Cinema

'White Christmas' and the Triumphs of the Greatest Generation

Viewed as a romantic comedy, a bromance, or a musical, White Christmas may seem like just a lightweight piece of Hollywood fluff. But considered as a hymn to post-war America, it acquires additional depth.

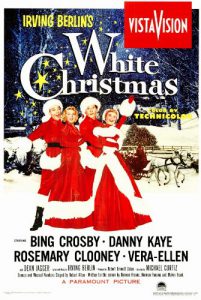

Michael Curtiz’s 1954 classic White Christmas is so popular that it generates new think-pieces every time the holiday season rolls around. Last year, the New York Times republished its own original review of the film, in which the late Bosley Crowther panned the movie. Other pieces in other places discussed Vera-Ellen’s alleged bulimia, the fact that her neck is covered throughout the film, the rumor that Bob Fosse was an uncredited choreographer on the film, and the many continuity errors. The film has been called a romantic comedy, a buddy picture (or “bromance”), a musical, and a holiday film. Curiously, I’ve never seen it listed in the war genre, which is the category in which it really belongs.

For all its holly and ivy and hot-buttered rum, White Christmas is as much about World War II as Edward Dmytryk’s The Caine Mutiny (both films were among the five highest grossing movies of 1954) or Casablanca (released in 1942, and which Curtiz also directed). It opens in war-torn Italy on Christmas Eve, 1944. Bing Crosby plays Captain Bob Wallace, a famous nightclub entertainer who evidently didn’t use his wealth and clout to escape active duty. Danny Kaye plays Private Phil Davis, an amateur entertainer eager for the kind of career that Bob Wallace left behind. Dean Jagger plays General Tom Waverly, a career military man who is being relieved of his command, presumably because of an injury that now requires him to walk with the aid of a cane.

When we first meet this trio, Wallace and Davis are putting on a show for their tired and wounded comrades. Unwisely, they are staging this conspicuous gathering in a heavily contested combat zone. Towards the end of the performance, General Waverly slips into the makeshift theater and listens to Wallace sing Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas” (all the songs in the movie were written by Berlin). Soon, however, the war intrudes on what Wallace calls “this little Yuletide clambake.” Enemy planes begin dropping bombs on the area and the men all rush for safety. Davis suffers a minor arm injury when he saves Wallace from being crushed by a collapsing wall.

Just about everything in this opening scene echoes across the rest of the film, long after the war is over and Wallace and Davis have become a huge nightclub act in the manner of the real-life duo of Jerry Lewis and Dean Martin. The General will remain a highly respected but somewhat pitiful figure, a man who lost his mojo when he lost his command. Davis will forever use the arm injury he suffered saving Wallace’s life to try to bend Wallace to his will. Both Wallace and Davis will refer frequently to their military experiences.

When these lifelong bachelors finally meet two women with whom they decide they’d like to settle down, the women turn out to be the sisters of an old army buddy named Benny Haines (“The Dog-Faced Boy”). When the two entertainers are publicizing a show they have decided to stage for the General’s benefit, they contact an old army buddy who now has a network TV variety hour similar to the old Ed Sullivan Show (and somewhat unimaginatively titled The Ed Harrison Show). And in the film’s grand finale (which intentionally mimics the opening scene), Wallace, Davis, Waverly, and all of their surviving military comrades reunite in a Vermont inn, ostensibly to celebrate General Waverly, but actually just to revel in one another’s company again.

Just as most American war films of the 1940s and 1950s were triumphalist celebrations of U.S. military successes, White Christmas is a triumphalist celebration of postwar civilian successes. The film doesn’t explore PTSD (or “shellshock,” as it was called back then), or the difficulties facing minority veterans in the workplace. The men in White Christmas walk with the swagger of military victors. We learn very little about the men with whom Wallace and Davis served during the war, but most of them appear to have become prosperous and powerful enough to arrange a Christmas eve vacation to Vermont on practically no notice at all. When we see them at the end of the film, they are all (with one comic exception) fit, middle-aged white guys with attractive and well-dressed wives. It’s easy to imagine them as corporate chieftains or Madison Avenue admen.

