Books

The National Book Foundation Defines Diversity Down

Last month the Huffington Post published an essay by Claire Fallon entitled “Was this Decade the Beginning of the End of the Great White Male Writer?” Fallon celebrated the notion that white men are losing their prominence in contemporary American literature and that the best books being published in America today are being written by a wider variety of authors than ever before:

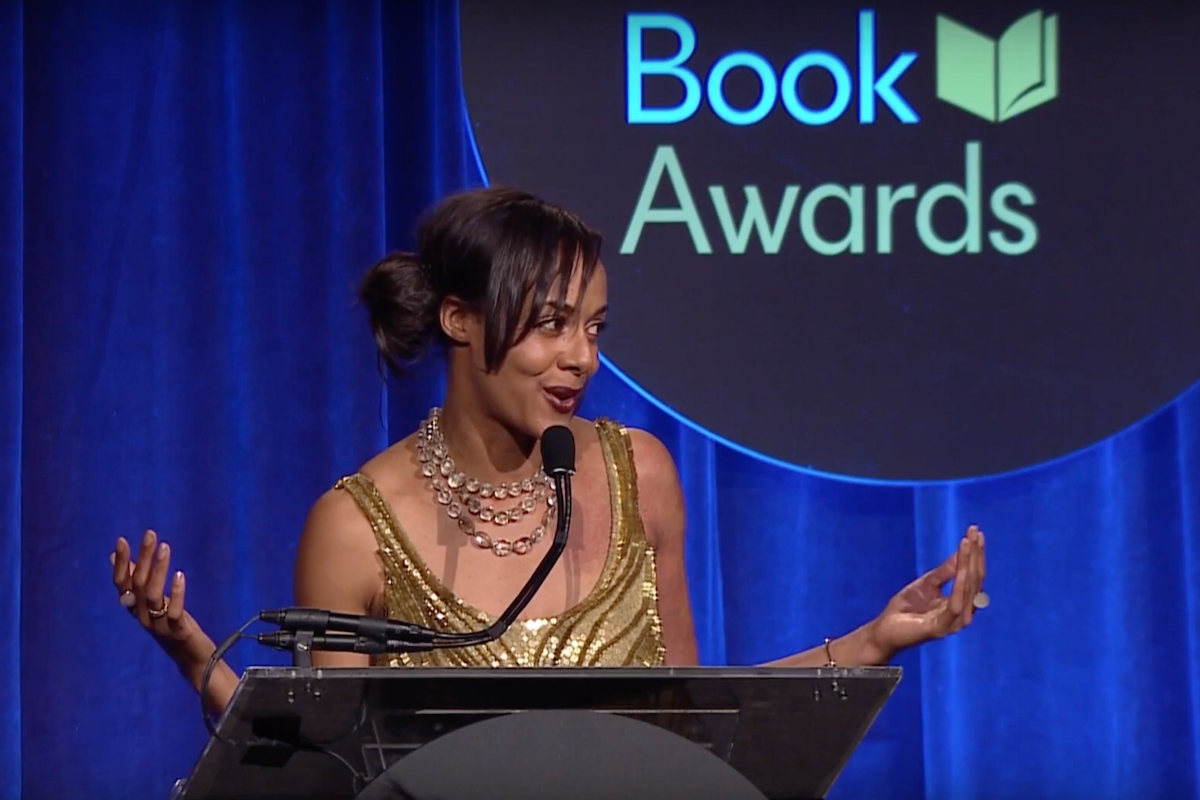

“What was once insular is now unifying,” National Book Foundation director Lisa Lucas told the crowd at the 2019 National Book Awards Gala, where the fiction, nonfiction, and poetry honors all went to writers of color. “What was once exclusive is now inclusive.”

Lucas took over the foundation in 2016, at a time when the high-profile awards had a somewhat checkered record with representation. Though historically the honorees had skewed heavily white and male, that began to change around 2010. (However, there had been some other recent embarrassments, like 2014 host Daniel Handler’s racist jokes following author Jacqueline Woodson’s win for “Brown Girl Dreaming.”) Lucas, the first woman and person of color to helm the foundation, made representation and inclusivity a focus of her messaging. When looking back at the past decade, she told HuffPost in an interview, a multipronged effort to build a more inclusive literary scene has indeed paid dividends.

