History

Holbrooke and the 68ers

Our Man tells a tidier story than The Unwinding because it focusses on one man, and the analogy between Holbrooke and the country he served holds up remarkably well throughout the book.

Our Man—Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century by George Packer, Knopf, 608 pages, (May 2019)

Power and the Idealists by Paul Berman, W. W. Norton and Company, 348 pages, (April 2007 Reissue)

I.

George Packer is a shrewd chronicler of American decay. In his 2013 book The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New America, Packer reveals a battered, post-recession United States—from gutted factories in Youngstown, Ohio to abandoned housing developments in Tampa, Florida. The Unwinding isn’t a polemic—it’s written in the style of John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. trilogy, so it includes long profiles of the main “characters” alongside shorter essays about major American figures (from Colin Powell to Oprah) and page-long, staccato blasts of ads, lyrics, movie quotes, and headlines over the years.

While some of the portraits in The Unwinding are evocative accounts of American resilience and ingenuity, if you pick up the book today, it’s like reading the prequel to Trumpism. And it hasn’t escaped Packer’s notice that his most recent book, Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century, could be read as a companion to The Unwinding. As the subtitle suggests, Our Man is a book about American decline. But instead of telling the story with a wide cast of characters, Packer builds it around a single life and its intersections with the past 50 years of American history.

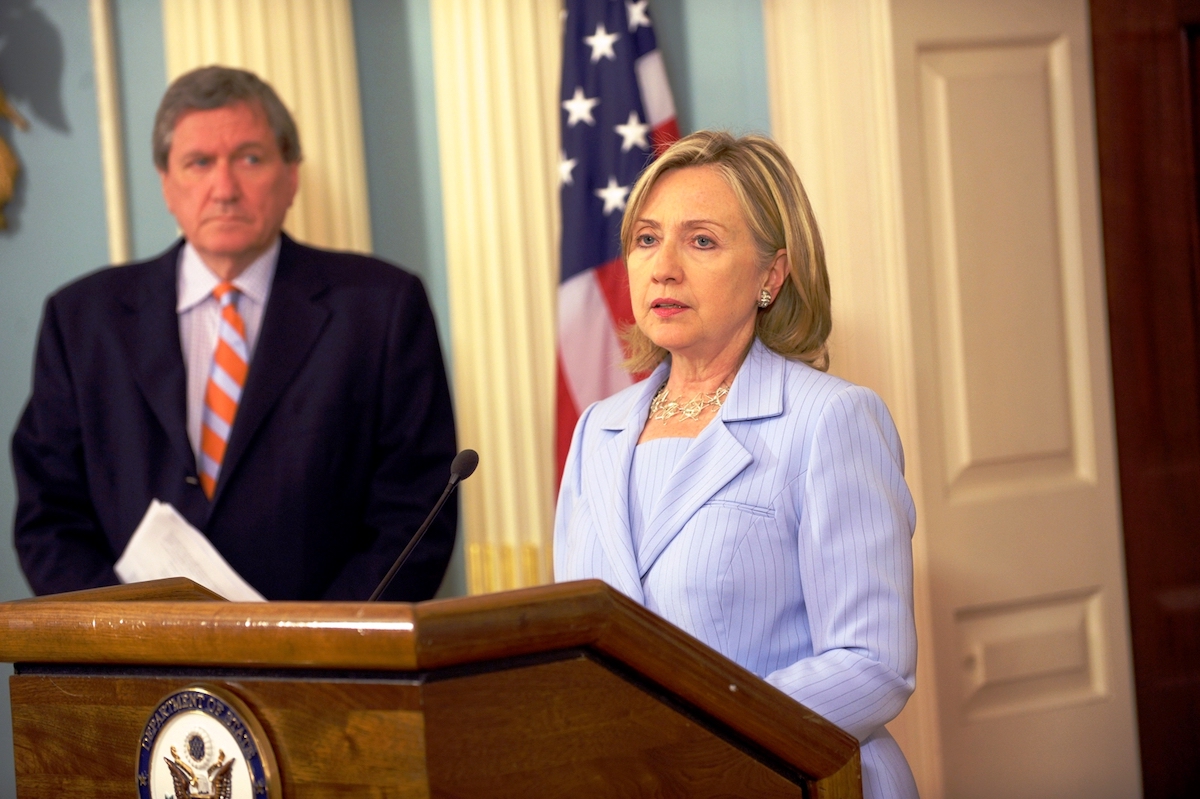

Holbrooke served in every Democratic administration from Kennedy to Obama. His career as a diplomat began in Vietnam, peaked when he negotiated an end to the Bosnian War at Dayton, and ended in Afghanistan. “It seems inevitable now that he would end in Afghanistan,” Packer writes. “There’s a final circular logic to it.” Holbrooke agreed, writing to himself after he was appointed the Obama administration’s special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan: “It is beyond ironic that 40+ years later, we are back in Vietnam.” According to Packer, the story arc of Holbrooke’s life roughly aligns with the trajectory of American power: “Pax Americana began to decay at its very height,” he writes—a few years before 9/11 and a few years after Dayton.

