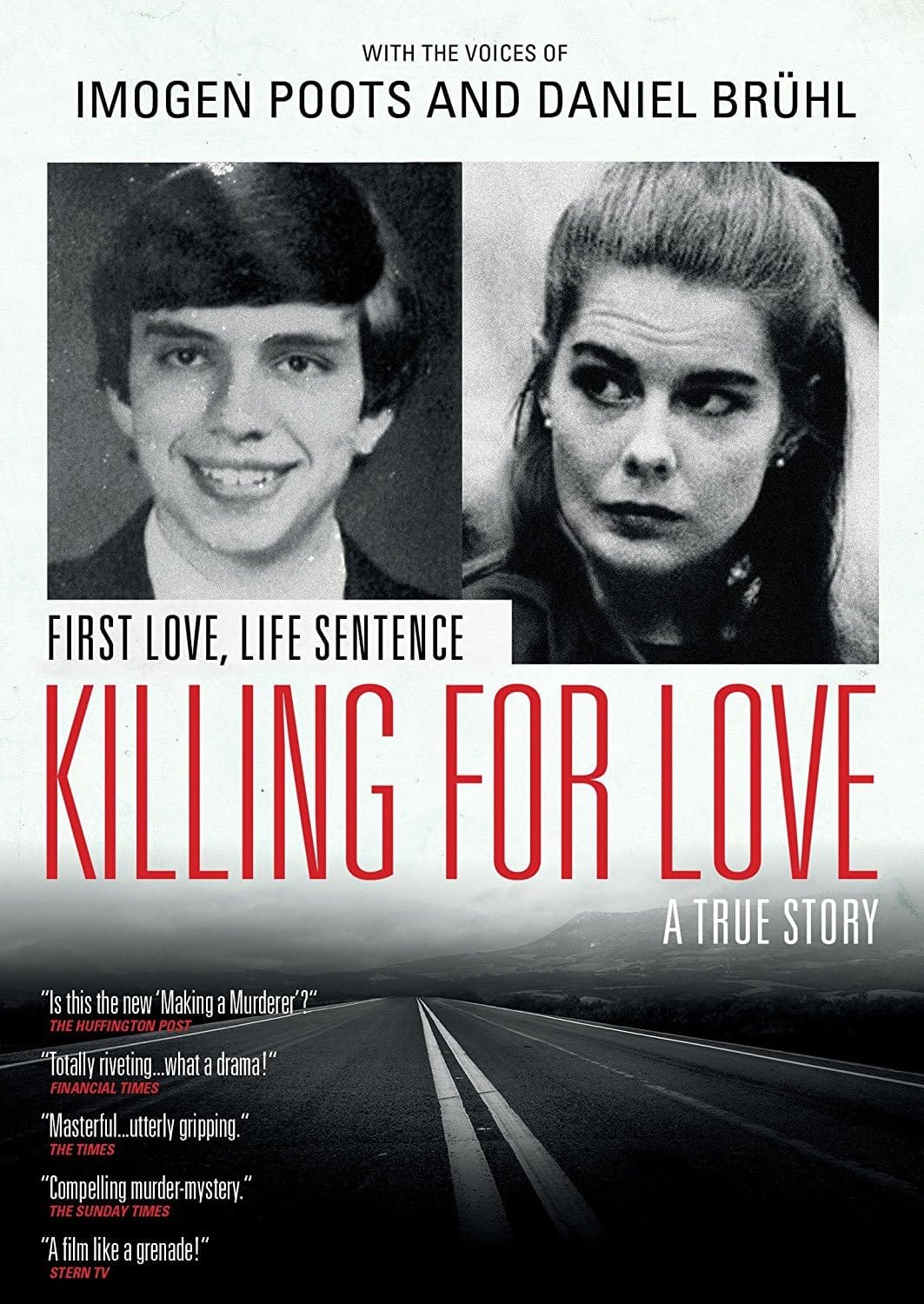

In 2016, German journalists Karin Steinberger and Markus Vetter released the documentary Killing for Love. The film is constructed around a long prison interview with Soering, interspersed with interviews with Soering’s supporters, clips from his trial and confessions, and reconstructions of events from Soering’s perspective. The first seconds of the film—accompanied by the none-too-subtle strains of “I Put a Spell on You”—announce that the directors are parti pris. The filmmakers simply brush aside the most damning evidence against Soering and broadcast his claims without any critical scrutiny, using manipulated excerpts of Soering’s confessions and the testimony at Soering’s and Haysom’s trials. Despite—or because of—this grotesquely heavy-handed presentation, the film received many positive reviews, as documented on its website. To people with no independent knowledge of the case, the film is no doubt convincing.