Of the past 10 National Book Awards for fiction, six have gone to women and seven to writers of color, including two wins for novelist Jesmyn Ward.

Lucas pointed to the presence of more people of color and women in influential positions—on university faculties, in powerful roles in publishing, on awards committees, writing for media outlets—as a force in expanding who is encouraged and recognized.

Lucas also argued that readers have been hungry for books reflecting the multiplicity of human experience and have rewarded publishers for devoting more resources to them.

But is Lucas correct? Are contemporary National Book Award (NBA) winners and nominees a more diverse lot than those of previous eras? Actually, no, not unless your only criterion for diversity is skin color or ethnicity. By any other measure, the authors honored by the National Book Foundation over the past decade are a surprisingly homogenous group. Almost all of them are products of what has come to be known, among supporters and critics alike, as America’s “MFA Industrial Complex.” They all tend to matriculate at the same elite colleges, acquire advanced degrees in English or Creative Writing, and then go on to teach in the same circle of elite schools.

In 2010, the National Book Award for Fiction went to Jaimy Gordon, who has a doctorate in Creative Writing from Brown University and has taught in the MFA program at Western Michigan University. She beat Lionel Shriver, who has an MFA from Columbia, Nicole Krauss, who has degrees from Stanford and Oxford, Karen Tei Yamashita, a professor of literature at U.C. Santa Cruz, and Peter Carey, a member of the MFA faculty at Hunter College in New York.

In 2011, the NBA for Fiction was awarded to Jesmyn Ward, an English professor at Tulane (she would win it again in 2017). She was once a Stegner Fellow at Stanford and taught Creative Writing at the University of the South. She beat Tea Obreht, who has an MFA from Cornell and teaches in the same MFA program as the aforementioned Peter Carey. Another finalist that year was Julie Otsuka, who has an MFA from Columbia and an undergraduate degree from Yale. Both Obreht and Otsuka grew up in Palo Alto, home of Stanford University and the Stegner Writing Program.

In 2012, the NBA for Fiction went to Louise Erdrich, who earned an MA in Writing from Johns Hopkins University. She has been writer-in-residence at Dartmouth. She beat Junot Diaz, who has an MFA from Cornell and teaches Creative Writing at MIT, and Kevin Powers, who has an MFA from the University of Texas.

In 2013, the winner was James McBride, an Oberlin graduate who is a writer-in-residence at NYU. He beat Rachel Kushner, who (like the aforementioned Lionel Shriver and Julie Otsuka) has an MFA from Columbia. He also beat Jhumpa Lahiri, who has an MFA from Boston University and is a professor of Creative Writing at Princeton, and George Saunders, who has an MA in Creative Writing from Syracuse.

The 2014 winner was Phil Klay, who has an MFA from Hunter College (where the aforementioned Peter Carey and Tea Obreht teach). He beat Anthony Doerr, who has an MFA from Bowling Green, and Marilynne Robinson, who once ran the Iowa Writers Workshop.

The 2015 NBA for Fiction went to Adam Johnson, who has an MFA from McNeese State University and teaches Creative Writing at Stanford. He beat Lauren Groff, who has an MFA from the University of Wisconsin, Karen Bender, who has taught in various MFA programs, and Angela Flourney, an Iowa Writers Workshop alum who also has taught in various writing programs.

In 2016, the prize went to Harvard graduate Colson Whitehead, who beat Karan Mahajan, who earned an MFA at the University of Texas (where Kevin Powers got his MFA).

The judges of the National Book Award are generally drawn from the same group of academics as the recipients of the prize. For instance, Jesmyn Ward and Julie Otsuka were judges in 2016, when Whitehead got the Award. Adam Johnson was a judge in 2014, the year that Phil Klay won.

Although they may come from diverse ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds, from about the age of 22 onwards, today’s NBA honorees have almost identical professional arcs: grad school, the awarding of an MFA, a job at an elite university and a dual career as an author of mostly mid-list novels.