Our Man isn’t a dry summary of Holbrooke’s career, and it’s certainly no hagiography. Packer records his subject’s repeated betrayals of friends, colleagues, and wives, his rocket-propelled social climbing, and his strange blend of anxiety, vulnerability, and stratospheric self-regard (has anyone else in history personally lobbied for a Nobel Peace Prize?) in intimate and excruciating detail. He argues that Holbrooke was almost great—the traits that accounted for his ascension to greatness were inextricably tied to the weaknesses that confined him to the antechamber of almost-greatness. His ambition could shade into vanity and disloyalty, his “demon energy” could make him overbearing and exhausting, and his persistence—integral to his formidability as a negotiator—could poison his personal relationships.

But Holbrooke was also, as Packer tells us, “that rare American in the treetops who actually gave a shit about the dark places of the earth.” As a young foreign service officer, he saw through the official lies in Vietnam and wasn’t afraid to tell his superiors the truth. He played a critical role in ending the war in Bosnia. He fought to secure assistance for refugees at a time when almost nobody else would. Despite his betrayals, he also could be unwavering in his loyalty (particularly to members of his staff, as Packer often observes in talks about Our Man).

Packer argues that, like Holbrooke, the United States’ strengths have always been bound up with its weaknesses, especially since World War II: “The best about us was inseparable from the worst. Our feeling that we could do anything gave us the Marshall Plan and Vietnam, the peace at Dayton and the endless Afghan war. Our confidence and energy, our reach and grasp, our excess and blindness—they were not so different from Holbrooke’s.” Our Man tells a tidier story than The Unwinding because it focusses on one man, and the analogy between Holbrooke and the country he served holds up remarkably well throughout the book. But in keeping with Packer’s theme of duality, the coherence of the story—a story about inexorable decline; a kind of national entropy—is its biggest strength and biggest weakness.

To Packer, the end of the American century isn’t just a geopolitical fact about a rising China and the final hours of what international relations scholars describe as the United States’ “unipolar moment.” It’s the end of an idea—the idea that what’s sometimes described as the “postwar international order” has made the world freer and more secure. Packer explains: “What’s called the American century was really just a little more than half a century, and that was the span of Holbrooke’s life. It began with the Second World War and the creative burst that followed—the United Nations, the Atlantic alliance, containment, the free world—and it went through dizzying lows and highs, until it expired the day before yesterday.”

Our Man is a story about loss—the loss of America’s faith in itself and in the ideas that shaped Holbrooke’s era. “Now that Holbrooke is gone,” Packer writes, “and we’re getting to know the alternatives, don’t you, too, feel some regret? History is cruel that way.” What alternatives does he have in mind? The insularity and xenophobia of America Firstism. The amoral realism of Henry Kissinger, which doesn’t care about the dark places of the Earth. The idea that the United States is a bullying imperial power—the opposite of a force for liberalism and democracy and human rights.

But Packer is so focused on the cruelty of history that he fails to see its possibilities. While American power has waned, it remains unrivaled. While the Atlantic alliance has frayed, it remains intact. While the American century is coming to an end, there was nothing uniquely American about its animating ideas. And as long as those ideas haven’t expired, the institutions they built will survive. That’s what Holbrooke believed, anyway.

II.

If Packer is a historian of the American century, Paul Berman is a historian of the generation that lived through that century. His books A Tale of Two Utopias and Power and the Idealists trace the intellectual lineage of ideas that divided and defined the postwar world—a decades-long political and philosophical debate that spans the Western world and continues to this day.

The subtitle of A Tale of Two Utopias is: “The political journey of the generation of 1968.” In the United States, the images of 1968 are burned into our national memory: the chaos at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago, the riots after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Saigon as a warzone during the Tet Offensive. It was a period of revolutionary upheaval around the world, and Berman summarizes the “visible aftermath”: “The student uprisings, the hippie experiments, the religious transformations, the rise of communism in some places and the first sign of its fall in other places, the Black Power movement, and onward through feminism and every insurrectionary impulse of the age … rebellions in the ‘68 style,” he continued, “became a kind of ritual, year after year.”

But Berman also discusses what he describes as 1968’s invisible aftermath—an “undertow of analysis and self-criticism among the rebels themselves.” There was plenty to be self-critical about, from the radical violence of groups like the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground (“guerrilla armies were popping up everywhere you looked in those years,” Berman notes) to the “anti-imperialism” that took the form of Soviet, Castroite, Maoist, and Minhist propaganda. While many of the bizarre idiosyncrasies and deformations of the 1968 generation seem farcical now, Berman reminds us that there’s much to mourn in a “movement for freedom and solidarity that turns into a movement for tyranny and violence.”

However, Berman explains that “those long-ago utopian efforts to change the shape of the world were a young people’s rehearsal, preparatory to adult events that only came later.” The self-critical radicals kept at it, and all around the world the “drift was more or less the same”: away from the radical deformations and toward liberal democratic principles and institutions. “Beginning in 1989,” Berman writes, “to universal astonishment, the forgotten genie from 1968, a world revolution, flew out from a bottle.” The 68ers’ journey had taken them from the ideas that kept the Iron Curtain drawn to the ideas that would ultimately tear it down.