The only ex-soldier in the film who hasn’t thrived in civilian life is General Waverly. Of course, even the film’s portrait of “failure” is rose-tinted. Waverly is now the owner of an enchanting bed-and-breakfast in Pinetree, VT. His is a life that millions of contemporary Americans would gladly trade up (or even down) for. Apparently a widower, the General lives at the inn with a doting teenage granddaughter and a wisecracking housekeeper who treats him with the casual intimacy of a wife in a TV sitcom. The General’s only true failing, we’re led to understand, is his inability to control the weather. It hasn’t snowed since Thanksgiving, so the ski trade upon which his lodge depends is down sharply, causing him to consider closing the inn and returning to active duty.

To help draw a crowd, Wallace and Davis improbably arrange to bring their big Broadway song-and-dance extravaganza (Steppin’ Out) to the inn. Even more improbably, they manage to fit Benny Haines’s two sisters, whom they have just met, seamlessly into leading roles in the show. More improbably still, they manage to announce their plans on a national television show without the General finding out, despite the fact that the program is the General’s favorite. Most improbably of all, nearly every member of the General’s old division is able to make it to Vermont at the drop of a hat.

These contrivances are not just formulaic sentimentality, they are part of the film’s celebration of America’s solidarity and can-do spirit. The point is that these men (Wallace, Davis, Waverly, and all the ex-soldiers they served with) defeated the Nazis and the Japanese Imperial Army and Navy and helped to make the world safe for Democracy again. Wallace and Davis’s status as military veterans isn’t incidental to their characters—it pretty much defines them, just as, for better or worse, it continues to define the General long after he has left the service.

Although Susan Waverly, the General’s granddaughter, seems fond of her grandfather throughout the film, it is not until she sees him in his military uniform for the first time near the end of the film that her eyes light up with an admiration that is nearly rapturous. And the General does indeed look great in his uniform—taller, straighter, more dignified than he ever looked in his civvies. Shortly thereafter, we see Wallace and Davis in uniform again too. But this time they are dressed not in combat fatigues (which would be a violation of service regulations since the men are no longer on active duty) but in the Class A green service uniforms that servicemen wore on formal occasions from 1954 to 2015.

At this point, even the Haines Sisters are dressed in the same way, although they never served in the military. These are the penultimate costumes the four principals wear in the film. After that, they are seen only in Santa costumes, suggesting that the only thing better than a man (or woman) in uniform is a mythical superstar. The show-within-the-show features musical numbers such as “Gee, I Wish I Was Back In The Army,” “The Old Man,” and “What Can You Do With a General?” all of which celebrate the participants’ shared military experience. Wallace and Davis’s connections to the General, to Ed Harrison, and to the Haines sisters all came about because of their military service. Even their connection to each other, the strongest relationship in the film, is directly linked to the army. Everything about White Christmas celebrates military service.

Later films such as Coming Home and The Deer Hunter (both of which were released in 1978 and both of which are about the damaged lives of men who served in Vietnam), would explore the devastating effects of combat on returning soldiers and their families and communities. Even in the 1940s and 1950s, Hollywood occasionally depicted the difficulties faced by ex-soldiers trying to readjust to civilian life in films such as William Wyler’s Best Picture winner The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) and Vincente Minnelli’s Some Came Running (1958).

White Christmas is the flipside of those films. It essentially serves as a sequel to all the films released in the 1940s about Americans in combat during World War II. If you want to know what happened to all those plucky boys who fought and managed to survive it all, White Christmas is your hopelessly optimistic answer. They toughed it out, came home, married their sweethearts, sired heirs, took their rightful places in the upper echelons of show business, the hospitality business, and other fields of endeavor, and lived relatively happily ever after. None of them had to deal with alcoholism, divorce, despair, or loneliness.

But is White Christmas’s triumphalism really less authentic than the harrowing experiences depicted in Coming Home and The Deer Hunter? Its portrait of combat veterans thriving after returning to civilian life is not, after all, entirely Hollywood hogwash. 16 million Americans served in the military during World War II, and millions of those Americans came home to build hugely successful personal and professional lives. I was born in 1958, and I grew up in a country run by the veterans of World War II and the Korean conflict. Everywhere I looked I saw successful ex-servicemen triumphing in civilian life.