It wasn’t always thus. Prior to the 1980s, the list of winners and runners up generally included plenty of writers with no college at all. James Jones’s formal education ended at 17, when he left high school to enlist in the U.S. Army. His novel From Here to Eternity won the NBA in 1952. One of the runners up that year was Truman Capote’s book The Grass Harp. Like Jones, Capote never attended college. His formal education ended at 18, when he graduated from prep school. Also nominated for an NBA in 1952 was William Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun. Faulkner dropped out of the University of Mississippi after three semesters. He earned a D in English.

Among the authors recognized by the National Book Foundation in 1953 were Ernest Hemingway, who had no college, and John Steinbeck, who spent a few years at Stanford but never graduated. In 1955, the NBA in fiction was won by Faulkner’s A Fable. Among the runners up were Steinbeck again and William March, author of The Bad Seed. According to Wikipedia: “March grew up in rural Alabama in a family so poor that he could not finish high school, and he did not earn a high school equivalency until he was 20. He later studied law but was again unable to afford to finish his studies.”

J.F. Powers, who was a nominee in 1957 and a winner in 1963, took classes in Chicago at both Wright Junior College and Northwestern University but never earned a degree. J.P. Donleavy, a nominee in 1959, took classes at Trinity College, Dublin, but never graduated. Harper Lee, a nominee in 1961, took some law classes at the University of Alabama but never earned a degree.

In later years, the honorees would include Isaac Bashevis Singer, who had no college degrees other than honorary ones, John Cheever, who had no college education, Katherine Anne Porter, whose formal education ended after one year of high school, and John O’Hara, who never attended college (and burned with resentment because of it for the rest of his life). You’d be hard-pressed to name a more distinguished quartet of American short story writers than Singer, Cheever, Porter, and O’Hara. Certainly you won’t find one among the recent recipients of the NBA. O’Hara won an NBA in 1956 for his novel Ten North Frederick. One of the runners up that year was MacKinlay Kantor’s Civil War novel Andersonville, which won the Pulitzer Prize. Kantor had no college education either.

But even those earlier recipients of recognition from the NBA who did have a college education represented a much wider spectrum of academia than the current lot do. West Virgina’s Bethany College, Kentucky’s Berea College, Whittier College in Southern California, the University of Colorado at Boulder, the University of Montana, Belhaven College of Jackson, Mississippi, Lake Erie College of Painesville, Ohio—graduates of these and other lesser known schools all received recognition from the National Book Foundation in the mid-twentieth century.

And it wasn’t just educational diversity that distinguished the NBA winners of earlier decades. They were also a fairly diverse lot politically. The honorees included opponents of the Vietnam War, such as Mary McCarthy, Nelson Algren, and John Hersey, and supporters of the war, such as John Updike, John Steinbeck, and Vladimir Nabokov. They included rock-ribbed Republicans such as James Gould Cousins and Louis Auchincloss, as well as Democratic office-holders such as Robert Traver (real name: John D. Voelker), who in 1934 was the first Democrat elected Prosecuting Attorney in Marquette County, Michigan, since the Civil War and would later serve on the state’s Supreme Court. Ayn Rand, the spiritual godmother of contemporary American conservatives such as Clarence Thomas, Paul Ryan, Ron Paul, and Rand Paul (who, contrary to legend, is not named after her) was a nominee, for Atlas Shrugged, in 1958.

Saul Bellow, the only writer to win a National Book Award for Fiction three times and a recipient of the National Book Foundation’s Lifetime Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters in 1990, was well known for his conservative cultural activism. According to Wikipedia:

His opponents included feminism, campus activism and postmodernism. Bellow also thrust himself into the often contentious realm of Jewish and African-American relations. Bellow was critical of multiculturalism and according to Alfred Kazin once said: “Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus? The Proust of the Papuans? I’d be glad to read him.”

Try to imagine an author with attitudes like those winning a contemporary NBA. Judging from their books, their occasional newspaper commentaries, and their Twitter feeds, today’s NBA winners are a politically homogenous lot. You won’t find any of them criticizing feminism or multiculturalism.