What were those ideas? Among the most important was anti-totalitarianism. This was a difficult principle for dissidents and revolutionaries to uphold because it made support for many left-wing regimes and movements impossible. Worse still, any 68ers who denounced violent oppression in the Soviet Union, Cuba, or North Vietnam could be accused of aligning themselves with the United States. But this wasn’t such a huge problem for some unorthodox 68ers—particularly from Eastern Bloc countries—for whom the “old animosity for the United States,” Berman writes, “dropped away.” While Czech President Václav Havel originally identified with the anti-imperialist critique of the United States that was so common among the 68ers (particularly in the West), Berman points out how the brutal realities of the Soviet system changed his mind: “For what did those Western peaceniks, his own comrades, know about living in a Soviet-style totalitarian state? About spending year after year in a communist prison?”

While Havel is among the best-known 1989 revolutionaries, his insights about the hypocrisy of the Western peaceniks and the nature of Soviet tyranny didn’t occur to him in a vacuum—they were the product of his own experiences plus two decades of vigorous debate about resistance, imperialism, and authoritarianism. This debate is at the center of Power and the Idealists, and as the title suggests, Berman demonstrates how anti-totalitarian theories that were developed in the 1970s and 1980s became anti-totalitarian policies in the 1990s and 2000s.

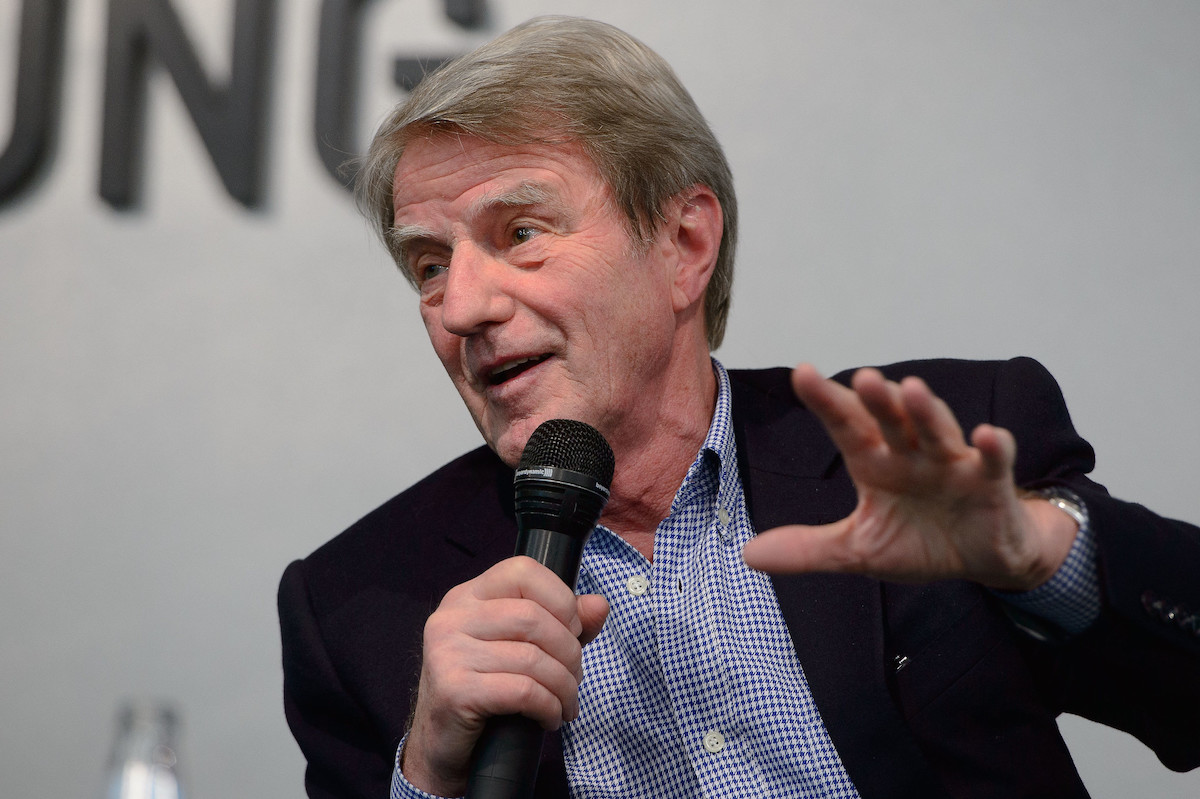

The three main figures in Power and the Idealists are Joschka Fischer (who served as German foreign minister and vice chancellor from 1998 to 2005), Daniel Cohn-Bendit (who became leader of the European Parliament’s Green Party in 2002), and Bernard Kouchner (who founded Médecins Sans Frontières in 1971). Like Berman, all of these men took part in the insurrections of 1968 and remained radical activists into the 1970s. But in one way or another, all three ended up arriving at many of the same conclusions as Havel: Radicals had no business supporting communist dictatorships (or dictatorships of any kind); NATO could be a force for democracy and human rights; and internationalism should be more than a political slogan for organizing workers of the world—it should mean support for refugees, the victims of atrocities, and anyone else who needs assistance. It should even sometimes call for cooperation with the United States.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, these ideas were refined and popularized by a group of European (particularly French) intellectuals and philosophers, such as André Glucksmann, Bernard-Henri Lévy, Alain Finkielkraut, and Pascal Bruckner. This political shift in Europe was a consequence of many factors: Horror at the massacre of Israeli athletes in Munich and the Entebbe hijacking of an Air France flight by Palestinian terrorists and German radicals; the publication in 1973 of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago, which shattered many left-wing delusions about the Soviet Union and severed factions of the Left happy to make accommodations with totalitarianism from those that weren’t; and the abundant evidence that the various forms of “new” communism in Latin America, China, and Vietnam were every bit as corrupt and oppressive as the old ones in Russia and Eastern Europe.

