United Kingdom

How the Trans Pledge Damaged the Labour Party

All told, it seems the trans pledge resulted in Labour losing 2.5 times more people than they gained from other parties: hardly a good trade.

Is political correctness just a storm in a campus teacup? Not if its effects ripple through the concrete structures of society, leading to major consequences.

Consider PC’s effect on the electoral fortunes of the mainstream Left. Centre-left parties are struggling across the West, and one reason is their “cultural turn” away from economic issues toward the politics of identity. Yet their inability to adapt to electoral realities is not just ideological, but exacerbated by a political correctness which hands radical activists the ability to silence dissent. This stymies efforts to move to the centre on cultural issues, leads to a doubling down on progressive stances, and powers ideological purity spirals. The result, as we shall see, leaves swing voters feeling cold.

In the US, centre-left commentator Noah Smith argues that the “woke” Democratic candidates–Beto O’Rourke, Kirsten Gillibrand, Julian Castro, even Kamala Harris–did poorly in the primary, flaming out relatively early. Only Elizabeth Warren remains, and her performance in the polls has been lacklustre. Whether wokeness is strong enough to shackle frontrunners like Bernie Sanders, and therefore harm his chances with the wider electorate, remains to be seen.

Blowback effects

The aforementioned observations gain credence from academic research. An emerging body of work in political psychology focuses on how blowback against political correctness tends to increase resistance to progressive policies and heighten the popularity of populist right candidates. One study, by Lisa Legault and colleagues, found that asking whether a group of students agreed or disagreed with the following statements led them to become more prejudiced than another group of students who did not see the statements:

- It is socially unacceptable to discriminate based on cultural background.

- People should be unprejudiced.

- I would be ashamed of myself if I discriminated against someone because they were Black.

- I should avoid being a racist.

- I would feel guilty if I were prejudiced.

- Prejudiced people are not well liked.

- People in my social circle disapprove of prejudice.

Research by Duke University’s Ashley Jardina finds that using the phrase “racist” when describing confederate statues or Donald Trump increases support for both among a segment of the electorate.

In Britain, the Labour leadership election is underway, with three candidates–Rebecca Long-Bailey, Keir Starmer and Lisa Nandy–contending for the role. Of the three, Long-Bailey and Nandy both signed up to the Labour Campaign for Trans Rights pledge, which led to heated debate both inside and outside the party.

What, I wondered, might the response of potential Labour voters be to news of the pledge? To find out, I ran a small survey of 214 people on the Prolific Academic survey platform on February 23rd. These online survey platforms are widely used in political psychology research, and give a good answer to the question of how the views of subgroups in a sample differ from one another. These samples tend to skew young and left, but there is plenty of diversity in the respondents to test hypotheses.

The study

In the study, I had half the respondents–the “control” group–read nothing, then asked them how likely they were to vote Labour.

Another half–the “treatment” group–first read a paragraph of text, derived from an article in the Morning Star of February 12th, 2020:

“Rebecca Long Bailey and Lisa Nandy have backed a 12-point plan put forward by the Labour Campaign for Trans Rights group that calls for sex-based rights campaigners to be expelled from Labour. Angela Rayner and Dawn Butler, who are in the running for deputy leader, also backed the group’s pledges. The trans rights group is calling for long debated changes to the Gender Recognition Act that would allow people to formally self identify as the opposite sex without paying for a certificate or demonstrating that they have accessed transitioning services. It also vows to ‘organise and fight against transphobic organisations such as Woman’s Place UK, LGB Alliance, and other trans exclusionist hate groups.’”

People were then asked whether they agreed with the pledge. Then they also answered the question about how likely they were to vote Labour.

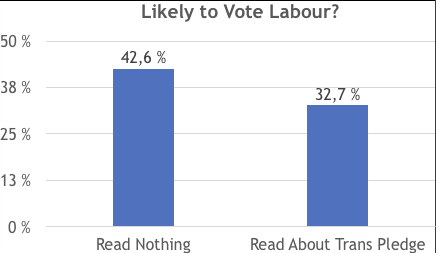

The results show that being exposed to even this small snippet of news about the pledge seems to reduce support for Labour. As figure one reveals, the share of survey respondents who said they would likely vote Labour was 42.6 percent among those who read nothing and just 32.7 percent among those who read the paragraph about the Labour trans pledge.

One reason for the drop was the limited popularity of the trans pledge among many survey respondents. For instance, less than a third of this mainly left-leaning sample who read about the pledge agreed with it. Among Labour voters, agreement rose to 40 percent, with 18 percent opposed and the rest undecided. However, Green, Liberal Democrat and Scottish National Party (SNP) voters split fairly evenly between opposing and supporting the pledge, with many undecided.

It seems that most opposed the pledge or were undecided. Among the 40 people who agreed with the pledge, 70 percent said they planned to vote Labour. Among the 99 who either disagreed or were unsure about the pledge, just 20 percent planned to do so.

Tellingly, even among those who voted Labour in 2019, 15 of the 33 respondents who opposed or were unsure about the pledge said they would not back Labour next time compared to all 22 respondents who both voted Labour in 2019 and backed the pledge.

Meanwhile, among those who didn’t vote Labour in 2019, just 21 percent backed the pledge. And among this small group of 18 pro-pledge Lib Dem, Green or SNP voters, only six people said they would switch to Labour.

All told, it seems the trans pledge resulted in Labour losing 2.5 times more people than they gained from other parties: hardly a good trade.

Moreover, Britain’s electoral arithmetic weights the socially conservative “Red Wall” seats of the North and Midlands more than the progressive cities and college towns. Ex-Prime Minister Tony Blair clearly revealed his exasperation with the pledge when he opined: “If you go, ‘Transgender rights are our big thing,’ and the right say, ‘Immigration control is our big thing,’ you are going to lose that war, so you are not going to advance any of the things you want to do.”

For Labour to have lost so badly and to have immediately indulged in a politics of progressive virtue-signaling raises the question of whether they are serious about returning to power.

It also points to the broader problem of highly-organised progressive networks like the trans rights lobby leveraging taboos around minority sensitivity to amplify their influence. This permits them to advance unpopular platforms that both weaken the Left and contribute to cultural polarisation.