Yet at the same time other actors close to the case were preparing a thorough defense of Soering’s conviction. By the 2010s, Terry Wright and Kenneth Beever were senior Scotland Yard officials with decades of experience. Wright had spent years working at FBI Headquarters in Quantico, Virginia, as the official liaison between Scotland Yard and the FBI. Neither Wright nor Beever had thought much about Soering’s case since testifying at his trial in 1990. Then, in 2016, they read news accounts in which Soering claimed that “new DNA evidence” had “excluded” him from the crime scene. They also discovered that Jens Soering was still claiming he had been intimidated and threatened into confessing by Wright and Beever. Wright began looking into Soering’s claims. Disgusted by what he found, he decided to supply the missing context in a letter to Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, who was considering Soering’s pardon petition. Wright soon realized the enormous scale of the job he had chosen for himself:

During my research into what Soering has said since 1990, I read a draft copy of his book Mortal Thoughts circulated on the internet. Soering claims that this book is a true account of the murders but, almost every paragraph is either made up, or it’s a lie. There are so many lies, about so many things, that it cannot be a simple case of a differing opinion, or a different interpretation of the facts, Soering is clearly saying things that I know to be untrue.

Wright realized that people were likely to be taken in—that they had been taken in—by Soering’s carefully-sculpted alternate reality. What started out as a private letter from Wright to Governor Northam eventually grew into a 454-page report debunking every single claim Team Soering has ever advanced. I was given exclusive access to this report before its wider publication, and published several articles in a German newspaper summarizing its conclusions. While Wright was compiling his report, an anonymous blogger began the website Jens Soering — Guilty as Charged, which likewise documents every misstatement, distortion, and biased claim put forward by Soering and his supporters, and provides links to many full-length original case documents, including the “True Report” itself.

An awkward fact leaps out at anyone who reads the statements of Soering’s supporters: They almost never endorse his innocence. For his part, Soering still insists he didn’t commit the crime: His Twitter bio proclaims him “innocent” (unschuldig). Yet his supporters never mention Mortal Thoughts, even though it’s the only comprehensive English-language statement of Soering’s case for innocence. In fact, someone has gone to great lengths to scrub Mortal Thoughts from the Internet completely; it survives only on the Internet Archive website. Karin Steinberger, Soering’s chief German media supporter and co-director of Killing for Love, always inserts a disclaimer when she talks about the case saying she “doesn’t know” whether Soering is guilty or not—even as she claims the problems in his case call the entire American criminal justice system into question. Chip Harding, the sheriff in Soering’s corner, has also never come straight out and declared his belief in Soering’s innocence, confining himself merely to arguing that Soering wouldn’t be convicted if tried again today.

The fact that Soering’s supporters conspicuously fail to endorse his version of the story hasn’t stopped them from arguing his case, though. Until recently, the best introduction to his version was a 93-page long pdf entitled “The Soering Case Made Simple” which was hosted on Soering’s website. Like Mortal Thoughts, it has recently been scrubbed from the Internet without notice or explanation, but an archived copy is available here. Drawing on this document and Mortal Thoughts and, on the other hand, on Wright’s 454-page report, we can now assess how much of Soering’s alternate reality can withstand scrutiny.

Of course, Soering’s confessions are the elephant in the room. Soering now claims he confessed only because he was denied contact with his lawyer and pressured by English and American investigators during his interrogations over the course of June 5th – 8th, 1986. Despite this pressure, he claims he had resolved to tell the detectives “as little as possible”8 from June 5th – 7th, but finally broke down and confessed on June 8th, realizing that he was running out of time to “save” Elizabeth from the death penalty.

