Education

How Most American Kids Are Kept Out of the Best Public Schools

Abolishing attendance zones will not make the problems of our education system disappear overnight.

Nothing about North Avenue in the Old Town neighborhood of Chicago feels like a political barrier or a sociological fault line. Residents of Old Town cross busy North Avenue every day. If you live north of North, you might cross the street to meet a friend for a pint at the Old Town Ale House. If you live to the south, you might cross North Avenue to see a show at the world-famous Second City comedy club or to take your family to the 11am choir service at St. Michael’s Catholic Church. If you need medical care in Old Town, no matter which side of North Avenue you live on, you have your choice of Family Urgent Care on the north or Physicians Immediate Care on the south. Both receive excellent ratings from patients.

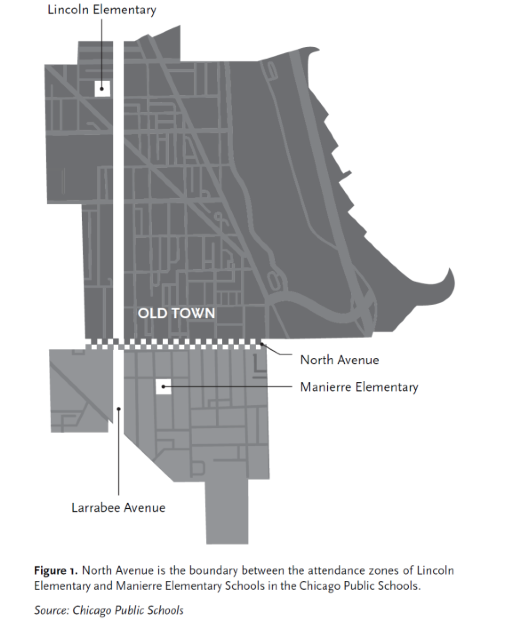

But North Avenue is a fault line in one extremely important way. If you stand at the corner of Larrabee and North, there are two public elementary schools within a mile. Both schools are operated by Chicago Public Schools (CPS). Both are governed by the decisions of the Board of Education. Both are funded by Chicago residents, who pay property taxes directly into the CPS General Fund. So residents living north and south of North Avenue share the burden of funding the two schools. However, neighborhood families do not share equal access to the two local schools. The district has split the community into two groups: If you live north, you go to Lincoln Elementary. If you live south, then you’re assigned to Manierre Elementary.

Let’s look at the two schools. Turn north on Larrabee Street and walk seven blocks to Lincoln Elementary, one of the crown jewels of Chicago Public Schools. Lincoln gets a “1+” rating from the district, the highest possible rating. And the school encompasses the prestigious French-American School of Chicago, officially recognized by the French Ministry of Education and open only to students of Lincoln Elementary. Start once again at Larrabee and North. Turn south this time, and walk five blocks to Manierre Elementary, which receives a “3” rating from the district, the lowest possible rating. Manierre doesn’t just lag Lincoln. Manierre, by any objective standard, is a failing school.

Compare the reading proficiency of students at the two schools: At the end of the 2018–19 school year, not a single eighth grader from Manierre was proficient in reading, compared to 81 percent of Lincoln eighth graders. Take a moment to let those numbers sink in. The difference between the two schools is staggering. These two schools serve the same neighborhood and are a mere 1.3 miles apart. If these were health clinics or restaurants, there’s no chance that such stark differences would persist in establishments within walking distance of one another. Randall Blakey is the pastor of LaSalle Street Church just a few blocks south of Manierre. “If the Manierre parents had the same choices as every other parent north of North Avenue,” he says, “I’m sure they’d take advantage of the choices.”

But the children south of North Avenue aren’t allowed to attend Lincoln. “We fell in love with a townhome in Old Town,” says Angela Mota, the parent of a four-year-old who will enroll in elementary school next year. She and her husband found out too late that their home is on the wrong side of the line. “I thought Old Town had good schools,” Angela remembers. “And then we got here, and it’s like ‘Oh, crap.’” The Motas are now looking into magnet schools and other selective public schools that might allow them to escape Manierre without having to pay tens of thousands in private school tuition. Lincoln, just a few blocks from their house, isn’t an option.