This evolution wasn’t the same for everyone—as some factions of the European Left struggled to reconcile their old principles and affiliations with their nascent anti-totalitarian ideas in the 1970s and 1980s, Bernard Kouchner was already putting those ideas into action. As a young man, Kouchner had been a member of the French Communist Party, and had even spent an evening with Fidel Castro during a trip to Cuba in 1964. But when thousands of Vietnamese fled their violent and repressive communist government in the late 1970s, Kouchner organized the “Boat for Vietnam”—an international effort to rescue as many refugees as possible, who often drowned when their flimsy, overcrowded vessels sank in the South China Sea. According to Berman, many on the “orthodox Left” regarded the Boat for Vietnam as “blatantly and unmistakably reactionary—a retrograde humanitarianism that might succeed in rescuing a few people but was also bound to inflict a political blow on Indochina’s best hope for progress in the future, namely, the communists.”

But Kouchner had no time for the armchair radicals who criticized him from the comfort and safety of Western countries while celebrating thugs and murderers like Che Guevara and their futile campaigns to incite worldwide revolution. Berman observes that Kouchner was launching a different kind of revolution—a “Guevarism of the rights of man.”

This was the impulse behind the founding of Médecins Sans Frontières (better known as Doctors Without Borders in the United States). “Kouchner’s idea,” Berman writes, “was to create an emergency humanitarian group capable of reacting to crises around the world quickly and flexibly, and yet capable also of reporting on whatever the volunteer workers might happen to see … a more political Red Cross.” After an earthquake hit Managua, Nicaragua in 1972, Médecins Sans Frontières sprang into action for the first time, and Berman makes quick work of the pseudo-revolutionaries who “sneer at this sort of do-good operation, and go on plotting their ridiculous microwars.” Kouchner’s organization wasn’t shackled to any rigid doctrines or utopian fantasies—it existed solely to help people who needed it most.

Berman notes that Kouchner’s missions were “no less dangerous than any guerrilla struggle, no less frightening, no less difficult, but … had the great virtue, in contrast to a communist insurgency, of refusing to lie.” And that refusal led Kouchner to some unsettling conclusions. For example, Berman writes, “Maybe the power of the United States, with its navy and everything else, was a force that could be harnessed to good purposes.” This was a particularly incendiary view when it came to Vietnam, as most of Kouchner’s left-wing allies were viscerally opposed to any ongoing American involvement in Southeast Asia. And yet, Berman points out that Kouchner’s attempts to rescue the Vietnamese boat people led to a simple and inescapable conclusion: “If a rented ship from France was a good idea, the Sixth Fleet was a better idea.”

Thanks to Holbrooke, who was then in charge of East Asian and Pacific Affairs at the State Department, Washington arrived at the same conclusion. According to Packer, he “appeared before Congress and argued for admitting an additional fifteen thousand Vietnamese refugees” in August 1977: “‘The motivation is simple,’ he [Holbrooke] said: ‘the deep humanitarian concern which has for so long been a descriptive part of our national character.’”

Holbrooke also suggested using Navy ships to rescue refugees in distress in the South China Sea, and he solicited vital support from Vice President Walter Mondale. During a meeting in the Situation Room in the Spring of 1979, Mondale snapped at an admiral: “Are you telling me that we have thousands of people drowning in the open sea, and we have the Seventh Fleet right there, and we can’t help them?” The Pentagon didn’t like the idea of using destroyers to pick up refugees, but according to Packer, Mondale “told the admiral to carry out the mission or find another job.”

III.

Holbrooke’s career is a bridge between the ideas outlined in Power and the Idealists and major features of U.S. foreign policy after 1989. He wrote the preface to the 2007 edition, in which he observed that Berman had “identified the roots of an important development in post-Cold War thinking: a turn, among a small but influential group of the ‘68ers, away from some of the traditional left-wing and anti-American dogmas of the past in favor of a new kind of liberal anti-totalitarianism.” Holbrooke emphasized the impact of these ideas on “attitudes and policies from Cambodia and Vietnam to the East Bloc revolutions of 1989 and the Balkan wars of the 1990s.”

One 68er in particular is the dominant figure in his essay—Kouchner, who recognized early on that, as Holbrooke explained, it was necessary to “abandon his original ideas and attack equally crimes and totalitarianism of the Left and the Right,” and who “played an immense role in shaping a new view of intervention in the internal affairs of other nations.” Holbrooke was the American ambassador to the U.N. when Kouchner was in charge of the U.N. mission in Kosovo, and the two became close friends. The same principles that motivated both men to organize rescue efforts in the South China Sea in the late 1970s were behind their work in the Balkans two decades later. As Holbrooke put it, “Kouchner was called upon to implement his own theories.”

Holbrooke argued that Kouchner had “launched a movement” around a concept that became known as the “right to intervene” (which would be echoed in a later U.N. doctrine, “responsibility to protect”): “By the mid-1990s, after the horrible lessons of Rwanda and Bosnia, many nations, including ultimately the United States and the members of the European Union, began to find reasons to accept this new formulation and apply it to Bosnia (1995) and Kosovo (1999), where enormous numbers of people needed to be rescued.”