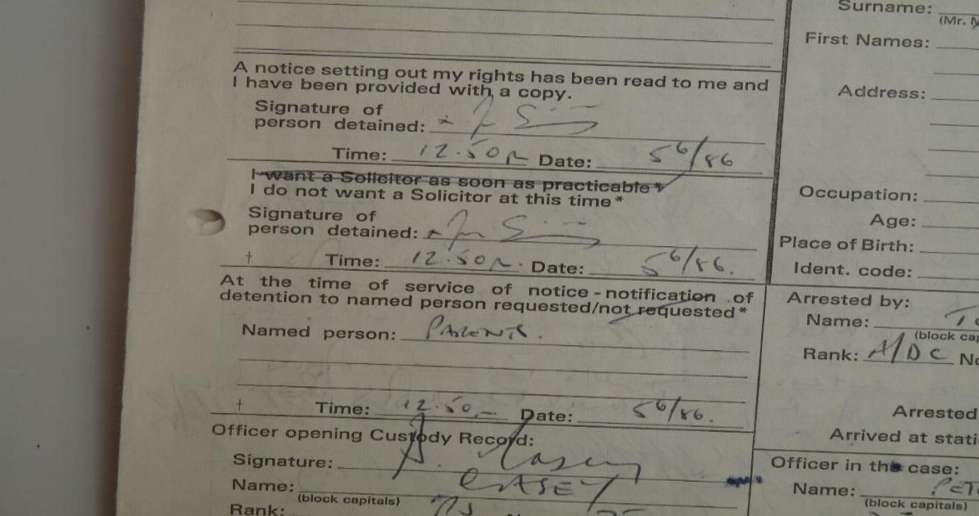

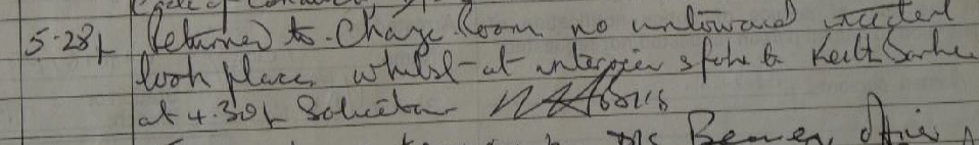

Every one of these claims is false. As a former Scotland Yard employee, Terry Wright has access to records of Soering’s stay in the UK. There, he found Soering’s signed written waiver from 12.50pm on June 5th, 1986 confirming he’d been advised of his rights and expressly declining a meeting with his solicitor9:

Soering seems to have realized that people might find out about his written waiver, so he has a backup excuse. He claims that “some time between 7:00 p.m. and 7:40 p.m.” on June 5th, 1986, “[t]he English Detective Sergeant Kenneth Beever had come to my holding cell alone and told me that Liz might fall down and hurt herself if I did not drop my demands for a lawyer.”10

There are many problems with this story. First, as we see, Soering waived a meeting with his lawyer hours before Beever’s alleged threat. Second, Beever did not threaten Soering. Both gave sworn testimony in March 1990 hearings on the admissibility of Soering’s confessions. Judge William Sweeney ruled: “Simply stated, I do not believe Soering on this issue. He produced no corroboration, written or oral. The officer emphatically denied making such statement, and the subsequent taped interviews which the court listened to for five hours gave no suggestion that Soering was acting under duress at any time.” Interestingly, when Soering published an expanded German translation of Mortal Thoughts (entitled Nicht Schuldig!, or Not Guilty!), either he or his publishers removed any mention of his false accusation against Beever, doubtless fearing a defamation lawsuit.

Incidentally, those five hours of detailed confessions were given June 5th – 7th, 1986 when Soering claimed to be telling detectives “as little as possible.” The final lie is that Soering was denied access to a lawyer. Soering was permitted to speak to his lawyer at 4.30pm on June 5th, 1986, as confirmed by a notice—made in Soering’s presence—in his custody record: “Returned to Charge Room no untoward incidents took place. Whilst at interview spoke to Keith Barker at 4.30pm solicitor.”11

Nothing about Soering’s account of isolation and threats is true. Thus, Team Soering now moves on to Plan B: Even if Soering’s confessions were freely given after legal advice, as they were, they conflicted with the crime-scene evidence. This argument is based on Soering’s claim that he knew the crime scene only from Elizabeth’s brief second-hand account (we recall that Soering said Elizabeth only described the crime scene and never revealed “what had actually happened at Loose Chippings”). Team Soering now argues that Soering’s confessions place him at the wrong position at the dinner table, mistakenly identify what Nancy Haysom was wearing and where the bodies were found, don’t describe the murder weapon accurately, and require Soering to have killed two people in different places simultaneously—to name just a few of the seemingly numberless hair-splitting quibbles Team Soering has put forward to try to attack the confessions.

