Top Stories

Fearful Norwegians Wonder: Are 'Swedish Conditions' Coming to the Streets of Oslo?

Immigrants from certain backgrounds—particularly Palestinians, Iraqis and Afghanis—were many times more likely to commit violent crimes than other Norwegians

Oslo is an unremarkable place compared to other European capitals, lacking the picturesque charm of smaller Norwegian cities such as Bergen, Trondheim and Stavanger. But it’s pleasant and pretty enough. Tourists find it easy to get around, with lots to explore. The Oslo Opera House, which opened in 2008, is spectacular. And in summer, you can swim in the Oslofjord and enjoy expensive utepils (“outside beer”) on the seafront or on Karl Johans gate, the city’s broad main street. Like the rest of Norway, Oslo traditionally has been a safe place, even by the standards of other wealthy countries. It’s also remained more demographically homogenous than most of its neighbours, being geographically isolated from migration patterns that have affected the rest of Europe.

Over the last month, however, Oslo’s city centre has witnessed an eruption of unprovoked attacks on random victims—most of them ethnic Norwegian men—by what police have described as youth gangs, each consisting of five to 10 young immigrants. The attacks typically take place on weekends. On Saturday, October 19, as many as 20 such attacks were recorded, with victims suffered varying degrees of injuries.

One of the incidents involved a group of young men, originally from the Middle East, detained for attacking a man in his twenties in the affluent west end. According to police, the victim had been kicked repeatedly in the head while lying on the ground, in what appeared to be a random, unprovoked beating. Another victim that weekend was the uncle of Justice Minister Jøran Kallmyr, who suffered several broken ribs after being mobbed at the Romsås subway station.

The following weekend in Oslo, Kurds and Turks clashed over recent developments in Turkey, and ended up looting a branch of the Body Shop on Karl Johan gate, as well as destroying several cars. Car fires also have been on the rise, though the problem has been around for years. (Even in 2013, cars were set alight in Oslo at the rate of about one per week, mostly in the city’s poorer east end.) Overall, crime rates are still low by the standards of other cities, but the recent rise in youth crime suggests that may be changing. “We see more blind violence where people are attacked, ambushed and beaten up,” said Labour Party politician Jan Bøhler to the media last month. “This is terrorising our community.” While such observations are widely shared, Bøhler is notable for being one of the few politicians on the left who’s raised his voice about rising crime among young immigrants.

