Mars

Should We Colonize Mars? The Fate of Humanity May One Day Depend on It

Do we have the right to supplant Martian life with our own? Yes—because a human life has more value than that of a bacterium.

On October 21, U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) Administrator Jim Bridenstine told the House Committee on Science, Space and Technology that he foresees NASA will land astronauts on the moon by 2035. “We need to learn how to live and work in another world,” he told lawmakers. “The moon is the best place to prove those capabilities and technologies.”

The article that follows comprises the seventh instalment in “Our Martian Moment,” a multi-part Quillette series in which our authors discuss what kind of society humans should build on Mars if and when we succeed in colonizing the red planet.

Four years ago, at the 67th International Astronautical Congress in Guadalajara, Mexico, Elon Musk set out two possible paths for humanity. “One path,” he told his audience, “is we stay on Earth forever, and then there will be some eventual extinction event.” He was not foretelling immediate doom, just noting that nothing lasts forever. Inevitably, if humans stay long enough, we’ll suffer some sort of extinction-level disaster, similar to previous mass-extinction events encoded in the fossil record. The universe is a dangerous place, and the fact is that eventually our current run of good luck (about 66 million years and counting since the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event) will run out.

“The alternative,” he said, “is to become a space-faring civilization and a multi-planet species.” Which is to say: having more than one home for humanity would increase the odds that our species survives a disaster on Earth. It is therefore prudent to look around the solar system for a place to go. Mars is our best option.

Mars is (relatively) close, possesses an atmosphere (albeit a thin one composed mostly of carbon dioxide), exerts a surface-level gravitational force about 38% that of its terrestrial counterpart, along with a day length and axial tilt roughly comparable to those of Earth. Daytime temperatures, while low, sometimes can exceed the freezing point of water during the Martian summer at points near the equator. And evidence from NASA missions shows that there is at least 20 cubic kilometers of ice at or near the surface. All of this makes Mars a far more promising place to colonize and terraform than, say, our moon.

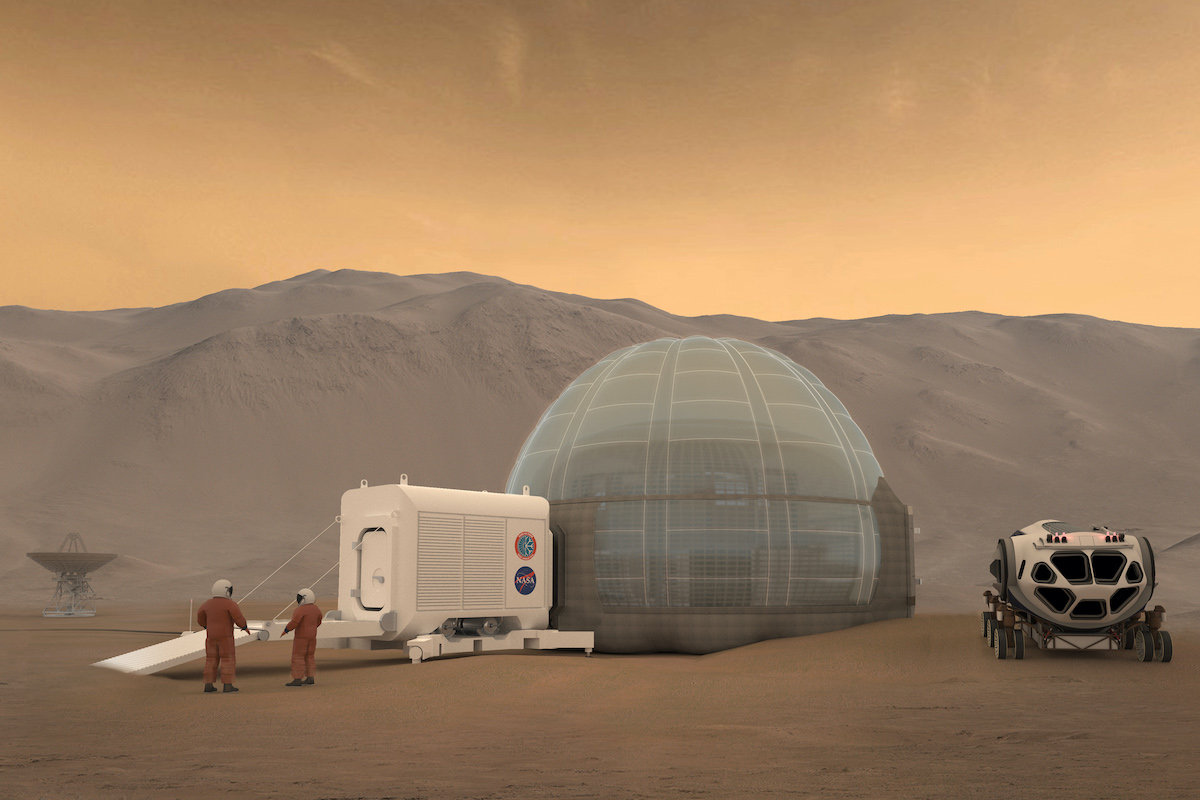

On the flip side, Mars has no magnetic field, which means that explorers and colonists would have to deal with high levels of dangerous solar radiation and cosmic rays, on top of the more obvious challenges associated with access to oxygen, heat and food. But none of these obstacles are insurmountable. Nor should we be discouraged by concerns that humans on Mars might return to Earth with deadly pathogens that wipe out terrestrial civilization, as set out by Quillette contributor Armondo Simón in his Dec. 28 contribution to this series.