Sometimes they have strayed into outright falsehood: Wright observes that Soering’s lawyer Steven Rosenfield, in this interview with local journalist Coy Barefoot, claims that Derek Haysom was “about six-three, 260 pounds.” According to his autopsy report, Derek Haysom was 5’8” tall and weighed 165 pounds—in other words, the same size as Soering.12 Rule 4.1 of the Virginia Bar Association’s Rules of Professional Conduct states: “In the course of representing a client a lawyer shall not knowingly… make a false statement of fact or law.” We should charitably assume Rosenfield did not knowingly lie, but this blunder does him little credit.

In any event, over dozens of meticulous pages replete with diagrams, illustrations, and long excerpts from the confessions, Wright gives the lie to all of Team Soering’s claims but one. First, Soering’s 1986 confessions contained dozens of accurate details which had never been released to the public:

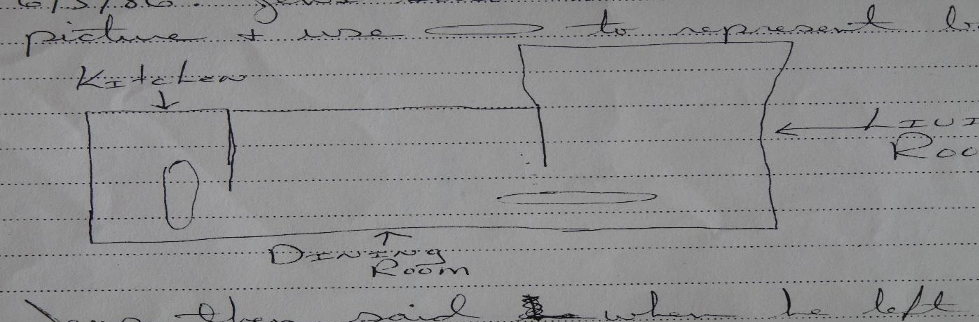

Soering told us that the Haysoms were drinking when he arrived at their home. The autopsies revealed high levels of alcohol in the victims. He described the dining table settings exactly as they were found by police, even telling us who sat where. He told us that he removed his shoes and sock impressions were found in the crime scene. Soering also told us that he cut the throats of his victims and their throats were cut as he said. He said that Derek Haysom was hitting him about his head and that he cut his fingers on his left hand during the struggle and showed us the scars. A witness reported seeing him with bruises on his face and bandages on his left hand. Soering said that he tried to clean himself up in the kitchen and bathroom. These are the locations where type O blood was found and Soering has type O blood. He also drew sketches of where the dead bodies lay, describing a pool of blood around Nancy Haysom’s head, and how Derek Haysom was laying on his side with his legs towards the doorway, exactly how they were found. Do not believe the lie that Soering tells, saying he indicated the wrong locations for the bodies. The distribution of the various blood types in the crime scene are also consistent with what Soering said in his confessions.13

Wright disproves the “lie” that Soering gave the wrong locations for the bodies by comparing a sketch of the crime scene in Soering’s own hand with the official courtroom crime-scene diagram (the orange arrows pointing to the bodies were inserted by Wright) 14:

The bodies were where Soering said they would be, except that Derek Haysom’s is rotated slightly less than 90°. Soering repeatedly warned detectives he could only vaguely remember where the bodies were located, and that turns out to be correct. There is one minor error in Soering’s confessions: After struggling to remember what Nancy Haysom was wearing, Soering guessed “jeans,” then hastily added that this part of his memory was “very confused.”15 Haysom was in fact wearing a flower-patterned housecoat.

Yet Wright’s report highlights other, even more damning portions of Soering’s confessions: Information which could only have come from the real killer, not from Elizabeth’s brief description of the “crime scene.” One such piece of information was Soering’s account of returning to the house to try to find the switch for the porch light—which Elizabeth would obviously have known wasn’t located next to the front door. This piece of information explained why luminol tests showed bloody footprints leaving the house, then returning to it. While discussing the trip back from Loose Chippings to Washington, D.C., Soering noted that he had arrived back at the hotel without pants, and noticed the surveillance cameras in the elevator: “Soering: ‘Um … yes, there could be a video tape of the elevator, which does show me without my trousers on because that’s in fact what happened.’”16The police didn’t have these video tapes, but Soering of course didn’t know this. This admission is obviously impossible to square with his post-1990 story, in which Elizabeth returns from killing her parents fully clothed. The conclusion is inevitable: Soering told police he rode the elevator without pants because, to quote him, “that’s in fact what happened.” He assumed that the police already knew this, so there was no point in lying about it.