Among the favorite film stars of my youth were numerous men who had served in WWII. Charlton Heston flew B-25 combat missions over the Kiril Islands in northern Japan. He was later injured on an Aleutian Island while attempting to rescue the pilots from a crashed military plane (ironically, he was run over by an ambulance). Paul Newman served on an aircraft carrier as a turret gunner in a warplane. James Stewart, Henry Fonda, Rock Hudson, Charles Bronson, Jackie Coogan, Tony Curtis—you couldn’t turn on a television or sit in a movie audience without seeing men who had served in combat in World War II and returned to find success in civilian life.

When I watched the Dallas Cowboys play football on television, the commentators would repeatedly remind their viewers that the team’s legendary head coach, Tom Landry, had served as the co-pilot on a B-17 Flying Fortress warplane and flown 30 bombing missions over Germany during WWII. He even survived a crash landing in Belgium after his plane ran out of fuel (his older brother, Robert, died in a similar incident). Byron “Whizzer” White, who served on the Supreme Court of the United States for most of my youth (having been placed there by WWII veteran John F. Kennedy), played for the Pittsburgh Steelers during the 1939 NFL season and led the league in rushing. A few years later he was serving with the U.S. Navy in the Pacific theater of WWII, where he would win two Bronze Stars for his heroism.

Even Senator George McGovern, the anti-war Democratic nominee for president in 1972, was part of an aircrew that flew 35 bombing missions over enemy territory in Italy during WWII. These were not quick raids but rather grueling eight- and nine-hour flights over heavily armed territories that often left his plane riddled with bullet holes. Titans of business, titans of science, titans of literature—during my youth, former WWII combat soldiers could be found succeeding in all walks of life, and White Christmas is an unapologetic celebration of that fact. Military service was a nearly universal experience for the men of the Greatest Generation, so it doesn’t seem odd that the Broadway stars and TV hosts and New England business owners of White Christmas all have a service background.

It is difficult to imagine White Christmas being remade and set in contemporary America. Our all-volunteer Army no longer equally represents every socio-economic stratum of American society. Not many contemporary showbiz stars, Silicon Valley CEOs, or even Washington politicians have seen combat. Few, indeed, have any military experience at all. The next time you feel like denigrating mid-twentieth century America for its racism, its homophobia, or its sexism, spare a moment’s appreciation as well. Those Americans fought to save you and your families from a future that might have looked like an episode of the counterfactual series, The Man in the High Castle.

Viewed as a romantic comedy, a bromance, or a musical, White Christmas may seem like just a lightweight piece of Hollywood fluff. But considered as a hymn to post-war America, it acquires additional depth. Today, it’s fashionable to view the U.S. military as nothing more than a big, clumsy blunderbuss of a bureaucracy, better at stumbling into wars than at winning them. Even the current President of the United States seems to feel that way. But the people who made White Christmas understood that all the bucolic villages and Broadway shows and corny TV programs and thriving business partnerships and Christmas pageants and millions of other worthwhile things that make America a great place to live, wouldn’t be possible without people who are willing to put on a uniform and go out and protect the country from its enemies.

Watch it alongside William A. Wellman’s 1945 film The Story of G.I. Joe, which depicts the Battle of Monte Cassino, an event that produced more American casualties than any other battle in the European theater of operations except for the Battle of the Bulge. It stars Burgess Meredith as war correspondent Ernie Pyle, a real Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter who was actually there. Here’s how Wikipedia describes the Monte Cassino sequence:

The company advances to a position in front of Monte Cassino, but, unable to advance, they are soon reduced to a life of living in caves dug in the ground, enduring persistent rain and mud, conducting endless patrols and subjected to savage artillery barrages. When his men are forced to eat cold rations for Christmas dinner, Lt. Bill Walker [Robert Mitchum] obtains turkey and cranberry sauce for them from a rear echelon supply lieutenant at gunpoint. Casualties are heavy: young replacements are quickly killed before they can learn the tricks of survival in combat.

Near the end of White Christmas, surrounded by his old army buddies at the General’s Vermont inn, Bob Wallace tells them to look sharp like they did back at Monte Cassino. It’s the only battle of the war specifically mentioned during the film. Watching the two films back-to-back will give you a cinematic view of both the highs and lows experienced by some of the men of the Greatest Generation. Unfortunately, Ernie Pyle never got to see The Story of G.I. Joe. It was released on June 18, 1945, but he had been killed two months earlier during the Battle of Okinawa. If the ex-soldiers of White Christmas seem to be enjoying life a little more than they should, maybe it’s because they felt they had to make up for the enjoyment their fallen comrades would never experience.