“Far better to use that [space-exploration] money to set up a permanent base on the moon, from which we could keep a sharp lookout for near-Earth asteroids,” Simón concluded. “Instead of inviting human extinction on other planets, let’s try to keep humanity alive on the one we’ve already got.” But Simón’s fears are overblown.

Mars did once feature conditions that were amicable to carbon-based lifeforms such as are found in every environment on Earth. And it is conceivable that somewhere on that desert planet, life still holds on—perhaps in some underground geothermal pool, fed by remnants of the once mighty heat flows associated with the (now dormant) Martian volcanoes. If such life is still present, humans will likely find it. In fact, that was one of the primary reasons we sent robots to the planet—and the search will doubtless continue when we go there ourselves. But when we do find Martian life, it will be harmless to us.

How do we know this? Because if life on Mars exists, we’ve likely already been exposed to it. Each year, the Earth gets hit by countless small objects from space, as well as a few larger ones. The majority of these come from farther out in the solar system. But at least some of them began their journey on Mars. Larger impacts on rocky planets such as Earth and Mars can blast chunks of material off the surface and into space. Eventually, a small number of these arrive on other planets in the inner solar system. A well-known example is the Martian meteorite ALH84001, a fragment of which was found in Antarctica in 1984.

Robert Zubrin, founder of the Mars Society, notes in his excellent 2019 book The Case for Space that studies of “meteorite ALH84001 have shown that portions of it never rose above 40C at any time during its entire interplanetary journey, and therefore, if there had been bacteria within it when it departed Mars, they easily would have survived the trip.” He also notes that Earth probably receives about half a metric ton of Martian meteorites each year. So, if there’s any life still existing on Mars, don’t worry about it: Your ancestors were exposed to it long ago.

Even the idea that organisms from other planets could suddenly infect us is far-fetched. Our bodies are hostile venues for microorganisms. And those that do succeed in infecting us are specially adapted to our physiology. Yes, we can catch diseases from a few other animals, usually other mammals (an example being coronaviruses, such as the strain that recently has been spreading, to deadly effect, out of the Chinese city of Wuhan). But once the biological differences become large, transmission becomes impossible. Humans cannot catch leaf rust from wheat, nor can worms catch a cold from humans.

Even if a completely new (to us) Martian microorganism got back to Earth and into our environment, there is no chance that it would take over the terrestrial biosphere. It simply would not be adapted to thrive here. Zubrin compares “the notion of Martian organisms outcompeting terrestrial species on their home ground (or terrestrial species overwhelming Martian microbes on Mars)” to the idea that “sharks transported to the plains of Africa would replace lions as the local ecosystem’s leading predator.”

Fears of Martian life killing us represent an interplanetary extrapolation of a more general attitude called the precautionary principle, which originally was embedded in the 1992 Rio Declaration on Development and Environment: “In order to protect the environment, the precautionary approach shall be widely applied by States according to their capabilities. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.” While this language would seem to channel a common-sense approach, the precautionary principle has been applied to quash beneficial scientific pursuits from nuclear power to GMOs. Technically, any unknown “serious” danger can be leveraged to slow projects to a crawl or halt them altogether.

Large, visionary projects, such as a human mission to Mars would surely be, are particularly vulnerable to being quashed under the Precautionary Principle—because, where such projects are concerned, there are no limits to conceivable threats other than the boundaries of human imagination. And so this principle can become an all-purpose excuse for timidity. When humans do start building humanity’s Martian branch office, the type of men and women who lead that society will not be the sort to worry about far-fetched what-ifs. They will be tough-minded, practical individuals who teach themselves how to survive in a harsh new world.

If anything, we should be fearful that human colonists on Mars may destroy Martian life, not vice versa. For the reasons described above, the prospects of Earthly microbes outcompeting their Martian counterparts on their home turf is unlikely. But as we start to terraform Mars, we may wipe out any native microbes due to the extensive changes inflicted on the Martian environment. Though Mars was once wet and at least reasonably warm, it is probable that any surviving microbial species are super-specialized extremophiles. While reservoirs of hot fluids underground or other niche environments may continue to provide a refuge for these microbes in the face of increasingly Earth-like conditions, even such remote habitats may well become inhospitable (to them) in the long run.

Do we have the right to supplant Martian life with our own? Yes—because a human life has more value than that of a bacterium. Since we will not be encountering any sentient life forms on Mars, we do not have to worry about replicating the evils associated with colonization back on our own planet.

While future Martians will no doubt study and preserve samples of any life they come across on the red planet, their main goal will be to turn Mars from a dead (or mostly dead) world into a lush and self-sustaining human habitat. It would be a proud accomplishment, and perhaps one on which our survival as a species depends. So as we seize this Martian moment, let us not burden ourselves with false fears.