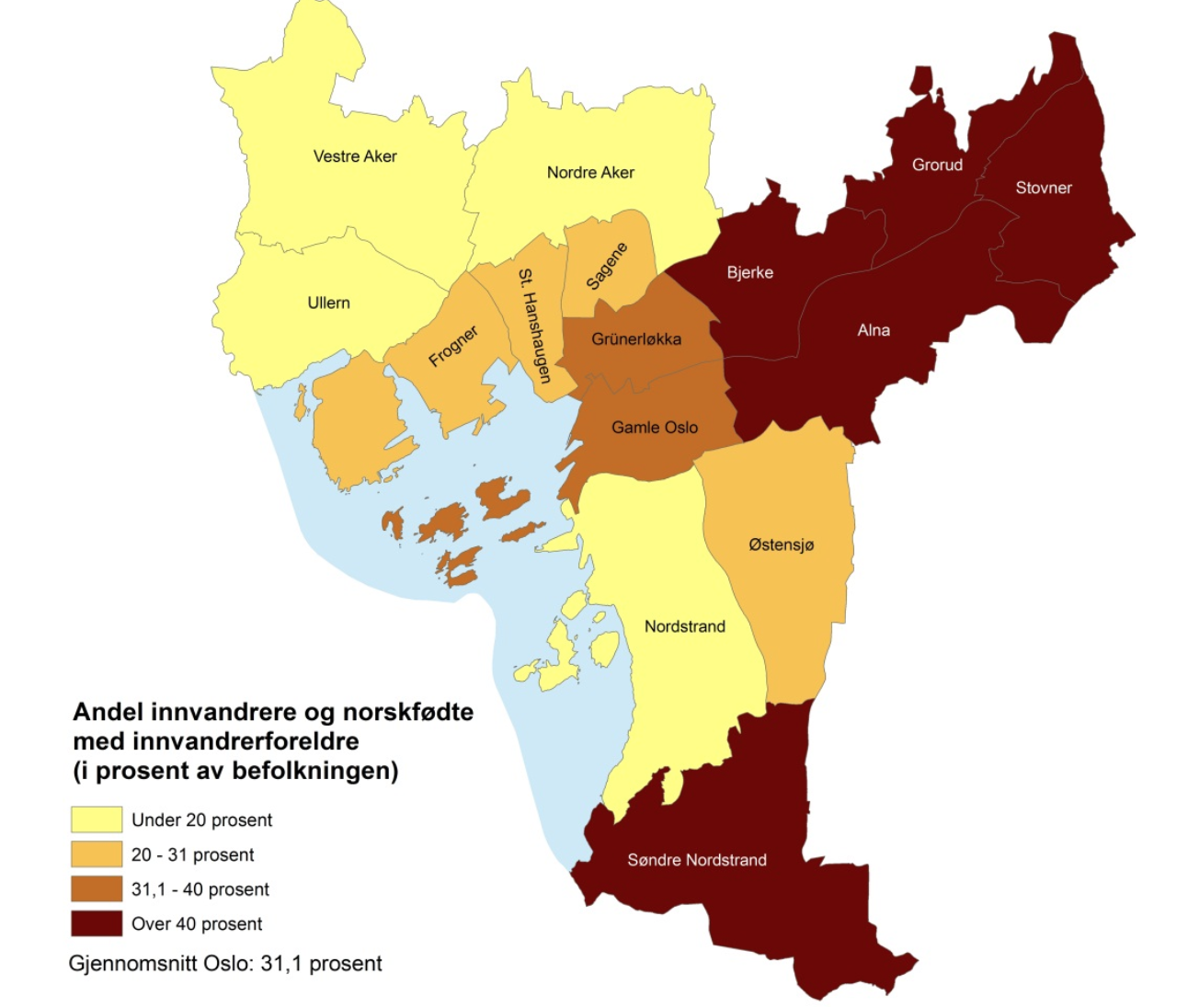

Oslo is the fastest growing capital city in Europe, despite the fact the country now is registering fewer births than at any time since the government started keeping track in the 19th century. About 14% of the country’s population is now composed of immigrants, with Poles, Lithuanians and Swedes topping the European migration sources; and Somalian, Pakistan, Iraq and Syria supplying the greatest number of non-OECD arrivals. Many of the immigrants congregate in Oslo, where, according to Statistics Norway, about a third of all residents are immigrants or born to immigrants. (As recently as 2004, the figure was just 22%.) In several areas, such as Stovner, Alna and Søndre Nordstrand, the figure is over 50%.

According to a 2015 Statistics Norway report, “most persons with an immigrant background living in Oslo come from Pakistan (22,000), while 13-14,000 are from Poland, Sweden and Somalia. There are large differences between the districts: Persons with a background from Pakistan and Sri Lanka are most represented in [the far eastern suburbs of] Oslo.” By one 2012 estimate, 70 percent of Oslo’s first- and second-generation immigrants will have roots outside Europe by 2040, and about half of the city’s residents will be immigrants.

Until now, Norway had seemed to cope well with the influx of immigrants from war-torn Muslim countries, in part because the intake levels generally were kept at a level that permitted newcomers to be integrated without overwhelming local resources. Indeed, there has been a broad consensus in Norwegian politics to keep immigration rates lower than those of comparable countries such as Sweden and Germany. Nevertheless, concerns have been rising in recent years, even if the ruling class was hesitant to discuss the issue. The country’s libertarian Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) has repeatedly asked the country’s statistical agency to report on the statistical relationship between crime and country of origin. In the past, Statistics Norway refused, saying that such a task was “beyond its capacity.”