Brian Speck lives just a few blocks north of the Motas and is the father of two boys who have attended Lincoln. “There’s a barrier to entry to Lincoln Elementary,” he says, “And that’s both good and bad.” Brian says that he and his wife had their eye on one home that was south of North Avenue and $250,000 cheaper than the house they bought. “But private school in Chicago can run up to $40,000 a year,” he laments. So they paid the extra $250,000 so that their kids could attend a “free” public school. Children growing up in Old Town are sorted and separated when they enroll in kindergarten—when they are just five years old.

Is Lincoln Elementary a public school?

In 2013, the schools in the neighborhood were at a tipping point. Lincoln was 129 percent overcrowded, partially due to young families moving into the school boundaries in order to gain access to the elite public school. Many families assigned to Manierre, black and white, would seek out private schools or find another public option, such as a charter or a magnet school. This left Manierre with plenty of empty classrooms.

The logical solution in Old Town would have been to redraw the attendance boundaries so that some of the Lincoln families would have been redirected to Manierre or another local school with space. But that’s not what happened. Instead, top district officials proposed to close Manierre down and invest $19 million in a renovation of Lincoln that would increase the school’s capacity. Would the additional space allow any of Manierre’s children to transfer to Lincoln and finally escape their failing school? No, the addition would simply allow Lincoln to serve students in the existing attendance zone, but more comfortably.

Manierre’s students would have been reassigned to Jenner Elementary, another failing school with excess capacity. A huge political fight followed. The Chicago Teachers Union filed a lawsuit to block the closure. The lawsuit was dismissed, but eventually Manierre was allowed to stay open, partially because the Manierre students would have had to cross gang lines in order to get to Jenner, possibly putting them in physical danger. Now Lincoln has a larger, updated building that is at 94 percent capacity. According to Chicago Public Schools, the newly renovated building at Lincoln has a capacity of 1,080 students, but only 956 were enrolled in 2018. That means there were 124 open seats at the school. Yet Lincoln still refuses to admit any students who live south of North Avenue.

You can’t talk about Lincoln and Manierre without talking about race. Many Manierre kids come from the Marshall Field Garden Apartments, a subsidized housing development just south of North Avenue. Manierre’s kids are 96 percent black and four percent Hispanic—and 93 percent low income. Lincoln is 63 percent white, and only 14 percent of the students are low income. But race is not what’s keeping kids out of Lincoln Elementary. What keeps Old Town kids out of Lincoln Elementary is geography—the artificial boundary of North Avenue.

The neighborhood’s black alderman Walter Burnett told the Chicago Tribune back in 2013 that middle-class black residents of Old Town will not send their kids to Manierre. “If you’re a middle-class parent in the Manierre zone,” confirms Pastor Blakey, “you end up paying for private education, or you work your political connections to get your kid into a Selective Enrollment school.” The original idea of a public school—championed by Horace Mann and the Common School Movement of the 19th century—is that it’s a place where everyone in a community can send their kids, a place where all the races and classes mix, and a place where less privileged kids have the same chances as anyone else. But that’s not what Lincoln Elementary is.

If only this were a problem unique to Chicago! We’ve identified many similar school pairs in cities across the U.S.—one elite public school and one failing public school, separated by nothing more than an arbitrary line drawn by a school district bureaucrat. Take a look at PS 8 and PS 307 in Brooklyn. Ivanhoe Elementary and Atwater Avenue Elementary in Los Angeles. Mary Lin and Hope-Hill in Atlanta. John Hay and Lowell Elementary Schools in Seattle. Lakewood and Mount Auburn in Dallas. Clinton and Como Elementary Schools in Columbus. Cory and Ellis Elementary Schools in Denver. Penn Alexander and Henry Lea in Philadelphia. This is an American phenomenon.

Educational redlining

I recently called Lincoln Elementary and pretended to be a parent moving to Chicago. I asked the staff member who answered the phone how we could get our children into Lincoln. “It is a neighborhood school,” she told me. “It’s an attendance area. So if you want your child to go here, you have to move within the boundaries.” And if we get a house within the boundaries? “You’re automatically in. You just have to show proof.”