Another intriguing aspect of Soering’s confessions is the “mutilations.” Derek Haysom was stabbed many more times than necessary to kill him. Soering adamantly denied any memory of these “atrocities” (in his words) performed on the victims’ bodies in addition to the killing. Soering was obsessed by the idea that these additional injuries not only aggravated the culpability of the killings, but may even have also constituted a separate offense. As Wright—who questioned Soering personally—notes: “Almost all of the interview of June 7, 1986, was about splitting the ‘atrocities’ from the murders.”17

Soering cherry-picks a brief excerpt from this interview to try to bolster his argument that he confessed falsely:

On June 7, while I was still trying to persuade the policemen to allow me to see my attorney, I nearly panicked and told the truth.

An English Detective Sergeant named Kenneth Beever asked me, “Would you consider, under those circumstances, taking into account your answer, pleading guilty to something you didn’t do?”

“Would I consider doing that?”

“Yes.”

“I can’t say for sure right now, but I can see, I can see it happening, yes. I think it is a possibility. I think it happens in real life.”

In Mortal Thoughts, Soering claims that this was a sort of real-time warning that he was confessing falsely.18 But Terry Wright has a much darker explanation. At various points during his interviews, Soering requested the tape recorder be turned off so he could discuss a certain sensitive aspect of the case. But Wright was there when the tape recorder was shut off, and remembers what Soering said: He felt someone had watched him leave the house after he killed the Haysoms, and then entered the house and desecrated the victims’ bodies.19 What’s more, Soering had a suspicion who this was: Annie Massie, the close friend and bridge partner of the Haysoms (she hosted a reception following their funerals), who had a key to their house. Soering speculated that Massie may have been some kind of voodoo priestess. While the tape was rolling, Soering, without mentioning Massie’s name, stated that he believed someone had assembled a group for a “ritual” desecration of the bodies: “And the murder was committed, I think there’s a huge difference between that … and then afterwards, I don’t know, phone calls being made and the group assembled for some sort of ritual, alright.”20The short passage which Soering suggests was a warning that he might confess falsely was no such thing: Just before that exchange, Soering had been discussing the atrocities. His statement related not to the murders themselves, which he never denied, but to the violence supposedly committed by someone else afterward.

It ought to be obvious from the above that Soering’s 1986 confessions were accurate and voluntary, and that nothing Soering says about his case can be trusted. This is why Soering’s supporters move briskly to other theories less dependent on Soering’s credibility. The most important of these alternate theories posits that unknown persons killed the Haysoms. The first problem with the mystery-killer theory is, of course, Mortal Thoughts itself, which claims that Elizabeth personally killed her parents in a drug-fueled frenzy. Yet shortly after Mortal Thoughts was published, Soering’s lawyer discovered that two drifters named Shifflett and Albright had killed and sexually mutilated a fellow drifter in the same general time and place as the murder of the Haysoms. Soering’s lawyers filed an appeal claiming that the prosecution should have notified the defense team of this fact. However, there was no reason why they should have done so; there was no evidence Elizabeth Haysom knew either of these drifters, or that the drifters had any connection to the Haysoms. The speculation from Team Soering was apparently that Elizabeth must have somehow met these drifters and managed to convince them to risk execution for no reward, since none of the valuables or alcohol in the home were taken. The Virginia Supreme Court dismissed this theory curtly: “[T]here is no connection whatever between Albright and Shifflett and the Haysom murders.”

The first attempt to conjure male accomplices thus fizzled. The next effort came in 2011, when a Lynchburg auto repairman named Tony Buchanan came forward to state that, 26 years beforehand, a woman who resembled Elizabeth Haysom had visited his transmission-repair shop with an unknown young male who definitely wasn’t Soering. The pair brought along a towed car with a broken transmission whose interior, Buchanan recalled, was bloody and contained a knife. This happened “several months” after the Haysom murders, according to Buchanan. Killing for Love inexplicably devotes considerable time to Buchanan’s story, even visiting him at home and showing him unidentified photos of Elizabeth Haysom’s mystery companion. But as with all of the “new facts” Team Soering has uncovered, this one raises more questions than it answers. First, why would Elizabeth Haysom have left a broken-down car filled with evidence which could send her to death row lying somewhere (where?) for months? And why then personally bring the car, still filled with that evidence, to a complete stranger to repair? Why, for that matter, did Buchanan wait 26 years after the most famous murder in Lynchburg history to come forward with his story? Even assuming any of these questions had answers, there is the issue of Buchanan’s credibility: When interviewed by New Yorker reporter Nathan Heller, Buchanan pointed a pistol at Heller, then claimed that Elizabeth’s mystery accomplice looked like Heller himself. Buchanan had also doodled “crazy droopy hair” on the comparison photos he had been given.