One of the most important American books of the decade just ended was J.D. Vance’s memoir Hillbilly Elegy, which tells how his impoverished Appalachian boyhood made a conservative of him. The book was a widely praised bestseller but was snubbed by both the NBAs and the Pulitzer Prize committee. Thomas Mallon is one of America’s greatest living historical novelists, having penned fictional forays into the Nixon White House, the Reagan White House, and the George W. Bush White House. Despite having attended all the right schools (Brown, Harvard) and being in a committed same-sex relationship, Mallon nonetheless gets little love from the NBA and Pulitzer crowd, no doubt because he is a conservative Republican.

It isn’t a bad thing if MFA holders publish novels and win prizes for them. But it is a problem when only MFA holders are publishing novels and winning prizes for them. Not too long ago, novel-writing was a trade practiced by a wide variety of Americans. Nowadays it is rapidly becoming just another profession requiring certification by a priesthood of insiders. According to a report by the National Conference of State Legislatures, the number of American jobs requiring state certification has risen from one in 26 years ago to one in four today.

No, novelists are not technically required to be board- or college-certified in order to practice their trade in America. At least not yet. But the weed-like growth of the MFA Industrial Complex is creating a sort of de facto certification process. I know any number of talented writers who, lacking an MFA or even a college degree, can’t get their books published because no one in the publishing world wants to look at work from outside the usual channels. If you’re wondering why you see so few Truman Capotes and James Joneses and John Cheevers these days, one-off literary geniuses whose work doesn’t seem to resemble any particular school of literature but their own, the answer is the American MFA Industrial Complex and its stranglehold on the publishing world.

And it isn’t just conservative writers or autodidact writers who are passed over by the NBAs. Plenty of authors who would seem to fit comfortably into the National Book Foundation’s idea of what a serious writer should look like (female, elite education, etc.) appear to be locked out simply because they do not hold MFAs or teach creative writing. Consider, for instance, Gillian Flynn, author of Gone Girl and other bestsellers. She has a master’s from Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism. Gone Girl was one of the most talked about novels of the decade just ended. It touched on a lot of topical issues: spousal abuse, media sensationalism, the different ways that men and women view issues of sex, love, and marriage, and so on. In decades past, the NBA frequently honored titles that appealed both to lovers of serious literature and lovers of pop fiction: From Here to Eternity, The Caine Mutiny, Anatomy of a Murder, The Man With the Golden Arm, The Bad Seed, The Catcher in the Rye, Marjorie Morningstar—the list goes on and on. Gone Girl would seem to fit perfectly into that category of intelligent bestseller.

But Gillian Flynn isn’t a tenured professor in the MFA Industrial Complex, and thus her work appears to not even have been considered for a National Book Award. The same thing is true of Delia Owens’s current bestseller Where the Crawdads Sing. The novel deals with sexual assault, child abuse, female empowerment, and other issues that ought to speak to the gatekeepers of the National Book Awards. Owens is highly educated but her degrees are in Zoology and Animal Behavior. She doesn’t teach creative writing at an elite university. As a result, her book, which has drawn praise from both serious literary readers and fans of pop fiction, has been snubbed by those who grant Pulitzers and NBAs.

If National Book Foundation director Lisa Lucas wants to see what real literary diversity looks like, all she has to do is delve into her own organization’s archives. Sure, most of those earlier honorees were white and male, but in many ways they represented a far more diverse group of Americans than today’s NBA honorees do. What’s more, many of their books became permanent cultural landmarks. Gone With the Wind by Margaret Mitchell (who dropped out of college after one undistinguished year) remains one of the bestselling and most loved American books of all time. It won a National Book Award in 1936. Many another old NBA winner or runner up has become a cultural landmark as well: From Here to Eternity, Invisible Man, The Adventures of Augie March, The Catcher in the Rye, The Caine Mutiny, The Old Man and the Sea, East of Eden, Giovanni’s Room, Atlas Shrugged, The Ginger Man, Lolita, The Haunting of Hill House, Goodbye Columbus.

Over the past decade, the National Book Foundation has honored works of fiction such as Great House, I Hotel, So Much For That, Binocular Vision, Refund, The Throwback Special, The Association of Small Bombs, and a lot of other books whose authors not one in 10,000 Americans can probably identify. Decades from now, when people look back on the Lisa Lucas era at the National Book Foundation, they may see a whole lot of ethnic diversity and not much more—except for a lot of forgotten and out-of-print titles.