This moment—when a school staffer asks for proof of your address—is one that happens thousands of times every year in America. This is precisely the moment I want to examine closely.

- Imagine you show up at a nearby emergency room with a broken arm, and the nurse at the front desk asks for proof of your address before taking you in for an X-ray.

- Imagine you walk into the neighborhood branch of your city’s library. You sit down at a computer, and a librarian comes over to check your ID. “Sorry,” she says. “I know you live in the city, but you’re assigned to a library two miles away. You’ll have to leave.”

- Imagine that there’s a fire in the neighborhood, and the Station 22 fire truck won’t water down your home because the truck’s onboard computer shows that you’re just over the line, zoned for Station 44.

The staff member at Lincoln Elementary isn’t simply trying to ensure that you live within Chicago Public Schools’ jurisdictional boundaries. That would make some sense, because you might not want nonresidents coming in and getting a free education at schools that were paid for by resident taxpayers. No, this employee at Lincoln Elementary is interested in whether you live on the right side of an attendance-zone boundary, which is a line drawn around the school by the district staff. The key questions are: Why do the staff at the school ask for proof? What empowers them to turn away students who don’t live in the attendance zone? The short answer is—state law.

This is the great secret of public education in the U.S. In most states, there are little-known state laws that require or allow school staff to ask this question and make enrollment determinations based on where a family lives within the district. In other states, there are simply no laws that prevent school officials from drawing attendance-zone boundaries. It is implicitly allowed. In Pennsylvania, for example, a law from the 1940s explicitly requires that each district carve itself up into attendance zones. In California, the requirement is—ironically—tucked into the “open enrollment” law, which allows students to attend any school within their district of residence, as long as “no pupil who currently resides in the attendance area of a school shall be displaced.” That banal phrase allows—even requires—California school districts to reserve the best schools for the privileged few who can afford to live within the boundaries.

Note again that I’m not talking about the boundaries between school districts, which are political subdivisions. Those lines are jurisdictional. As governmental entities, school districts are typically overseen by elected or appointed board members. School districts often have the legal authority to assess taxes on their constituents or issue bonds in order to fund the district’s activities.

Attendance zones, on the other hand, are administrative service areas. Government bureaucrats carve up the map and determine who gets preferred enrollment at what school. There are no elected officials at the attendance-zone level—and no political representation. The residents of a school zone are not subject to special taxes that go to the local school. Over the past several years, I’ve been digging up these obscure laws to understand how and why our schools remain separate and unequal. I’ve also been collecting the stories of parents—of all races and income levels—whose lives have been twisted into knots by these bizarre policies.