So much for the second attempt to find proof of male accomplices. The third attempt seemed more convincing, at least at first glance. While going over his case records Soering noticed an anomaly. Several samples of Type O blood had been found at the crime scene. In 1985, forensic DNA testing did not exist, only blood typing was available. Soering had Type O blood, like 40 – 45 percent of the U.S. population in 1985. Since Derek Haysom had Type A blood and Nancy Haysom had Type AB (Elizabeth has Type B), the Type O bloodstains were cited by the prosecution as being consistent with Soering’s presence at the crime scene. In 2005, Virginia launched an ambitious new program to test DNA in old cases. When Soering’s case was up for review, in 2009, the results were originally considered unspectacular: Only 15 percent of the badly degraded crime-scene samples yielded any testable DNA, and none of the profiles was complete. The partial profiles did not match Jens Soering. All of the partial profiles matched each other, though, so the lab worker classified them as probably containing the DNA of Derek Haysom. This would be logical, since Haysom had bled copiously everywhere. But Soering later noticed an anomaly: Some of the DNA samples with male DNA had come from crime-scene samples which, in 1985, had been classified as containing Type AB or Type O blood. This meant, according to Soering and two experts hired by his defense team, that there really were two unidentified men at the crime scene: Both of them were male (according to the DNA tests), and one of them had Soering’s blood type, but not Soering’s DNA, while the other had Nancy Haysom’s blood type, but was male and did not have Soering’s DNA.

This conclusion was not based on any new testing, only on a cross-correlation of existing reports, one from 1985 and one from 2009. Nevertheless, Team Soering proclaimed that they had physical evidence that someone besides Soering and the victims had been at the crime scene. Soering’s lawyer filed a petition for an absolute pardon with the Governor of Virginia citing new evidence of “actual innocence.” It was reports of these DNA results which originally attracted Wright and Beever’s attention.

Yet the DNA claim also collapses under scrutiny. Wright devotes almost 100 pages to the DNA/blood typing issue, discussing each individual sample at length. Wright identifies the critical flaw in Team Soering’s analysis: It conflates blood-typing test results with DNA test results. DNA and forensic blood-typing tests (which have long become obsolete) use different procedures to measure different values with hugely differing degrees of sensitivity. Reviewing the files, Wright observes that there were nine crime-scene samples which had too little blood on them for full typing in 1985, but yielded DNA results in 2009. Conversely, there were eight samples which had visible blood on them sufficient for full typing, but yielded no testable DNA.21 These differences between DNA and blood typing make the possibility of contamination critically important, since DNA tests are exponentially more sensitive than blood-typing tests. And contamination was inevitable: Soering bled profusely from a wound to his left hand, and engaged in a hand-to-hand fight to the death with two people. Blood, sweat, saliva, and bits of tissue from all of those involved were mixed and smeared together everywhere, and dripped from Soering’s knife. Even if it had been possible to prevent contamination during collection, it could have happened during storage: The crime-scene samples from his case had been simply stuck randomly into the court files and left to molder in warehouses for decades.

But the final blow to the “DNA-exoneration” theory is dealt by an analysis of the DNA itself. None of the four partial male profiles cited by Team Soering came from unknown donors; all were consistent with Derek Haysom’s DNA. What had happened was that, by 2009, the only remaining testable DNA in crime-scene samples originally typed AB and O had degraded except the DNA of Derek Haysom, which got there by cross-contamination. This explains why the two independent experts who reviewed Team Soering’s claims, Betty Layne DesPortes, former President of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences and Professor Dan Krane of Wright State University (who was hired by the American news program 20/20), both concluded that the test results neither confirmed Soering’s presence at the crime scene nor pointed to the presence of any unknown third party. Krane observes bluntly that the samples Soering’s experts claim for the unknown males “had the same DNA profile as Derek Haysom.” A German blogger with a biology background calculated the odds that all of these identical DNA partial profiles could have come from two unknown people (rather than from Derek Haysom) as 1 in 68 billion.