To the furious consternation of many of their left-wing allies, Joschka Fischer and Daniel Cohn-Bendit both supported the NATO intervention in the Balkans as well. After Fischer became Germany’s foreign minister in 1998, he immediately abandoned his party’s long and fervently held anti-war position and announced Germany’s support for the NATO campaign in Kosovo. The outrage was ferocious: “At a Green convention in 1999,” Berman writes, “someone threw a bag of red ink at Fischer and broke his eardrum. Four hundred police officers had to stand guard when he got up to address the convention. His own party, the eco-pacifist assemblage, was a howling mob.”

Although Cohn-Bendit didn’t suffer any busted eardrums, the antipathy for him in some left-wing quarters was equally intense. As a 2002 article in Politico noted: “Cohn-Bendit’s critics claim the former revolutionary has sold out for abandoning his revolutionary beliefs and advocating policies—such as military intervention in the Balkans—viewed as reactionary by his more radical colleagues.” But like Kouchner, Fischer and Cohn-Bendit were undeterred by the outrage and scorn of their left-wing colleagues—their political courage had pushed them toward a different kind of Left.

There’s a reason Power and the Idealists appealed to Holbrooke. He was an idealist, and while it would be an overstatement to describe him as “anti-totalitarian,” he was perhaps the quintessential example of what has come to be described (often derisively in the era of Iraq) as a liberal interventionist. As Packer explains: “He believed that power brought responsibilities, and if we failed to face them the world’s suffering would worsen, and eventually other people’s problems would be ours, and if we didn’t act no one else would.” He continues:

Does it sound softhearted and dreamy? Not at all. You could call it an updated version of the liberal internationalism of Roosevelt, Truman, and Kennedy. The enemies were now murky civil wars, second-rank tyrants, mass atrocities, failed states. Kissinger would not have recognized these as subjects of high national interest, but Holbrooke, never a practitioner of pure realpolitik, was alive to the present.

As Holbrooke observed, Kouchner was a liberal interventionist long before the idea had any serious support in the United States: “Since policymakers tend to be oblivious to the origins of new ideas, almost no one in Washington and few in Brussels realized that the intellectual roots of intervention in the Balkans came from a doctor, who at that moment was serving as the French Minister of Health.” Berman even claims that Kouchner “pretty much invented the concept of humanitarian intervention as something more than a once-in-a-blue-moon exceptional act.” He cites a series of U.N. resolutions Kouchner helped to develop, which authorized international actions in response to natural disasters and conflicts—resolutions that permanently changed the laws and norms around interventionism.

These resolutions weren’t just symbolic: “At the end of the first Gulf War,” Berman writes, “Kouchner helped draw up still another resolution, this time addressed to the Security Council, calling for military intervention into Iraq on behalf of the Kurds.” France proposed the resolution, the Security Council adopted it, and no-fly zones were promptly established by the United States and Britain over northern and southern Iraq. As Berman explains, “In this fashion, the legal record in favor of humanitarian interventions grew ever larger, until, by Kouchner’s count, some 350 resolutions had eventually been passed.”

The Gulf War itself forced the U.N., the United States, and the European anti-totalitarians to confront the fact that a genocidal dictator had invaded and attempted to annex a neighboring country. Cohn-Bendit declared his support for the war, despite the fact that, as Berman explains, his fellow Greens were “overwhelmingly and almost genetically antiwar.” Berman also points out that the “68ers from what used to be the Soviet bloc had no trouble at all supporting the war against Saddam.” Havel even sent a group of chemical warfare experts to join the U.S.-led Coalition forces, making Czechoslovakia one of almost 40 countries (including several Arab states) to participate. Unlike the Iraq War in 2003, the Gulf War also had U.N. authorization, and Saddam’s forces were expelled from Kuwait in a matter of months.

IV.

When Holbrooke was out of government in the early days of the Bosnian War, he traveled to the Balkans with the International Rescue Committee to see what was happening for himself. He visited a refugee camp in Karlovac, Croatia, where he met a man from Prijedor—a Muslim majority town that had been overrun by Bosnian Serb forces. Packer explains what happened in towns like Prijedor:

Following careful plans, the gunmen would surround the town, block the exits, and go house to house while local Serbs pointed out the Muslim and, in fewer cases, Croat families. The paramilitaries would send the residents out into the street, then loot and destroy the houses. Women, children, and old people were driven out of the town and forced to make their way to the relative safety of Croatia. Men were separated into groups. Those whose names appeared on lists of local notables were taken away and never seen again.

If you want a good summary of the excuses and half-measures on the Balkans by Western governments in the early 1990s—when the ethnic massacres were well underway—you couldn’t do much better than the relevant sections of Our Man and Power and the Idealists. Despite calling for airstrikes in Bosnia during the 1992 campaign, Clinton was extremely reluctant to get involved. He thought U.S. engagement in the Balkans was a bloody quagmire waiting to happen. Packer cites a call Les Aspin made to Anthony Lake and Peter Tarnoff after meeting with the president: “He’s going south on this policy. His heart isn’t in it.” The policy in question was called “lift and strike” because it would have lifted the arms embargo on Bosnia and authorized airstrikes to protect Muslims and other groups threatened by the Serbs.