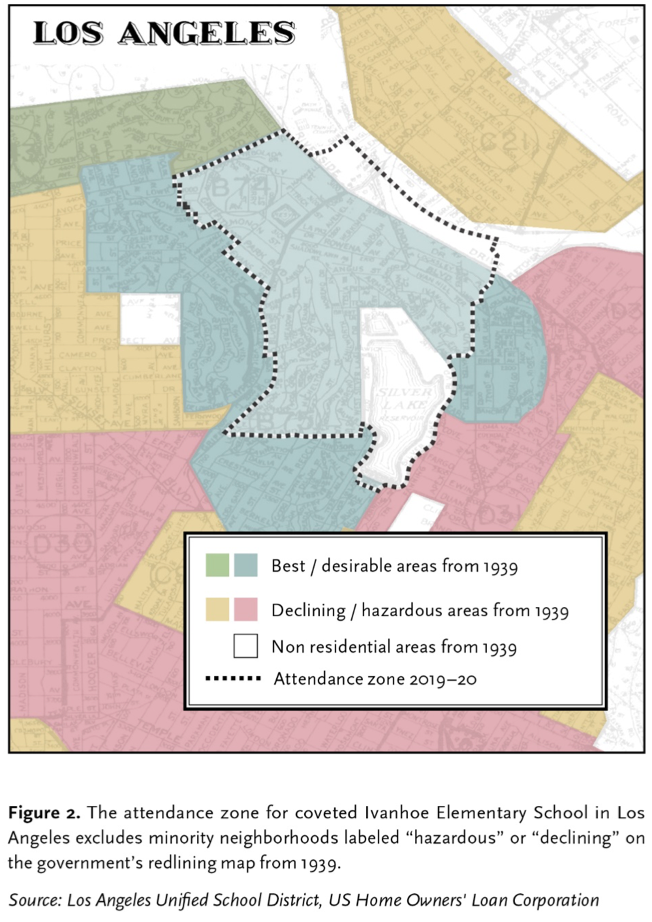

We already have a name for this practice of using your address to determine whether or not you are eligible for valuable government services. We call it redlining. The name comes from government maps created during the New Deal. These maps used the color red to indicate those urban neighborhoods that were “hazardous,” which mostly meant that those areas were majority black or Hispanic. People in these red-shaded portions of the map were ineligible to qualify for some federally subsidized mortgages and housing assistance.

Educational redlining is analogous to redlining in the housing market. In each case, valuable government services are reserved for more privileged communities, using geographic preferences as a way to limit who is eligible to receive them. Redlining in the real estate market was made illegal by Congress with the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 and the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977. Government agencies and private banks are now forbidden from using these tactics that reinforced racial divisions and inequality.

But when we carve up our cities into attendance zones, we perpetuate the economic and racial divisions that marked one of the darkest eras of our nation’s past. In many neighborhoods, you can still see the ghost of the redlining map when you look at a current map of the local school’s attendance zone. Figure 2 shows the current attendance zone of Ivanhoe Elementary School in Los Angeles superimposed on the redlining map of the Silver Lake neighborhood from 1939. Ivanhoe Elementary is one of the most coveted public schools in Los Angeles. Note how the minority neighborhoods of Silver Lake remain on the outside looking in.

Eighty years after the creation of the map, the schools that serve the red and yellow areas of the map are still all majority Hispanic, while Ivanhoe is 75 percent white. This same pattern holds true for the attendance zones of other elite public schools around the country—PS 8 in Brooklyn, Lakewood Elementary in Dallas, Mount Washington Elementary in Los Angeles, and the school called Center for Inquiry 84 in Indianapolis. In Chicago, it’s different. The “desirable” areas on the North Side have changed, so the attendance zone of Lincoln Elementary no longer reflects the geographic divisions of 80 years ago. But somehow areas with significant minority populations still find themselves on the wrong side of the line.

In 1951, Linda Brown’s race was used to keep her out of Sumner Elementary School. In 2020, a line drawn down the middle of North Avenue is used to keep Old Town kids out of Lincoln Elementary.

School choice and segregation

There’s a whole genre of education writing based on the idea that “school choice” is the reason that our schools are racially segregated and unequal. Take, for instance, an article by Allison McCann in VICE News entitled “When School Choice Means Choosing Segregation”:

The resegregation of America’s public schools is due largely to two decades of Supreme Court rulings that all but ended mandatory desegregation plans, but it has not been helped by the growing movement toward school choice.

Or take the opinion piece “School Choice Is the Enemy of Justice” by Erin Aubry Kaplan in the New York Times:

Black and brown students have more or less resegregated within charters, the very institutions that promised to equalize education.

Or look at the academic white paper produced by the UCLA Civil Rights Project, “Choice without Equity: Charter School Segregation and the Need for Civil Rights Standards”:

As the country moves steadily toward greater segregation and inequality of education for students of color in schools with lower achievement and graduation rates, the rapid growth of charter schools has been expanding a sector that is even more segregated than the public schools.

Sounds damning, doesn’t it? But these scholars and journalists choose to ignore the fact that almost 80 percent of public school children attend their assigned public school. If American public schools are divided along economic and racial lines (and it’s indisputable that they are), then it is primarily because of geographic school assignment, not because a minority of parents look to escape the failing schools they’ve been assigned to.

Perhaps fewer minority families would choose charter schools if they had equal access to the best public schools in their communities. If you want to break down the racial and social divisions in our schools, that’s the first place to look.

Opening up the schools

Recently I dialed up John Hay Elementary in the hilly Queen Anne neighborhood of Seattle. This is a school that bears a strong resemblance to Lincoln in Chicago or Ivanhoe in Los Angeles. To enroll your kids at John Hay, a staff member tells me, “You want to be on the north side of Denny Way.” Otherwise your kids will be zoned to go to struggling Lowell Elementary. “It is unfair,” she says, “but you have to have boundaries somewhere. Otherwise no one would want to go to that school [Lowell].”