The last noteworthy development before Soering’s release concerned a few clues pointing to an FBI profile, another topic explored at length in Killing for Love. Rumors had circulated for years about an FBI profile created early in the case which allegedly pointed to a female who was “close” to the Haysoms as a potential suspect. In 2018, the theory received a minor boost when a Freedom of Information Act request led the FBI to release an anonymous Telex containing a summary of the investigation as of May 8th, 1985 which erroneously mentions an FBI psychological profile. Team Soering loses no opportunity to highlight the supposed FBI profile, doubtless hoping to conjure a connection to the innumerable television shows and movies in which profilers use ingenious psychological subterfuge to solve the most difficult crimes. The problem in Soering’s case: No FBI profile exists. As noted above, an FBI profiler named Ed Sulzbach did visit the crime scene, and composed a few notes, but no report. The FBI is notorious for keeping meticulous records; in Wright’s words: “If a profile had been written I can guarantee that the FBI would have kept a copy of it.”22Wright should know, having worked at FBI headquarters. Even if a report had been prepared, it would have had no effect on the trial, since psychological profiles are full of guesswork and speculation, and therefore not admissible in court.

Act Five: Freedom and One Last Volte-Face

This article, as long as it is, only scratches the surface of the supposed irregularities Team Soering cites. There’s also the issue of the “junk science” of the bloody sockprint, the biased judge, and the incompetent defense lawyers, to cite just a few additional examples. Wright demonstrates that all of these claims are based on exaggerations, inaccuracies, and sometimes outright lies, but even summarizing Wright’s arguments would turn this article into a treatise. In any event, as Wright notes, nearly all of these issues were examined by experienced state and federal appeals judges and dismissed decades ago, without a single dissenting vote. All of Team Soering’s theories suffer from the same weakness: They are less than the sum of their parts, because they point in different—and often conflicting—directions. Soering’s case is a textbook example not of a wrongful conviction, but of a false wrongful-conviction claim.

Meanwhile, Soering continues to change his story, even after being released from prison. In a long interview published on February 28th, 2020 by the German news magazine Der Spiegel—an interview conducted in the presence not only of Soering’s lawyer but also his PR consultant—Soering now claims that he “doesn’t know” who killed the Haysoms. This is odd, since Soering’s German-language book Not Guilty, still on sale all over Germany with a new post-parole foreword by Soering himself, states that Elizabeth Haysom killed her own parents. Doubtless, Soering’s lawyer gave him some pre-interview advice: Stop blaming Elizabeth. After all, you’re not the only one who can hire a lawyer to protect your reputation.

Why is the task of discrediting Soering’s claims important? Because the public has only so much concern and resources it can devote to people who were unjustly convicted. This bandwidth should be channeled to cases which genuinely merit re-investigation. Soering convinced dozens of well-meaning people to waste thousands of hours in a futile quest to prove his innocence. This effort could have been used to advocate for someone who was genuinely innocent—I would cite the inspiring counter-example of the second season of American Public Radio’s In The Dark podcast, which methodically demolished the case against Mississippi death row inmate Curtis Flowers.

How did Soering persuade his followers? Firstly, with sheer persistence: For decades, Soering devoted his wit and invention to inventing the most convincing alternate history he could manage. Soering also molded his claims to fit the zeitgeist. In the 1990s and early 2000s, exonerations of convicted criminals based on DNA testing showed that American courts had sentenced hundreds of innocent people to long prison terms or even to death. These findings shook the foundations of the American justice system, and sparked calls for reform. Soering tries to piggyback on the main sources of these wrongful convictions: false confessions, oversold forensic evidence, and police intimidation. Soering also benefits from the complexity of his case. To understand why his arguments fail, you’ve got to dive into moldering court files, and who has the time for that?

This is why the True Report is a vital corrective. It will never be made into a documentary, but its analysis will convince anyone who’s not already in the tank. The report also furnishes lessons for evaluating innocence claims from prison. First, false confessions are extremely rare. The risk of a false confession needs to be considered when dealing with suspects who are mentally ill, cognitively impaired, or who have been isolated, pressured, or tricked—but none of these conditions applies to Soering. To be sure, Soering “recanted” his confession, but every day, all over the globe, suspects recant confessions after realizing how much trouble they got themselves in. “Confessor’s remorse” is legally irrelevant: If the confession was voluntary and corroborated, it is good evidence, period.