In the era of Iraq and Afghanistan, we often hear about the hostility to U.S. action abroad and forget the contempt many Bosnians had for inaction in the Balkans. When U.N. Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali and U.N. special envoy Cyrus Vance visited Bosnia during the siege of Sarajevo, they were greeted with shouting protesters who held signs that read “We Need Weapons” and “Help Us or Go Home.” Packer quotes a young woman from a Sarajevo radio station who challenged Boutros-Ghali when he said foreign intervention would only cause more problems: “What do you want before you will do something? How many victims are needed before you act? Aren’t twelve thousand enough? Do you want fifteen or twenty thousand? Will that be enough?”

Packer also tells us about a reporter at Oslobodenje who was “burning his books in his fireplace to keep warm and writing in his diary, ‘Boutros Boutros-Ghali is here. When I hear his name, waves of hatred emerge from within me.’” Oslobodenje continued to publish from a basement underneath its bombed-out offices throughout the siege. “I cannot promise that you will be alive when the siege is over,” editor-in-chief Kemal Kurspahic told his staff when Serbian artillery started bombarding Sarajevo. “But I can promise you this: As long as Sarajevo exists, this newspaper will publish every day.” According to a New York Times report, by early October 1992, “Six staff members are dead and 10 have been wounded.” When Kurspahic was asked what message he had for the rest of the world, he said, “Only one—H-E-L-P. Tell the world we need Phantoms, we need Marines. Also the Sixth Fleet.”

Packer and Berman agree about the general trajectory of Western policy in the Balkans in the early 1990s. It began with what Berman describes as the “principle of non-action through action … a non-action that cannot be faulted because it calls itself action.” When Secretary of State Warren Christopher approached the United States’ European allies to discuss lift and strike, he said he was in “listening mode.” Like the president, his heart wasn’t in the proposal, and Packer summarizes how it was received: “Christopher invited the Europeans to answer as they did: We have troops in Bosnia, you don’t. Either put your men where your policy is or find another policy, because lift and strike is going to get our peacekeepers killed. Since Clinton had vowed never to send troops into the conflict, the U.N. mission became the prime reason to do nothing but stand by while the killing continued.”

A few months later, 19 American soldiers were killed and dragged through the streets in Mogadishu, and this made Clinton even more reluctant to get involved in messy conflicts on the other side of the world. As almost a million people were slaughtered in Rwanda over just three months in the spring of 1994 and the killing continued in the Balkans, the Clinton administration stood by. But after a year of political pressure from abroad (French President Jacques Chirac, who had just taken office, announced that the “position of leader of the free world is vacant” in June 1995), Clinton finally acknowledged that it was time to take more robust action. And in July 1995, Gen. Ratko Mladić’s forces slaughtered thousands of Muslims in Srebrenica—an atrocity that made greater U.S. involvement even more pressing. Packer mentions a conversation between Clinton and his national security advisors: “Our position is unsustainable. It’s killing the position of the U.S. in the world. This is larger than Bosnia.”

The Dayton Accords were Holbrooke’s greatest diplomatic achievement, and they couldn’t have been negotiated without the threat and use of American force. In early September 1995, two months before Dayton, NATO and the U.N. demanded an end to Mladić’s siege of Sarajevo and suspended the bombing campaign to give the Bosnian Serbs time to make a decision. “This was a moment when force and diplomacy had to be in perfect alignment,” Packer writes. The bombing was intended to prove to the Bosnian Serbs that NATO was serious about forcing an agreement, and if the siege of Sarajevo did not cease, air strikes would need to continue. Packer quotes a phone call between Holbrooke and the Situation Room: “If we do not resume the bombing, it will have lasted less than forty-eight hours. It will be another catastrophe. NATO will again look like a paper tiger. The Bosnian Serbs will return to their blackmailing ways.”

NATO bombers were in the air again the following morning, and within two weeks the Serbs agreed to end the siege of Sarajevo. Less than two months later, the Dayton Accords brought the Bosnian War to an end, proving that American power can put war criminals and ethnic cleansers on notice, protect people who desperately need protection, and prevent an entire region from collapsing into bloodshed. But there are other ways to view the legacy of Bosnia, as Packer acknowledges: “Some Europeans—some Americans, too—thought we took the wrong lesson from Bosnia: that America only had to throw its weight around to get results. These skeptics would draw a straight line from Dayton to Iraq, and in Holbrooke they saw the humanitarian face of American hubris.”

V.

Iraq was never a major interest of Holbrooke’s, as Packer explains: “Iraq was disintegrating—a war he’d like to have forgotten. He had no desire to see Baghdad for himself … Iraq was flat and hot and harsh, and every human touch, including ours, made it uglier.” During Holbrooke’s first and only personal meeting with Obama, which took place in Chicago days after the 2008 election, he told the president-elect where he was (and wasn’t) interested in working: “As for jobs,” Packer writes, “one position he didn’t want was Middle East envoy.”