I take her point about the lack of parent demand for failing schools like Lowell. But she’s wrong about the need for attendance zones. There are other ways to do it. Public charter schools, for example, hold open lotteries when applications exceed the number of open seats. In most states, charter schools are forbidden from discriminating against families based on where they live within the school district. The open-to-all policy for charters is the result of political battles led by teachers’ unions and school boards to make it illegal for charters to cherry-pick the students they enroll. (Some charters still try.) Indeed, there are several states, my home state of California included, in which traditional public schools are required by law to discriminate based on residential address, and public charter schools are explicitly forbidden from doing exactly that.

I’ve come to believe that public education would simply work better if our laws forbade districts from drawing these lines, rather than allowing them or even requiring them to do so. Imagine a world in which every public school was open to applications from any family in the district and was required to hold a lottery to determine who would be admitted. In such a world, parents wouldn’t have to play the games they play today, making gut-wrenching decisions about real estate and housing in order to do what’s right for their children.

Critics will argue that a fully open system would be unworkable. How would a district plan from year to year, if any student could go to any school? But there are ways to make it workable. Tony Miller, former Deputy Secretary of Education under President Obama, suggests that a school district could provide transportation to any school within a three-mile radius of a student’s home. Other district schools would be open to that student, but her family would have to arrange for transportation—perhaps partially subsidized by the district—for those more distant schools.

On a personal level, we should all have sympathy for the people who would oppose such reforms. Take a family who has paid $250,000 more for a house because of its guaranteed access to an elite public school. Those parents wanted to secure the best education for their children, and that’s always laudable. But that doesn’t mean we should continue to block open access to these public schools.

In many ways, these people are like the taxi companies in New York City. Taxi companies paid millions of dollars for “medallions” allowing them to operate taxis within the city. For years, these medallion owners fought off efforts to issue more medallions—and improve taxi service for millions of New Yorkers—because they wanted to be protected from the competition. With the emergence of ride-sharing services such as Uber, the medallions have become almost worthless. And taxi companies have attempted to use their political clout to block such services and retain their protected position.

But the courts have said no. Buying a taxi medallion does not mean that you are protected from disruptive competition until the end of time. Likewise, buying a house that gives you preferential access to a public school does not mean that you will be able to keep other families out forever.

Of course, proximity matters! I have young children, and one of our biggest priorities is finding a school—near our home—that will meet our kids’ social, emotional, and intellectual needs. A school is often a place where a community coheres, and it’s reasonable to fear that the social cohesion—and the cachet—of a school like Lincoln Elementary would be diluted if it were open to a broader segment of the public.

But social cohesion and cachet shouldn’t be built on a foundation of discriminatory policies that exclude other local families. When the state legislature creates school district boundaries, it indicates that everyone within those lines will share a set of public schools. Within those lines, it’s wrong to exclude children based on where they live—just as it was wrong to exclude them based on their race.

In a world of truly open public schools, families will sort themselves based on what they think is most important, and the vast majority of families will select schools near their homes. They won’t need the government to draw lines around the schools that keep other people out. It will happen organically.

As it happens, my family lives just outside the attendance zone for another elite school in Los Angeles, Mount Washington Elementary. My own kids and many of our neighbors’ kids, of all ethnicities, are excluded from the school even though it is the closest school to our house. The district map assigns our family to a struggling school only marginally better than Manierre Elementary in Chicago.

For our family, this isn’t a huge concern. We have the resources to send our kids to private school, if necessary, and we also have the savvy to navigate the byzantine system of school choice in Los Angeles. We will likely be able to find a school that is a good fit for our kids and that performs better than their assigned school. But for families with lesser means this geographical exclusion is a much bigger issue, one with life-altering consequences.

Abolishing attendance zones will not make the problems of our education system disappear overnight. There are no panaceas for the ills of our schools. No easy fixes. And segregation and inequality are likely to persist in some form. Decades of separation, complacency, and bad policy cannot be overcome with any single reform.

But middle-class and lower-income families deserve an equal opportunity to enroll their kids in the best public schools.