But this year, for the first time, such a report was published. And the numbers were clear: Immigrants from certain backgrounds—particularly Palestinians, Iraqis and Afghanis—were many times more likely to commit violent crimes than other Norwegians (including other immigrant groups). In 65 out of 80 crime categories, non-Norwegians were over-represented. The largest discrepancy was in regard to domestic violence: Immigrants from non-Western countries were found to be eight times more likely to be charged for such crimes. Rape and murder were also heavily skewed toward these immigrant groups. Worryingly, the figures showed that second-generation immigrants were more likely to be criminals than their parents.

For a long time, the expression svenske tilstander—“Swedish conditions”—has been used to describe large Swedish cities such as Malmö, Gothenburg and Stockholm, which feature areas plagued by bombings, gang-related gun violence, robbery and rape. In the past, Norwegians used the expression somewhat disparagingly, insisting that such issues would never arise in Norway (while also suggesting that the situation in Sweden was itself exaggerated by those with an anti-immigration agenda). But gradually, “Swedish conditions” have seemed less distant.

Heidi Vibeke Pedersen, a Labour politician representing the immigrant-heavy area of Holmlia, recently wrote a Facebook post about her own experience, which was subsequently reprinted in VG, Norway’s biggest tabloid, under the headline “We have a problem in Oslo”:

Yesterday, my 15-year-old daughter went past [the suburb of] Bøler on a bus half an hour before another 15-year-old was robbed and beaten. Now I need to make a risk assessment: Is it too dangerous for her to go alone to the youth club…Young people now grow up in an environment where threats and violence are common, where adults might be afraid to interfere, and where they are told that the police are racist…Our part of the city is becoming more and more divided. We have areas that are mainly “Norwegian-Norwegian,” and others that have large immigrant populations. This isn’t diversity.

Pedersen’s article alluded to the fact that, in the quest to maintain their own cultures, some Muslims in Norway prefer to segregate instead of integrate. The newspaper Aftenposten recently uncovered the existence of Islamic schools presenting as cultural centres. And Islamsk Råd, the Islamic Council of Norway, now has proposed a separate branch of the Barnevernet—the government-run social services responsible for children—to deal with Muslim children.

The article was shared by many. But Pedersen’s use of such terms as “Norwegian-Norwegian” (or norsk-norske) didn’t sit well with progressives and community advocates. Hasti Hamidi, a writer and Socialist Party politician, and Umar Ashraf, a Holmlia resident, wrote in VG that Pedersen’s use of the term “must mean that the author’s understanding of Norwegian-ness is synonymous with white skin.”

Camara Lundestad Joof, a well known anti-racist activist and writer at the Dagbladet newspaper, accused Pedersen of branding local teenagers as terrorists. Using her own hard-done-by brother as an example, she explained how, in her opinion, Norwegian society has failed non-white young people. Had he been treated better, she argues, he and others like him would fare better. (One problem with this argument is that Norway is one of the least racist countries in the world.)

Of course, this tension between racial sensitivity and blunt talk on crime has existed for generations in many Western societies. But it’s a relatively new topic in Norway, which is only now embracing certain hyper-progressive academic trends. (Oslo Metropolitan University, for instance, has recently produced an expert in so-called Whiteness Studies.)

In fact, some influential Norwegians apparently would prefer that Statistics Norway had never released its report on crime and immigration in the first place. This includes Oslo’s vice mayor, Kamzy Gunaratnam, who told Dagbladet, “Damn, I’m angry! I’m not interested in these numbers…We don’t have a need to set people up against each other. These are our children, our people.”

But burying the truth is never a good long-term strategy for anyone, including members of immigrant communities. The more persuasive view is that these issues should be addressed candidly, while they are still manageable. Unlike many other European countries, Norway doesn’t yet have an influential far-right party. But that may change if voters see that mainstream politicians are too polite to address a problem that ordinary people all over Oslo are talking about.