Packer argues that Holbrooke supported the Iraq War for political reasons and urged Sen. John Kerry to do the same (he was hoping to be Kerry’s Secretary of State if he won in 2004). “If that was Holbrooke’s main reason for supporting the war,” Packer writes, “it might have been better to be stupidly, disastrously wrong in a sincerely held belief like some of us.” But was it just political expediency that led Holbrooke to support the Iraq War? In his preface to Power and the Idealists, Holbrooke lamented the “horrible, incompetent execution of American policy in Iraq” and argued that a “policy badly carried out becomes a bad policy.” However, criticizing the execution of a war isn’t the same as criticizing the reasons for going to war in the first place. Holbrooke worried that Kouchner’s anti-totalitarianism and interventionism had been disfigured in the post-9/11 era: “Have good new ideas led to bad results—in Iraq, above all?” He argued that “veterans of the New Left” who supported the war “hoped that, in spite of the unattractive qualities of the Bush administration, intervention in Iraq would end up resembling the intervention in the Balkans—a humanitarian policy with humanitarian results.”

When President Obama delivered his famous Cairo speech in 2009 (entitled “A New Beginning”), his critics attacked it as the headline event of an “apology tour.” Obama decried a history of “colonialism that denied rights and opportunities to many Muslims” and referred to a “Cold War in which Muslim-majority countries were too often treated as proxies without regard to their own aspirations.” But Obama’s critics didn’t seem to notice that Bush made a substantially similar point when, in a 2003 speech, he argued that “Sixty years of Western nations excusing and accommodating the lack of freedom in the Middle East did nothing to make us safe.” Obama and Bush differed dramatically on Iraq, of course, but they were both demanding a break from the status quo of Kissinger-style realpolitik in the region. Holbrooke understood this, which is why he recognized that some supporters of the Iraq War were motivated by “noble ideas” like resistance to the “arch-totalitarian Saddam Hussein.”

Of course, Holbrooke also understood that all the noble ideas in the world couldn’t change the fact that the Bush administration made a series of catastrophic mistakes in Iraq, such as de-Baathification (Berman usefully contrasts this policy with the decision to convert the Kosovo Liberation Army into the Kosovo Protection Corps, which offered “military prestige and a dependable salary to its soldiers” instead of throwing them out on the street). Nor do they absolve the Bush administration of its colossal errors of judgment and analysis—from the misplaced obsession with weapons of mass destruction to the failure to anticipate the strength of the insurgency or the level of sectarian violence that would be unleashed by the invasion.

Berman cites a particularly egregious example of bogus prophesizing from Richard Perle: “We have Ahmad Chalabi, chief of the opposition Iraqi National Congress, to enter Baghdad … We will hand over power quickly—not in years, maybe not even in months … I expect the Iraqis to be at least as thankful as French President Jacques Chirac was for France’s liberation.” Packer’s words—“stupidly, disastrously wrong”—come to mind.

Perle was debating Daniel Cohn-Bendit at an event in Washington, D.C. “Oh, come on,” the latter responded when Perle lectured him about Chalabi, liberation, and a war that would be over in weeks. Cohn-Bendit accused the United States of “behaving like the Bolsheviks in the Russian Revolution. You want to change the whole world!” A month earlier, when Donald Rumsfeld was making the case for war at a European defense conference in Munich, Joschka Fischer told him: “Excuse me, I am not convinced … I cannot go to the public and say these are the reasons [for war] because I don’t believe in them.” Holbrooke was sitting between the two men.

The Bush administration was guilty of “revolutionary hubris,” in Cohn-Bendit’s words. It had taken the liberal interventionist idea to a reckless extreme. As he put it, “I am no pacifist, and I know military intervention can be absolutely necessary,” which is why he supported the Western intervention in the Balkans. But protecting civilians and seeking a negotiated end to the conflicts in Bosnia and Kosovo was one thing—using the might of the U.S. military to foment what Bush described as a “democratic revolution” in the Middle East was something entirely different. The people who draw a straight line from Dayton to Iraq fail to appreciate these distinctions—they argue that the entire anti-totalitarian and liberal interventionist idea should be scrapped after Iraq. But no matter how many times the word “Iraq” is used as if it’s an argument in and of itself, history didn’t begin during the first term of the Bush administration.

VI.

When Packer argues that it’s time to get used to the “alternatives” to Holbrooke’s liberal interventionism, he’s identifying a real phenomenon. Iraq and Afghanistan have led to the most significant reassessment of U.S. foreign policy since the end of the Cold War. One of the reasons for President Trump’s popularity in 2016 was his declared hostility to the prevailing foreign policy establishment—he called for more restrained American action abroad and claimed to be focused on a strict interpretation of the United States’ national interest.

Aside from its noxious historical implications, this was the meaning of “America First” (a slogan Packer rightly despises). While Trump’s foreign policy has been far more inconsistent and interventionist than advertised (from large increases in the defense budget to the assassination of Gen. Qassem Soleimani and the “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran), his original message resonated with many Americans. On the Left, populist politicians like Bernie Sanders rail against “endless wars” and call for a more modest and less interventionist foreign policy. On the Right, libertarians like Sen. Rand Paul and paleoconservatives like the Fox News mega-pundit Tucker Carlson demand that Trump return to the isolationist ideas he promulgated during the campaign. So it’s not as if Packer is mistaken when he points out that the alternatives to liberal interventionism are ascendant.