The True Report also counsels us to pay attention to judges. Most of Soering’s claims have already been considered and rejected by experienced appellate judges. Of course, appeals courts can make mistakes, but, as with false confessions, they are rare. If they weren’t, why would we spend millions training and paying judges? If a prisoner enjoys a fair chance to convince judges his trial was unfair, and—like Soering—fails every time with every judge, his claims are probably insubstantial. Finally, the True Report reminds us to go beyond the buzzwords. DNA evidence can be powerful, but its value depends on the quality of the samples, how carefully the tests were conducted, and how the DNA evidence fits into the overall pattern of evidence. Psychological profiles make for fascinating television, but are inadmissible in court and for good reason, since there is no evidence of their general accuracy.

Jens Soering is now free. I personally wish him the best in re-adjusting to life in Germany. He still seems committed to some version of his innocence story, and will doubtless find many Germans to join with him within his bubble of delusion. Yet Elizabeth Haysom shows us the only honest and humane way to expiate guilt for a horrific crime. She pleaded guilty, accepted her sentence, expressed genuine remorse and anguish for her role in the murder of her parents, never sought publicity, and spent her time in prison finishing her education and doing good works. She can look forward to living the second half of her life in a spirit of redemption and reconciliation. Soering, on the other hand, will be pursued by the nemesis of his threadbare innocence story every time he opens his mouth—unless and until he, too, decides to acknowledge the truth, and set himself free.

UPDATES: After returning to Germany, Soering received six-figure advances from Netflix and a major German publisher for the rights to the story of his case. However, after questions were raised about his innocence story based on the Wright report and my articles, Soering deleted all his social media accounts in June 2020 and has made no public appearances or statements since that time. The status of the book and Netflix projects is unclear.

In late 2020, the Virginia-based investigative journalism podcast Small Town Big Crime obtained DNA samples from the two drifters implicated by Soering supporters as possible alternate suspects in the murders of Derek and Nancy Haysom and compared them to male DNA found at the crime scene. They were excluded. The podcasters also obtained a DNA sample from a relative of another alternate suspect often cited by Soering supporters, Jim Farmer. He was also excluded. After initially cooperating with the podcast, both Soering and his lawyer Steven Rosenfield refused all further cooperation with the podcast after these revelations. In January 2021, the German prosecutor who took Soering’s confession in December 1986, Bernd Koenig, gave an interview to a German podcast in which he confirmed that he had “no doubts at all” that Soering’s confession was accurate.

The Mississippi death row inmate mentioned in the article, Curtis Flowers, was exonerated of all charges on September 4, 2020, based in large part on facts uncovered by Season 2 of the APM Reports podcast In the Dark.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this essay incorrectly stated that “By the time authorities requested videotapes of the surveillance cameras from the Marriott Hotel, the tapes from the night of the murders had already been re-recorded.” The footage was not in fact recorded at all in 1985, it was monitored in real time by security. Apologies for the error.

References:

1 A True Report on the Facts of the Investigation of the Murders of Derek and Nancy Haysom by Terry Wright, p. 179.

2 Ibid., p. 4.

3 Ibid., pp. 152–58.

4 Mortal Thoughts by Jens Soering, p. 66.

5 Ibid., p. 67.

6 Ibid., p. 201.

7 Ibid., p. 69.

8 Ibid., p. 136.

9 A True Report on the Facts of the Investigation of the Murders of Derek and Nancy Haysom by Terry Wright, p. 150.

10 Mortal Thoughts by Jens Soering, p. 170.

11 A True Report on the Facts of the Investigation of the Murders of Derek and Nancy Haysom by Terry Wright, p. 166.

12 Ibid., p. 304.

13 Ibid., p. 331.

14 Ibid., pp. 298–299.

15 Ibid., p. 363.

16 Ibid., p. 213.

17 Ibid., p. 180.

18 Mortal Thoughts by Jens Soering, p. 136

19 A True Report on the Facts of the Investigation of the Murders of Derek and Nancy Haysom by Terry Wright, pp. 173–183.

20 Ibid., p. 179.

21 Ibid., pp. 27–29.

22 Ibid., p. 347.