But Packer also acknowledges that Americans’ relationship with the world doesn’t follow some linear progression toward a single endpoint: “We swing wildly between superhuman exertion and sullen withdrawal, always looking for the answers in our own goodness and wisdom instead of where they lie, out in the world, and in history.” Although Holbrooke was usually closer to the superhuman exertion end of that continuum, he was also, as Packer reminds us, alive to the present. That’s why his preface to Power and the Idealists cautions against both overextension and withdrawal; hubris and impotence: “We are going to have to find the proper balance between prudence, on one hand, and effective, calibrated involvement in the international arena on the other. We are going to have to ask ourselves difficult questions about matters of principle and matters of practicality.”

When the time came to discuss military action in Iraq, Kouchner had to ask himself what a principled and practical policy might look like. In an article in Le Monde, he called for “neither war nor Saddam.” He wanted the international community to force Saddam from power without a full-scale invasion, but he thought the threat of invasion was necessary. He wanted to apply military pressure gradually—by expanding the no-fly-zones in northern and southern Iraq, for instance. And as Berman explains, he was “furious that Bush didn’t make the pure humanitarian case.” He constantly emphasized Saddam’s most grotesque crimes, from the Halabja chemical attack to the wider Anfal genocide to the massacre of Kurdish and Shia rebels after the Gulf War. Berman points out that Kouchner “judged that a human rights and humanitarian argument would have carried weight in Europe, politically speaking.”

Meanwhile, Fischer and Cohn-Bendit were having their confrontations with Rumsfeld and Perle. They spoke for many of their fellow Europeans when they heard the arrogant and naive American predictions about a quick and easy war in Iraq and said, respectively, “I am not convinced” and “Oh, come on.” But Europe was with the United States in the Balkans. It was with us after we were attacked on 9/11 and our NATO allies invoked Article 5, volunteering to send their troops into harm’s way in Afghanistan. It wasn’t until Iraq that the United States’ superhuman exertion devolved into hubris and the liberal interventionist idea that Kouchner and Holbrooke had developed and implemented began to lose its appeal.

In Our Man, Packer asks: “The thing that brings on doom to great powers, and great men—is it simple hubris, or decadence and squander, a kind of inattention, loss of faith, or just the passage of years?” He could have added the failure to learn from history—not just the history of disasters like Vietnam, but the history of successful interventions, as in the Balkans, and responsibilities abrogated, as in Rwanda (which Clinton has described as the most agonizing failure of his presidency). While the United States should have listened when its European allies warned of revolutionary hubris in Iraq, it also shouldn’t flee its responsibilities as the most powerful liberal democracy on the planet. While Europeans have a better sense of history than Americans, it still took the U.S. Air Force to secure the peace at Dayton and prevent another explosion of ethnic bloodshed in Kosovo.

“It wasn’t a golden age,” Packer writes of the American century, “there was plenty of folly and wrong, but I already miss it. The best about us was inseparable from the worst.” Even Packer’s critics admit that he never obscures or ignores the folly and wrong. While Holbrooke did important work for refugees in Southeast Asia, he also supported the decision to hand Cambodia’s seat in the U.N. General Assembly to the Khmer Rouge when he was U.N. ambassador. While he played a crucial role in the passage of a U.N. resolution to send an Australian-led peacekeeping force to East Timor in 1999, Packer points out that he was also “trying to sell American fighter jets to Indonesia and overlooking its bloody annexation of East Timor” two decades earlier. The best and worst of Holbrooke—and of the country he served—were often in uncomfortably close proximity.

Fischer, Cohn-Bendit, and Kouchner would agree. They’re children of a generation that witnessed the near-collapse and reconstruction of Europe, with America leading the way. But their politics were forged during the catastrophe of Vietnam—a calamitous period of American hubris and failure. Unlike the Bush administration officials who thought they could remake the Middle East, they search for answers in history instead of their own goodness and wisdom, which may be one of the reasons why Holbrooke thought Power and the Idealists could “help build a broader, bipartisan consensus for an enlightened Atlantic foreign policy.” They have justified suspicions of the United States, but they understand that idealists like Holbrooke have done tremendous good in power. That’s history, too. But there’s nothing exceptional about the universal principles that guided Holbrooke and America when we were at our best—principles that were articulated so clearly and early on the other side of the Atlantic.

While Packer closes Our Man with a reflection on the cruelty of history, Berman emphasizes its possibilities. He argues that a new generation needs “new language for talking about some very old and wrenching and unresolvable arguments. About resistance, and collaboration, to begin with. About totalitarianism, and anti-totalitarianism. About liberal and humanitarian intervention…” Packer may be right that the end of the American century will inaugurate a new era of insularity and indifference toward liberal values like democracy and human rights—a kind of perpetual America Firstism. But the ideas that motivated Fischer, Cohn-Bendit, Kouchner, and, yes, Holbrooke haven’t disappeared.

Packer believes the architects of the American century—the “figures like Acheson, Kennan, Marshall, and Harriman” whose ranks Holbrooke spent his entire life trying to join—had a unique understanding of power and the responsibilities it brings. They were idealists: “They didn’t just grab for land and gold like the great men of earlier empires. They built the structures of international order that would endure for three generations, longer than anything ever lasts, and that are only now turning to rubble.” Packer appears to think those structures—and the principles that sustain them—are incapable of surviving the end of the American century. But there are a few radical humanitarians in the heart of Europe who would surely disagree.